Last year, when we were putting together “The 100 Jokes That Shaped Modern Comedy,” our goal was to present a list of jokes that captured the entirety of capital-C comedy. While we feel like we succeeded in that mission, we also came away wondering if the scope had been too limited — if there were jokes outside the sphere of stand-up, sketch, radio, TV, and film that helped establish what we think of as comedy today. Between that and some difficult omissions the first time around — Martin and Maude, Monty Python and the Kids in the Hall — we realized a second edition was warranted, one that pushes the bounds of what could be called a “joke.”

On this list you’ll still find traditional setup–punch-line zingers and acts of physical comedy, but we no longer demanded that a joke be performed. This time we considered passages from novels, cartoon images, and even pieces of art. A joke, as we used it, is a unit of comedy. Unlike last time, non-American acts were eligible for inclusion if their work was popular at the time in the United States and had an influence on specifically American comedy. We’ve also decided, with very few exceptions, not to duplicate anyone from the first list. Of course, the greats have had multiple dimensions to their influence, but our objective with this list is to tell more stories, and that meant no repeats.

The list was put together by Jesse David Fox, Bill Scheft, Dan Pasternack, Yael Kohen, Mike Sacks, Christopher Bonanos, Hunter Harris; E. Alex Jung, Abraham Reisman, Andy Beckerman, Naomi Ekperigin, Andy Evans, Bridget Flaherty, Halle Kiefer, Jenny Jaffe, Elise Czajkowski, Ramsey Ess, Jake Kroeger, Matthew Love, Katla McGlynn, and Dave Schilling.

With that preamble out of the way, here are 100 More Jokes That Shaped Modern Comedy. They are listed in chronological order, and you can use the timeline on the left to jump to different eras or specific jokes.

Why Did the Chicken Cross the Road?

Mr. Tambo: Say, boss, why did the chicken cross the road?

Interlocutor: Why, I don’t know, Mr. Tambo, why did the chicken cross the road?

Mr. Bones: To get to the other side!

Minstrel is considered the original sin of American show business. The history of the country cannot be separated from the fact that it was built on the backs of black slaves, and the history of modern comedy cannot ignore that it started with white men in blackface. This includes the first joke most Americans learn as children, which has its roots in 19th-century minstrelsy. “Why did the chicken cross the road? To get to the other side” was one of a handful of riddle-gags frequently used by Christy’s Minstrels, a group of blackface entertainers, formed by Edwin Pearce Christy, who would go on to become the most famous minstrel troupe ever. (An 1847 issue of The Knickerbocker magazine is credited as the first to print the joke; however, it is unclear where the joke started. Likely it began as a folk joke that the Christy’s adapted.) The group is credited with inventing or at least popularizing “the line,” the name for the three-man act that would be the focus of the first of a three-act minstrel show, with the “interlocutor” in the middle, between “Mr. Tambo” and “Mr. Bones.” Rhetorical question-and-answer bits like “Why did the chicken cross the road?” were performed as a rapid-fire dialogue between the three. It was a precursor to the vaudeville two-man act, and thus a precursor to essentially all future comedy. The influence of the joke, and white minstrel shows in general, on the form is complete and total, but it shouldn’t be ignored that the goal was affirming white supremacy. The fight for fair representation of black people in comedy continues to this day, over a century and a half later; however, white minstrel shows would soon fall out of fashion in favor of black minstrel shows, burlesque, and, eventually, vaudeville.

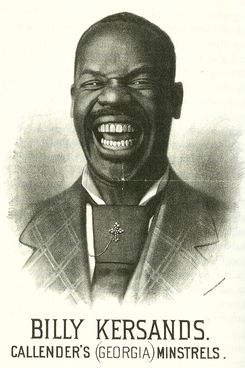

Billiard Ball Trick

[While stuffing two billiard balls in his mouth] “If God had made my mouth any bigger, he would have had to move my ears.”

After the Civil War, minstrel shows starring white actors in blackface fell out of favor and in their place arose a number of bllack minstrels. None was more popular than Billy Kersands. Famed vaudeville comedian Tom Fletcher wrote, “In the South, a minstrel show without Billy Kersands is like a circus without elephants.” Though he eventually wrote the lyrics of the song that led to Aunt Jemima becoming a pancake icon, Kersands’s greatest gifts were physical. “The slightest curl of his lip or opening of that yawning chasm termed his mouth was of itself sufficient to convulse the audience,” said an observer. One could only image the response to his billiard-ball trick. Still, that joke underlines his complicated legacy. Kersands’s act affirmed many of the worst stereotypes of the slow-witted Sambo character seen in white minstrel shows. As a result, many blacks, particularly in the north, opposed his act. That said, Kersands had more black fans than white, and his popularity resulted in theater owners relaxing their segregation policies. Also, although his performance – especially from a modern perspective – might be seen as horribly offensive, it was more nuanced and human — even if only slightly — than those of white minstrels and incorporated some black folk traditions. As black-comedy historian Mel Watkins writes in his book On the Real Side, Kersands was likely the first black comedian to face what would become a recurring dilemma from Stepin Fetchit to In Living Color: “the conflict between satirizing social images of blacks and contributing to whites’ negative stereotypes of blacks in general.”

Way Down in Front

“And way down in front by the footlights’ glow /

The bald-headed men sat in the front row. /

They had big glasses to see all the sights /

Including the blondes who danced in silk tights.”

Modern-day burlesque may be synonymous with stripteases and tassels, but when Lydia Thompson and her “British Blondes” first hit America in 1868 with their show Ixion, their style of Victorian Burlesque was as much about bawdiness of mind as of body. Their parody musicals mocked the traditions of theater and opera, often featuring female characters in traditionally male leads and spoofing popular songs of the day. Within a year of Thompson’s arrival, the New York Times was declaring a “mania for burlesque,” despite the paper’s evident snobbery about this newly popular theatrical style. In the first wave of American burlesque, the productions were female-led and the costumes were revealing — above-the-knee dresses and tights — making them a risqué treat for the audiences who flocked to the shows. Since most of the music used was stolen outright from other works, they kept few records of their performances, but their influence was enormous, spawning troupes around the country and a style that remained popular for decades, offering a high-brow alternative to minstrel shows and setting up the rise of vaudeville. It also goes to show that women have been telling dirty jokes as long as women have been allowed to tell jokes, a legacy that continues to this day.

‘I Am the Very Model of a Modern Major-General’

Major General Stanley: I am the very model of a modern Major-General /

I’ve information vegetable, animal, and mineral /

I know the kings of England, and I quote the fights historical /

From Marathon to Waterloo, in order categorical /

I’m very well acquainted, too, with matters mathematical /

I understand equations, both the simple and quadratical /

About binomial theorem I’m teeming with a lot o’ news [bothered for a rhyme] /

With many cheerful facts about the square of the hypotenuse.

Gilbert and Sullivan had written a hit in London, H.M.S. Pinafore, and set sail for New York to stage it there. Only, nobody was interested in going to see it since copyright law didn’t extend to foreigners at the time, and a number of theater companies had already staged the show in America. The solution? Stage a new production in America, copyright it there, and beat the pirates at their own game. The classic comic opera The Pirates of Penzance would go on to feature the best example of their influential modernizing of the patter song — “The Major-General Song.” Made up of many types of humor — wordplay, references both historic and cultural, social satire (a “modern” military man must be educated rather than brawny), and even meta humor (“that infernal nonsense Pinafore!”) — the funniest and most lasting part remains just how absurdly fast it is, setting a comedic pace soon seen in vaudeville. The song brought the house down in 1879 and it’s still frequently parodied today. You may not know any of the hundreds of words, but I’ll bet you know the tune, and there aren’t a lot of Victorian-era operatic songs that can claim that.

Fools in Town

the king: Cuss the doctor! What do we k’yer for HIM? Hain’t we got all the fools in town on our side? And ain’t that a big enough majority in any town?

Mark Twain’s most famous work is best known for its biting commentary on racism and the Victorian panic over corrupted youth, but just as important is Twain’s satire of man as a whole. The young boy Huck and runaway slave Jim encounter two con artists, referred to as the king and the duke, who don’t just exploit their fellow man, they play them like fiddles. The two criminals disagree on whether they should quit while they’re ahead, since the doctor in the town that they are swindling has figured them out. The king says the above, not only winning the argument, but taking down every town in America in one fell swoop. There were plenty of people speaking truth to power and writing things that made people think back then, but when’s the last time you heard about somebody reading John Esten Cooke for fun? Twain was able to make his point stick because you laughed when you heard it, by rooting the jokes in specifically funny character, not just turn of phrase. There’s a reason, after all, that the Kennedy Center award for humor is called the Mark Twain Prize: So much of what we think of in terms of modern comedy comes from this revelation.

“Bunburying”

Jack: If I marry a charming girl like Gwendolen, and she is the only girl I ever saw in my life that I would marry, I certainly won’t want to know Bunbury.

Algernon: Then your wife will. You don’t seem to realise, that in married life three is company and two is none.

Jack: [Sententiously]. That, my dear young friend, is the theory that the corrupt French Drama has been propounding for the last fifty years.

Algernon: Yes; and that the happy English home has proved in half the time.

The wittiest piece of theater from one of the wittiest playwrights to pick up a pen, Earnest is not just a playful comedy of manners about marriage but a subtly subversive take on the life and times of Oscar Wilde himself. At first blush, the story of upper-crust gadabout Jack and his pal Algernon is about coupledom, class, and fibs told in the pursuit of love; scratch the surface, and it’s about identity, willful blindness, and the strains of living a double life in 19th-century London. Amid all the repartee and revelations about babies abandoned in handbags, Algernon’s notion of “Bunburying” sums up the play perfectly — and Wilde’s dilemma as a married man who was, at least, bisexual. While looking to avoid bland social engagements, Algernon pretends to care for sick friend “Bunbury” somewhere in the country; this mirrors Jack’s relationship with his nonexistent brother, Ernest. Wilde’s way with words has since helped spawn a culture of highbrow banter — one adopted by both gay and straight comedy alike — and elevated comedy, generally, as a form to be treated with respect. Earnest’s subtitle says it all: “A trivial comedy for serious people.”

