Each month, Boris Kachka offers nonfiction and fiction book recommendations. You should read as many of them as possible.

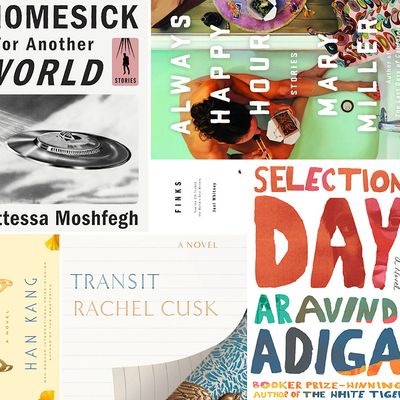

History of Wolves, by Emily Fridlund (Atlantic Monthly, Jan. 3)

Imagine one of those twisty ÔÇ£GirlÔÇØ-titled mysteries in the hands of a great stylist. FridlundÔÇÖs debut is something like that, but better. The young novelist evokes the creaks and shivers of a Minnesota winter as expertly as she plumbs the mind-wanderings of a teenage daughter of failed commune-dwellers. Linda ÔÇö whose older self narrates the story ÔÇö ends up babysitting for a new family across the lake. Then her teacher is accused of sex with a student, a young boy dies, mysteries multiply, and prose and plot braid together into an indelible story of fascination and dread.

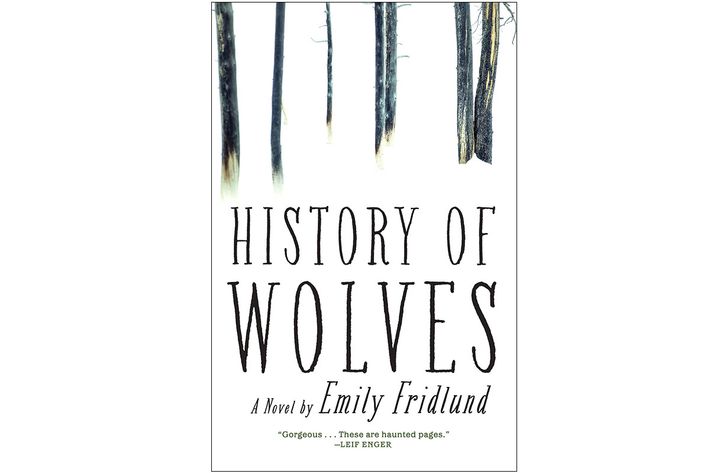

Selection Day, by Aravind Adiga (Scribner, Jan. 3)

In his third novel, the Booker Prize winner (for The White Tiger) continues to tackle his central project ÔÇö analyzing and satirizing IndiaÔÇÖs socioeconomic growing pains ÔÇö this time through the prism of the nationÔÇÖs postcolonial pastime. Two brothers excel at cricket under the domineering coaching of their father, a sort of Williams dad gone mad, and serve a sport that offers class uplift but also exploitation and corruption. Manju, supposedly the lesser of the cricket-star brothers, undergoes a crisis of sexual confusion involving their greatest rival, and suddenly all the bookmakersÔÇÖ bets are off.

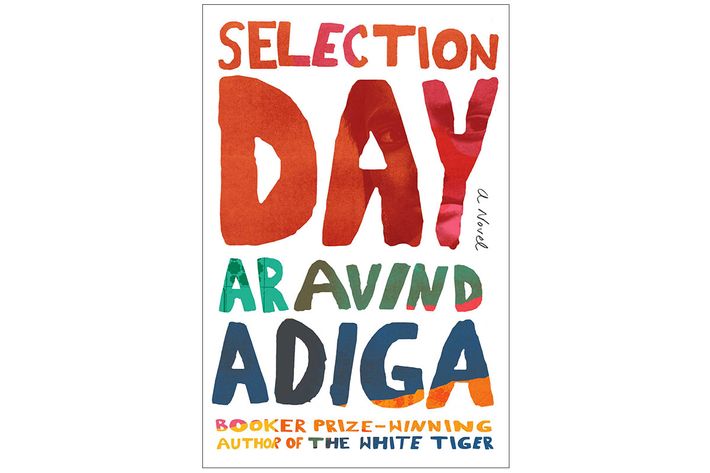

Always Happy Hour, by Mary Miller (Liveright, Jan. 10)

Somewhere between the old trope of the fallen woman and the unctuousness of the likable heroine, the young narrators of MillerÔÇÖs searching stories inhabit the middle space known as reality. They drink, bed the wrong men (or the right men at the wrong times), and puzzle over peers who seem to have figured life out. Anyone whoÔÇÖs faltered on the way to success and contentment might find solace in the do-gooder in ÔÇ£Big Bad Love,ÔÇØ or the boozy, boyfriend-enabled composition teacher in the title story.

