Sometimes all a comedian can do is go onstage and tell the same joke they’ve told a million times before.

Before she became known for her legendary “I have cancer” set, Tig Notaro’s struggles — an infectious disease, a breakup, a mother’s unexpected death, and then a cancer diagnosis — didn’t appear in her material. The topics she discussed onstage at the time included a 15-minute-long joke about the many times she met ’80s pop singer Taylor Dayne.

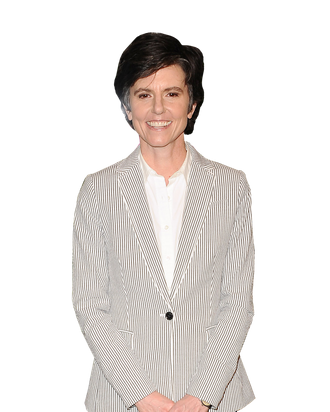

On the most recent episode of Vulture’s Good One: A Podcast About Jokes, Notaro talks about the long road to making that joke work, how it helped her find hope, and the time she forgot the all words to it onstage.

Listen to the episode and read an excerpt of our discussion below. Tune in to Good One every Monday on iTunes, or wherever you get your podcasts.

In terms of understanding how the Taylor Dayne story is built, I want to start by asking how true it is.

Well, it’s completely true — even more true than I reveal, because there were other times I ran into Taylor Dayne that I cut out, because it seemed so insane. I was originally trying to make it this series of run-ins with celebrities that are rude to me, and that I run into over and over. There was another celebrity, but it ultimately just felt like two different stories. I had to separate them.

I’ve had to become more aware of what is amusing. Not that I’m trying bits out on people, but that extra sense of, Oh, this is a story that people seem to like, so maybe I’ll try it onstage. I didn’t even know where to begin. I just knew when I told people about my run-ins with her, they were so amused. When I was originally sculpting the bit, it was around a half hour. It was so long. I had to whittle it down to 15 minutes.

There’s evenhandedness to the bit. It’s not a takedown of Taylor Dayne.

No, it’s not at all. When people come up to me after shows sometimes — I mean, I haven’t done that story in a long time — but every now and then, people would be like, “Man! What a bitch!” And I’d be like, “No. I’m not telling this story to shine like a negative light on this person.” It became a scientific experiment to me.

It was first recorded on your album, Good One, in 2011, but when was the first time you ran into her? When was that last time in the story?

The first time I ran into her was maybe in 1999?

When did you start doing it onstage?

Maybe 2009, 2010? I had never told anything that long. It was a challenge, and for a long time I couldn’t get the contraption off the ground.

How would you describe your material at that time? What was it that made you feel it was time to challenge yourself?

My material was a mix between one-liners, crowd work, and bits or stories that were probably no longer than three-and-a-half minutes. I could feel myself getting more and more interested in longer-form storytelling and jokes. Whereas a lot of those story-jokes were filled with a lot of jokes, for the Taylor Dayne story, I didn’t really have any plan other than, I’m curious if I can build some sort of structure here. Like I said, it really took a long time. It was one of my weaker bits I was determined to work out for six months.

What is your basic writing process for something like this?

I just jot down a word as a reminder when I go onstage. “Taylor Dayne” is what I go onstage with, just written down on a napkin. I rely on the fight-or-flight, sink or swim onstage, and that fear forces my brain to come up with something. It’s possible I would be better at stand-up if I actually sat down and wrote things out, but I think it’s the side of me that didn’t like school. I don’t want to sit down and work anything out that perfectly.

As you’ve mentioned, it started out as a half an hour, and has been sculpted down.

A very awkward and unfunny half-hour.

It’s interesting because a lot of stand-up starts with one thing and then people build out on it. What is the process of sculpting a thing down? You’re just telling it and hearing things that work?

You notice that nobody’s responding to this line, or this chunk never gets a response. Then you go back and think, Okay, even if they’re not laughing at it, is it a necessary part of setting up the story? If it is, you keep it, and if it’s not, then you just get rid of it. There are parts of stories that I can’t believe I used to keep in there, or jokes where I thought, What in my brain made me think I needed that line? You just have to cut the fat.

When it started working a little bit, what was the first glimmer that it might have legs?

When I first said, “And you’ll never believe who it was.” That was the big turning point for the story, because that line was in response to an audience being bored. I was essentially making fun of myself, like, I know, here we go again … but it’s true, she was there! Even now when I’m onstage and not telling the Taylor Dayne story, if there’s a hint of inflection or a word from that story, people get triggered. I’ll say, “And you are not going to believe …” and I’ll hear a rush of laughter. Oh, they think I’m calling that back.

How deliberate are you, not only in the words, but also in the rhythm of how you’re speaking?

I have no awareness of that until people ask me. It’s not a calculated decision where I think, Okay, I’m gonna slow down here. I’m gonna really take a beat on this word.

It’s a natural rhythm that you have.

For sure. There’s a weird dance with the audience. And it’s different rhythms on different stories or moments, and I have no idea. I can’t even imagine being that aware of how I pace out information.

I’ve heard that George Carlin would write everything out and put spaces in it.

That is the opposite of me. I always tell people, you’ll never find the lost writings of Tig Notaro — much less my pacing in little parentheses.

You once did the story for Conan’s After-Hours web series where you just couldn’t recall how it went. Do you remember what happened there?

I do. That Conan appearance was right in the middle of … I was days away from finding out I had cancer. I was newly out of the hospital, newly burying my mother, and that day my girlfriend and I broke up. I was still very ill. I went onstage to tell this story that I had told a million times and that was completely factual, and my brain just went away onstage because I had so much on my mind. It was really a leaving-my-body moment. Onstage I was thinking, These people think this is part of the bit, and I really didn’t know what I was going to do.

