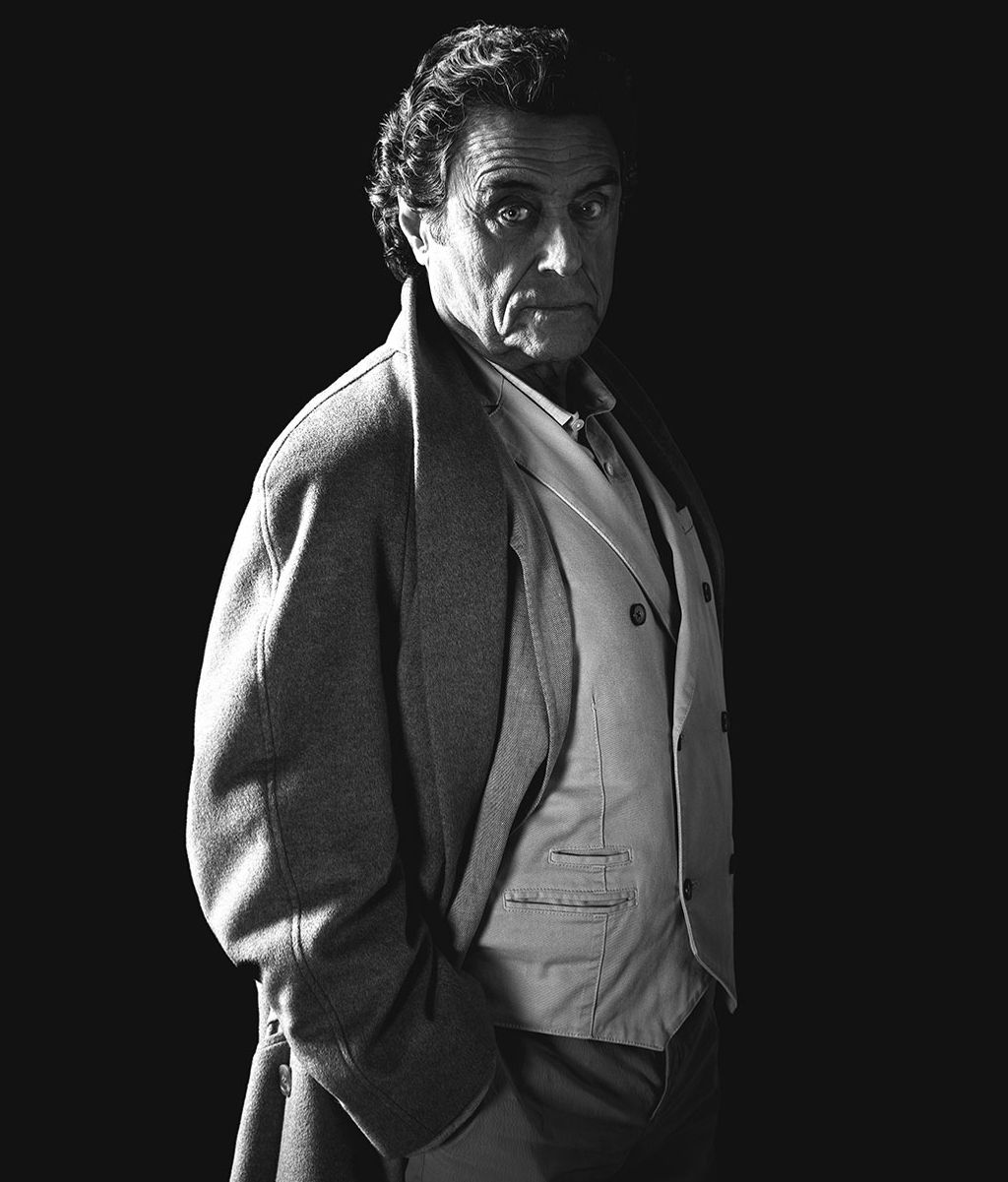

For someone with such a famous voice, Ian McShane is surprisingly nonverbal in his communication. That’s not to say he isn’t talkative — far from it. The 74-year-old English thespian can tell tales and shoot the shit for hours on end with nary a single dull moment. But his words are only part of the McShane experience: The rest comes from a dizzying array of gestures, facial expressions, body language, and difficult-to-transcribe mouth sounds. Getting a shot at a meal with him is like getting a ticket for a top-notch one-man show.

