It’s rainy and cold, and one of the actors on Legion is confused about whether he signed up to be on a superhero show. We’re in the home stretch of production on the first season of this FX drama, the much-anticipated new series from Fargo showrunner Noah Hawley. The actor is about to do another take of a scene in which a willowy telekinetic named David Haller executes a wild display of his psychic powers. The man (whose presence constitutes a significant spoiler, so we’ll stay mum on his identity) stands in the mud of a remote forest 40 miles from Vancouver and points at the chest of the actor playing David, the svelte and stubbled Englishman Dan Stevens. “Is that” — the man pauses and wiggles his index finger in the direction of a cryptic geometric shape on David’s T-shirt — “your superhero insignia?”

It’s a reasonable question, given that the show circles around the David Haller character, who has been wreaking havoc across the superhuman-redolent Marvel Comics universe for decades. But Legion is an odd duck. In an era where the global entertainment economy is fueled by a thick stream of barely distinguishable superhero movies and television, Hawley’s project feels blissfully unique.

Indeed, it forces you to ask what a superhero story would look like if you stripped away almost all of the superhero-y trappings. In Legion’s lushly shot cosmology, there are no capes or uniforms. Although David originated in X-Men comics, the show is narratively and tonally unconnected to the universe of the long-running X-Men film franchise. There are no laser blasts or secret identities. There isn’t even a consensus among the characters about what constitutes reality and whether the memories they recount for the audience ever actually happened. Instead of certainty and two-fisted narrative clarity, Legion presents a heap of broken images, a collection of arresting vignettes that lock the eye and ear but rarely explain themselves.

The shirt symbol is one such image. Stevens registers his co-performer’s question about it, then shrugs and changes the subject to the weather. Does that mean the answer is no? If it’s not an insignia, does it have some other significance? Could it just be something that the costume designer thought looked nifty? Does Stevens even know? The man points again, this time at a metal object wrapped around Stevens’s skull. “What is that thingon your head?” he asks. This time, Stevens gives some answers, but the man struggles to interpret them, narrowing his eyes and eventually just shaking his head in benighted resignation.

Viewers will find that they share the man’s bafflement when the show debuts February 8 — and that’s entirely by design. Indeed, Legion’s plot, setting, and genre are so ambiguous that they add up to something revolutionary: a superhero-comic adaptation that’s deeply, deliberately, and thrillingly challenging to watch. After conquering the multiplex, the networks, and the streaming outlets, superhero fiction has come to establish a beachhead in the land of prestige cable, where water-cooler dissection is prized over message-board frothing.

Hawley is leading that expedition and faces the exquisite challenge of getting fanboys to tolerate the slow confusion of novelistic prime-time dramas while also getting the Mad Men crowd to swallow superheroic tropes. But he isn’t that all that concerned about pandering to the snoots in the latter group. I ask him if he tries to avoid using the word superherowhile talking about Legion, for fear of alienating people; “No” is the professorial 50-year-old’s swift reply. “I don’t really care about that. The people who care about that stuff and aren’t going to come to the show? They’re the ones who are missing out. My feeling is there’s a lot of straight drama on television. My goal in life is to try to create something unexpected, and genre is the tool in doing that.”

The particular genre Hawley’s chosen to wield here is not one known for subtlety. The eight-decade-old superhero-comics canon is stuffed with blunt stories that proudly traffic in punches and zingers — and the filmic superhero boom that began at the turn of the millennium has followed suit. Megafranchises starring the Avengers, Batman, Spider-Man, and their spandex-clad ilk have become the financial pillars upon which much of the modern studio system is built, and they’ve done so in no small part by being as direct about storytelling as you can get. Superhero filmmaking is a populist art, committed to streamlined narratives, clear stakes, unambiguous visuals, and characters who say everything they’re thinking. You can get what’s going on in an Iron Man movie whether you’re 8 or 80, nerd or newbie, Bostonian or Beijinger.

