Intentional poor taste is not a concept unique to comics, but comics have a unique ability to convey it in a way that makes you gasp. As cartoonist and theorist Art Spiegelman is fond of saying, the comics medium is built on a simplicity that can slip through your mental defenses and pierce your brain. We look at the textures and details of GoyaÔÇÖs Saturn Devouring His Son and nod our heads about its ghastliness, but we retch when we look at the cartoony dismemberment of guro manga (link NSFW, and the fact that I didnÔÇÖt need to say that about the Goya tells you all you need to know).

In an effective piece of bad-taste comics art, there are no excessive details and high-minded themes to act as buffers between you and the awfulness in front of you. If youÔÇÖre one of us whoÔÇÖs into that sort of thing, itÔÇÖs a kind of magic, capable of shocking you into equal parts delight and revulsion. In that regard, Joan Cornell├áÔÇÖs Zonzo is the most magical comic of the year ÔÇö and the latest entry in a proud, underappreciated tradition of sequential art designed to provoke both denouncements and surreptitious giggles.

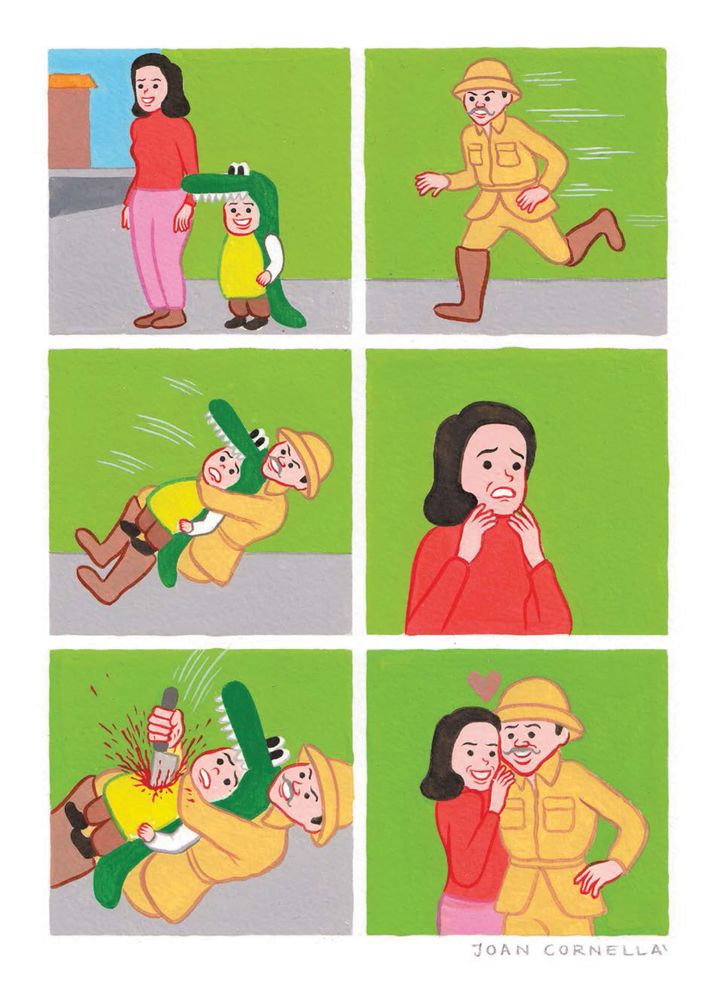

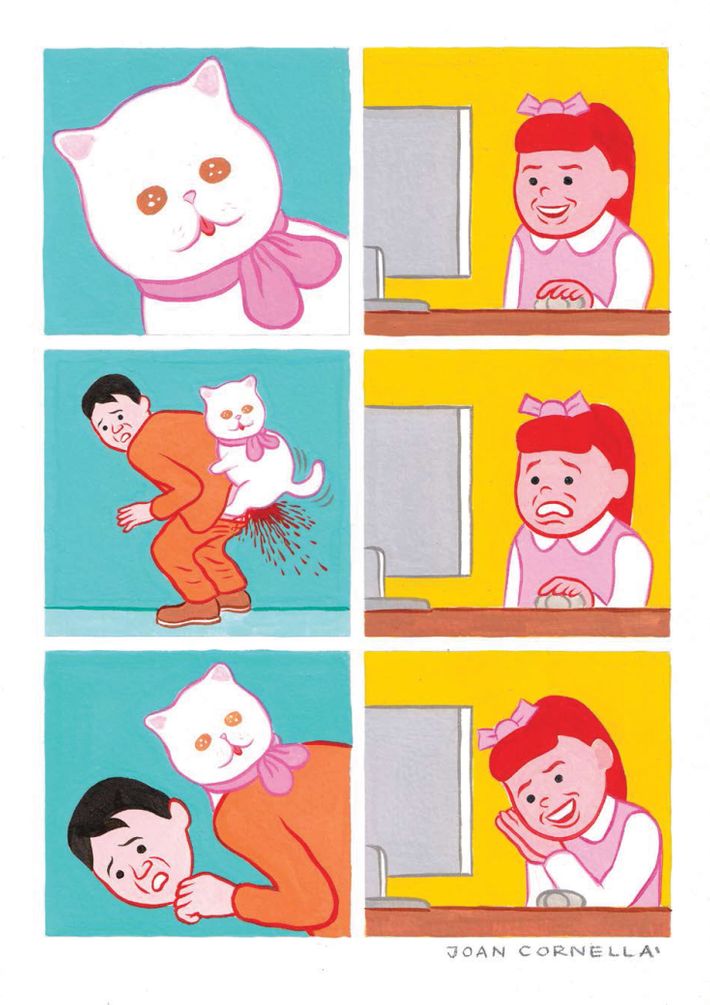

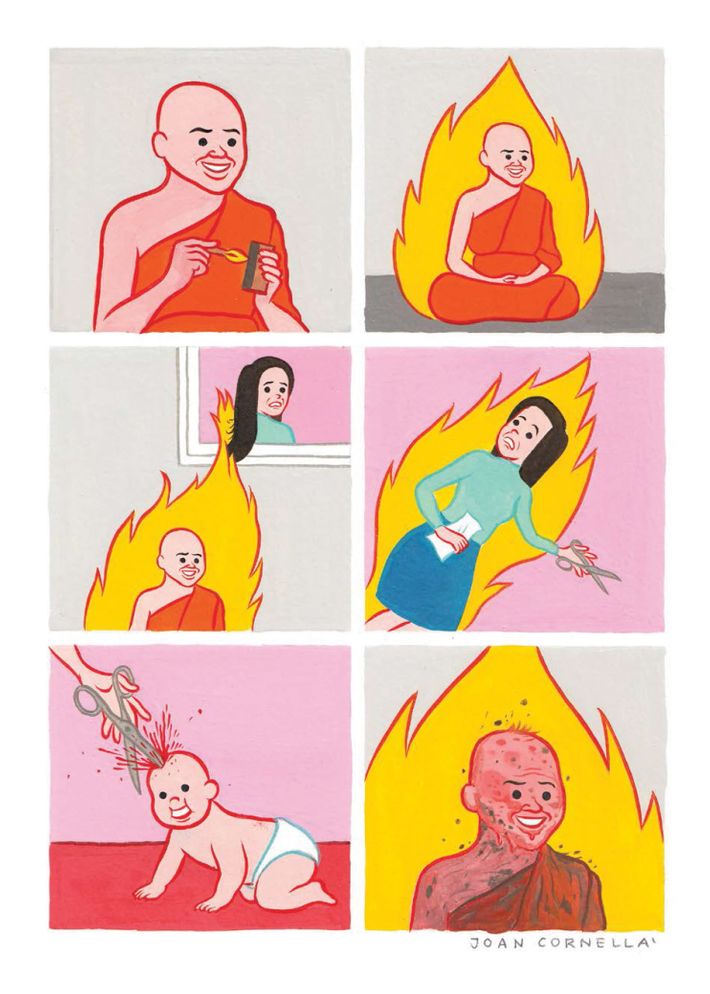

Zonzo is, in a word, appalling. ItÔÇÖs a slim compilation of dozens of the Spanish artistÔÇÖs wordless webcomics, most of them six panels long and all of them offensive in one way or another. A few are just well-executed off-color jokes, such as the one where a man surprises a young mother by pulling her chair away as she sits, causing her to mortally wound her swaddled infant by accidentally dropping it on the hard edge of a table and covering her with her childÔÇÖs blood; in the last panel, she and the waiter horrifyingly laugh at the wacky situation. Or the one where a big-game hunter kills a kid in an alligator costume in front of his mother (children dying in front of their mothers is a running motif in the book):