That said, McShane is at his best when he’s part of an ensemble project, and he’s as good as he’s ever been in his latest one, the Starz series American Gods. Created by Bryan Fuller and Michael Green and adapted from a hit Neil Gaiman novel, the story follows two con men as they traverse the country in search of Old World gods who have found themselves poor and out of favor in our current epoch. McShane is the older member of that pairing, a shady and winsome gent who goes by the moniker of Mr. Wednesday. You’re left to wonder whether or not he’s a god himself, but the character’s precise nature is somewhat beside the point: You’re gripped by him because he’s being played by Ian McShane.

That’s what we’ve come to expect from the man over the course of his six-decade career in film, television, and theater. Born in Lancashire and raised in Manchester, he made his debut as a rascal lothario in 1962’s The Wild and the Willing and has been barreling along ever since. In his birth country, he’s fondly remembered as the eponymous lead in a late-’80s to early-’90s show called Lovejoy, in which he played a mulleted antiques dealer who solves crimes while casually hanging out with his friends in the countryside. His next big act came in the aughts, when he played the fierce saloon owner Al Swearengen in HBO’s Deadwood. Wednesday is an enchanting mix of those two characters: soothing yet menacing, charming yet ruthless.

Over pasta at an upscale Italian restaurant in Soho — the personal choice of McShane, who knew various members of the staff — Vulture caught up with the delightfully vulgar, brutally honest actor about the frustrations of working on franchise pictures, his effort to get sober after developing a reputation as a party animal in the ’70s, and why he never, ever wants you to call him a national treasure.

Other than coming to this restaurant, what do you like to do when you’re in New York?

I always have to hit the MoMA. Usual thing. Walk through Central Park. The last several days, weather here’s been shit. I mean, I get it, my hometown’s Manchester, so I don’t bother about that. No, I just love coming here. I always have.

Do you remember the first time you came here?

Yeah. Fifty years ago. Did a play called The Promise. With me, Eileen Atkins, and Ian McKellen. Russian play, which was a huge hit in London. But we came to New York and we weren’t a huge hit. [Laughs.] You really got to know the town. And it was a great time. We were in the West Village.

Did you visit Times Square back then, when it was seedy? Was it a scary place to visit?

No, it was great! You think it’s creepy, you feel it, but who the hell knows, you’re 24 years old! You’re like, This is fucking great! We were at the Henry Miller Theater, which I think was turned into a pornographic theater. We used to go down to the Village and go to this club called the Electric Circus, which was half-price with no shoes. I mean, it was the Summer of Love! London, it was great, but I’ve always felt like New York’s got that little bit of a [squeezes face together slightly, makes percussive sound with tongue, like an electric crackle]. As much as I love London, New York’s always had that little [does face-and-sound thing again].

And you were a little wilder back then.

Yeah. [Laughs.] A little wilder. I put myself about a bit, as they say.

Now, we have to talk about perhaps the most important part of your career. A pinnacle, really. Your narration at the beginning of Grace Jones’s 1985 album, Slave to the Rhythm. Y’know, the one where you say, “Rhythm is both the song’s manacle and its demonic charge” and all that. How on earth did you end up doing that?

[Laughs.] I knew Trevor [Horn], who produced it! We were sitting — where the hell were we sitting? Right, there used to be a great fish-and-chips shop in London behind the Notting Hill Gate Cinema. Served great fish and chips. I mean, really. And I was in there and Trevor, he was there at another table, and he said, “What are you doing after fish and chips?”

He said, “Orson Welles is dead, and I need a voice” — it was very funny — “Orson Welles has died, and your voice is pretty good. Why don’t we come back to the studio, we’ll smoke a large spliff” — which we did. We went back to his studio, which was around the corner. And he said, “I want you to do this Slave to the Rhythm.” So we did, had a great time for two hours, went home and that was it.

So, on to American Gods. I think it’s great.

It is, isn’t it? It’s all right, talking about a show that you can look at and it’s actually interesting to talk about.

How much of it have you seen?

I don’t look at rushes. I’m not producing it or directing, so there’s no point. I knew we were in capable hands. And when we went down to South by Southwest, they showed the first episode on a big screen. And I was actually fucking blown away. Which is kind of nice. A lot of shows talk about pushing the envelope or whatever, being a bit different. But this is. I’ve worked with Michael Green before.

Right, on Kings, the show where you played the king of an alternate-universe America.

Which was your classic case of a network saying, “We want a cable show.” And you do it and say, “Well, there you are.” And then they don’t know what the fuck to do it. They’re just not built to do that, ’cause they want 22 shows a year: the same show every week, with a twist at the end. And [Kings] was far too revolutionary. We got to do 13 episodes, which I was still amazed by. Probably because they had fuck-all else to do. When [American Gods] came along, I didn’t know the book.