Of course, there have been plenty of superhero comics that force the reader to dig for meaning, but even they rarely survive the translation to film unscathed — the best example is Zack Snyder’s 2009 adaptation of Watchmen, which blithely stripped the 1986 graphic novel of anything subversive or deconstructionist. A few recent Marvel projects on Netflix have aspired to be more than just beat-’em-ups: 2015’s Jessica Jonestackled rape and PTSD with startling frankness, and 2016’s Luke Cageriffed on Black Lives Matter and police brutality. But even those projects, admirable as they were, were only challenging in their social agendas, not their approach to filmmaking.

Legion, on the other hand, is a chore, and very deliberately so. When we meet David, he’s spent most of his life being treated for schizophrenia because he hears voices that may just be a manifestation of psychic abilities that we only see in brief, confounding flashbacks. His every waking moment is a chore, and Hawley wants to drag you down with him. “I was interested, after Fargo, which is very objective storytelling, in doing something subjective, in the sense of, here’s a character who either has schizophrenia or he has these abilities,” he says. “He’s a haunted house, and the things that he’s seeing, the things that he’s hearing, they might have a logical explanation, but he doesn’t know that.”

If there are logical explanations for what the hell’s happening in Legion, they certainly don’t appear in the handful of episodes released in advance to critics. If you squint, the plot is sort of coherent: David’s abilities manifest themselves disastrously while he’s in a mental institution, and he joins up with a ragtag group of fellow genetic abnormals, who enlist him in their struggle against shadowy government forces. But on a minute-by-minute basis, even that basic thread is hard to suss out, largely because it doesn’t happen in sequence. We jump back and forth in time, first in the form of staccato flashbacks tossed out in seemingly arbitrary order; then, bizarrely enough, in the form of journeys in which the characters physically enter those flashbacks and try to figure out what’s true or false about them. To make matters more head-scratching, the memories change every time we see them. David also switches bodies with a young woman named Syd Barrett (a reference that’s perhaps a little too on the nose), and it’s unclear whether certain things happened while David was David or while he was Syd. He sees monsters and apparitions — but are they real or just metaphorical?

Even the setting is pointedly ambiguous. “Noah wanted to make sure that the audience was as confused as David is about what is real by not having a time or a place, never saying where we are,” says production designer Michael Wylie. That meant sets and outfits that were unstuck in history. Some of the costuming and décor is, as Hawley puts it, “like a 1964 Terence Stamp movie,” all powder-blue wool coats and sleek wooden tables. Other times, there’s a kind of ’70s kitsch thing going on — vomit-orange tracksuits and garish white lamps abound. But then we’ll abruptly see Call of Duty–esque black-ops troops and tablet computers that make an iPad look like an abacus. There’s a city and a forest, but no place names; nothing feels pinned down. “It becomes more of a fable in a way,” Hawley says. “It’s a once-upon-a-time story.”

That kind of weirdness is something that the television medium — cheaper, narrower in distribution — enables in a way that global-market films can’t. “Every director puts their stamps on Captain America movies, but you don’t have the freedom that Noah did here, because I think those fans expect more of what was in the comics,” says Legion executive producer Lauren Shuler Donner, who has since the early ’90s been the shepherd of the X-Men film and TV rights that her bosses at Fox covet so dearly. Though Hawley is the one in the limelight for the show, Donner deserves much of the credit — she sought him out specifically and has been his chief enabler ever since. “I didn’t want to know any other writer that was available,” she says.

Hawley’s creative decisions have led to a product that is aesthetically subversive and visually overwhelming in a way that a Superman movie never could be. That’s appropriate, given that visual ambition is somewhat baked into the David Haller character. He sprung from the skulls of writer Chris Claremont and writer-artist Bill Sienkiewicz in 1985, during the peak of their run on an X-Men spin-off comic called The New Mutants. By that time, Claremont had been the premiere writer of X-Men tales for a decade, rescuing the angsty mutants from obscurity and developing a reputation for infusing his stories with an admirably earnest brand of liberal polemic.

Having already tackled racism, class conflict, and generation gaps, Claremont wanted to take aim at the Israeli-Palestinian quagmire. David Haller, oddly enough, was to be his vehicle. He was an Israeli mutant with psychic abilities including incorporating other people’s minds into his own, one of which was that of a Palestinian terrorist who had tried to murder him. “It was about focusing it all down and putting it in the most personal and visceral terms; not talking about country, but talking about a person,” Claremont recalls. “How do you strike a balance?” David’s nickname, Legion, was both a rad-sounding super-person moniker, but also a comment about the fact that he was more of a clattering mass of people than an individual.

