One summer, when Brit Marling was a kid at camp in Wisconsin, she told ghost stories late at night to the girls in her cabin. At first, everybody loved this. But after a few nights, something changed. “I think things were just percolating in everybody’s imaginations,” says Marling. The camp called her parents and said they had to pick her up; her ghost stories were freaking people out. Clearly the form of her stories (bunk-bed broadcast) didn’t match up with the content (Marling’s uncanny conjurings).

Until recently, a variation of this problem marked Marling’s career. As a screenwriter and actor, she’s created several widely praised but little-seen indie films, such as 2011’s Another Earth and 2013’s The East. Then, with almost zero fanfare just before Christmas, Netflix released The OA, an eight-part series starring Marling that she co-wrote with director and creative partner Zal Batmanglij. This zigzagging tale of a traumatized survivor of a near-death experience and a mysterious abduction quickly became the latest riddle-me-this series to cause an online frenzy. An unreliable narrator and episodes of varying length add up to something that’s not quite episodic TV and not quite film; Marling equates it to a novel, considering it a new form for a new kind of TV. “The OA couldn’t have existed three years ago,” she says.

This isn’t just because streaming services like Netflix allow creators to slip the formal limitations of feature films and network series. Today’s mature “peak TV” audience, the Breaking Bad–Game of Thrones–Westworldgeneration, is eager for material that doesn’t just push boundaries — it shoves. “I would have thought [The OA] would be more of an outlier. It’s pretty far-out in its form,” says Marling. “But the audience seems very ready for that. They want to be surprised, and they want to feel new emotions that they can’t find names for.”

The OA follows Marling as Prairie Johnson, a formerly blind young woman who returns to her suburban home after seven lost years, her sight mysteriously restored, her story shaky. Every night, she sits fireside (metaphorically, next to votive candles) in an abandoned half-built house and unpacks what happened for an audience of four high-school boys and one solitary algebra teacher. In episodes that range from 30 minutes to over an hour, her whereabouts are explained as the story meanders through a maze with stops at Russian oligarchs, Room-like captivity, and — this is probably not happening on CBS — the transformative power of modern dance. At the end of the eight chapters, the viewer has to decide whether this has all been just the world-building of a psychotic mind — an exercise in PTSD healing — or a sincere plea for openness to a new metaphysical reality.

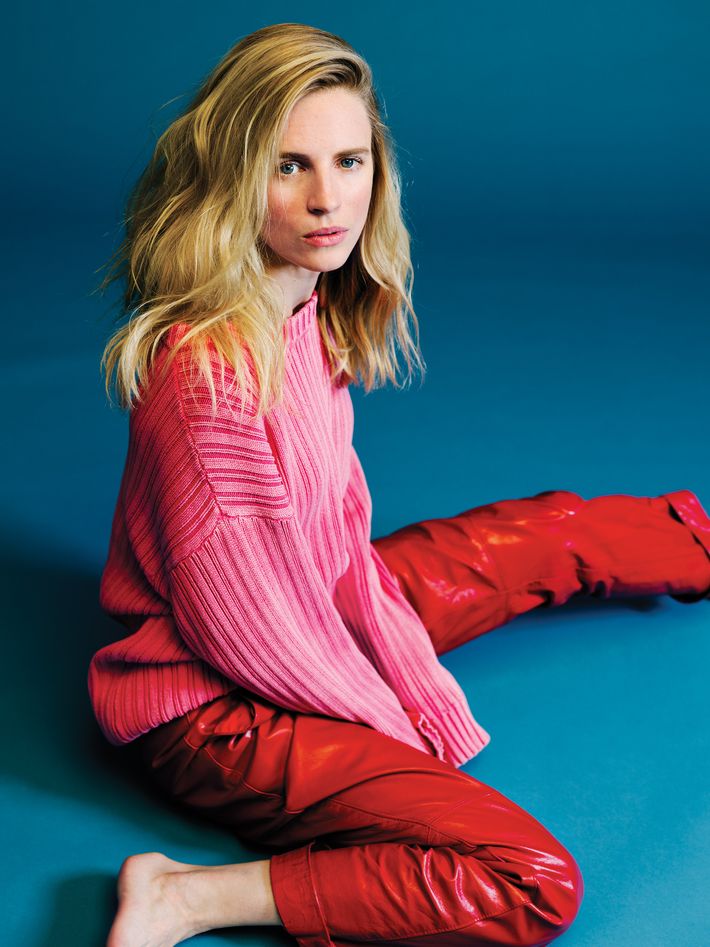

Being with Marling in person isn’t so different from being one of the neighbor kids whom Prairie enchants. (Perhaps it helps that we are also fireside, albeit in a Soho hotel, next to a purely decorative fireplace.) She is 33, warm and earnest, squinting as she carefully searches for words, her restless mind pinging from Russian fairy tales to Nick Cave to steady-state economics. It’s clear why The OA is so stuffed with ideas, all of which are now being eagerly dissected on internet threads with affection and incredulity. (“What on God’s green Earth is that purple liquid?”)

