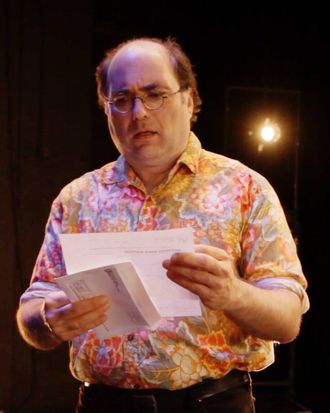

Writer and performer Josh KornbluthÔÇÖs new movie, Love & Taxes (directed by his brother Jacob), is a broad adaptation of his acclaimed monologue about growing up and joining the adult world: He had met his future wife (who became pregnant with their son) and made the fateful decision to confront the fact that he hadnÔÇÖt paid taxes in seven years. He was almost 40 when that happened, and it was agony. The child of vocal Communists ÔÇö as depicted in his monologue Red Diaper Baby, which was filmed ÔÇö Kornbluth seized on his fatherÔÇÖs disdain for giving anything to a repressive capitalist government as an excuse for being a major fuck-up.

Love & Taxes jumps between Kornbluth performing the monologue onstage and a full-on dramatization, which comes to an ugly head when he realizes that he owes the IRS (as well as his somewhat slippery accountant) more than $50,000 that he doesnÔÇÖt have. Apart from Kornbluth, the cast includes Harry Shearer as a Hollywood producer who options JoshÔÇÖs second monologue, Haiku Tunnel, and former secretary of Labor Robert Reich as a respected Washington tax attorney who tells Josh heÔÇÖs a pisher.

I canÔÇÖt write an objective review of the movie because IÔÇÖve known Josh for 35 years. We were acquainted when he was a copy editor at the Boston Phoenix and I was a third-string theater critic. But I had no inkling of his gifts as a performer until years later ÔÇö 1987, to be exact ÔÇö when I was visiting San Francisco and went to see his first show, Josh KornbluthÔÇÖs Daily World. I was a few minutes late and had opened the door of the theater before an usher appeared to ask for my ticket. When I entered a few seconds later, the entire audience said, in unison, ÔÇ£Hi, David!ÔÇØ I felt welcome.

In place of a review, then, I decided to use the opening of Love & Taxes as occasion to talk with Josh not just about the movie but also his start as a monologist. Nowadays, we have the Moth and other wonderful storytelling venues. But there werent many people in the 80s who walked onstage and simply told stories based on their own lives. There was the late Spalding Gray and  that was about it. So well start there.

Was Spalding Gray an influence?

The biggest. But I hadnt heard of him or the autobiographical monologue form he created until  Well, it was a weird confluence of events. In my 20s I thought I was going to spend my life as a copy editor. But about a week after my fathers death in 1983, I started messing up 

What was the nature of those errors?

It was an unusual way to fuck it up. I stood next to the speakers at a Violent Femmes concert and got ear damage, a ringing that turned out to be permanent ÔÇö tinnitus. And the screens that we used at the Phoenix gave out this high tone that to me was assaultive. But no one else heard it. People were, like, ÔÇ£Yeah, right, it has to be psychosomatic. Obviously you donÔÇÖt want to do this job.ÔÇØ I started coming in later and later. I couldnÔÇÖt even go into the corridor with all the computers ÔÇö ÔÇ£type alleyÔÇØÔÇö because my head felt like it was going to explode, like some evil Cronenberg thing. One time I just screamed in the middle of the newsroom and an editor walked me out of the building. ThatÔÇÖs when I thought I should pursue something else, because, you know, all copyediting would involve screens.

I tried to be a stand-up comic at an open mic night but realized the set was about two hours too short for me. It wasnÔÇÖt a good time. I was working as a secretary at MIT and living in a closet in the biology department because I was way behind on my rent in the apartment I shared with two people in Allston. Then my friend Scott Rosenberg, who was a theater critic at the Phoenix, invited me to see Spalding at the Brattle in Cambridge. IÔÇÖd never heard of him, but it was a fairly short walk away and free, so I went.

And ?

It was a ÔÇ£EurekaÔÇØ moment. The show was Sex and Death to the Age 14, which was six early monologues. I was entranced, I was moved, I was delighted both by Spalding and the audience, because of how they were paying attention, as if someone were reading a great novella. The way he calibrated his irony ÔÇö it was exquisite. I walked out thinking I would like to do this and also knowing it was crazy, because I started reading about Spalding and buying his books and learned heÔÇÖd been a straight actor and had done experimental stuff with Elizabeth LeCompte and others. I donÔÇÖt have any of that background. But I thought if he could make a story out of his upbringing with a Christian Scientist mom in Rhode Island, I could make a good one out of growing up among crazy Communists in New York.