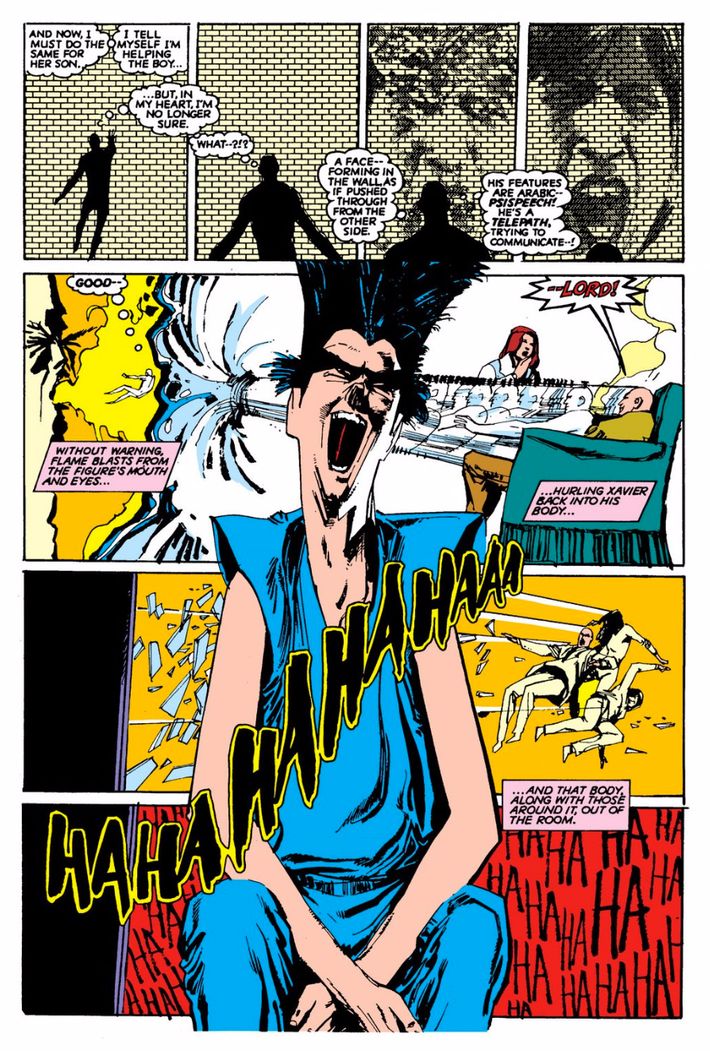

When David starts to go to war with his own personalities and wreaks havoc on the world, some X-Men back-benchers step in to stop him, and their leader, Charles Xavier — who discovers he’s David’s father — enters his brain, which is made manifest as a surreal landscape. Sienkiewicz was a trained painter, and Claremont gave him very little artistic direction. The artist wanted to starkly contrast David with the bald, well-groomed Xavier, so he went a little nuts and designed an adolescent with sackcloth clothing, a tremendous unibrow, and a towering pillar of black hair that would make Kid ’n Play blush.

Sienkiewicz was fascinated by the impetuous urgency of Egon Schiele’s self-portraiture, so he borrowed the Austrian expressionist’s wiry frame and shocking mane, as well as his love of disorienting backdrops. In David’s mindscapes, sense and perspective are thrown out of joint, and though Legion, the show, eschews virtually everything from its comics source material, Hawley wisely chose to preserve the notion of a brain that invites other folks inside it, only to subsequently spook the shit out of them.

The character subsequently fell into relative obscurity, only popping up every now and again for one apocalyptic battle or another, never quite acting as a villain but certainly living as a mentally unstable loose cannon. This obscurity ended up being quite beneficial for the character’s artistic fortunes, because Hawley likely wouldn’t have used him if David had been more popular. Both men are on the fringes of the X-Men franchise, and they’ve only been empowered thanks to a woman who wrote that franchise’s playbook, then decided it needed to be burnt to a crisp.

