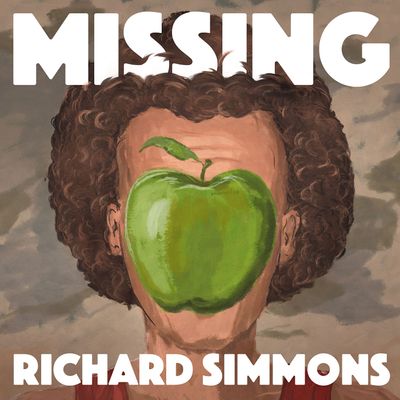

Let’s get this out of the way: Missing Richard Simmons is the best thing I’ve listened to in a long time and is, by far, the strongest narrative podcast out there right now.

There is a ton to love about this show. It’s lusciously produced, weaving together interviews, narration, and time and place with such verve that it makes each episode a joy to consume. It features a fascinating mystery centered around a compelling figure — Simmons, the fitness guru once synonymous with the ’80s who now exists as something of a cultural knickknack — that the show fleshes out as a near-saintly individual who, at the same time, remains eminently unknowable. And perhaps most intriguingly, it’s also refreshingly earnest; the show carries itself with an intense sweetness, an optimism so bright it shines with burning heat.

Despite everything that I adore about this show, and all that praise I just offered, it’s near impossible to look past the fundamental moral quandary that looms over its production and, really, existence: What right does a documentarian, or even a friend, have to waive a person’s right to himself?

Missing Richard Simmons follows documentarian (and former Daily Show producer) Dan Taberski as he tracks down and tries to understand what happened to Simmons, who, after decades of tireless friendship and generosity — through his exercise studio, personal classes, and overall persona — suddenly and inexplicably withdrew from the world. A big component of that process involves explaining Simmons, which Taberski does by way of situating the man both within the lives of the people that he’s brought into his world and within the culture at large.

It’s part private-eye tale and part biography, with the added twist of being structured as if it is some sort of narrative high-wire act: according to interviews with the producers, the “real ending” of the story is still up in the air, meaning it remains to be seen whether they actually get Simmons to talk to them, and whether the project ultimately ends up being consensual.

There are innumerable, valid reasons for a person to withdraw from the world, to stop accommodating the idea of who he or she is supposed to be. In its structure as a public performance of an ongoing investigation, Missing Richard Simmons triggers a gripping line of inquiry: At what point does a subject give up ownership over their story? When they become rich? When they become a celebrity? When they’ve built an entire public image on a vibrant generosity — when they give, give, and give, and as a result there are people who depend on them?

Or is the consideration in this case different altogether: Do they give up ownership, in a way, when others simply care about them, and they provide reason for concern?

These questions of giving up narrative ownership, and the right to being left alone, are present in so many other documentaries, and we don’t even have to look beyond the podcast format to find other notable examples where these very struggles play out — from Serial, arguably the OG of this high-wire gambit, to even the popular Hollywood history show You Must Remember This, which wields historiography as a weapon to relitigate, rediscover, and challenge the identities of celebrities who lost the nuances of story in the stream of history. In almost all of these analogues, the positioning of the narrators, functioning as journalists or historians, provides their shows with a structure of justification to carry out their respective investigations.

Missing Richard Simmons doesn’t have that sort of easy justifying framework. Taberski is a friend and former student of Simmons, and it’s evident that he cares deeply about the man. But it’s unclear if he’s operating as a documentarian or a concerned friend — and whether operating as both creates some sort of irreconcilable conflict vis-à-vis the moral imperative of each role. At one point in the first episode, we learn that Taberski had floated the possibility of making a documentary about Simmons even before the latter’s disappearance from the public, a fact that’s woven into the premise of the show.

“Why am I doing this?” Taberski narrates early in the first episode. “Because that year I got to know Richard, it made me even more fascinated than when I first proposed that documentary. I think he’s important. So much more so than his goofball public persona that he lets on. And also: because a lot of people who know him, and whose lives are changed by him, they’re worried. Or angry. Or full of grief. Some want to save him. Some want to just know that he’s okay.”

Where other documentaries justify themselves as journalism, Missing Richard Simmons seems to present itself as … portraiture, I suppose … and the portrait being painted is vivid and intoxicating. Simmons effectively comes through as an incredibly loving and lovable person, a man whose life seems to be defined by unending generosity. Taberski does a fine job retrieving the man’s complexity from a loud history that smooths off his edges. The story peppers what could easily be construed as hagiography with flashes of the dark: depression, possible suicidal tendency, an intense neediness, a likely fear of silence.

But is portraiture enough to justify the enterprise? It’s unclear. This leaves us with a state of affairs where the great work here takes place beneath a cloud of possible exploitation, which undermines some of the choices. Case in point: In its third episode, the show briefly veers into the question of Simmons’s sexuality, which doesn’t appear to have been discussed publicly very much, and the conversational tone of the narration obfuscates the importance of what’s being disclosed.

All these questions are exacerbated by a few meta-elements of the show. The podcast involves an audience participation component where listeners are encouraged to call in with their own stories about Simmons, which encourages a sense of participation that contributes to what essentially amounts to goading Simmons out of his privacy to provide answers. The show’s social-media campaign, which is aggressively joyful, seems to fly in the face of the very real darkness that pervades mystery — that this is a man who is hurting, and who maybe wants to be alone. All of these elements amount to a setup that’s reminiscent, weirdly enough, of the climax to the Dave Eggers novel The Circle, when (spoiler alert) a horde of drones, providing eyes to millions of ostensibly caring observers, chases after a character, unwittingly driving him to his death.

That’s a lot for the show to carry. At the same time, it wouldn’t be right to say this show shouldn’t exist, that this story shouldn’t be told. Simmons is a complex and powerful persona, a story of hope and care in a time of increasing unfeeling, and each episode has left me with a greater appreciation for just how much effort goes into the act of being open and generous.

The topics covered on the show are, to agree with Taberski’s assessment, important, which brings us to the true technical question that hangs over the show: How much of its value hinges on achieving its goal? Where does the story need to go to unambiguously justify itself?

It’s amazing to consider how much everything depends on whether they actually make contact with Simmons, and how that interaction plays out. There are so many outcomes that could render the project hollow: If the encounter ends up suboptimal, the whole thing could be written off as a shaggy-dog story. If it somehow turns out that Simmons was involved in the production all along, a fact dispensed of in a bizarre late-game reveal, we’d be left with emotional dishonesty and manipulation. If the show shies away from (or fails in) its gambit to connect with Simmons, turning inward such that it becomes a show about itself — the meta-discourse, the meta-critique, a show about shows, a story about the morality of telling stories — that would, alas, be a disappointment of the “it was always about me” variety.

Missing Richard Simmons is exactly halfway through the season, and has set itself up for a near-impossible task for the last three episodes: Can the team stick the landing without being irredeemably exploitative or emotionally dishonest? That’s the real mystery. For a show so exceptional, there’s an awful lot at stake in its second half.