‘Indefinite Talk’

Moreland: What kind of races do you play?

Russell: Horse races.

Moreland: What track you play at?

Russell: I play at —

Moreland: That track’s crooked. Why don’t you play over here, around —

Russell: That’s where I lost my money.

Moreland: How much did you lost?

Russell: I lost about —

Moreland: You didn’t have that much.

Flournoy Miller and Aubrey Lyles, a duo that started as a simple two-man act, later ushered in the Harlem Renaissance. Friends as children, it was not until Miller and Lyles re-met in college that they began to write and perform together. In their partnership, Miller and Lyles created a bit that became the basis of many Vaudeville routines and is sometimes called the black “Who’s on first?” Many others would replicate the back-and-forth candor, not only black performers like, most famously, Mantan Moreland & Ben Carter, but white as well, including Abbott and Costello and Amos ‘n’ Andy. (Miller would eventually write for the TV version of Amos ‘n’ Andy.) Less a scripted sketch than a form, the idea of their “indefinite” talk was to anticipate the end of each other’s sentences and to progress the dialogue forward. By the 1920s, the comics wrote and starred in Shuffle Along, a legendary Broadway hit (which had a Tony-winning revival in 2015), but “Indefinite Talk” would prove to be their most lasting contribution to comedy. Comedians were performing it well into the 1950s, like the version below from Rock ‘n’ Roll Revue, one of the era’s black variety showcase films (a notable time in the depiction of African-Americans in the movies, in its own right). Beyond that, even if the specific routine fell out of favor, as people moved beyond vaudeville, its influence was tremendous and foundational, helping define how American comedic dialogue would sound.

Fountain

Marcel Duchamp, like all who were a part of the Dada movement, was interested in asking profound questions about the nature of art and disturbing the status quo. This is why, in 1917, he bought a standard urinal from a plumbing supply store on Fifth Avenue, signed it with the moniker “R. Mutt,” and requested that it be displayed in a gallery with the title Fountain. In and of itself, it’s a joke told at the expense of a stuffy art world, but its reach extended much further. Duchamp, arguably, unwittingly created the first widely celebrated piece of anti-comedy. There’s a reason Andy Kaufman is often called Dadaistic. Kaufman shared a similar interest in confronting what would get a reaction from an audience. Duchamp asked why a pee pail couldn’t be art in the same way Andy Kaufman asked his audiences why just reading The Great Gatsby or singing “I Trusted You” over and over (and over) again wasn’t comedy. It’s not just Kaufman; it’s Steve Allen wearing a suit covered in tea bags; it’s David Letterman throwing things of the roof. It’s a spirit that has run through comedy ever since. Every time someone like Norm MacDonald stands up to read dad jokes at a roast or Tig Notaro spends most of her late-night set just pointing out the funny sound a stool makes when she drags it across the floor, it’s easy to sense the trickle-down effect from Fountain.

The Clock

Harold Lloyd’s bespectacled everyman was as thoughtfully crafted a silent-comedy creation as Charlie Chaplin’s “Little Tramp” or Buster Keaton’s “Stone Face.” Hapless and helpless in the face of wild adversity, Lloyd would somehow always persevere … but just barely, in a trick Jackie Chan would eventually bring to his comedic fight scenes. The iconic sequence featuring Lloyd dangling from the hands of a giant clock on the face of a skyscraper is inarguably one of the most enduring images in all of cinema history. Audiences were thrilled, although reports of fainting in movie houses during the final daring sequence were common. Lloyd’s death-defying stunt is made even more astounding by the fact that he performed it with the use of only one full hand, having lost his thumb and index finger in an accident in 1919 — a loss that he concealed in his subsequent films with the aid of a flesh-colored glove. Physical and stunt comedy is forever indebted.

“Regusted”

Amos: Don’t try to tell me. The way we is goin’ now, we is just starvin’ to death, that’s all.

Andy: Now, listen, Amos, you just stick to me and you’ll be rich. What would you think if you wake up some mornin’ an’ put your hand in your pants pocket an’ found a roll of 20-dollar bills?

Amos: I wouldn’t think nothin’. I’d know I had on somebody else’s pants, that’s all.

Andy: Don’t get me regusted. Shut up.

In 1926, as admirers and students of the minstrel comedy teams of the era, Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll created the black-dialect-driven duo Sam ‘n’ Henry. Two years later, after changing the name of the act to Amos ‘n’ Andy, the two white men would create and star in radio’s first big hit show, becoming what many regard as the most successful in the history of the medium. Jokes like the above were essentially “blackface” on the radio, but the show’s appeal and impact were undeniable. When viewed in history’s rearview mirror, the malaprop-inflected dialogue is cringe-worthy, but in its heyday, it was embraced by white and black audiences alike who identified with the struggles of the striving characters throughout the Great Depression and after. The duo’s depiction of African-Americans, which went beyond one-note jokes, was, at the time, a major step forward in representation compared to the minstrel holdovers and Hollywood movies of the early-20th century. Still, looking back now, 90 years later, the show was undeniably problematic. Ironically, it was the television adaptation of Amos ‘n’ Andy, which starred an all-black cast, that became a lightning rod for controversy, ultimately facing cancellation in 1953 under pressure from groups like the NAACP. (Beulah, television’s other successful comedy with a black central character also disappeared that same year.) Following Amos ‘n’ Andy’s demise on the small screen, television would not have another comedy series with an African-American lead character for 15 years, until Julia starring Diahann Carroll debuted in 1968.

‘Resumé ’

Razors pain you;

Rivers are damp;

Acids stain you;

And drugs cause cramp.

Guns aren’t lawful;

Nooses give;

Gas smells awful;

You might as well live.

Life among the journalists and theater folk who frequently lunched at the Algonquin Hotel made poet, critic, and short-story writer Dorothy Parker a paragon of sophisticated wit; but her world wasn’t just the plays, booze, trysts, and bon mots that suffused her prose. Parker thrived in moments of emotional distress and consequence: the backstage jousting between men and women (“The Sexes”) or the morning after the bender (“You Were Perfectly Fine”). And though she died of a heart attack at the age of 73, she thought a lot about ending things early. The eight-line poem Resumé just might be literature’s sharpest and most succinct evaluation of suicide, and it indicates Parker’s willingness to use even the darkest and most crippling aspects of her depression as grist for the mill. Parker’s heirs are not only those who give biting, literary critiques, such as Fran Lebowitz, but the comedians who dwell in darkness, and who use quips to do battle with the world and their own worst impulses — including present-day comics such as Maria Bamford and Chris Gethard, who grapple with mental instability directly.

‘The Son of a Bitch Stole My Watch!’

Set in a bustling Chicago press room, this classic American play follows the exploits of one Hildy Johnson, a plucky reporter bound and determined to get married and leave the news game altogether, as well as Johnson’s wily publisher Walter Burns and a hard-bitten gang of reporters. When a huge story nearly falls into Johnson’s lap — in the form of a condemned man on the lam — the shenanigans with crooked mayors, bedraggled mothers-in-law, and roll-top desks takes over. Former reporters Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur elevate the action and vernacular of the ragtag newsroom, giving it all the melodrama, histrionics, fabrications, and exclamations of a tabloid rag. Even after the smoke clears, the switcheroos don’t stop. After the possessive Burns has gifted Johnson with a pocket watch and watched the retiring reporter exit with his bride-to-be, Burns calls the police: Johnson, he says, stole that watch and should be arrested. The explosive, rapid-fire dialogue has made The Front Page not only a film director’s delight, but goosed an entire generation of Hollywood screenwriters in the ’30s and ’40s — and also influenced latter-day stylists such as the Coen brothers.

‘I Don't Want To Get Thin’

“I noticed one thing, girls, you can store this in your dome /

All the married men who run after me have skinny wives at home”

Born Sonya Kalish to an American-bound Ukrainian-Jewish family, Sophie Tucker styled herself “The Last of the Red Hot Mamas.” Her brassy stage presence and ribald tunes translated across vaudeville to radio and film, making her one of the most well-known stage acts in the first half of the 20th century. Playing up her size with songs like “Nobody Loves a Fat Girl” and “I Don’t Want to Get Thin,” and appealing to her Jewish fan base with tunes like “My Yiddish Momme,” Tucker achieved her greatest success in the 1920s, both in America and Europe. Her larger-than-life character influenced later female performers like Ethel Merman, Carol Channing, Roseanne Barr, and Bette Midler, who channeled Tucker’s stand-up in her 1980 concert film Divine Madness.

Hattie and Stepin

[Aunt Dilsey turns around to walk away with a tray of drinks she just poured, so Jeff Poindexter tries to steal a doughnut.]

Aunt Dilsey: [Turning around] Hey!

[Jeff drops the doughnut and his tambourine.]

Cut them monkey shines. How do you expect the judge to win his croquette game with no solace in his stomach?

[Aunt Dilsey walks out of the kitchen and Jeff picks up his tambourine]

Jeff: [Talking with his tambourine next to his face, like it were a hand trying to hid a secret] Aunt Dilsey you forgot the jug. The jug here. Alright, you can’t say I never told you now. Leaving somebody here with all this stuff. [Jeff puts food in his pocket] I bet she’s gonna blame me.