It’s appropriate that Donner and her X-Men intellectual property would be the catalysts for Legion’s great leap forward in the long-underwear genre, because she’s arguably the one who started the Superhero Boom in the first place. By the time Claremont left Marvel in 1991, he and his various artistic collaborators had turned the X-Men into the best-selling characters in comics, spawning a thicket of interconnected monthly series that were as thrilling as they were byzantine. Those hot titles were instrumental in creating an unwieldy speculator’s bubble wherein certain comics were marketed as collector’s items and sold off at ridiculously inflated prices in secondary markets. The bubble burst in 1993, sending Marvel into the tank, and in those panicky years, the company held a fire sale on movie and TV rights.

Enter Donner, a supremely unlikely fit for the caped-crusader world. She was working for Fox at the time and was already a veteran producer of decidedly un-superheroic flicks like Pretty In Pink, St. Elmo’s Fire, and Free Willy. Fox was understandably interested in the rights for the X-Men, especially given the success of a children’s animated series about the characters a few years prior, and Donner snapped the mutants up for it. But the popularity of the X-Men only went so far, and a potential X-movie went into development hell for years; even drafts and treatments by crossover geeks such as Michael Chabon and Joss Whedon weren’t sufficient to get the ball rolling. Miraculously, the studio was sufficiently piqued by a pitch from The Usual Suspects director Bryan Singer, and he and Donner got to work.

Mind you, this was a time when spandex was very much off-trend in Hollywood. The last big-budget superhero movie had been Batman and Robin, a film so reviled that its star, George Clooney, has spent years apologizing for it in interviews. Donner and Singer had trouble snagging any huge-name action stars and were forced to play Moneyball, hiring undervalued character actors (Ian McKellen, Patrick Stewart) and virtual unknowns (she’s particularly proud of pushing the powers that were to hire an Australian newbie named Hugh Jackman). Matters were made worse by the fact that there was no geek-media ecosystem to build buzz and barely any CGI capable of showing believable flight and energy blasts.

“You don’t understand — Bryan, myself, and our editor were in the editing room, and we were convinced we would never work again,” the graceful Donner says while hunched over a table in a Frank Lloyd Wright–esque British Columbian building that doubles as the HQ for Legion’s good guys. “If we had gotten a bad review, it would have killed the whole franchise.” Of course, nothing of the sort happened, and 2000’s X-Men was a smash that enabled a chain reaction of megahit superhero movies from an array of studios. Donner’s own franchise never went away, either: The X-Men cinematic universe has spawned nine films to date, with a tenth, Logan, on the way this spring. She built a reputation as a clear-eyed and warm business partner, engaging everyone from veteran geek progenitors like Claremont to eager youngsters like Jennifer Lawrence, who Donner signed to her first tentpole role in 2011’s X-Men: First Class.

But by early 2015, she feared the franchise she’d built — by then co-stewarded by writer-producer Simon Kinberg — was eating itself and that the entire superhero genre was fast approaching a change-or-die moment. “Our mandate always was, Don’t repeat yourself,” she says, lightly poking her finger forward in the air with each of those last three words. “I just drive Bryan and Simon crazy because I would say, ‘We’ve used a character that had been in two of the other movies! There’s 45, 40 years of X-Men comics! There’s enough stories to never have to repeat ourselves!’”

Cultured intellectual that she was, Donner felt the ideal place to test something ambitious was on prestige cable. She set her sights on Fox-owned FX, home of unconventional fare like The Americans, American Horror Story, and, yes, Fargo. Donner and Kinberg approached its helmer, Hawley, with an existing pitch. He made a counteroffer. “Noah said, ‘Can I just take a character and run with it?’” Donner recalls. “I said, ‘Absolutely.’ And then he came back and said, ‘I’m going to do the deconstruction of a villain.’”

