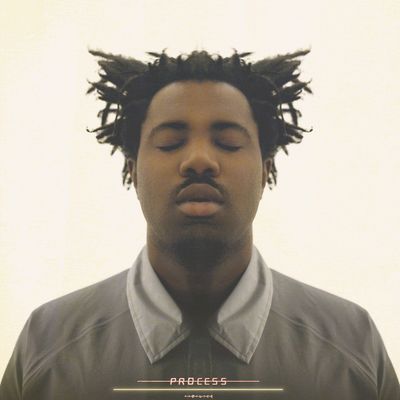

Over the last five years, British singer-producer Sampha Sisay has pieced together a catalogue of all-star collaborations that most artists won’t match in a lifetime — you might recognize his sullen, wraithlike vocals in Beyoncé’s “Mine,” Kanye West’s “Saint Pablo,” Frank Ocean’s “Alabama,” and Drake’s “Too Much” and “The Motion.” But like singer-songwriter James Fauntleroy — the storied Rihanna and Justin Timberlake collaborator casual fans of pop music would be excused not to know by face — Sampha has meanwhile seemed content to peck away at his solo work at his own pace, popping up on his producer buddy SBTRKT’s synthpop bangers and squeaking out a promising solo EP every few years.

As listeners who tend to experience an artist’s work beyond the veil of access, straining to discern character through a stream of news blasts and lyric sheets, we have a habit of devising simplistic answers to our unresolved curiosities — and yet, the reality often involves a series of advances and setbacks. You might mistake Sampha for a meticulous perfectionist or a satisfied sideman who doesn’t crave renown as a solo artist. In truth, the peculiar lulls in Sampha’s career are times he returned home to be by his mother’s side as she fought off stomach cancer. (This, after he lost his father to lung cancer as a child.) The disease returned a year after Sampha’s appearances on Beyoncé and Nothing Was the Same, and the singer suddenly found himself watching the light of his life flicker and fade at a point in his career when most ascendant 20-something musicians would be touring the world.

Once you have the facts, it’s tough to avoid hearing Process, Sampha’s oft-delayed debut solo album, as anything other than fallout from the loss of a parent. “Kora Sings” dives deep early on, as the singer moves from vagaries about family and inner strength to a crushing closing verse where he pleads: “You’ve been with me since the cradle / You’ve been with me, you’re my angel / Please don’t disappear.” “(No One Knows Me) Like the Piano” follows, sliding gracefully between a salute to the instrument Sampha’s father brought home one day and a remembrance of the love and warmth that time in his life represents. It sounds like a sweet love letter to family and music until you catch the chilling implication: Is he saying no one knows him like the piano in his mother’s home because everyone he has felt the same closeness to has passed away?

Grief is a powerful, mercurial force, a physical dilemma as much as a psychological one. Suddenly, there is negative space where there was once a body, and we fasten feelings onto objects in bereavement. However tiny, they satisfy a craving for the residue of a tangible connection that’s been rubbed out of our lives. Ever since a family member passed away two months back, I’ve had the funeral program on display next to a birthday card on a bookshelf opposite my bed. Fourth quarter was a tall order, as Chance the Rapper says in “Acid Rain.” One day in January, I was casually asked what the funeral program was still doing up there, and I didn’t know how to answer. I’ve shuffled the birthday card up front to keep from freaking anyone else out, but the obituary’s still there. I can’t bring myself to take it down.

Process is haunted by these realities of loss and mortality. When Sampha’s not reliving his real world adversities he’s being burned alive in opener “Plastic 100 C” and chased by an unseen death squad in “Blood on Me.” The love songs fixate on brokenness and inadequacy. It’s like a mirror image of A Seat at the Table, the Solange album Sampha contributed vocals and production to last year. Where Seat was an exercise in healing and acceptance, Process zooms in on suffering and diagnosis. There is no neat resolution to the personal unrest coursing through “Reverse Faults,” “Under,” and “Timmy’s Prayer,” a trio of wounded breakup cuts that fit together like a mini-album within the album. One ends in an apparent car crash, the other, underwater, and the third, buried alive.

Sampha’s turmoil also spills over into Process’ instrumentation, which pits the bedroom electronic bent of his Sundanza EP against the more baroque man-and-a-piano sounds of 2013’s Dual. The drums often feel live and programmed at once, like in “Kora Sings,” a kora and drum jam that sounds like house music as played by marching band, and “Blood on Me,” where an agile hi-hat and cowbell arrangement seems too perfect to be live. “Reverse,” “Under,” and “Timmy” all borrow pages from the Portishead book of kick-and-snare backbeats and wide open space. Process veers between a discomfiting nakedness and an overbearing largesse often at a moment’s notice, like a crying jag.

The truth about the grieving process is that there isn’t one. You don’t find yourself missing the departed less over time. You don’t get better at it through studious repetition, like with writing an essay or shooting a basketball. All you ever learn to do is hold onto something stable until your world stops spinning. Process is Sampha’s courage to be broken until that relief arrives.