A comic actor of great talent, who used it — some say cynically for his own personal gain — to reaffirm the most grotesque stereotypes, there’s maybe no more complicated figure in the history of American comedy than Stepin Fetchit. Still, playing his character The Laziest Man in the World, Fetchit became the first black movie star at a time when black representation in film was essentially nonexistent. In retrospect, though Fetchit would still be popular for some time afterward, this moment from Judge Priest, a film starring comedy icon (and friend of Fetchit’s) Will Rogers, can be seen as a moment of transition in American comedy and the representation of black people in popular culture. At the time, Hattie McDaniels was still unknown, but she impressed director John Ford so much while filming that he cut scenes from Fetchit to give her more screen time. Though McDaniels is playing a servant, a role she’d go on to play frequently (eventually becoming the first African-American to win an Academy Award for playing one in Gone With the Wind), she is self-possessed and sharp. She makes the joke; she isn’t made into one. She eventually would face criticism as well for fulfilling the role of a mammy, but the fact that she was free to talk back to men and white characters in film was undoubtedly a step forward. She did it with a quick turn of phrase or a simple, hilarious look.

The Three Stooges As Doctors

Voice-over intercom: Calling Dr. Howard, Dr. Fine, Dr. Howard! Dr. Howard report to room 66! Dr. Fine, 72! Dr. Howard, 83!

[The Stooges run in and out of various doors.]

Voice-over intercom: Dr. Howard, Dr. Fine, Dr. Howard, report to Dr. Graves’s office.

[They run into Dr. Graves’s office.]

Larry: Hello, captain, you send for us?

Dr. Graves: Yes. How did you find that patient in 66?

Moe: Under the bed.

Dr. Graves: How did you find the patient in 72?

Larry: Up on the chandelier.

Dr. Graves: What did you do for him?

Curley: Nothin’! What’d he ever do for us?

Dr. Graves: What are you working here for?!

Stooges: For duty and humanity!

Voice-over intercom: Calling Dr. Howard, Dr. Fine, Dr. Howard!

[The Stooges run out of Dr. Graves’s office with a flurry of Curly “whoop-whoops,” slamming and shattering the glass door behind them as they run off. The custodian nonchalantly strides up with a replacement pane for Dr. Graves’s glass door.]

The best work of this decidedly lowbrow trio of violent slapstick comedians occurred between 1934 and 1946 and featured the perfectly balanced lineup of Moe Howard, Larry Fine, and Curly Howard. The Academy Award–winning 1934 short Men in Black casts the trio as inept doctors who, in classic anti-authoritarian tradition, undermine the propriety of their environment as well as anyone of status. Replete with their signature slaps, punches, eye pokes, “nyuks,” and “whoops,” the Stooges run breathlessly for the duration of the short, inflicting quackery and chaos everywhere they go. While the Stooges’ brand of madcap mayhem and unapologetic anarchy wasn’t for everyone, it absolutely endured for generations, remaining a cultural touchstone in the 1983 MTV novelty crossover hit “The Curly Shuffle” by Jump ‘N the Saddle Band, as a running comic point-of-reference by Mel Gibson’s Martin Riggs in the Lethal Weapon franchise, and seemingly as the template for the Jackass crew.

Alfalfa’s Firecrackers

Beginning during the silent-film era, over 200 Our Gang short films were produced in a period spanning over 20 years, introducing moviegoers to a regular cast of disobedient delinquents including Spanky, Alfalfa, Darla, Stymie, Froggy, and Buckwheat, in addition to discovering young stars like Jackie Cooper and Mickey Gubitosi (who would later change his screen name to Robert Blake). For nearly a half-century after their initial release, generations would be raised watching these shorts, inspiring and influencing every film or TV show featuring badly behaved children. It’s impossible to see Home Alone, for example, without thinking that Macaulay Culkin’s violent high jinks are extensions of Rascal pranks like this one. However, enduring for so long also meant that the shorts, which could be seen as progressive at one time for depicting all the children as equal, eventually faced controversy for their portrayal of children of color. Eddie Murphy shined a parodic light on representation in the early 1980s with his inspired take on the verbally challenged “Buhwheat” on Saturday Night Live. The Depression-era shorts faded from view shortly thereafter.

Baby Snooks

Baby Snooks: What’s insurance, Daddy?

Daddy: How many times must I tell you? It’s something I pay for so you can live comfortable when I’m gone.

Baby Snooks: Where you going?

Daddy: I’m not going anywhere.

Baby Snooks: Why?

Daddy: Because I’m not. I just want to be fit in the morning, so I can get this double indemnity policy.

Baby Snooks: What’s a dublimanenity?

Daddy: Well, I certainly stuck my neck out there. Double indemnity means if I die a natural death, I get 10,000 dollars. If I commit suicide, I get 20. Right now, that seems like a pleasant way of making 20,000 dollars.

Baby Snooks: Do it, Daddy.

Daddy: I will not. Now go to sleep.

Today, many people who know the name Fanny Brice are thinking of Barbra Streisand’s Oscar-winning take on her early life in the 1968 musical Funny Girl. But the real Brice was famous for another girl — her character Baby Snooks, a precocious 4-year-old who made Brice a radio phenomenon in the 1930s and ’40s. Brice developed the mischievous child in her days as a vaudeville star, parodying a famous child actress of the time. When she moved to radio, Bryce insisted on dressing in costume to fully inhabit the character, even though the show was only performed before a small studio audience. What charmed listeners of Ziegfeld Follies of the Air (The Baby Snooks Show after that) was the banter between the somewhat sassy (but never mean) little girl, and her exasperated (but never cruel) Daddy, who tried to answer every plaintive “Why-y-y, Daddy?” that his daughter threw at him. But despite the show’s success, it wasn’t a good fit for television; Brice was over 40 when the show started, and even her pitch-perfect baby voice couldn’t sell her as a little girl. The show continued in its radio format until Brice’s unexpected death in 1951, at the age of 59. Her legacy lived on in the comic archetype of the annoying, precocious little kid, which has remained a fixture ever since, as well as the character work of female comedians that came after, especially Lily Tomlin’s Edith Ann, Gilda Radner’s Judy Miller, and Amy Poehler’s Kaitlin.

Fibber’s Closet

Molly: Maybe we better see if the closet door is locked. Let me take a look.

Fibber: Oh, it’s locked all right. You don’t think I’d leave all my personal defects around for some prowler to get his hands on.

Molly: McGee, it isn’t locked…

[The sound of many falling objects and glass breaking.]

Real-life husband-and-wife Marian and Jim Jordan starred in one of radio’s most beloved and longest-running domestic situation comedies, Fibber McGee and Molly. The working-class Midwesterners of 79 Wistful Vista were smart but salt-of-the-earth accessible. The best remembered running gag of the series was Fibber’s overcrowded closet, the contents of which would collapse onto him in an ever-extended cacophony of sound effects. Fibber would always seem to forget the last time, ignoring Molly’s pleas to not open the door. The result was radio comedy at its best, leaving the listener to envision Fibber buried under mountains of rubble in their theater of the mind. The bit continued when the duo transitioned to television, but the visual realization of the closet gag never lived up to the imaginations of their fans. The joke, like many of the era, has been imitated and imitated by numerous comedies since, to the point that it’s origins have been somewhat obscured. But it all started with Fibber’s closet.

‘Tschaikowsky (and Other Russians)’

“There’s Liadoff and Karganoff, Markievitch, Pantschenko

And Dargomyzski, Stcherbatcheff, Scriabine, Vassilenko,

Stravinsky, Rimsky-Korsakoff, Mussorgsky, and Gretchaninoff

And Glazounoff and Caesar Cui, Kalinikoff, Rachmaninoff,

Stravinsky and Gretchnaninoff,

Rumshinsky and Rachmaninoff,

I really have to stop, the subject has been dwelt upon enough!”

In 1941, the great Broadway playwright Moss Hart joined forces with fellow geniuses Ira Gershwin and Kurt Weill on the musical Lady in the Dark, which introduced a then-unknown young performer named Danny Kaye. The song “Tschaikowsky (and Other Russians),” in which Kaye rattled off the hard-to-pronounce names of over 50 Russian composers in 39 seconds, was a showstopper and transformed Kaye into a star. Kaye quickly went into the movies, scoring hit after hit with Wonder Man, The Inspector General, Hans Christian Andersen, and The Secret Life of Walter Mitty. In almost every film, Kaye would perform dialogue and songs that showcased his gift for verbal acrobatics. (Especially notable is the run in the 1956 film The Court Jester about the “pellet with the poison” being in the “vessel with the pestle.”) Kaye’s peerless precision wowed audiences but also provided a high bar that notoriously hard-working, perfectionist performers such as Sid Caesar and George Carlin would both later cite as being of significant inspiration.

Sullivan’s Interrogated

Police: How does the girl fit into the picture?

Sullivan: There’s always a girl in the picture. What’s the matter, don’t you go to the movies?

Sturges not only took the screwball comedy and made it his own, he also pioneered a number of traits that we see the auteurs of today rip off. He had a stock stable of actors whom he turned to again and again, he wrote naturalistic dialogue, and he wrote intricate, fast-paced plots with crazy situations. Oh, and his main character in this film, Sullivan, has a dream movie he wants to make one day called “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” In a Sturges film, even though everybody is clever and everybody immediately knows the right thing to say, like in the case of this joke, it never feels incredibly stylized, proving that witty dialogue doesn’t have to remind you that it was written. Sturges pushed the screwball comedy further down the field, and when he was done, he happily handed it off to the Coens and the Andersons of today.

‘Der Fuehrer’s Face’

“When der fuehrer says, ‘We are the master race.’ /

We ‘Heil! Heil!’ right in the fuehrer’s face.”