Finks: How the CIA Tricked the WorldÔÇÖs Best Writers, by Joel Whitney (OR Books, Jan. 10)

The story of the agencyÔÇÖs infiltration of AmericaÔÇÖs cultural institutions (especially The Paris Review) has been told before, but not this thoroughly or colorfully ÔÇö thanks to WhitneyÔÇÖs reporting as well as the wit of his subjects, who knew how to write a letter. He shreds the idea that spooks like Peter Matthiessen worked only for the ÔÇ£good CIA,ÔÇØ but doesnÔÇÖt limit himself to PlimptonÔÇÖs dashing crew. The governmentÔÇÖs entanglement with the Latin American masters (ranging from negative propaganda to subtle exploitation) gets a full airing that enlarges the story of the (first?) Cold War.

Human Acts, by Han Kang, trans. Deborah Smith (Hogarth, Jan. 17)

KangÔÇÖs last novel, The Vegetarian, a best-seller in South Korea and a winner of the Man Booker International Prize, made a grotesque social parable out of a womanÔÇÖs sudden change of diet. Her new book depicts the fallout of a genuine atrocity ÔÇö the massacre and torture of dissidents under the countryÔÇÖs 1980s dictatorship ÔÇö with more devastating results. The long wake of the killings plays out across the testimonies of survivors as well as the dead, in scenarios both gorily real and beautifully surreal, until Kang herself intervenes to explain the personal provenance of her political fiction.

4 3 2 1, by Paul Auster (Henry Holt, Jan. 31)

Compared to Auster at his most twistingly metafictional, his first novel in seven years is deceptively simple. Archibald Isaac Ferguson is born in 1947 (exactly a month after Auster was), whereupon he splits into four different people with wildly divergent futures ÔÇö though all four Fergusons court the same woman, and all are locked in the prison of one manÔÇÖs DNA. AusterÔÇÖs trippy idea becomes, over 800-plus pages, a feat of epic realism, grounded, like Kate AtkinsonÔÇÖs similarly fragmented Life After Life, in history, psychology, and very good writing.

Transit, by Rachel Cusk (Jan. 17)

CuskÔÇÖs innovative novel, Outline, now has a sequel, and Ferrante, Knausgaard, and other avatars of semi-autofiction have a successor. Her barely described narrator, Faye, a divorced writer in the midst of a disastrous home renovation, somewhat resembles Cusk, whoÔÇÖs written (controversially) about her own family troubles. But Faye is also a vessel for other stories ÔÇö told by an ex-boyfriend, a son, a builder, a hairdresser ÔÇö that interrupt and occlude her own narrative. ItÔÇÖs a bit of a formal experiment, but Cusk is a magnetic teller of nested tales, and always leaves you wanting more.

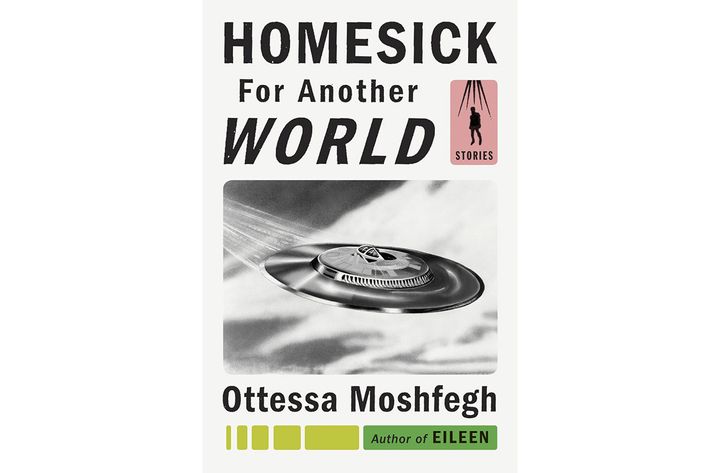

Homesick for Another World, by Ottessa Moshfegh (Penguin Press, Jan. 17)

LetÔÇÖs reclaim the word ÔÇ£unflinchingÔÇØ from the marketers and apply it properly, as to the 14 stories in this follow-up and spiritual sequel to MoshfeghÔÇÖs unsettling debut novel, Eileen. Her protagonists are, as often as not, loners and creeps, and dropping in on their addictions, bad marriages, and self-degrading compulsions might leave you feeling a little creepy too. But the cumulative effect is to open up the world ÔÇö theirs and ours ÔÇö to empathy for the less perfect (and perhaps more interesting) among us.