The form of The OA actually preceded its content; finding a container big enough to tell a story the way they wanted was the jumping-off point for Marling and Batmanglij. The two met at Georgetown 15 years ago after a student-film festival and have since collaborated on several projects, the beneficiaries of a climate in which it’s possible for young filmmakers to make small movies about provocative subjects, like 2012’s Sound of My Voice (in which Marling plays a cult leader) or The East (in which she’s a corporate spy infiltrating an anarchist collective). But these kinds of micro-budget movies have little chance of finding a sustaining audience against the marketing muscle of blockbuster superhero films. And anyway, Marling had begun to feel that features were old-fashioned, creatively constraining. “We just found ourselves struggling with a density problem in movies. By the time you get the world and all these people set up, you have a half-hour to play in it, then you’re out,” she says. “We started to think more about doing a mind-bender in a long format. We thought, What if you actually took the time to develop what’s at the center of the labyrinth, even if you never get there? We spent a year and a half just making all of this stuff up, doing the mathematics and the story. This first season is the outermost ring of that labyrinth.”

For months, she and Batmanglij would meet in the morning at one or the other’s L.A. home, building the story. They read up on near-death experiences, an obsession first sparked by an encounter at a party years ago that had stayed with Marling. In a crowded room, she noticed a stranger standing still, unperturbed by the surrounding social chaos: “She had a kind of radical autonomy and awareness.” The woman told her that she had died once, on a gurney in a hospital awaiting surgery, and that she had left her body and floated above, with a bird’s-eye POV of the hospital rooms and corridors. “She said she felt an interconnectivity,” recalls Marling. “The only thing she thought about was, Did I tell the people I love how much I love them?”

In The OA, the tribe of misfits that assemble each night — including a high-school bully and a trans boy — crave that kind of connection and love, and Prairie is the conduit. To make sense of their teen characters, Marling and Batmanglij spent time in midwestern high schools, sometimes leading filmmaking classes in exchange for interviews where they would record the kids’ gestures and speech patterns for study. The selfie-reared students were extremely comfortable in front of a camera but also confessed to a kind of alienation that Marling read as the darker side of their tech-saturated lives. “How do you come of age in a time where the entire catalogue of porn is at your fingertips? Or beheading videos. Stuff that you see that you cannot unsee,” she says. “It felt like there was a kind of floundering, like a rage, but also a deep intelligence and a hunger for something more, and wondering where they can get it from.”

Marling’s empathy for teenagers arises naturally: She grew up in Chicago and Orlando and remembers her young self as awkward, short and skinny with braces, her mind a whirlwind of ideas and energy that got her picked on. Still, she was able to enlist the neighborhood kids to appear in backyard plays she wrote, including a mash-up of Michael Jackson’s “Billie Jean” and A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Parents will pay anything to see their kids perform, Marling learned, and so she charged five bucks a head and earned some serious cash.

Her own parents were real-estate developers, and Marling used to play in unfinished houses, not unlike the one in The OA, performing characters and lives. In this affluent milieu, the expectations for young people were more limited than Marling’s imagination: lawyer, doctor, investment banker. Marling went to Georgetown to study economics because she loved math, hanging out in the library until 2 a.m. with fellow nerds, solving proofs.

In an email, Batmanglij recalls her as a strikingly calm teenager. “Somewhere along the first year I found out from someone that Brit was top of her class and I mean the top of her class,” he wrote. “But I still didn’t quite get it. It took me some more time to realize that Brit is a person who loves to learn. This is key in understanding Brit: the time and work and patience it takes to learn something from scratch do not scare her.”

