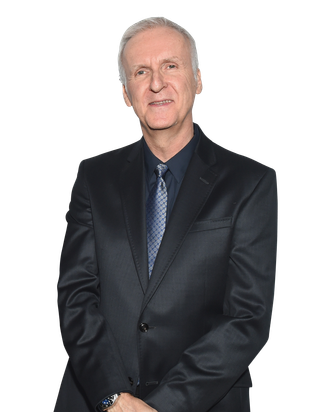

America hasn’t gone the way of Atlantis just yet, but James Cameron isn’t sure we’re all that far off. He’s the executive producer of Atlantis Rising, a new National Geographic documentary airing on January 29 that seeks answers about whether or not the storied lost city really existed and, if it did, what happened to it. According to an allegory in Plato’s dialogues, Atlantis was a mighty and advanced civilization that became too proud and was destroyed by the gods — a notion that might hit a little too close to home in early 2017. Ahead of Atlantis Rising, Vulture caught up with the filmmaker behind Aliens, Terminator, and Avatar to talk about using his movies to fund scientific research, his childhood reading habits, and his trepidation about the upcoming Alien: Covenant.

So, civilizations destroyed by their own hubris! See any relevance to that whole idea right now?

Sure, absolutely. Nobody would deny that there’s a lot of free-floating anxiety out there right now about the political state of affairs globally, and especially in the U.S. And so there are rumbles of social collapse that aren’t far away in the imaginations of some people. I think there’s going to be fascination with some of these lessons from history. I think we can take lessons from the Romans as well, who threw out democracy in favor of a republic that was ultimately dominated by dictators. I think we should look to the past. History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes. We could wind up rhyming with thoughts of past fallen civilizations.

What about the ongoing assault on science at the highest levels of government? That must be horrifying for you, as someone who cares a lot about science education.

Y’know, science is very acceptable when it’s providing us with shiny new baubles. We love to cherry-pick from science the things that we enjoy as technological products, but we don’t like to credit the scientific method that got us there. In my personal philosophy, the scientific method is the only path to truth, because it’s robust, it’s peer-reviewed, and people argue. They don’t just accept speculation and opinion. I don’t think there’s enough public respect for this process. Systematically dismantling the agencies that are designed to protect us and take science and apply it to our lives — I see us going backwards. I’ve said for years that you could drive a stake in the ground somewhere around the beginning of the Bush era. We’d gone through centuries of enlightenment and putting a certain faith in science, and that’s the point at which we just started to ignore it.

What do we do about it? I think, as people in media, we have to not create this false equivalency that the news outlets love to do. Climate is a classic example of that. You have 99 out of 100 experts who agree that climate change is real, that we’re doing it. Then you’ve got one mook that says no, and they put two guys on a show and it looks like it’s an actual controversy when it’s not. It’s about as settled as the theory of gravity at this point. We as a society have to put more emphasis on teaching critical thinking and science in schools.

Why look for Atlantis now?

I think we’re always looking for Atlantis. People have been looking for Atlantis for 500 years. I think we’ll still be looking for it in 500 years. It intrigued me as a kid who grew up on science fiction and fantasy and Robert E. Howard and Conan and all that stuff. As you get older, you apply a little discipline and rigor to it, and I’ve made a kind of layman’s study of archaeology of the Mediterranean area. You think, What was the basis of this myth, this legend? You trace it back and, of course, it all comes from one source, which is Plato — his dialogues, Critias and Timaeus. And you start to think, Is this all just a made-up story, or is it based on something? In the same way that Troy was found by exploring a legend.

My other perspective on this is that I’ve done a fair bit of marine forensics — deep exploration and so on. I know that oceanography, in general, is poorly funded, and archaeology is very poorly funded, and so I think, Alright, fine, if we can do a search for Atlantis that’s going to yield something, that’s going to allow the filmmaking side of my life to support the scientific side. People are always fascinated by it, so we raised some money for a show and we go out and get some divers and archaeologists.

That’s an interesting idea, using entertainment projects as platforms for backing scientific research. Is that a replicable model?