Before bandleader Spike Jones became a household name for novelty songs featuring doorbells, barking dogs, and pistol shots, he released a boisterous version of a song from an upcoming anti-Nazi cartoon starring Donald Duck. Just months after D-day and the U.S. entry into WWII, the release of “Der Fuehrer’s Face” struck a nerve by tying nationalism to a derisive sort of laughter. The song’s goofy oompah bounce and mocking repudiation of Hitler’s ugliest edicts, replete with a host of Bronx cheers, quickly made it one of the most popular songs of 1942. The Walt Disney–produced Donald Duck short eventually came out and won an Academy Award, only furthering the legacy of Jones’s version. Though the barely constrained bedlam of Jones’s band influenced everyone from Weird Al to Mel Brooks to Frank Zappa, Jones really made his mark by staring down Hitler and blowing a really loud raspberry.

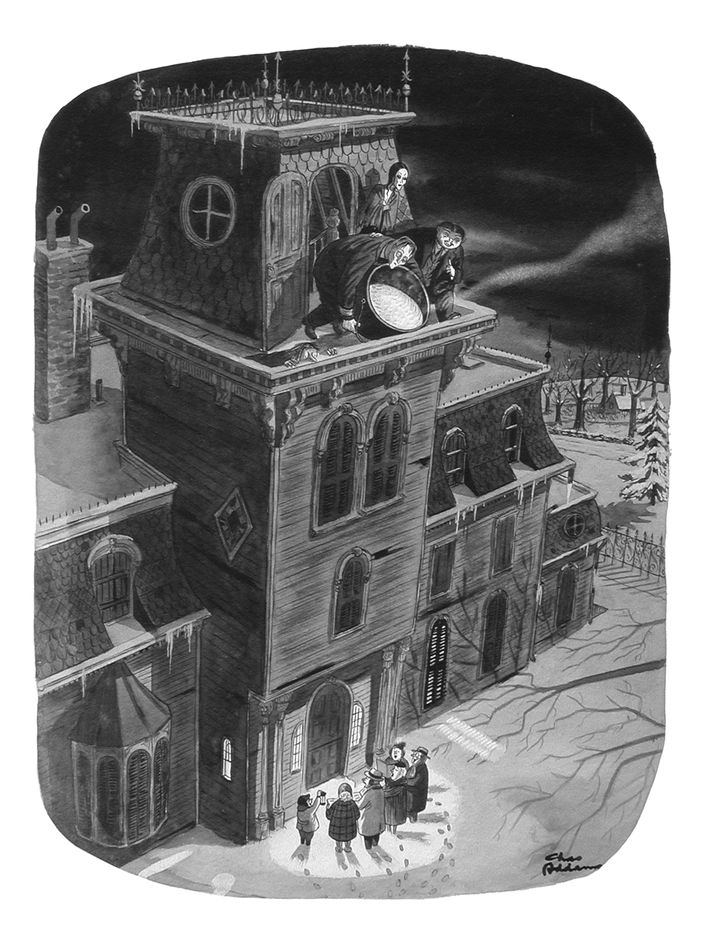

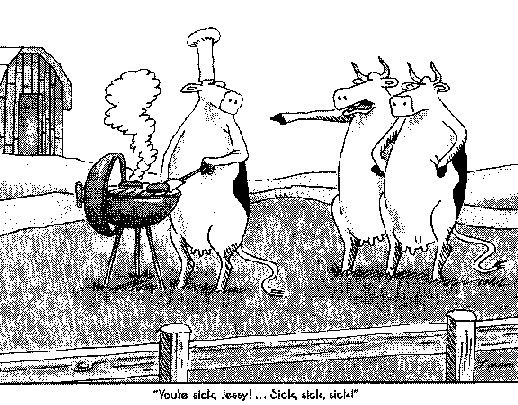

‘Boiling Oil’

Though dark humor speaks to so many people, one does not often associate it with comic strips. But Charles Addams was always a little different. Addams illustrated hundreds of cartoons, mostly for The New Yorker, which would serve as the inspiration for The Addams Family, but one cartoon outshines the rest. In it, your eye immediately focuses at the very top of a Gothic mansion, where three strange-looking humans are about to pour a steaming cauldron over the side of the roof. Slowly, your eye travels downward to see a group of happy Christmas carolers unaware of what is about to happen. The most interesting element here, though, is the use of perspective. The audience is not among the carolers. We are with the ghoulish family. We are overseeing this bubbling liquid and perhaps grinning just as much as the family is. With one simple drawing, Charles Addams taps into something lurking inside all of us, introduced a macabre tone to modern comedy, and paved the way for the entire genre of horror comedy.

Family Photograph

Photographer: Now hold it a minute. Mrs. Goldberg, would you mind removing your hat, please?

Mrs. Goldberg: My hat?

Photographer: You see it throws a shadow on your face.

Mrs. Goldberg: Haha, Jake.

Mr. Goldberg: Molly.

[Mrs. Goldberg struggling to get her hat off.]

Mrs. Goldberg: I can’t get it off.

[Mr. Goldberg helps her remove her hat.]

Mrs. Goldberg: That’s better?

[The Goldbergs smile for the camera.]

The makers of the earliest television shows struggled to figure out what TV even was: vaudeville? Theater? Radio with pictures? The Goldbergs, brought over to TV in 1949 after 20 years of radio episodes, was perhaps the first television sitcom that had most of the form down pat. It doesn’t have the bright clowning of I Love Lucy, which came on the air a year or so later. It wasn’t packed with jokes. It had no laugh track. It was, instead, domestic and sometimes sentimental in tone. It was also mordantly, wryly funny, a gentler Norman Lear show before its time. But with a twist: a woman named Gertrude Berg was both show creator and star, and her on-air family was explicitly Jewish, living in the Bronx and speaking Yiddish-inflected English with the neighbors. (The kids, of course, were all-American, setting up much of the comedy.) In this episode, the Goldbergs are scheduled to take a family photo, but it comes out that Mr. Goldberg doesn’t like any of Mrs. Goldberg’s hats. After some squabbling, they settle on a hat, only to have the photographer tell her not to wear one at all. Neil Simon would take The Goldbergs’ form and run with it; less obviously, so did Norman Lear. Heck, this joke, with some modern punch-up, sounds like it could be from Modern Family. By the time the show went off the air in 1956, the Goldbergs had moved from the tenements to the suburbs, as Lucy and Desi did around the same time, and their life changed as they struggled to assimilate — as did America’s.

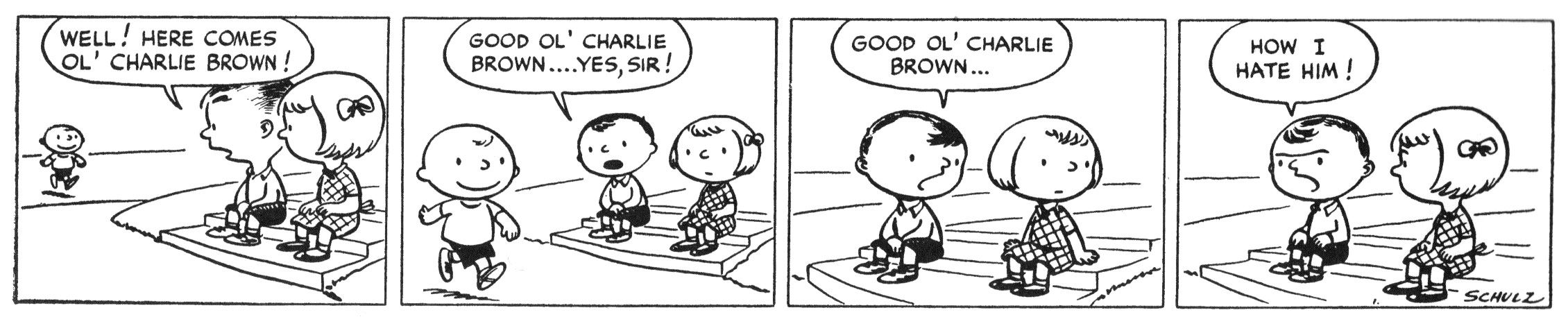

Charlie Brown’s Introduction

Over the 50 years that Charles M. Schulz’s “Peanuts” ran as a daily comic strip, the strip evolved both with the times and against it. Slowly but surely the focus drifted from the human children over to a certain bipedal beagle, and in the process, much of the strip’s ingrained sadness went to the wayside. As beloved as Snoopy is, it is the constant stream of inevitable defeats that make up Charlie Brown’s life that the strip will be remembered for. And it was there from the very first strip. As the strip goes on, we see Charlie be denied baseball wins, a proper kite flight, psychiatric help, and, yes, a chance to kick a football, creating a unique contrast of melancholy and the sweetness expected from a cartoon about a kid. All that complexity of tone was there from the start, captured in just four line-drawn frames. It is a clear influence on every comic that followed, most obviously Calvin and Hobbes, but you can also see “Peanuts” in any character, like The Office’s Michael Scott, who hides a tinge of sadness behind a comic smile.

‘I Yam What I Am’

“‘You want ‘em buttered?’

‘Please.’

‘Sho, that way you can get the most out of ‘em. Yessuh,” he said, handing over the yams, “I can see you one of these old-fashioned yam eaters.’

‘’They’re my birthmark,’ I said. ‘I yam what I am!’”

In 1953, Ralph Ellison was the first African-American author to win the National Book Award for his critically acclaimed novel Invisible Man. The book’s narrator was lauded as a complex yet universal black protagonist, recounting his life with constant intellectual reflection, emotional insight, and, of course, humor. Expelled from an all-black university and sent to New York to find work, he buys a buttered yam and eats it on the streets of Harlem. Suddenly euphoric at publicly indulging in stereotypical “black” behavior, for which the narrator had been made to feel ashamed, he embraces the stereotype, declaring proudly, “I yam what I am!” Invisible Man, Ellison’s only novel to be published before his death, influenced African-American authors throughout the 20th century, including President Barack Obama’s Dreams From My Father. Comedically, Ellison elevated African-American folk humor, and was revolutionary in his ability to find comedy in the paradox between satirizing and fostering stereotypes that surrounded black comedy since Billy Kersands.