I heard you were initially approached for the role of Czernobog, the smoke god. The one Peter Stormare plays. He and Mr. Wednesday have scenes together, but they’re very different characters. How did that go down?

Well, it was all a bit strange. I got this call saying, ”Would you look at this thing called Czernobog?” And I read it, the script. And I said, “It’s very nice, but I can think of ten fucking actors who would be fucking much better than I would be playing this part. But what about Mr. Wednesday?” I didn’t even know the book then. And he said, “Oh.” I said, “Have a great show, whatever it be.” And we had a nice conversation. And literally, three days later, they came and said, “You know, we’d like to offer you Wednesday.” So I read the book and I was like, Fuck yeah.

Have you hung out much with your fellow Englishman Neil Gaiman?

On the plane last week, we finally got a long conversation. He’s interesting. Jewish Scientologist. Where does that come from? [Editor’s note: Gaiman is no longer a Scientologist.] But, I like Neil because he’s easy to talk to. He likes talking. [Deadwood creator David] Milch, same thing; Milch loves to fucking talk.

I interviewed Gaiman a few weeks ago and was struck by how he’s simultaneously charming and also clearly very aware of how successful he is. You feel like he’s thinking, “Yeah, that’s right, I’m Neil Gaiman,” but he’s still incredibly nice.

When we went to Comic-Con, Neil was there, and I knew he was big, but you don’t know the extent. I love being at fucking Comic-Con. But being with him there? Fucking great. They can’t wait for the show and he loves to talk about it in a very good way. And Bryan Fuller’s the same. Have you interviewed him?

Only briefly, at the American Gods press day.

Bryan’s out there. Very flamboyant, outwardly gay; doesn’t give a fuck. I think Bryan knew he was gay when he was like four.

And he and Michael have crafted this character that you seem uniquely well-suited to. One of the things you’re best known for is your vocal talent. How did you find the voice that you use with Wednesday?

It’s when you rehearse on your own beforehand. Wednesday has to overwhelm in the nicest possible way. Al [Swearengen] was more declamatory. Wednesday doesn’t give a fuck. Al gave a fuck, but Wednesday’s eternally optimistic. Al would say, [deep, intimidating voice] “Don’t fuck with me.” Wednesday would say, [faux-innocent, singsongy voice] “Why are you fucking with me?” Flowing. He doesn’t wait for a reaction. Wednesday says things and then he’s on to the next. So that’s part of why I charm Shadow.

Speaking of acting, you once said that, unlike Sir Ian McKellen —

Serena, you mean? [Laughs.] He’s one of my oldest friends, you know.

You once said that, unlike McKellen, who said he was born with theater in him, you had no such inborn desire for theater. What did you want to be when you were little?

My dad was a football player — soccer — for Manchester United. So I was brought up with that. I loved the game. I still do. And I played pretty well, but I wasn’t on that level. And you know as a kid the level you’re at. You gotta have the fucking talent. And I didn’t.

Was there cachet in being Harry McShane’s son?

That’s another thing: When I go home, I’m not Lovejoy, I’m not this or that — I’m Harry’s lad.

So when did you know acting might be something you’d want to do, if you weren’t born with it?

We had this new teacher in school when I went to grammar school, who taught geography. They didn’t have drama teachers then. He was the geography teacher and he said, “I’m putting on a play.” The first year, I was playing some small part. And he said, “Next year, we’re gonna do Nekrassov.”

Jesus!

Sartre’s political play. It was the first amateur production! And he said, “You’re gonna play Nekrassov.” I mean, you’re 15 years old. When I walked on, I sort of knew what I was doing. Very comfortable. And then we did that and he said, “Next year, we’re gonna do Cyrano and you’re gonna play Cyrano.” I said, “That’s great, sir. Can I go and play football now?” But I did Cyrano and it became a sort of a mini-event. People always talked about taking it on a school tour. At the same time, the National Youth Theatre was casting their net wider than London. [The teacher] said, “The Youth Theatre is coming. I think you should go and audition.” And so I said, “Okay, fine. Whatever.” And so Michael Croft, who ran the Youth Theatre, was from Manchester, so that was perfect. He found me and went, “You want to come down this summer?” That was fantastic. Then I auditioned for RADA. Two years at RADA, and spring term, [my roommate] said, “This agent, they can’t find a lead for this movie. It’s a 19-year-old, strappy, angry young man from a Northern town. I think you’d be perfect for it.” So I left a term early and went. I took a Green Line bus. It was a movie called The Wild and the Willing. And the rest is … [smiles, trails off.]