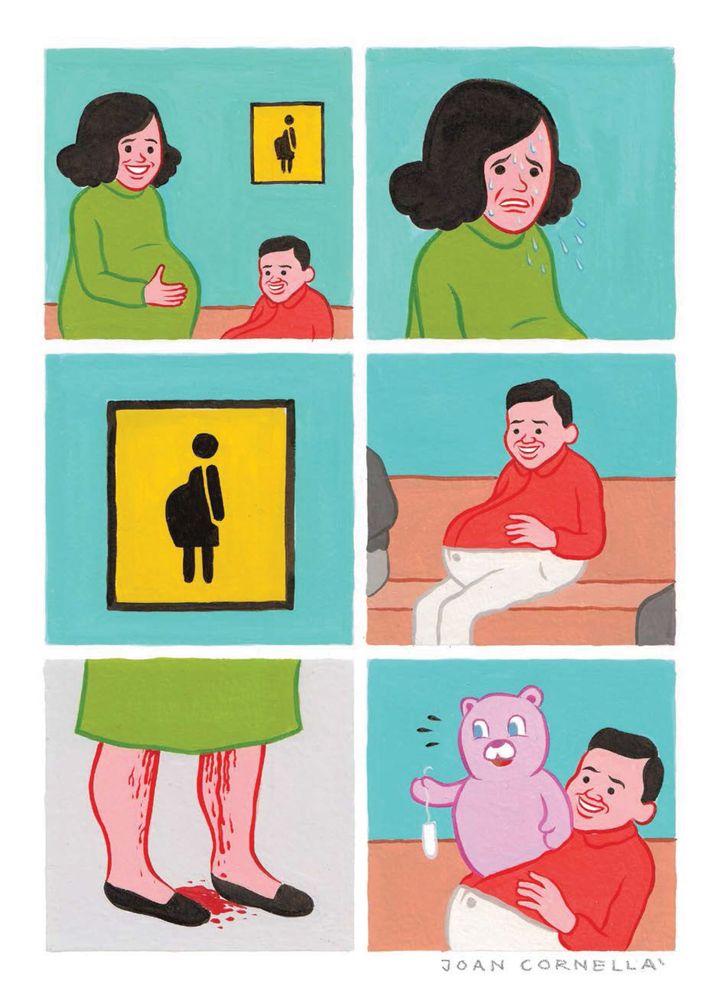

But most installments in Zonzo are way more abstract ÔÇö and, as a result, even more disturbing. A man is disappointed that a woman is grossed out by a head-size growth on his face, so he shoots her sonÔÇÖs skull off with an AK-47, then glues his growth onto the boyÔÇÖs body, paints a face on it, and dresses it up in a suit ÔÇö now the dead kidÔÇÖs corpse is his ersatz ventriloquist dummy, and the mother grins with delight. A pink elephant paints a swastika on a rainbow-colored sign being held by a topless man; the man then smiles as he shoots himself in the head and the remaining three panels are just a zoom-in on the elephantÔÇÖs giant eyes, for some reason. Such pieces are little masterpieces of the human imagination at its darkest, conveyed with bright pastels and beaming faces. Sometimes the smiles come from people; sometimes from, say, bears holding tampons, as is the case in this hard-to-describe strip:

Verbal descriptions, of course, donÔÇÖt do the comics justice (though ÔÇ£justiceÔÇØ feels like too cheery a word). To appreciate what Cornell├á has achieved, you have to bear witness to his blunt and unmistakable visuals, crafted with thick paints and subconsciously unsettling figure-outlines of red, rather than the traditional black. And the most terrifying aspect of any Cornell├á comic is his faces. The individuals in these little glimpses of hell never have the correct emotions for their situations, and the vividness of their inappropriate expressions sears your memory with horror.

These images have a rich set of comics-format precedents, many of them profoundly consequential in the history of the medium. There was a time when poor-taste comics were the industryÔÇÖs dominant mode. In the late 1940s and early ÔÇÖ50s, horror comics became a fevered trend among the youth of America, especially the flagship titles of publisher EC Comics: The Vault of Horror, The Haunt of Fear, and, most famously, Tales From the Crypt, which later served as the very loose inspiration for a series of film and television adaptations. ItÔÇÖs hard to overstate how popular these titles and their ilk were ÔÇö or how inventively gross.