“I yam what I am” has been echoed throughout much of modern black stand-up, including David Chappelle’s chicken joke.

‘Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend’

“But square-cut or pear shape /

These rocks don’t loose their shape. /

Diamonds are a girl’s best friend.”

Dumb-blonde jokes can be traced back as far as the 18th century, but it was Marilyn Monroe’s portrayal of Lorelei Lee that cemented them in modern pop culture. During this big dance number, Monroe’s iconic look, bleached-blonde and adorned in a thick diamond choker with a tight bright-pink dress, creates the prototype for a dumb blonde. She needs to be flamboyantly feminine, and speak softly and vapidly. As she says in the movie, “I can be smart when it’s important, but most men don’t like it.” Monroe’s quick quips of feigned ignorance are supported by the groundedness of Dorothy Shaw, played by Jane Russell, in a rare-for-the-time female comedy duo. Helmed by Howard Hawks, a director famous for his “Hawksian” tough-talking woman, the movie demonstrates comedy through the actress’s use of sexual agency. Monroe’s femininity is not an object but a tool to get what she wants — famously, diamonds. The sheer size of Monroe’s performance defined this fundamentally American archetype. Without her, there would be no Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion, Cher in Clueless, or Elle Woods of Legally Blonde.

The Talking Mailbox

Mailbox: Be careful.

Woman: [Running backwards, screaming] Ahhhh!

[She returns and tries to put the letter in the mailbox]

Mailbox: Miss, don’t drop that letter in until I know where it’s going. Where you sending it to?

Woman: [Pulling the letter back] Are you kidding?

Mailbox: No, ma’am, this is the new service of the post office.

As long as there have been people to prank, there have been practical jokes, but it wasn’t until Candid Camera (which was developed out of the Candid Microphone radio show) that they became weaponized as a tool for big comedy. The show’s most famous prank involved a microphone, a loudspeaker, and a mailbox. As folks approached the mailbox with some letters, a voice that seemed to come from within would urgently accost them. It sounds pretty tame by today’s standards, but that’s because we’re used to pranks involving Justin Timberlake crying or Borat making fun of rodeo fans to their faces. But the show was a game-changer, eventually acting as a shorthand for whenever an incredulous person found themselves in a stressful situation. “Am I on Candid Camera?” people would ask for decades. It’s legacy, ironically, likely will outlive the mailbox.

The Ending

VLADIMIR: We’ll hang ourselves to-morrow. [Pause.] Unless Godot comes.

ESTRAGON: And if he comes?

VLADIMIR: We’ll be saved.

Vladimir takes off his hat, peers inside it, feels about inside it, shakes it, knocks on the crown, puts it on again.

ESTRAGON: Well? Shall we go?

VLADIMIR: Pull on your trousers.

ESTRAGON: What?

VLADIMIR: Pull on your trousers.

ESTRAGON: You want me to pull off my trousers?

VLADIMIR: Pull ON your trousers.

ESTRAGON: [realizing his trousers are down]. True.

He pulls up his trousers.

VLADIMIR: Well? Shall we go?

ESTRAGON: Yes, let’s go.

They do not move.

Specifically building off vaudevillian dialogue rhythms, Samuel Beckett’s absurdist masterpiece offered a window into what a deeper comedy could look like. The ending plays like a classic two-man ending, but with real doses of menace and existential angst. Waiting for Godot clearly led in the great comedies of menace by the likes of Harold Pinter and Edward Albee, but its influence on capital-C comedy was also tremendous. There is Godot in Ernie Kovacs’s disquieting absurdity, Michael O’Donoghue’s violent darkness, Andy Kaufman’s anti-comedy, and Woody Allen’s comedy of searching for meaning. However, more than anything, Vladimir and Estragon’s vacuous, intentionally aloof conversation instantly feels like a stripped-down version of what would become Seinfeld’s show about nothing. The ending, in particular, feels like it inspired Larry David’s rule of “no hugging, no learning,” especially since Beckett explicitly avoided explaining any underlying meaning to his work. Now, over 60 years later, you can see dashes of Godot in shows like Atlanta, The Good Place, The Eric Andre Show, and most other shows on Adult Swim as well.

“Ev’ry Street’s a Boulevard in Old New York”

Dean Martin: I love New York.

[Martin passes the microphone to Lewis.]

Jerry Lewis: I love New York.

[Martin takes the microphone back.]

Dean Martin: All the streets in the city are one in the same.

So I leave it to you …

[Lewis impersonates the faces Martin makes while singing]

what’s in a naaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaame?

The post–World War II nightclub era was glamorous and glorious, and there isn’t another example of that moment as fabled and folkloric as Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis’s sold-out run at New York’s famed Copacabana. It has been described as a sensation on par with the Beatles at Liverpool’s Cavern. Their power as a double act shook up the world of entertainment and catapulted them to stardom on television, on records, and in movies. Their signature song-and-dance routine “Ev’ry Street’s a Boulevard in Old New York” was featured on their hit TV variety series The Colgate Comedy Hour and in their feature film Living It Up. But here, even in this poorly shot peek at a 1954 performance at the Copa, the excitement of seeing the performers live in a nightclub and the affection that defined their act is palpable. Two years later, Martin and Lewis went their separate ways in one of entertainment’s most notoriously acrimonious splits.

Straight to the Moon!

Alice: There’s only one thing, Ralph, that’s missing from my Disneyland, only one thing: the world of tomorrow. I have nothing from the world of tomorrow.

Ralph: You want the world of tomorrow, Alice? You want the world of tomorrow? I’ll give you the world of tomorrow. [Making a fist] You’re going to the moon!

Alice: Har-har-har-dee-har-har.

There is no phrase more closely associated with The Honeymooners than Ralph Kramden finding himself at a loss for words with his wife, Alice, generally because she has made a biting comment about him, and then threatening to “send her to the moon.” Domestic abuse is in itself not funny, not in 2017 or 1955, but here Ralph isn’t expressing a threat so much as frustration. The viewer knows there is no one Ralph loves more than Alice, and that he’d never actually lay a hand on her. The key is the joke doesn’t end there, but in Alice’s dismissing him. Ralph’s fist-making is the result of him losing the fight. The joke is always on him. The Honeymooners didn’t sugarcoat relationships, allowing audiences to see that even though a couple may fight, if there’s truly love there, they can make it through anything. Every sitcom-couple fight, whether it’s between Archie and Edith Bunker or Homer and Marge Simpson or Louis and Jessica Huang, has its roots here.

Phonetic Punctuation

A period sounds like this: puttt.

A dash: fsssssssh.

An exclamation mark is a vertical dash with a period underneath: fsssssssh putt.

A Danish pianist-comedian who performed into his ’90s, Borge delivered a gentle, playful form of stand-up that was mostly about classical music. He performed in an era when concertgoing was more commonplace, and thus page turners standing at the piano, or opera singers who have to come in on cue, were easy to parody. His most famous routine, though, involved no music: He’d take out a book onstage and read a few paragraphs while speaking and pantomiming the punctuation marks: a fsss-puttt for each exclamation point as he drew it in the air, a click in his cheek for each comma, accelerating as the passage went on. You can hear his cerebral approach in Tom Lehrer’s more biting songs, and perhaps Mark Russell’s more political ones; you can certainly see his literate quirks propagated throughout the Ira Glass–”Shouts & Murmurs”–”Wait Wait…Don’t Tell Me!” universe. A funny-punctuation column, in the right hands, would fit perfectly well in, say, the next issue of McSweeney’s.

Slow Talkers of America

Bob: I am … The president … and recording…—

Ray: Secretary.

Bob: Secretary… of the S … T … O … A … The …—

Ray: What does that stand for?

Bob: Slow … Talkers … of America …

When radiomen Ray Goulding and Bob Elliott (father to Chris; grandfather of Abby) bantered on the air together for the first time in the mid-’40s, there was no way they could have known their budding partnership would last five decades. The gentle, patient comedy of Bob & Ray was about both medium and message: It used the burgeoning entertainments of radio and TV to poke fun at the programming and the personalities behind the media — hapless reporters, lackluster sports announcers, and marginal celebrities of every kind. One of their most recognizable bits, which they started doing in 1957, features Bob as a spokesperson for an organization called the Slow Talkers of America, and an exasperated Ray finishing each and every one of his painfully predictable sentences. The characterizations and pacing behind the Slow Talker bit make it a crystalline example of what makes their comedy great. This sort of playing with the conventions of double-act comedy is a clear influence on Saturday Night Live and the big comedy deconstructionists of the ’70s and ’80s — Albert Brooks, Steve Martin, David Letterman, and Andy Kaufman.

The Fudge-Cake-Powered Moon Rocket

Bullwinkle: [Holding a cake] Here’s the latest one, Rocky.

Rocky: Will it make a good rocket fuel, Bullwinkle?

Bullwinkle: Well, I don’t know but it sure will make a dandy lunch.

The late-’50s, early-’60s animated adventure parody from Jay Ward — the producer of pioneering cartoon show Crusader Rabbit — dazzled with its zany plotlines and crackerjack voice-overs, even if the movements of its anthropomorphic animals remained rudimentary. While the anthology series included segments featuring clueless Mountie Dudley Do-Right and many others, the chipper squirrel Rocky and dopey moose Bullwinkle remained in the spotlight. The show’s trademarks included melodramatic cliffhangers, intentionally bad puns, and knowing jokes that poked holes in the fourth wall (“I’m worried, Bullwinkle.” “The ratings of the show down again?”). From the first story arc, “Jet Fuel Formula,” the show dared Americans to laugh at their Cold War fears, as Bullwinkle’s prized recipe for fudge cake creates a rocket fuel the Russian baddies Boris Badenov and Natasha Fatale want to steal. Not only does the U.S. government make a grab for it, so do men from the moon — who’d rather not have to deal with tourists at all. A great combination of high and low, stupid and smart, R&B paved the way for people like Matt Groening (who gives characters the middle initial J. in honor of Ward).

