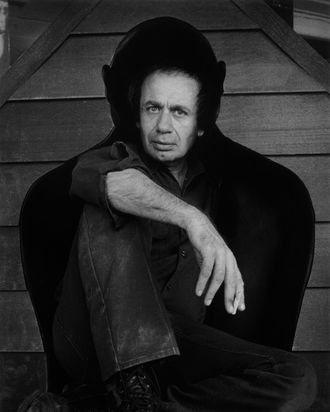

Vito Acconci, who died this morning, was the art worldÔÇÖs man in black, our mysterious you-want-it-darker Vito di Milo ÔÇö a troll body from another time with the mind of a poet who made art of the American night. Always dressed in black, always smoking, rocking ÔÇö almost davening ÔÇö as he spoke in florid sexual-architectural-dream metaphors, Acconci is conceptual and performance artÔÇÖs anti-hero, DylanÔÇÖs ÔÇ£creature void of form.ÔÇØ Acconci once conceded to Richard Prince, who asked him if his voice might have helped him lure women, that it ÔÇ£lulls you through a dark disturbed night promising intimacy, sincerity, integrity, maybe some deep, dark secret.ÔÇØ

In August of 2015, as I was preparing to write about art in public spaces and why AcconciÔÇÖs own fabulous, wild designs were never realized, in his shelf-filled, archive-like Brooklyn waterfront studio at 20 Jay Street, he read me his rejected divine proposal for a dream park for the Highline, a plan to include moving trees and fields, different vistas, a ÔÇ£twisting sky and magic carpet, a space city of the future.ÔÇØ And I cried in front of him, thinking of all the possible public futures lost to New York.

Even though he stopped performing more than three decades ago, Acconci is best known for his ultraradical early performative work. Particularly Seedbed: Between January 15 and 29, 1972, Acconci lay beneath a tilted wooden floor built in the Sonnabend Gallery at 420 West Broadway. That was it, except for a little speaker in one corner. Over the course of three weeks he masturbated eight hours a day while murmuring into a microphone, reporting his thoughts and fantasies of those walking above him. Things like ÔÇ£YouÔÇÖre pushing your cunt down on my mouthÔÇØ and ÔÇ£YouÔÇÖre ramming your cock into my ass.ÔÇØ He changed art with that piece just as surely as Duchamp once changed art with his Readymades, using his own body and id as his found objects.

All the elements of AcconciÔÇÖs art are in that performance: the architectural intervention, changing everyday space into something you have to negotiate and think about and treat as another real, even uncanny element. The artist is both present and not present, trying ÔÇö as all artists do ÔÇö to behave in public the way he does in private while keeping both states off balance, contested. His projected fantasies of footsteps above and recitation of his behavior and inner thoughts below make the artist both producer and receiver of the art, and the viewer is voyeur and participant. This sexual-conceptual, seductive, strange feedback loop brought into almost perfect balance artÔÇÖs simultaneous ultra-awareness and its trance state.

Sometimes Acconci was accused of sexism. And itÔÇÖs true, he did a lot of strange things with women. He had a woman cover him with lipstick kisses and another take his penis in her mouth while he tried to get away; he tried to block a naked woman from being seen by an audience and tried to pry open another womanÔÇÖs closed eyes. He always wanted to get inside other bodies and psyches. He also did a lot of equally intimate things to his own body. In 1971 he made Trappings, in which he carried on a conversation with his penis; Claim consisted of him sitting naked and blindfolded in a wrecked Soho basement swinging a lead pipe at any intruders while repeating threatening phrases. In Project for Pier 17 he stood in a ruined West Side pier at night, confessing to anyone who came to see him. In Following Piece, from 1969, he followed strangers until they went into private spaces. In other works he bites or rubs himself raw, tucks his penis between his legs or squeezes his breasts in an attempt to become a woman.

All these works vividly replicate and reflect states of deep love, loss, obsession, control, loneliness, and anger. Among many other inner and outer things, AcconciÔÇÖs ÔÇ£dark disturbed nightÔÇØ conjures a New York state of avant-garde mind and ethos that doesnÔÇÖt exist anymore and of which he was the tattered, incessant, solitary, melancholy Dionysian god.