Were there other people doing monologues at the time?

Not so much autobiographical stuff. There was Danny Hoch, hes awesome, but hes also an actor in movies and played different characters. The same with Eric Bogosian and Lily Tomlin. Anna Deavere Smith was figuratively and literally a towering artist, but she was doing a lot of reporting and also playing different characters. It seemed like Spalding was the only one who came out and just said, This happened to me 

How did you actually start?

I met Oliver Platt in Cambridge ÔÇö he was on a date with a woman I dated once ÔÇö and he invited me to audition for a local revue, where I did silly songs and attempted my first monologue for a few minutes.

Also around that time I went to see Spalding at Lincoln Center in Terrors of Pleasure and after the show I waited by the stage door and he came out to go mail a letter. He was between shows. I asked if I could walk with him to the mailbox. I said, ÔÇ£I want to do what you do,ÔÇØ and he smiled and was very encouraging.

What did he say?

I donÔÇÖt remember his exact words. I have a really bad memory, thatÔÇÖs why I make up so much shit. But IÔÇÖm gonna guess he said something like, ÔÇ£Well, do it.ÔÇØ ThatÔÇÖs what comedians always told me in comedy clubs, because itÔÇÖs all about getting stage time.

So you did it.

Nothing really happened until I moved to San Francisco. I found a space in a restaurant in North Beach and put up fliers on telephone poles. There was a jazz trio that opened and closed for me, and one night there was no one in the audience, literally no one, so I ran down the block to City Lights Bookstore and went to the basement and told everyone looking at books to come back with me and see a show for free. Eight people followed me. It turned out six of them were visiting from Germany and spoke no English, but it was people. It was people.

You didnÔÇÖt work from scripts, right?

I still dont. I cant write things down. I tried writing them down but it just didnt come out in the voice that I wanted. So I improvised. I told the opening band to come back in, like, 25 minutes, but eventually the improvs spread to two hours and the band  especially the drummer  would get drunk and not come back. At one of the last shows I said, I think the bands not coming back and I feel really close to you  Can I just tell you what happened at the end of my fathers life, when he had a stroke and died? They said, Sure, and I ended up just spilling all this stuff about his death. That was the performance where I realized that theater audiences are genius, and that I shouldnt be afraid of getting into subject matter that might seem a buzzkill in a comedy club. Because this is theater.

Those improvs became Josh KornbluthÔÇÖs Daily World, which was the show you saw and which ended up getting a rave review from the San Francisco Examiner and a good one from the Chronicle. It played venues around San Francisco for a year and then the next year I did Haiku Tunnel, which was bigger. I also got new fans from a one-person show festival called O Solo Mio. Spalding Gray was the headliner but they would force people if they wanted to see Spalding to buy tickets to other performers.

It was still a pretty minor movement, right?

At that time, yes, but we couldnÔÇÖt fend off capitalism. On one side you had the Spalding Gray impulse that was out of experimental theater, where the performers werenÔÇÖt there for superstar success and a sitcom. On the other side there were comedians who suddenly went, ÔÇ£Hey! I can go legit!ÔÇØ So there were suddenly a lot of solo shows by stand-up comedians, many of which were kind of ÔÇö as my dad would say ÔÇö potschked together from their routines. It felt at least to me like the form was being diluted, because it didnÔÇÖt come out of that original storytelling impulse.

So you were the only guy whose impulses were pure 

DonÔÇÖt put it that way! The truth is, I did it because it was literally the only thing I could think of doing at that point.

You got closer to Spalding, right?

After his wife Kathy Russo started being my booking agent, I got to hang out with him and it was incredibly gratifying. He really responded to the fact that I was doing this because it was the form for me, that it was how I could best express myself and wasnÔÇÖt a stepping-stone to something else. He would come through San Francisco working on his shows and weÔÇÖd talk about the process of finding and building the story. Even though I never worked with Spalding it felt like I was the apprentice in the very small guild of autobiographical monologuists.

ItÔÇÖs a much larger guild now. Is that a good thing?

ItÔÇÖs a good thing and a bad thing, not to sound too Jewish. When stand-up comedy was exploding in the ÔÇÖ80s, one comic said to me, ÔÇ£A few years ago when there werenÔÇÖt as many of us, there were, like, three people in the country who were fantastic at it. Now there are all these other people and there are also three people in the country who are fantastic at it.ÔÇØ

It would be a nightmare to have a world in which all theater was solo performance. ThereÔÇÖs a place in drama for having more than one character.

Well, that is the origin of the word drama. The Greeks brought in a second character to provide an alternate point-of-view.

That was the joke I was making.

Oh, okay.