One Leg Too Few

Casting Agent: Mr. Spiggott — you are, I believe, auditioning for the part of Tarzan.

Mr. Spiggott: Right.

Casting Agent: Now, Mr Spiggott, I couldn’t help noticing — almost at once — that you are a one-legged person.

Mr. Spiggott: You noticed that?

Casting Agent: I noticed that, Mr Spiggott. When you have been in the business as long as I have, you come to notice these little things almost instinctively.

Peter Cook, Dudley Moore, Alan Bennett, and Jonathan Miller’s collaboration is credited as the origin of the 1960s satire boom and the birth of contemporary British humor. The revue became a sensation in the U.K. after debuting at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in 1960. In 1962, the group’s absurd, deeply ironic comedy made its mark on America with a run on Broadway. Their most well-known sketch, “One Leg Too Few,” commands the audience to buy into the ridiculous premise of a one-legged man wanting to audition for one of cinema’s most athletic and agile characters, Tarzan. The joke hinges on Moore’s physicality, with him hopping up and down on the single appendage, each bounce emphasizing the shortcoming, and Cook’s pleading politeness, as he tries to offer a small glimmer of hope to the auditioning actor. Still, both actors play the situation entirely straight, opposed to the over-the-top performances seen in sketch comedy at the time. It was a complete revelation and seminal to the evolution of the form. Their act was a tremendous influence on Monty Python and Peter Sellers. It was so seminal to Lorne Michaels that not only did he have Dudley and Cook host an episode of Saturday Night Live in its first season, he had them reprise the sketch.

‘The Country Was in Peril; He Was Jeopardizing His Traditional Rights of Freedom and Independence by Daring to Exercise Them.’

Author Joseph Heller’s time as a bombardier in World War II did a number on him, in a curiously literal way. In Heller’s satire Catch-22, doubting pilot Captain John Yossarian encounters backwards officers such as Major Major Major Major — who only holds office hours when he is away — and does all that he can to escape the perils of combat. When Yossarian pleads insanity, he learns about the dastardly, no-win principle known as Catch-22: Only mentally unstable men would fly missions capable of harming themselves and others, but anyone who pleads insanity (in hopes of avoiding these duties) is clearly sane. Either way, mad or mentally sound, a soldier must obey. This idea lies at the heart of the novel’s topsy-turvy world, as is reflected in this joke told by the book’s signature third-person omniscient narrator, and at the center of Catch-22’s assault on the military-industrial complex and the God that made it. The book is considered one of the greatest literary works of the 20th century and spoke directly to political satirists of every stripe. Lewis Black, Armando Iannucci, and Heller’s pal Christopher Buckley are among those who have cited its influence.

‘Declaration of Independence’

Jefferson: Come on and put your name on the dotted line

Franklin: I gotta be particular what I sign

Jefferson: It’s just a piece of paper

Franklin: Just a piece of paper, that’s what you say

Jefferson: Come on and put your signature on the list

Franklin: It looks to have a very subversive twist

Jefferson: How silly to assume it

Won’t you nom de plume it today?

You’re so skittish

Who possibly could care, if you do?

Franklin: The Un-British Activities Committee, that’s who.

For its first few years, the potential of the young format of the comedy LP (long-playing record) was still largely unexplored. Most albums being released were merely recordings of comedians performing their routines before live nightclub audiences. Then, in 1961, recording artist and self-described “guerrilla satirist” Stan Freberg did something unheard of. He produced a lavish musical-comedy extravaganza for the ear that was a satirical journey through American history. The Los Angeles Times would later describe it as “The Sgt. Pepper of comedy albums” and Time magazine heralded it as “arguably the best comedy album ever made.” Beyond its impressive scope and scale, the album brilliantly employs the perspective of contemporary culture to bring a modernity to the revisionist characterizations of our founding fathers (a clear influence on the National Lampoon and Saturday Night Live). A prime example is the Declaration of Independence track wherein an earnest Thomas Jefferson presses a recalcitrant Benjamin Franklin to sign his “petition.” In his resistance, Franklin expresses concern about it sounding “pinko” and protesting, “I’m not gonna spend the rest of my life writing in Europe!” The clear allusion to the long-standing red scare in the United States and the ongoing blacklisting of artists with suspected communist ties by likening modern-day political activism to the Revolutionary War was itself revolutionary.

The Nairobi Trio

Ernie Kovacs was one of comedy’s earliest experimentalists, abstracting humor to its barest or at least weirdest elements. His masterpiece was the Nairobi Trio, a recurring bit in which Kovacs and two guests in gorilla masks and derby hats (often one would be a celebrity like Frank Sinatra, but you couldn’t necessarily tell because of the masks) doing a mechanical, nonsensical routine choreographed to 20th-century composer Robert Maxwell’s goofy “Solfeggio.” What further distinguished Kovacs’s work was it was shot without a live audience, creating a sort of deadpan randomness that would play best for those watching it at home. It is as weird as it sounds. You would think Kovacs was ahead of his time, but this bit was a sensation. Kovacs created a strange flavor of comedy that you can see everywhere now, from Monty Python to SNL to Conan O’Brien. It’s especially hard to imagine any Adult Swim show existing without Kovacs’s band of gorillas.

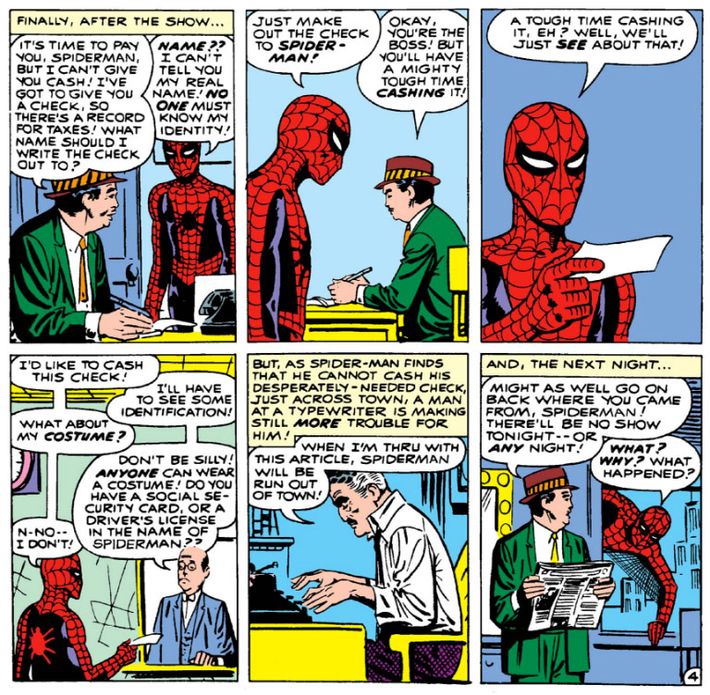

Spider-Man Can’t Cash a Check

Spider-Man: I’d like to cash this check!

Bank Teller: I’ll have to see some identification!

Spider-Man: What about my costume?

Bank Teller: Don’t be silly! Anyone can wear a costume! Do you have a social security card, or a driver’s license in the name of Spider-Man??

Prior to the early 1960s, superheroes were, for the most part, unrelatable dullards. Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and Captain America were wholly exempt from the concerns of workaday human beings, opting to shout dull platitudes about justice before returning to their pristine lairs for peaceful contemplation of future world-saving. If money were ever mentioned, it was certainly never an issue for these do-gooders. Thank goodness, then, for the advent of Spider-Man, superhero fiction’s first realistically lower-middle-class icon. Writer Stan Lee and writer-artist Steve Ditko designed the wall-crawler to be a neurotic and put-upon teenager who’s abruptly granted powers, then finds them to be as much a burden as a gift. After all, crime-stopping is an unpaid enterprise, and the kid needs to take care of his elderly aunt and put food on her table, for chrissakes. In the first issue of Spidey’s solo series, we get a delightful moment in which his heroic ambitions and financial needs run at cross purposes. He reluctantly shows off his powers in a live show in order to earn some much-needed dough, but when he gets the check, he realizes he can’t give away his secret identity and asks for it to be made out to Spider-Man. Upon arriving at the bank, he’s informed that, no, you can’t cash a check if you’re wearing a mask. The gag is a clever subversion of superhero infallibility, producing both laughs and renewed interest in the genre’s potential — all while showing that no good deed goes unpunished, even for a selfless metahuman. Plus, Ditko’s image of a fully costumed Spider-Man standing in line at a bank like a total zhlub is just flat-out wonderful. These days, Marvel’s superhero films are among the most-watched comedies of every year — sure, the punching and blasting is fun, but people really come to see these eminently human goofballs get into wacky, quippy situations with one another. With this joke, the concept of the quirkily relatable superhuman swung into comedy, and it’s been stuck there ever since.

‘Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah (A Letter From Camp)

“Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah,

Here I am at Camp Granada /

Camp is very entertaining /

And they say we’ll have some fun if it stops raining.”