Sure, there were hacks in the horror industry, but there were plenty of geniuses ÔÇö Jack Cole, Harvey Kurtzman, Bernard Krigstein, and Wally Wood, to name a few. The stories were daringly hideous, featuring all manner of severed limbs, makeshift abattoirs, and inventive deaths; and the covers were often even more hideous than the contents. They had a wide range of tones and subgenres, ranging from gorily comedic monster stories to salaciously brutal crime sagas. Perhaps most famous of them all was a 1947 tale by Cole entitled ÔÇ£Murder, Morphine, and Me,ÔÇØ in which a young woman drifts into junkie-dom and, at one point, has a nightmare about someone stabbing her in the eye with an ice pick ÔÇö an image that pierces the brain in more ways than one:

That eye-popping panel (an echo of a similarly infamous shot in Bu├▒uelÔÇÖs Un Chien Andalou) became inadvertently central in the history of American publishing. In 1954, a psychiatrist named Fredric Wertham published a best-selling book entitled Seduction of the Innocent (what a title!), which took aim at the depravity of comics art and its demoralizing influence on AmericaÔÇÖs youth. ColeÔÇÖs panel was a central example in the book, and the tomeÔÇÖs success triggered Senate hearings for comics publishers. To combat the moral panic, the industry set up a self-censorship rubric called the Comics Code and high-concept, bad-taste comics disappeared from the mainstream.

Luckily, they had a second life in unconventional avenues. The 1970s saw the rise of the Underground Comix movement, in which publishers like R. Crumb and Denis Kitchen would distribute to head shops their richly textured stories about massive sex organs and debased carnal acts. In the ÔÇÖ80s, U.K.-based publisher 2000 AD revolutionized the comics medium by allowing a generation of British writers and artists to indulge in brilliantly fetid cyberpunk ultraviolence.

Perhaps the most direct ancestor of Cornell├á emerged in the 1990s: a Chicagoan named Ivan Brunetti. Though Brunetti is now a classy cover artist for The New Yorker, back in the day, he published cult-classic examples of, as he put it in the subheading for one of his early collections, ÔÇ£horrible, horrible cartoons.ÔÇØ In books with titles like Schizo and Haw!, heÔÇÖd make pastiches of the Sunday funnies in which fathers sodomized their sons with harpoons, women severed their boyfriendsÔÇÖ penises with jagged knives, and infants blissed out while wearing their parentsÔÇÖ butt plugs.

ItÔÇÖs unsettling to even write such things down, much less say them out loud ÔÇö and that, in a way, is the point. ThereÔÇÖs something courageous in such refutation of conventional standards and practices, and something awe-inspiring that happens when the refutation is done with ideas that would never otherwise appear in your imagination. For better or worse, you canÔÇÖt forget them, and these straightforward, static images brand themselves on your brain more easily than the shifting pictures of a gross-out movie.

This bad-taste tradition has returned to the comic-book mainstream somewhat in recent decades. When a set of maverick Marvel Comics artists created their own company, Image, in 1992, they ignored the Comics Code and created hideous visions of viscera and brutality. One of them, SpawnÔÇÖs Todd McFarlane, was a veritable genius of unholy anatomy, building memorably disgusting creatures with names like Violator and Malebolgia. Later, Image imprint Wildstorm would gain infamy for publishing a superhero comic called The Authority, in which the Scottish writer/artist team of Mark Millar and Frank Quitely gave us clever send-ups of classic heroes who raped and murdered their way across the universe and a readerÔÇÖs psyche. Far from being fringe figures like Brunetti, Millar and Quitely have become two of the most successful creators in comic books. Poor, well-intentioned Fredric Wertham must be spinning in his grave.

The good doctor would have been even more horrified by the webcomics scene, where there are no barriers of quality, only the fuzzy ones of legality. A trip to 4chan or its more obscene knockoffs will punish a surfer with cartoony images of the worst sex and violence a person might dream up, but that stuff is usually too conceptually unambitious to merit any critical praise. Better by far is the work of inventive cartoonists like Nicholas Gurewitch, whose Perry Bible Fellowship is an ongoing masterwork of efficiently administered bad taste (e.g., a real-life game of Hangman and the Transformer who rearranges himself from his truck form while passengers are still inside).

And now thereÔÇÖs Zonzo, which is a wonderful reminder that comics art can still be uniquely and creatively obscene. Comic books are more globally lucrative than theyÔÇÖve ever been, with adaptations of them dominating box offices and TVs, and your average Avengers or Batman flick is understandably designed to be classy and inoffensive. Even the occasional filmic experiments in poor taste (Deadpool being the most successful example) have more in common with the frat-movie and sex-comedy tradition than horror comics or Ivan Brunetti. That is as it should be. A superhero can fly from the page to the screen, but Zonzo can only come alive in your sweaty palms, gazing at you unashamedly while you check to make sure no oneÔÇÖs looking at how much you enjoy such filth.