That recollection, of course, further muddies the teeming waters of Legion— is David going to go full Walter White and tear the world down with him as he goes from troubled 30-something to a lord of chaos? Hawley is mum on that point but says he thought David would allow him to poke at reality. “I wanted to explore identity as a product of narrative,” he says in his gently nasal monotone. “The fact that you’re sitting there today, telling yourself, This is who I am, and it’s based on the fact that in high school this girl broke up with me, or I overcame this obstacle in my 20s, and that taught me this. What if all those experiences were false?” Hawley had been a reader of Claremont’s X-Men material, and the early Legion appearances appeared in his mind. He had his muse.

He assembled a team, and nearly all of them say they signed up because of Fargo and Noah’s artistic charisma, but have been unable to subsequently figure out what Hawley’s vision for Legion is exactly. I ask Jean Smart, the glamorous character actress and Fargo alumna, who plays the mutants’ den mother, how Hawley described the show to her. “Well, he didn’t, really,” she says after a pause. “I just kind of went on faith, you know.” She, like the other performers, has only learned about her character bit by bit as each script comes in — and when Hawley shot the pilot, in which she only briefly appears, he hadn’t told her anything about the person she was playing. “It’s been kind of a learning process,” Smart adds with an earthy chuckle.

“This show exists in Noah’s head in a way that I’ve never dealt with before,” says Wylie. “Usually on a show, the writer or the creator will say, ‘It’s kind of this and it’s kind of that and this character’s arc is from here to here.’ We didn’t really get any of that at all.” Instead, Hawley provided his cast and crew with found images and broad-stroke tonal ideas, often at ungodly hours. They all speak of his notorious 3 a.m. emails, in which he’d send around pictures of early-20th-century trick-or-treat costumes or declare that he’d decided what color an extra’s jumpsuit should be. “I think he never stops,” says costume designer Carol Case. “Or, at least, his brain never stops.”

That said, he’s not an issuer of edicts so much as a suggester of overall directions. In fact, his crew are often surprised at how much he expects them to improvise. Wylie recalls having a non-sequitur idea to paint a mural of various Sid and Marty Krofft characters on one set. “Noah’s quote was, ‘This is a story told from the point of view of an unreliable narrator,’” Wylie says, “and for a production designer, that’s just incredible, because it frees you from having to worry about continuity and whether somebody would buy the fact that there’s a Sid and Marty Krofft mural in a pool, because who cares? This may not have ever happened!”

That commitment to uncertainty and confusion stems in no small part from the ghost who lingered around the production and haunts the finished show: Stanley Kubrick. Hawley was somewhat obsessed with the late giant, constantly preaching his virtues to those who work for him, which should be obvious to any cinéaste who watches Legion. It has 2001’s unpredictable physics and curvy futurism, the paranoiacally masculine energy of The Shining, and the ominous smiles and lurid pastels of A Clockwork Orange (in fact, the institution is called Clockworks Psychiatric Hospital — another bit of on-the-nose referencing), and it shares Kubrick’s overall fixation on the wonder and terror of the incomprehensible.

But other personalities have been absorbed into Hawley’s brain, too: the sequences in which David’s compatriots explore his brain are plucked from Tarkovsky’s Solaris; there’s a bloated creature who evokes the beast behind the diner in Lynch’s Mulholland Drive; and the scenes showing David’s mutant powers are built on a foundation of practical effects, a technique prized by Bryan Singer in the X-Men films that the show is otherwise so unlike.

The result is something that is, despite its anachronistic setting, eminently of the present moment. That’s partly because it’s a marriage of two of modern entertainment’s dominant modes: prestige-cable auteurism and stories about paranormal do-gooders. But it’s also a perfect story about the rapidly crumbling American mind, inside of which warring and unyielding voices shout so loud that the very concept of objective reality seems like too much to hope for. Nevertheless, Hawley sees a light at the end of the tunnel for David and anyone who feels like him.

“Here’s a guy whose life was closed off and now it’s opened up in this amazing way,” Hawley says. “The story should feel the same way.” The character, like Hawley and Donner and their producers at Fox, takes a leap of faith into the unknown and, in the process, takes a giant evolutionary lurch forward for the rapidly ossifying superhero genre. A statement David says just a few minutes into Legion’s first episode might well apply to the genre as a whole and serve as Donner and Hawley’s rallying cry: “Something new needs to happen soon.”

*This article has been updated to reflect how many series Noah Hawley has created.