Along with Elvis Presley, Ray Charles, and West Side Story, Allan Sherman’s LP My Son, the Folk Singer was among the best-selling records of 1962. Sherman, a portly Jewish TV-game-show producer, sold over a million copies of his debut collection of gentle (but definitely not gentile) Yiddish-inflected song parodies, establishing him as one of the giants of the era’s musical-comedy record boom, alongside Tom Lehrer and Stan Freberg. Less than a year later, Sherman followed it up with his third album, My Son, the Nut, which would include his best-known song, “Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah (A Letter From Camp.)” Set to the familiar tune of Ponchielli’s “Dance of the Hours,” the song is a desperate plea from a child at summer camp to his parents, enumerating the atrocities he is supposedly enduring. The song went on to win the 1963 Grammy for a comedy record and would remain a perennial favorite on the “Dr. Demento” radio show for decades — long after Sherman’s untimely passing in 1973 at the age of 48. Essential to his development, Weird Al Yankovic included the image of an Allan Sherman LP on the cover of his own debut album. “Hello Muddah” would go on to find another audience in the ’90s, when it both partly inspired the plot of a Simpsons episode and was played as a joke in another one three seasons later.

‘Will the People in the Cheaper Seats Clap Your Hands? And the Rest of You, If You’d Just Rattle Your Jewelry.’

Pop stars had made quips onstage before, and some, like the Rat Pack, had full routines worked into their performances. The Beatles, who quickly garnered Marx Brothers comparisons, were different. Perhaps the most famous example was at the Royal Variety Performance, with the Queen Mother and Princess Margaret in attendance. Before performing their closer, John Lennon made the most out of the situation and uttered the immortal words above. Just as notable as the joke was the way it was delivered, with John almost ducking out of the way after delivering it, giving a sheepish thumbs-up to the camera and a smile to his bandmates. The quip would be among the first coverage the Beatles’ would receive in America, with Time using it in an article entitled “The New Madness” and a CBS reporter noting, “Some say they are the authentic voice of the proletariat.” The Beatles went on to become the biggest band of the 20th century and the influence of their point of view and attitude would extend beyond music to every comedic, cute asshole who gives you the finger with a childlike grin.

‘Hi! We’re Mr. and Mrs. Peters!’

Laura Petrie: Rob, there are no series of tests in the world that are going to convince me that is not our baby.

Rob Petrie: Oh, honey, I don’t blame you. You can’t face the facts. Poor kid.

[Doorbell rings]

Laura: Oh, Rob!

Rob Petrie: Well, honey, that’s probably the Peters now. Brace yourself.

Laura: Rob, nobody’s taking this baby. Do you hear me? Nobody!

Rob Petrie: Laura, I think it would be better if you went to your room. I can handle it.

Laura: I am staying right here.

[Rob opens the door]

Mr. Peters: “Hi! We’re Mr. and Mrs. Peters!”

Rob Petrie: Uh … come in.

[Mr. and Mrs. Peters walk in and Rob sees they are black]

This is actually the single joke the entire episode had been building toward for 20 minutes. Rob and Laura have just brought home their newborn baby, Richie. Rob, through a few moments of miscommunication, convinces himself that they have brought home the baby of the Peters, the couple in the room next door. Eventually, Rob convinces the Peters to come over, with them not knowing that they’re about to walk into a confrontation with Rob. That is until they step into the room and the audience sees that they are a black couple. CBS was initially nervous about offending African-American audiences, but creator Carl Reiner argued that the joke wasn’t on the Peters, as later in the episode Rob remarks that the Peters’ kid has straight-A’s while Richie is nothing but mediocre — a subversive comment at the time. This ability to execute an episode-length joke that is so specifically rooted in character and is also socially conscious highlights the level of quality and sophistication The Dick Van Dyke Show brought to the sitcom genre at the time. We take for granted now that a sitcom can be an auteur-driven, high-brow piece of art, but before Carl Reiner introduced the Petries to America it was mostly seen as discardable, lighter fare. The Dick Van Dyke Show was a seismic step forward.

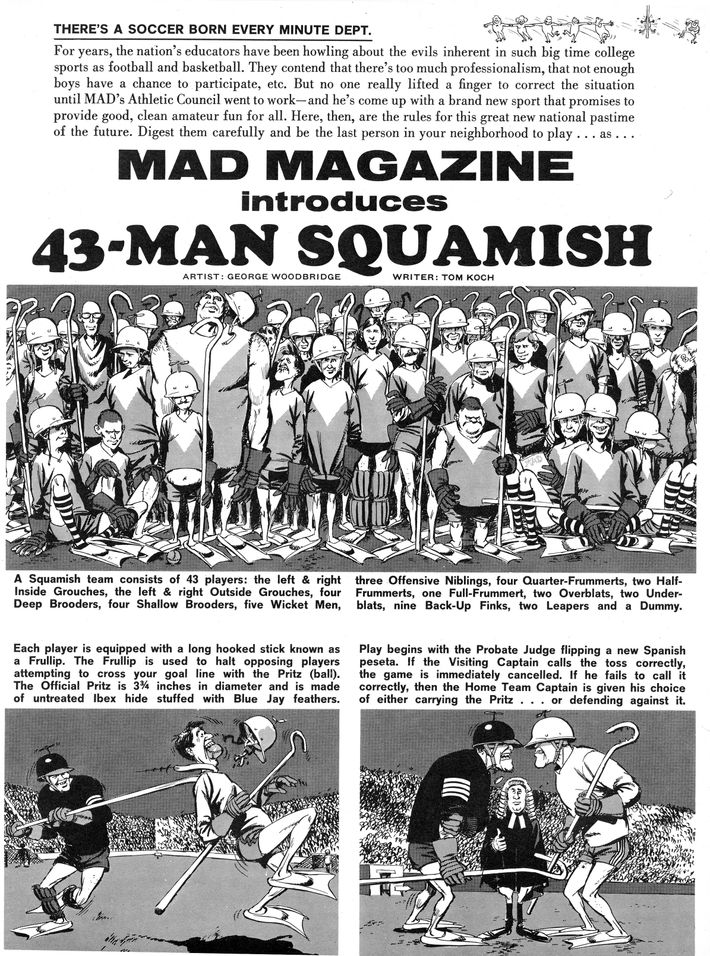

43-Man Squamish

“Everyone is lying to you, including magazines. Think for yourself. Question authority” is the editorial mantra for the famed Mad magazine. This mentality has aided in the zine’s ability to parody everything in American culture. Originally an EC comic, editor Harvey Kurtzman and publisher William Gaines founded the magazine in 1952. Tom Koch, who had worked with Bob and Ray, conceived of the legendary “43-Man Squamish,” and George Woodbridge illustrated it. Published in Issue No. 95, June 1965, the three pages of detailed drawings consisted of images of team members, the pentagon field, and even the National Squamish Rule Committee. It also listed all the absurd rules such as, “In the event of a disagreement between the officials, a final decision is left up to the spectator who left his car in the parking lot with the lights on and the motor running.” A reaction article on the concocted collegiate sport appeared two issues later. Readers wrote letters into the magazine with pictures of their teams. One stated they were undefeated champs due to their being the only team in Western Canada. What started as silly illustrations captioned with non sequitur regulations turned into a subversive achievement. It is Mad at the height of its powers: absurd, dumb, silly, ridiculous. Hard to imagine Weird Al, The Simpsons, or The Onion without it.

‘I’m Perfect’

“[Sidling up to a man in the audience] You’re dying to touch me, aren’t you, you son of a gun? Come on, I’ll give you one little touch. Come on, hurry up, one little touch. Ah [throwing his hand away from her]! An animal. That’s what you are — an animal.”

Early comediennes couldn’t rely on jokes alone, and much like today, a woman’s appearance had a big effect on how audiences interpreted her act. Phyllis Diller pioneered women’s stand-up with the help of outlandish makeup, dresses, and wigs to make fun of herself. Joan Rivers picked up the self-deprecating torch, but did so as an attractive, thin, and well-put-together lady. Rivers’s contemporary Totie Fields struck a balance that would have a lasting impact on women in comedy: She made fun of herself — her actual self, overweight and short at only four-foot-eleven — with the honesty and self-satisfied confidence of a female Don Rickles. A bawdy, no-nonsense broad who thrived in nightclubs as much as she did in her many Ed Sullivan Show appearances, Fields paved the way for women like Roseanne Barr, Lisa Lampanelli, and Melissa McCarthy.

Little Notes

Oscar Madison: Everything you do irritates me. And when you’re not here the things I know you’re going to do when you come in irritate me. You leave me little notes on my pillow. I told you a hundred times, I can’t stand little notes on my pillow. ‘We’re all out of Corn Flakes, F.U.’ It took me three hours to figure out F.U. meant Felix Unger.

Neil Simon began his career as a television writer for Sid Caesar and went on to become the most lauded and prolific comedy playwright and screenwriter of his generation. After his first Broadway plays Come Blow Your Horn and Barefoot in the Park opened to great acclaim, Simon hit the mother lode with the definitive buddy comedy about two roommates. One is a fastidious neat freak. The other is a slob. The Odd Couple premiered on Broadway directed by Mike Nichols in 1965, starring Walter Matthau and Art Carney, and was an immediate smash, winning Tony Awards for Simon, Nichols, and Matthau. The subsequent 1968 feature-film version created the greatest showcase for one of the cinema’s most adored occasional comedy teams of all time: Matthau and Jack Lemmon. The film was also a huge success, leading to the ongoing adventures of Felix and Oscar in the hit TV-series adaptation starring Tony Randall and Jack Klugman. Three inspired incarnations of a simple but brilliant idea that could be boiled down to this one rant. Creating a deeper version of the classic duo, Simon created a template that has continuously been used in TV and movies ever since.

Pat Paulsen for President

“I want to be elected by the people, for the people, and in spite of the people.”