Sure, I’ve been getting backdoor funding for oceanography and marine science and marine forensics and archaeology for years now. I’ve done eight deep-ocean expeditions, and they’ve all been at least partially funded by film projects. The films that we make are market-driven. They’re based on the demand, the curiosity, and interest of the audience. It’s easy to get a film funded to go to the Titanic, but how many times can you do that? So, this is a way to do some legitimate Bronze Age archaeology on a film budget, and National Geographic loves that. They love that model, because they know they’re popularizing archaeology, they’re popularizing ancient civilizations, and it’s a business model and it works. The archaeologists like it because they get to go do digs.

One of the things that breaks my heart, and we showed it in the show, is the Akrotiri ruins in Santorini. That’s a 3,500-year-old civilization, and only about 4 percent of those ruins have actually been dug up, because there’s no money to do it. The Greek government has no money to dig up their own ancient civilization. Which is pretty amazing. You’d only have to throw tens of millions of dollars at it and you could unearth an incredible treasure trove of ancient ruins and arts and culture, and we could maybe understand that. But right now, we’re just getting a glimpse through a keyhole because the funding’s not there, because we don’t put enough emphasis on it as a society.

Why does …

You didn’t ask me if we found Atlantis!

Well, I’ve seen the ending. Do you want to spoil it for our readers?

We found some very, very intriguing clues that didn’t exist before. And we do a nice, general roundup of the favored theories that are out there right now, so for somebody that doesn’t know much about Atlantis, this is a great primer. But then we go well beyond doing a primer to actually doing some new research. So I’m pretty proud of the show for that reason. Did we find Atlantis? I guess you better watch the show to find out.

Why does Atlantis keep kicking around in the popular imagination?

I think it’s a lot like the Titanic. It’s a parable about hubris, it’s about the gods punishing man, and it’s about something that has been taken away and is now hidden from us. The dynastic Egyptian period was buried in sand, but it’s been well dug up. The mystery has been taken away from that. The Romans left their mark all over Europe, and we know where the ruins are, and they’ve been well dug up and well-described. So I think it’s the fact that there’s this idea that there might be a civilization on that same orbit, that same scale, that’s out there that’s never been found.

I personally don’t believe that. I think there isn’t an Atlantis on that scale some place out there. I think there might be something that hasn’t been found yet, maybe outside Thassos, which I think is a good candidate, that is a significant civilization that led down through the ages to what Plato described. By down through the ages, I mean the ages before Plato, so Plato’s points were 2,400 years ago, and he’s talking about thousands of years in his past, so you’re getting into the midst of time where there’s not great record keeping. Not much has come down to us, other than piles of stones that are intriguing and enigmatic.

On a completely different topic: How do you feel about the upcoming Alien sequel, Alien: Covenant?

The franchise has kind of wandered all over the map. Ridley [Scott] did the first film, and he inspired an entire generation of filmmakers and science-fiction fans with that one movie and there have been so many films that stylistically have derived from it, including my own Aliens, which was the legitimate sequel and, I think, the proper heir to his film. I sort of did it as a fanboy. I wanted to honor his film, but also say what I needed to say. After that, I don’t take any responsibility.

I don’t think it’s worked out terribly well. I think we’ve moved on beyond it. It’s like, okay, we’ve got it, we’ve got the whole Freudian biomechanoid meme. I’ve seen it in 100 horror films since. I think both of those films stand at a certain point in time, as a reference point. But is there any validity to doing another one now? I don’t know. Maybe. Let’s see, jury’s out. Let’s see what Ridley comes up with. Let me just add to that — and don’t cut this part off, please — I will stand in line for any Ridley Scott movie, even a not-so-great one, because he is such an artist, he’s such a filmmaker. I always learn from him. And what he does with going back to his own franchise would be fascinating.

With all these bloated franchises and collapsing civilizations, how optimistic are you about the world right now?

I always say, as a father of five, it’s my job to be optimistic. Look, there’s a lot of negative indicators. We’re sliding right now. We’re in a skid. We need to start controlling that skid, and right now we’re not steering into it, we’re just making it worse. I think anybody that has a conscience and is socially responsible and well-informed has to stand up and make their voice louder right now.

This interview has been edited and condensed.