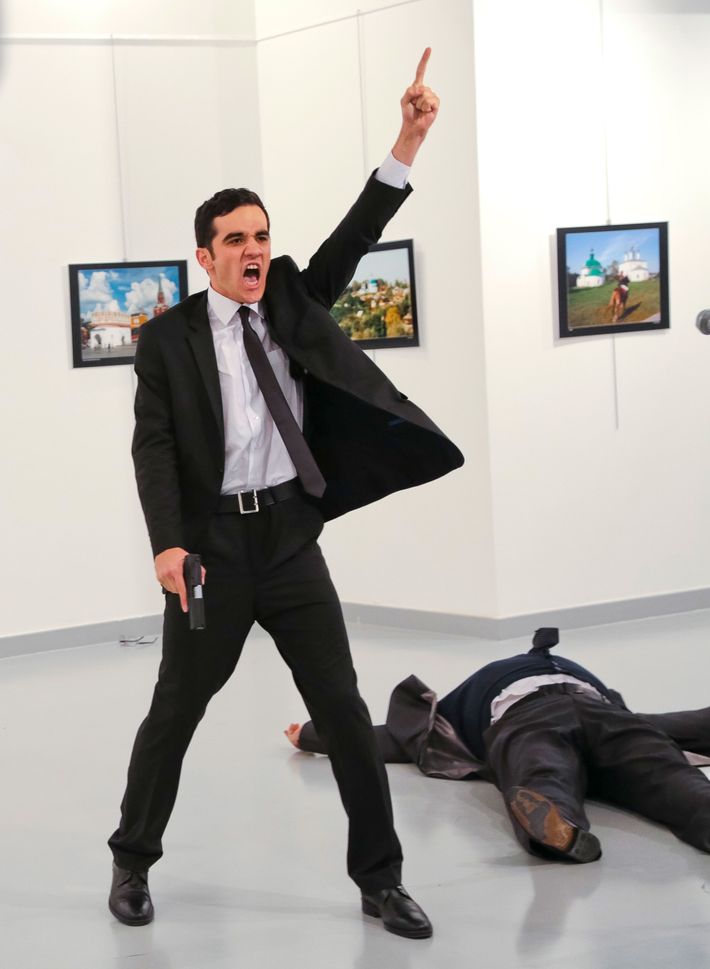

IÔÇÖve never seen anything like the photographs by Burhan Ozbilici* of the assassination of the Russian ambassador at an art gallery in Ankara, Turkey. A pathological act of bloodletting, terrorism, nationalism, a state of political siege. But in the stark white, pristine setting of an upscale art gallery showing contemporary art, with patrons, assassin, and victim all dressed in elegant black, the photographs themselves look strikingly surreal ÔÇö uncanny, even ÔÇö and, in some very painful ways, beautiful.

What makes these pictures so different from all of the other pictures of death that we see? The poses are almost classical, frozen, or rehearsed as if from theater, ballet, painting, or mannequin display. The photographer, working the art opening for the Associated Press, deserves all of the enormous credit heÔÇÖs received for responding as fluidly as a war photographer to the sudden outbreak of violence. But if I told you the images were fake, or staged, you might believe me. As Kurt Andersen put it on Twitter, ÔÇ£the great photojournalism of 2016 is continuing to resemble stills from a scary, not-entirely-realistic movieÔÇØ ÔÇö and that strange familiarity we feel in looking at the images is one reason they are so uncomfortable to contemplate. Everything in the images is emotion articulated, caught, performed, and real. All of this triggers an unreal internal visual dance. ItÔÇÖs a new surrealism of modern life, made all the more harrowing because it could not be more truly real.

The most instantly iconic picture is the assassin standing, brandishing a gun, gesturing, pointing a finger overhead, admonishing onlookers with the corpse sprawled and dramatically foreshortened behind him. The scene could be a modern-day martyrdom by the most theatrical painter of them all, Caravaggio; the prelude to DavidÔÇÖs Oath of the Horatii; or one of Robert LongoÔÇÖs large black-and-white Falling Men drawings of figures in dramatic arrested motion ÔÇö human beings seemingly cut out from the world, thrust onto this pictorial stage.

In this image, frozen perpetual motion ÔÇö an entire scene of action and worldview is caught in an instant. Notice the picture is in perfect focus. This is not the shaky, out-of-focus, ill-framed onlooker iPhone shot of assassinations and revolutions past.┬áOzbilici is obviously a pro, there on assignment ÔÇö in a dark irony, on assignment to cover an art party. And the setting is surely an element of the imageÔÇÖs strangeness ÔÇö again, it feels both quotidian and ÔÇ£staged.ÔÇØ The gallery lighting balances and color-corrects everything, theatricalizes it all the more, making the action that much more striking. Look close and notice the key factor: This picture is taken from eye level. The photographer isnÔÇÖt running away, hiding, in another room or in a crouch. Whether cravenly or by instinct, the photographer immediately reacted, moved into the action from almost straight on and framed the picture perfectly. He or she values frontality, clarity, structure, density, form. This is far from an accidental image. This is a radically self-determined picture, instantly polemical, powerfully formal.

The picture of the group of onlookers huddled in a corner is taken from close-up. Although it was still captured from a standing position, the┬áOzbilici appears to have stooped over these people to take the picture. None of them take notice of him. The photographer, in spite of being absolutely present, is simultaneously not there. (Even the assassin didnÔÇÖt look at him.)

This group picture is neatly cropped. As in great paintings of differing individual dramatic reactions in crowds, this photo is an encyclopedia of reactions. The weeping woman on the left is held by a man; notice she looks into herself more than at the room, at the agony within her. He is on one knee, ready to move. But he keeps an eye on the still-unfolding action in front of him. He gives the picture its eternal now (this is helped by the still-rolled-up magazine he holds). Next to him is a crouching man who comes almost directly from academic figure-drawing classes. His profile is strong, his pose stable, all in black (as with central figures, his head obscures the identity of two women behind him). A couple comes next. Or what looks like it. SheÔÇÖs on the floor with her knees up and her purse poised on her skirt. Her eyes are attentive but still turned inward. Finally, what passes as the old wisdom figure in this picture. Maybe heÔÇÖs Jewish. HeÔÇÖs older, with a bush of curly, thinning hair, looking on forlornly, knowingly, like heÔÇÖs aware that this is history happening beyond his control. Half outside the frame is a woman in blue. The only person getting out of the picture is in color, entering another existence. Looking at her, we are stuck in this configuration ÔÇö looking for, but unable to find, a way out.

* This column has been updated to include the name of the photographer responsible for these remarkable photos. The original version was written in a rush, and we regret having neglected to properly credit him for his great work.