Theater is basically the tension between two people having two different goals onstage.

So how do you convert a monologue, which is basically, the World According to Me, into something that shows different points of view?

With great difficulty.

I loved in Mike BirbigliaÔÇÖs movie Sleepwalk With Me, which was also adapted from a one-person show, when he looks into the camera and says, ÔÇ£Remember, youÔÇÖre on my side.ÔÇØ It really acknowledged the problem.

That was a great moment. ItÔÇÖs so incredibly true. By the way, I saw him present that movie in Berkeley. The theater wasnÔÇÖt set up for a Q&A so my wife Sarah and I sat in front and lit him with our cell phone flashlights. And that was the line I told him I loved, though I donÔÇÖt think he saw what I looked like because I was behind a light.

One of the big challenges of doing autobiographical monologues is that you have the deep need ÔÇö unless youÔÇÖre Eric Bogosian who can sometimes antagonize audiences on purpose ÔÇö to be loved. But how do you avoid the trap of whitewashing yourself, of airbrushing out the more dark and difficult things about you which are likely to be some of the most interesting things about you? A story needs an impediment to be compelling, but IÔÇÖm constitutionally unable to create evil people. So IÔÇÖm the impediment. IÔÇÖm the one who hasnÔÇÖt paid taxes for seven years and doesnÔÇÖt read the contracts I sign.

I could see how people watching Love & Taxes would be fed up with your character and his colossal irresponsibility. IÔÇÖm scared people will think youÔÇÖre some kind of symbol of white-guy entitlement when youÔÇÖve been really poor the whole time IÔÇÖve known you.

I was raised poor, I live poor, IÔÇÖm really bad at money. But I canÔÇÖt complain right now. We made this movie. It took eight years but we made it.

And you got Harry Shearer to be in it.

Those scenes with him and Patricia Scanlon as his partner were totally improvised. I couldnÔÇÖt believe that I was improvising with Harry Shearer. We did a take or two and I said to him, ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm realizing something. IÔÇÖm trying to be funny or clever and youÔÇÖre just listening and playing your character.ÔÇØ So itÔÇÖs never too late to learn from a master. IÔÇÖd bring my Josh character out and heÔÇÖd bring one of his Harry characters out and weÔÇÖd go at it, just living in that same space. Suddenly I realized IÔÇÖd been practicing handball against the wall my whole life and here was tennis ÔÇö or at least ping-pong.

And Robert Reich?

My sonÔÇÖs best friendÔÇÖs dad knew him and mentioned that heÔÇÖd just moved from Harvard to Berkeley. So I emailed his office and asked if heÔÇÖd like to play the part of Sheldon Cohen, whoÔÇÖs a real Washington tax attorney, and it turns out that Sheldon Cohen is a friend of his. Robert Reich was great. HeÔÇÖs a real ham. He didnÔÇÖt have time to rehearse or get a script ÔÇö he just came in a few hours before he had to be on CNN and improvised the scene. Then he emailed to say he had enjoyed doing it and especially liked working with my brother, Jacob. He wondered if Jacob would do some videos with him and that led to the documentary Inequality for All, which won a special jury prize at Sundance. TheyÔÇÖre making another documentary now.

That played at Sundance in 2013, right?

Yes. And Love & Taxes comes out four years later. Because of the movie, though, Jake has this successful collaboration with Reich. And when we started to work on Love & Taxes, he needed a place to say in San Francisco and ended up subletting a room in an apartment from the woman whoÔÇÖs now his wife.

All because you finally paid your taxes.

Yes, I owe it all to paying taxes. And the Violent Femmes for blowing my ears out. And Spalding.

Did you keep in touch with him until the end?

The strange thing  the awful thing  he and Kathy were coming to the first night of Love & Taxes at the Bank Street Theater in New York in January 2004. Before the show, I got a message from Kathy saying, Im so sorry, Spalding has disappeared, we cant make dinner. And that was the night  Yeah. It was more consequential than missing the opening of Love & Taxes.

You teach a monologue class now, right?

Yes, at Stanford, for the past three years. ItÔÇÖs a class thatÔÇÖs jointly presented by the Performing Arts department and the Ethics and Society program, so I call it the Ethics of Storytelling. We talk about how lying is cool. Then each of my students develops a little autobiographical performance. TheyÔÇÖre so awesome ÔÇö all of them. In my first class there was one young woman who had entered Stanford as a young man, an engineering major. Now she was a woman and a theater major. The monologue was really something.

The sad thing, though, is that none of my students had heard of Spalding Gray. And they need to. I still think of the form as how Spalding did it: extraordinary and beautiful and very primal, as if you were around the campfire, only without the sÔÇÖmores.