Of the two possible ways to describe Resistance Radio: The Man in the High Castle Album, produced by Danger Mouse (a.k.a. Brian Burton) and musician Sam Cohen, one is simple, the other psychedelically complex. On the one hand, it’s an album of covers of 1960s classics by contemporary vocalists like Beck, Norah Jones, Angel Olsen, the Shins, Sharon Van Etten, and more. On the other hand, it’s an attempt to imagine what might play on a radio station run by those resisting the Nazi regime in Amazon’s TV series The Man in the High Castle, which takes place in an alternate history where America lost World War II. Oh, and though the the characters on the show mention that radio station in passing, and Amazon has set up a site where you can listen to it, the songs on this Man in the High Castle album haven’t actually appeared on The Man in the High Castle, the show. It’s hypothetical music for a hypothetical universe.

Despite the album’s dizzying conceptual heights, Burton and Cohen kept Resistance Radio grounded with a 1960s-appropriate approach to production. They reconfigure standards like “Nature Boy” and “The End of the World,” but still stick to styles available in the show’s 1962 setting — minus rock and roll, which, they imagined, might not spring up so easily under a fascist regime. Vulture caught up with the two collaborators to talk about imitating the ’60s, putting an album together in a matter of weeks, and whether a soundtrack to a resistance against fictional Nazis has anything to do with the resistance to Donald Trump.

This project started out with Amazon reaching out to you to do a cover of a song for the show?

Danger Mouse: Myself and Sam, we weren’t really that interested in necessarily doing something that was covers. Then when we decided to see what would happen if we tried it, because we had some time, we really liked the result we got, and thought, “Man, what if we just did a whole album like this? That would be worth actually doing.” We only had a few weeks to get it all done. The idea was they were gonna give a bunch of people three or four weeks to do a song, but I was like, “We could do a whole album in three or four weeks.” We went back to them with that idea after we saw that we could do it quickly. I had time off in December, but I don’t do good with time off, so we filled it up and made an album.

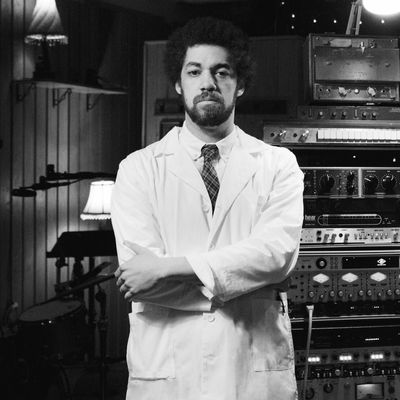

Sam Cohen: I came in because Brian asked me to. We’ve been working on a lot of stuff together and I am way into music from the ’60s and ’50s. I think he thought I would be a good guy to collaborate with on the project. So he reached out early on when he was still figuring out if it was gonna be that one cover thing or a whole project. Neither of us were really sure if we could make a record of covers cool. I called some of the people I play with regularly in my band and on albums that I produce, and just cut stuff live and pretty fast. Nothing precious. We did it at my studio in Brooklyn and we were like, “Oh, this definitely has a vibe.”

How did you decide which songs to pick?

SC: It was coming from all over the place. It started with [Amazon Studios head of music] Bob Bowen. He sent a really long list of songs that he had in mind for this. Some of it was songs that have been used on the show, the original versions or earlier versions. For a lot of these songs there’s so many versions of them out there. “Speaking of Happiness,” Brian brought that one in and said, “I’ve always loved this song. This would be a really cool opportunity to do it.” Stuff like that. “The End of the World” is one of my favorite songs, and that was on Bob’s list.

Were you trying to use production methods that would fit the world of the show?

DM: Oh, yeah. The way it was recorded and everything, the instruments that were used and the techniques and stuff like that — we tried to make sure it was period accurate. Stylistically it was like, “Well, we can’t get into this kind of style because these kinds of guitar pedals wouldn’t have been around back then and that certain kind of distortion wasn’t really being used.” We stayed away from certain things like that. Some of the stuff we felt we could’ve made it sound a little bit cooler for now, but we wanted to have that real, accurate limitation of what was going on.

SC: We were shooting for an old sound. I know that’s what Amazon wanted, too. It was a sort of a thing where it was like we were going to try to do it in, if not the original style of the tune, in a contemporary style. Say, it’s a doo-wop song or something. It didn’t have to be done in a doo-wop style, but it would have had to be done in a style that existed on or before 1962. So we might change it to a country song, but it would still have to sound like country from 1962 or before, etc. I think for our purposes we felt like maybe rock and roll probably wouldn’t have existed in the same way, in that context [of the show]. Our version of “Nature Boy” is a little bit rock and roll, but there’s not a lot of that on there. It’s mostly sadder, weirder, darker, vibe.

How did you decide which songs to pitch to which singers?

