Each month, Boris Kachka offers nonfiction and fiction book recommendations. You should read as many of them as possible.

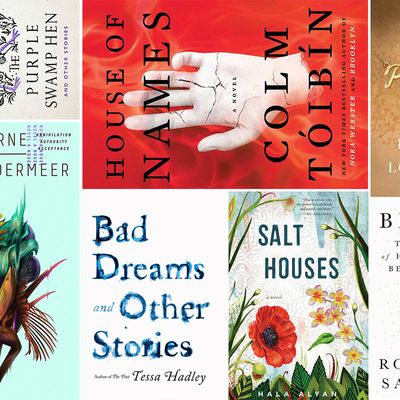

Priestdaddy, by Patricia Lockwood (Riverhead, May 2)

The unofficial poet laureate of the internet ever since she published ÔÇ£Rape JokeÔÇØ in the Awl, Lockwood proves at least as good a memoirist ÔÇö as clever, compact, evocative, and forthright. Covering a time in her life when she and her husband moved in with her Limbaugh-listening Catholic parents due to a desperate need for health care, and flashing back to her conservative-but-eccentric upbringing, the narrative touches all kinds of cultural fault lines. But the details and descriptions are personal and unique, because Lockwood doesnÔÇÖt know how to generalize ÔÇö or how to write an awkward sentence.

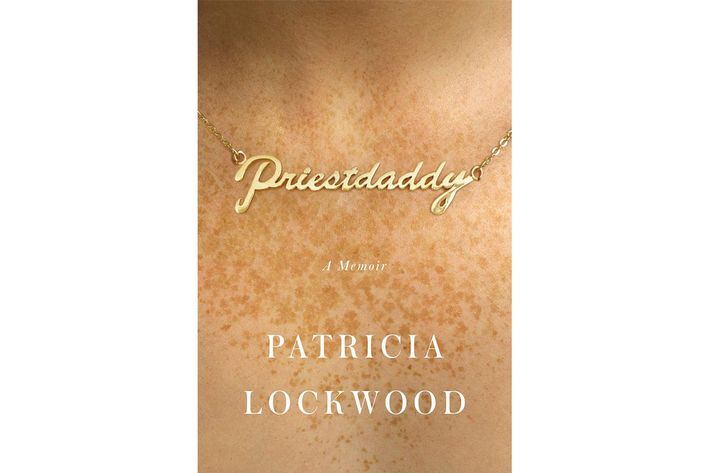

Borne, by Jeff VanderMeer (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, May 2)

No author of post-millennial dystopia can avoid scavenging and remixing genre tropes, but that tendency perfectly suits the world of VanderMeerÔÇÖs latest lush specimen, where everything is scavenged or remixed. Bioengineered monstrosities rampage through a ruined city, and humans scavenge in their wake. Our heroine, Rachel, discovers the titular creature, a strange cephalopod, in the fur of a giant man-eating bear and brings it back to her boyfriend, a former employee of a sinister and defunct biotech company. The cute creatureÔÇÖs mystifying evolution opens up a moral saga; just as absorbing is the misbegotten menagerie underfoot and overhead.

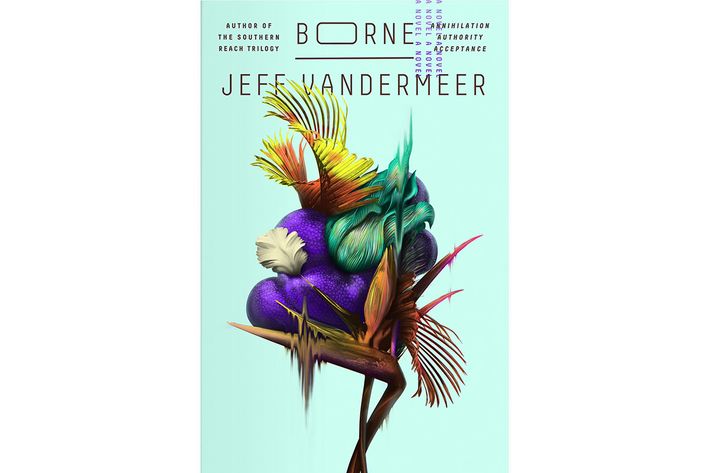

Salt Houses, by Hala Alyan (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, May 2)

Feeling homeless in their own land, Palestinians also have a diaspora, which AlyanÔÇÖs family panorama plumbs for a hopscotching, emotional study of the fractures that afflict even the luckiest of exiles. In the aftermath of the Six-Day War, some of the Yacoubs end up in Kuwait and Jordan and, in subsequent generations, Beirut and Paris and Boston. Families splinter, children rebel and return, and the matriarchÔÇÖs memories fade with age, fraying the broodÔÇÖs ties to Palestine. In the process, Alyan reveals the inner lives of people too often lumped together in the service of politics.

The Purple Swamp Hen and Other Stories, by Penelope Lively (Viking, May 9)

The British novelistÔÇÖs past life as a historian animates many of these 15 stories, most literally in the title piece, narrated by the lonely, exotic pet in a cold Pompeii household in the year 79, just before the eruption of Vesuvius. Other stories feature historians and biographers never quite getting the past right, or couples working out the discrepancies in their more personal histories. Despite the emergent theme, LivelyÔÇÖs collection is a smorgasbord of styles and tones, surprising in its surrealistic turns and also in its switchbacks to more pedestrian situations.

Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst, by Robert Sapolsky (Penguin Press, May 2)

If anyone can save evolutionary biology from TED talkers and pop-science fabulists, it might be Sapolsky, a Stanford neuroendocrinologist with a MacArthur grant, an obsession with stressed-out primates, and a dash of crunchy wit. Behave ranges at great length from moral philosophy to social science, genetics to SapolskyÔÇÖs home turf of neurons and hormones ÔÇö but all of it is aimed squarely at the question of why humans are so awful to each other, and whether the condition is terminal. If he risks overcomplicating, thatÔÇÖs refreshing in a field where evidence is often cherry-picked for cheap fun and tidy profit.

House of Names, by Colm Toíbín (Scribner, May 17)

T├│ib├¡nÔÇÖs reputation for exquisite writing and strangely muscular subtlety is long established, but only went mainstream with the adaptation of Brooklyn, one of his finest historical novels. Yet anyone who read his novella The Testament of Mary knows how powerful he can be when revising ancient stories and jolting to life the truly distant past. Here, he makes modern psychological drama out of the Greek mythological cycles of violence that destroyed Clytemnestra and her family, wresting human motives out of stories that might otherwise feel alien to our culture.

Bad Dreams and Other Stories, by Tessa Hadley (Harper, May 16)

Small events have massive consequences in many of the tales in this third collection from the English writer, who is finally getting her due as a miniaturist after the sharp heart of Alice Munro (even in her novels). Hadley often breaks the tethers of the short form by telescoping time, either in description or in reveries that reproduce the pungency of our most important memories ÔÇö and the insight that comes with their accumulation. Through her characters, she has a lot to say about youth and age, not as separate countries, but as states in constant communication.