I lost the audience for a bit, but then, the more I made fun of myself for forgetting it, they came back. When I got offstage, the producer came up, I said, “I’m so sorry. I’m like really in a weird space and I forgot the story.” He was like, “No problem. We can just edit all of that out.” I was like, “You know what” — and it was partly because I felt, like, “Nothing matters,” in an inspiring, exciting way because I had lost everything, and also in this rock-bottom way of like, “You have come face-to-face with somebody that does not care” — and, I said, “Don’t edit it. Please leave it in.” Because I also knew for myself, it would excite me to see another comedian struggle like that.

Especially, for so long. It’s like two minutes.

No, I know. And, it was longer. They did edit some of that out. I remember just being like, Come on, brain. What happens next? And I couldn’t.

I’ve seen a lot of comedy, and I’ve never seen anything like that.

Yeah, I really was at a loss. I remember just sitting there in my green room after, thinking, “Please put that out there. Please. Put that out there. Because I want people to see me gasping for air.”

The joke’s main line — “Excuse me, I’m sorry to bother you …” — that was what you said in real life?

Yes. The first time I saw her, I felt bad interrupting her conversation. We were at an intimate party of maybe 30 people. Avril Lavigne was there as well. When my friend Pam was like, “That’s Taylor Dayne,” I wanted to give her a compliment but I didn’t want to be rude and I didn’t want to be long. I genuinely loved her and just wanted to say, “Hey, you’re great.” Just, “Excuse me, I’m sorry to bother you. I just wanted to say, I love your voice,” and then bolt. I was so new to Los Angeles at the time, so that sort of dismissive moment of, “Yeah, whatever,” was where I was confused.

If you threaten my life right now and ask me to do the Taylor Dayne story, I would not be able to.

Really?

I could tell you about my run-ins with her, but with it leading up to the robot bit, I was like, Whoa, I completely forgot.

Yeah, you had the robot ending and then, it goes back down to be like, “You guys think I made that up. I didn’t make it up.”

In the version of the story you’re talking about, do I talk about us going on tour together?

No.

Oh, okay. Because that’s another part I went into, her representative calling mine about it. Then I go into this thing of, “What are we going to do? Go on tour together? You know, the T&T, back to back?” I’ve run into her so many times, and there are so many different endings. She did my Professor Blastoff podcast and after that, and she said, “Here’s my number.” Then, she’d heard I had cancer and texted me, “If you need anything, or wanna talk, contact me.” I did this whole other ending where I imitate me lying in bed with cancer in the hospital, not able to sleep. Who am I gonna call? I reach out to Taylor Dayne, of all people — the person that will not talk to me every other time in my life.

This bit came at a time when you were doing a lot of four-minute things. What did you learn from working on it and then pulling it off?

I really struggled with, Gosh, this isn’t really my style, to do 15- or certainly not 30-minute stories. But when I was able to pull it off, and it kind of became a signature bit for me, it was that example of not telling yourself no. I started to realize that whether I was doing a one-liner or a celebrity story, or talking about having cancer, my voice is going to be in any of that. I’m only going to be hurting myself by saying, “No, you shouldn’t do that. That’s not your stage persona. That’s not your typical style.” That bit was a turning point for me to go, “I’m gonna do whatever I want, because I proved I could do something I had not done in a decade.”

When you took your shirt off for Boyish Girl Interrupted, and the Indigo Girls bit at Carnegie Hall — though they’re very different jokes, they’re similar in a way that says, I’m Tig Notaro. I’m gonna do whatever my comedy is, whatever I think works.

For sure. Taking my shirt off, bringing the Indigo Girls onstage to do a concert in the middle of my concert — it’s like, why would I not do whatever I wanted to do? If something amuses me, why not see if it will amuse somebody else? And every time I took one of those risks, it made me grow and made me better.

I’d love for you to walk me through the This American Life performance of the Taylor Dayne story, both at the moment and what happened afterward. How do you think of that day now? If I remember correctly, it was right before your cancer diagnosis, you just got out of the hospital, your mom just passed away. Then This American Life happened and it was a huge success.

I told Ira Glass I thought this story would be good on the show. After he saw it, he was like, “I love this story but I feel like it’s best live, because there’s so much to your facial expressions, and the act-out with Kyle [Dunnigan, a comedian who is involved in the Dayne joke].” From listening to comedy and storytelling records as a kid, I didn’t need to see what was happening. My brain would make up whatever was needed, and I knew people would make up in their own heads what they thought I was doing. And Ira said, “Well, we’ll see how it goes. And then, if I feel like it will translate, I will move it to the radio show.”

Yeah, I was really not in a good place. I was standing backstage thinking, “I need this to go so well. I need it to be off the charts.” Usually, when you need and want something that desperately, it just doesn’t go well, but that bit did go well. I got offstage and Ira came running up to me and he was like, “I think that’s the best segment I’ve ever produced in my career!” And, I was like, “Really? Oh my god.” It was just what I needed. And he said, “How dare you tell me how radio works, but you’re right. It’s gonna be great on the show.”

It was really kind of explosive. He called me two days after it aired and said, “We want something from you, right now.” I was like, “I just got diagnosed with cancer. I’m not in any place to be doing anything.” And he was like, “You should do a show about that!” I was like, “Oh my gosh, you’re insane.” You know? You have the Taylor Dayne bit. Let me go away and have cancer now, because I didn’t know I had it when I was onstage for the This American Life performance.

There were already articles and interviews I was doing because of the This American Life segment. I had book deals coming. People were thinking I was having a breakout moment and then, boom! Cancer diagnosis. I was like, Well, there goes that. Little did anyone know. It was a very pivotal moment.