In the late ’60s, The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour offered a home to comedy’s counterculture on a medium defined by being mainstream, featuring a range of politically engaged celebrity and musical guests and enlisting remarkable writers, including Albert Brooks, Steve Martin, and Don Novello. When the brothers wanted to parody U.S. political elections, they asked San Francisco comedian Pat Paulsen because of his deadpan delivery. The comic ran under the Straight Talking American Government Party, otherwise known as the STAG Party, and his slogans didn’t mess around: “United We Sit,” “We Can Be Decisive, Probably,” and “If Elected, I Will Win.” His run revealed the power of satire when done from inside the process and paved the way for Stephen Colbert’s similar run for president 40 years later. When Paulsen was older, he expressed some guilt about the false campaign, noting that he took votes from Hubert Humphrey in his close race against Richard Nixon. The fact that he got votes demonstrates the power of comedians playing politics.

‘Sock it to … Meee?’

Somewhere, someone is blaming comedian-hosts Dan Rowan and Dick Martin for Watergate. And while there’s no direct correlation there, it’s true that their fast-paced and slightly scandalous NBC sketch show Laugh-In provided Richard Nixon with a cameo that just might have gotten him elected. After the Great Debate sunk Tricky Dick’s chances against John F. Kennedy in 1960, he was eager for chances to appear lighthearted and likable on TV, and told writer Paul Keyes he’d pop in among the show’s short skirts and psychedelic backdrops. In his brief appearance, Nixon manages to turn toward the camera and say the Laugh-In catchphrase, but not without making it into an awkward, labored question. Still, the effort was enough to show the nation he wasn’t too wooden or buttoned-up to enjoy a bit of outrageous fun — and he was elected two months later. It’s hard to think Barack Obama would’ve traded jabs with Zach Galifianakis on Between Two Ferns, Donald Trump would’ve let Jimmy Fallon tousle his hair, and SNL would become an essential campaign stop without Nixon’s cameo. It encouraged politicians to be entertainers and comedians to sometimes make comedy with the people they are usually making comedy about.

‘PUNCH LINE’

“PUNCH LINE

“So [said the doctor]. Now vee may perhaps to begin. Yes?”

American-Jewish shtick and American-Jewish literature had mixed with each other for decades, but has there ever been a higher-achieving mix? A novel that starts funny and angry and gets funnier and angrier, building to an actual punch line, explicitly labeled PUNCH LINE. Thereafter, the two idioms were fused, and you’d never have seen Larry David clearing his throat in an extended sex joke, or Jonathan Safran Foer writing in jokey Eastern European dialect, without it.

Dead Parrot

Mr. Praline: Look, I took the liberty of examining that parrot, and I discovered the only reason that it had been sitting on its perch in the first place was that it had been nailed there.

Shop Owner: Well, of course it was nailed there. Otherwise, it would have nuzzled up to those bars, and VOOM!

Mr. Praline: Look, matey, this parrot wouldn’t “voom” if I put 4,000 volts through it. It’s bleedin’ demised!

Shop Owner: It’s not. It’s pining.

Mr. Praline: It’s not pining. It’s passed on. This parrot is no more. It has ceased to be. It’s expired and gone to meet its maker. This is a late parrot. It’s a stiff. Bereft of life, it rests in peace. If you hadn’t nailed it to the perch, it would be pushing up the daisies. It’s rung down the curtain and joined the choir invisible. This is an EX-parrot!

The Oxford- and Cambridge-educated six-member comedy troupe stood on the shoulders of fellow British comedy collectives the Goons and Beyond the Fringe to become the first and most significant act to cross over to mainstream American consciousness. Considering the amount and impact of their work, picking only one joke is nearly impossible, but John Cleese’s incensed rant about a dead parrot to Palin’s gleefully dishonest shopkeeper is probably their most celebrated. The sketch masterfully balances its surreal, dark, absurd premise by establishing fully realized characters with a clear conflict. As a result, it has gone on to be a Rosetta Stone for modern sketch writing, endlessly studied and rewatched by each new generation of comedians. Its influence was quickly felt on the early years of Saturday Night Live, as well as just about every other sketch show since. Bob Odenkirk has stated that Mr. Show With Bob and David was an attempt to do an American version of Flying Circus.

‘The Parts That Were Left Out of the Kennedy Book’

She corroborated Gore Vidal’s story about Lyndon Johnson, continuing: “That man was crouching over the corpse, no longer chuckling but breathing hard and moving his body rhythmically. At first I thought he must be performing some mysterious symbolic rite he’d learned from Mexicans or Indians as a boy. And then I realized — there is only one way to say this — he was literally fucking my husband in the throat. In the bullet wound in the front of his throat.”

Just before William Manchester published The Death of a President, his 1967 account of the Kennedy assassination, Jackie Kennedy’s representatives read the manuscript and demanded a few pages be pulled. Paul Krassner, a Mad alumnus and founder of the Yippie movement who’d grown up to start his own satirical magazine, The Realist, ran a fantastical, gleefully disgusting “account” of what they might have revealed. In Krassner’s purportedly deleted scene, set aboard Air Force One as Lyndon Johnson flew back to Washington with JFK’s body, Jackie had walked in on the new president as he had sexual intercourse with one of the corpse’s wounds. It was a spectacular example of the theory that if you offer such a whopper that the source cannot even acknowledge it with a denial, it will stand unchallenged. Radicals and conspiracy theorists, from Infowars to the Sandy Hook Truthers to the birther movement, have learned that lesson very well. Along with John Waters, who to his credit filmed a reenactment of the assassination with Divine as Jackie Kennedy around the same time, The Realist’s issue 75 marks an early high-water mark for the comedy of bad taste.

The Devil Made Me Do It!

“She came in the house, she had the box. Rev saw it. Rev said, ‘What, another dress?’ He says, ‘This is ridiculous. Three dresses in a week! Another dress!’ And she tells him, ‘[With his hand on his hip, in Geraldine’s voice] I didn’t want to buy this dress. The devil made me buy this dress.’”

In a 1979 interview, Flip Wilson said that the turning point in his career was when a white friend gave him some very pointed advice that he shouldn’t think of being black as something to feel sorry about but something to be amazed by. “That’s when I realized how interesting being black is,” he told the interviewer. “Okay. They waiting to see a nigger who’s afraid or shy. No way, niggers is fun. Niggers is good!” As Mel Watkins writes in On the Real Side, the revelation “allowed him to reflect an uninhibited celebration of black life in his humor.” The most famous example of this was Geraldine, whom he first introduced in this masterful stand-up routine in which Wilson acts as the narrator, Geraldine, Rev, and the devil. Geraldine was a brassy woman who, to use the parlance of the time, was liberated. She was always confident and always ready to speak her mind. Many might not know Geraldine today, but even if you didn’t know she was the source, her catchphrases permeated the culture through every race: “When you’re hot you’re hot, when you’re not you’re not.” “What you see is what you get.” And of course, Geraldine’s excuse for when things went awry: “The devil made me do it.” Wilson parlayed the jokes’ success (The Devil Made Me Buy This Dress, the album the joke appeared on was a huge hit and won the Grammy) into The Flip Wilson Show, which was the first successful variety show to be hosted by an African-American. Geraldine became a sensation and a fixture of the series, with Wilson dressing in drag and usually seducing a famous male guest. In both his tremendous success and the richness of his characters, Wilson set the table for the black sitcom boom that would come a few years later.

‘This Your Truck?’

[Maude drives a battered green truck with a lone tree in the open bed through a toll booth without paying. Harold is in the passenger’s seat. A motorcycle officer witnesses this and pulls her over.]

Motorcycle Officer: License, lady?

Maude: I don’t have one. I don’t believe in them.

Motorcycle Officer: How long you been driving, lady?

Maude: About 45 minutes, wouldn’t you say, Harold? We were hoping to start sooner but you see

it’s rather hard to find a truck.

Motorcycle Officer: This your truck?

Maude: Oh no, I just took it.

The release of films such as The Graduate, Easy Rider, and Five Easy Pieces exemplified how the counterculture of the late 1960s and early 1970s crept into cinema comedy. But perhaps the most original and distinctive example of this existential oeuvre is Hal Ashby’s unexpected love story between a disaffected boy and an irrepressible elderly woman closing in on her 80th birthday. Before meeting Maude at the funeral of a man neither of them knew, Harold is seen stone-facedly pranking everyone he encounters with ingenious staged fake suicide attempts. But in Maude he meets his match who, in her joie de vivre, unrepentantly steals multiple cars, laughing in the face of propriety and authority. Theirs becomes a romance more shocking in its own subversive way than even the era’s Bonnie and Clyde. The roots of everything you love about Wes Anderson’s best work, especially in Rushmore, are firmly planted in Ashby’s visionary classic.

Divine Eats Dog Poop

Writer-director John Waters has always been drawn to the outrageous gesture, both as reaction to the clean-cut and composed America projected by ’50s media and as a way to indulge his own gleefully twisted fantasies. In the early, low-budget cult hit Pink Flamingos, the so-called “Pope of Trash” introduces Babs Johnson — portrayed by 300-pound Baltimorean drag queen Divine — who must fend off challengers to her title “Filthiest Person Alive.” The plot is minimal, but once the film’s foul parade of murder, nonconsensual chicken sex, and singing buttholes is nearly over, Babs steps forward to perform one final act of depravity. While the Patti Page ditty “(How Much Is That) Doggie in the Window” plays, Divine/Babs crouches down behind a shaggy gray poodle; she nabs the dog’s turd, pops it in her mouth, chomps down, and finally gives the camera a glistening, brown grin. Disgusting? Shocking? Funny? Yes to all of the above. Waters codified a mass camp style and used it as weapon against “good” taste, inspiring everyone from Matt Stone and Trey Parker to RuPaul, who had Waters on Drag Race, to the Jackass guys, who had Waters cameo in their second movie.

Maude’s Dilemma

Carol: Mother, I don’t understand your hesitancy. When they made it a law you were for it.

Maude: Of course, I wasn’t pregnant then!