DM: We had to do all of it in one go, so we recorded the entire album, musically, before we were able to ask people, “Would you do this song?” We just had to hope, y’know that they would do it. We had somewhat of a basic key that we thought they could sing it in. We didn’t have time to really go back and forth and rerecord. We did all the backing tracks, the basics of the band — guitar, bass drum, piano — in four days, five days. Then we brought in strings and horns and backing vocals for a day apiece on each one of those. Then we would start sending the tracks out to people.

SC: Sometimes we had no idea. We were just like, “Let’s record this song. We’ll figure out who will be good for it.” Other times it was we had one person in mind who would really be great. “End of the World” was like that. I think we were thinking either Sharon or Angel. I knew Sharon a little bit, so we reached out to her first, because she was one of the very first people who signed on. Then hers came out so great [and] that lead to more people signing on. We had talked about Angel Olsen from the beginning, but none of us knew her, so that was one of the last people we reached out to. But at that point we had a bunch of finished versions to show her so that it wasn’t like reaching out to a stranger with just the idea of doing a covers record.

DM: A lot of these songs were difficult songs to attack, because they were very famous already. You don’t wanna really mess with some of the classics. But we also purposely picked songs that that people didn’t know, so that there could still be discovery on this album. It’s about half and half, some songs you know, some songs you don’t know. I would imagine that artist-wise there’s still a bunch of artists that people wouldn’t know either. People who know Norah [Jones] and Beck may not know Big Search or they may not know Curtis Harding or Benjamin Booker or something like that. It was important that they were gonna let us use some smaller artists and songs that weren’t necessarily famous.

Had you watched The Man in the High Castle before you started this project?

DM: I had heard of the show when they approached us, but I hadn’t seen it. So myself and Sam watched all of it in the first or week or two as we were recording the stuff or right before it. Then, the election happened, so it was an interesting time to record the album in December. There were definitely some things about the show were seemingly prophetic — some things, not all things, obviously, but some things.

When you debuted this project at South by Southwest, there were a bunch of Trump supporters who thought of it as being opposed to Trump? Within the fiction of the show, this is anti-Nazi music, but do you also think of it as being political in our environment?

SC: It’s been interesting to see how an element of protest has been connected to this project, because “Resistance Radio” and the word “resistance” has taken on a whole other connotation since recording this. I think I’d be pretty brazen to say that my initial thought when I decided to participate in a record of covers for Amazon was that it would be some politically radical thing to do. Incidentally, it sort of worked out that way. But what I can say is that the show definitely has an uncomfortable relationship with what’s going on politically today, and the atmosphere among the community of musicians who worked on it was pretty gloomy right after that election. I think our task was to sort of interpret these songs through the lens of a Nazi-occupied United States, and nothing about the current climate hurt our ability to do that.

DM: These songs are already written. It’s not like we’re writing songs about the time [right now] or anything like that, but in the choosing of the songs and the tone and the feel, we were already looking at, for the most part, of an alternate America where Nazi Germany is in charge, so that’s dark enough as it’s going to get, you know? I don’t think anything else could happen even in real life that would be darker than that.

It’s fascinating to think about the challenges of making these big standards, which, by now, we sort of take for granted.

DM: So many of the vocalists [on the album] could have been really big vocalists if that’s what it called for. You hear the Sharon Van Etten song, you hear the Beck song — not that they’re not doing well on their own — but both were pop songs of their day, and these guys really pulled them off. So even some of the somewhat indie-rock people on here sound great when the songs are written a certain way and presented a certain way, it’s definitely a different context.

This isn’t a soundtrack itself, but did it make you think about what it would be like to track a show or a movie in a more traditional way?

DM: I’ve often thought about that, yeah. I mean, I like things that are a little bit more song-based than score-based. I just went to a screening of Donnie Darko last night, and the soundtrack was so good in that movie. I like the score, too, but for myself, what interests me more is things that use a bunch of songs — The Graduate or Magnolia or Harold and Maude. That interests me more so than actually scoring. That’s more what these are. Maybe some of these songs will get used in their future episodes. I don’t know yet.

SC: I would love to do some of that and I’ve done a little bit of that. But it’s a completely different exercise. It’s creative in many ways and it takes you to different places musically, but you’re also very much serving the picture when you do that. Then in this, it was more like making a sound movie. Where you kind of get to be the director and cast the actors and be these characters and sort of paint the whole picture as opposed to just serving an element. So in that way it was really freeing. It was a side piece to the show as opposed to a score.

Did you want someone who hasn’t ever watched The Man in the High Castle to be able to approach this album without the context?

DM: Yeah, of course. We wanted to make an album that you would actually want to listen to now, not for any other purpose other than that you just like the songs and the recordings, and you just like the album. We spent some time on the track order, too. But once I heard “The End of the World,” I knew that was gonna be the beginning of the album. That just had to be the way it started.

This interview has been edited and condensed.