At Georgetown, Marling grew disillusioned with the way her classes reinforced a status-quo worldview. “You learn that a lot of education in this country can be an indoctrination into a system that has failed and is failing us,” she says. An internship at Goldman Sachs showed her a life she didn’t want. “It’s like you take the blinders off the racehorse and the racehorse suddenly gets that the track is just a circle. You’re looking at the open pasture and you’re like, How do I get over there?”

It took a while. She moved to L.A. to act but found herself on the audition treadmill, in rooms with women who looked like her and across tables from men deciding their futures. This is what young actresses do, of course: wade through the swamp of starter roles, hoping something meaningful rises through the muck. Braces long gone, Marling has the sugar-spun looks to play many a girlfriend in an action movie (and she did play Richard Gere’s daughter in Arbitrage), but her constitution wasn’t up for it. “I might just be a little too porous,” she says. “I felt like, I’m not going to be able to get through the swamp, and if I do, by the time I get to the other side, I won’t be the person I thought I was, I’ll be somebody else.”

So to get the career she wanted, she started writing and traveling. She and Batmanglij fled L.A., literally riding the rails across the States. They took up with a group of “freegans,” Dumpster-divers who live off the grid. The experience anchored The East, but it also showed Marling a model for her art. “Something I really learned from people we spent time with on the road is, they just do. They don’t wait for permission. There’s an abandoned building next door to you — grow a rooftop garden. If you just begin doing and creating and keep practicing and practicing, eventually you reach a place where you’re telling a story that carries something across.”

The OA feels like that eventuality, a story whose themes of freedom and category-busting mirror Marling’s own career. She’s a new-model auteur in the vein of Sarah Polley or the Duplass brothers, artists who couldn’t get the nourishment they wanted in the mainstream and so stepped to the side and built their own thing. What’s surprising is that, in this moment of a new kind of TV, the mainstream seems to have risen to meet her, even though what she’s built is pretty far-out. When Prairie is abducted, she and her fellow captives plot their escape not by smashing through their Plexiglas cages but by transcending their bodies via five “movements” that can heal the sick and lead them to other realms of existence. An unscientific survey of online chatter seems to identify the movements as the point in the series — around episode five — where one kind of viewer gets excited to see something she’s never seen before and another declares it bonkers and flees. Online, Vulture broke down the movements in a handy how-to guide, giving names to each, like “The Fairy Fart” and “Human Tetris.”

Of course, this is a snide dig at modern dance — that elitist punch line— and Marling gets that the movements are discomfiting for some. “We hate the body in this country. We’re ashamed about our bodies,” she says. “And it is weird. You’re moving like this” — she does a movement, hands slashing — “you’re hissing. The first couple of times, of course, everybody laughs. The laughter comes from embarrassment, the embarrassment comes from fear, the fear comes from vanity. Then something totally remarkable happens. The moment you start moving, that shame really does fall away. It happened to all of us. The more we did the movements and practiced them, the more they became this other kind of language.”

It’s hard to imagine The OA existing as an elevator pitch, but Marling and Batmanglij successfully persuaded Brad Pitt’s Plan B to come onboard as producers early on, and then went out to the networks, shopping around the first chapter. While trying to sell it, they would stand up in the room, acting out the arc of the full eight hours, switching parts, hitting the big moments. “I think people felt: ‘I don’t know what this is exactly, but it seems like they’ve spent a lot of time on it,’ ” Marling says, laughing.

There were other offers, but Netflix was most in tune with their innovations; Marling says they got no pushback about the weird episode lengths, and no grief about breaking screenwriting rules by introducing main characters four hours into the story. “They were excited about the frontier of storytelling, like how can the form change now that we’ve been unfettered from marketing? What does internet-streaming storytelling mean?”

Marling and Batmanglij have already mapped out a second season of The OA, though it hasn’t officially been renewed. Or maybe it has: Production of the first season was shrouded in secrecy. There were no cast announcements, and signs to the set, just outside New York, were written in a code based on Braille. It was Netflix’s decision not to promote The OAin advance, unleashing it for the Christmas binge season with no publicity. Marling says she was okay with this strategy — which seems to have paid off — fiercely protecting the mystery she’d created from being prematurely unraveled.

Now that this strange series is in the world, she’s good with the digital scrutiny, watching happily as solving the mystery (which may be unsolvable) has become a kind of collective experience. The OA, on- and off-screen, seems to be connecting people, which is what Marling has always wanted from her art. “I think you kind of just have to put it out in the world, learn what you can learn, then shut down and go back in the cave and try to get better at telling a story again.”

*This article appears in the January 23, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.