I was intrigued by something you said in an interview a while back which was, while you were at RADA, you did a lot of comedic training.

We had a great teacher there, Peter. Taught classical technique. But he’d go, “Next week, you’re going to improvise.” I’m like, “What’s that?” Or he’d say, “Next week, you’re going to do stand-up comedy.”

Good lord, Ian McShane doing stand-up comedy.

It’s a real test! I have fairly good jokes, but I can’t get up onstage and tell three jokes. At the time, the famous Bob Newhart had this album out which had a bit about trying to sell baseball to the Olympics. It’s great, it’s funny, it’s comedy. And I thought, I should do that with cricket! [Pauses.] I died a fucking death. I was going, “Now, this is cricket,” and there’s stunned silence. Peter said, “Too smart for your own good.” I said, “You’re absolutely right.” Drama school, mainly, for me, it was about girls and how to drink. But all those lessons are deeply ingrained. We had to dance. We put on tights and did ballet. Then we did fencing. It was a pretty all-around fucking course.

You played Richard Burton’s gay lover in Villain back in 1971. Were you worried about playing an openly gay character? It was much less common for actors to do that back then.

Not at all. No, Richard’s a great guy. They were the most famous couple in the world back then, him and Elizabeth Taylor. Just before we did the scene where he beats the shit out of me and then obviously we’re gonna have it on, he said, [imitates Richard Burton] “You know, I’m very glad you’re playing this part, Ian.” I said, “Really?” He said, “Yeah, you remind me of Elizabeth.” [Laughs loudly.]

At that point in your career, you were partying pretty hard. How difficult was it to balance work and play?

Oh, very easy. I was what you call a high-functioning alcoholic. It’s what we all were. No, really! You’d go to bed at three in the morning, pissed or whatever; you’d get up at six, have a shower, and get up and go to work and reel off the lines. But after a while, it takes a toll. [Laughs.] You get old. In the late ’70s and the early ’80s, I got married to my present wife, Gwen, who’s fantastic, and you sort of start to grow up and you start to think, I can’t be doing this shit. I’d never lied to my wife before and suddenly you find yourself lying about where you’ve been. Fuck it. So you go to AA and things change. It’s like you’re who you’re supposed to be. But it was fun. Fuck me, was some of it fun.

I mean, entertainment was a different world back then. You weren’t the only one partying in the ’70s.

Oh, completely. Now they’re paranoid. I mean, on a French film set, they have wine at lunch time, but in America? [Gasps in mock disgust.] When they see someone has a drink … It became this thing in the ’90s. Now they follow you around on film sets. Well, they always think actors are children, anyway. They have all these PAs follow you around. You’re like, “Would you like to come see me take a shit? What, do you think I’m gonna run away?” Yeah it’s a different vibe now, and it was fun back then. But there’s some great shit out there now, TV-wise. I mean, there’s some extraordinary stuff going on out there.

Shows like your personal favorite, HBO’s Tits and Dragons. Er, I mean, Game of Thrones.

[Laughs.] They made such a big deal out of [me saying] that. [Game of Thrones showrunners] David Benioff and D.B. Weiss were there at our opening the other night. We were laughing about it. It probably added 3 million onto their viewing. When the internet rises up in arms, saying, “You’ve spoiled it!” I thought, “What have I given away? I’m in one episode of Game of Thrones — what do you think, I fucking walk away unscathed? I don’t think so.” I think somebody had actually invented that phrase. I’d heard it somewhere. They said “dragons and tits,” and I remembered that, and I said, no, “dragons and tits,” it doesn’t flow off the tongue as easy as “tits and dragons.” Put tits first, not dragons.

Do you think it weakened your character’s message to have him die so quickly? He’s preaching pacifism, but then he gets killed and the lead goes on a violent rampage to avenge him.

No, he had to get killed. I mean, that’s it. Why would they let him live? That’s the whole point. Jesus didn’t live, did he?

Do you watch Game of Thrones at all?

I want to watch it when I can really properly watch it. I’m saving it to binge watch. I saw some leading up to it. My grandkids love it.

Along those lines, you’ve done a fair amount of work in big, dumb movies like Hercules and one of the Pirates of the Caribbean movies. What’s different about the acting process when you’re doing something like that?

Oh god. God. It’s a just a … You can’t … You have to be patient, but they go on forever, you know, just go on forever. Johnny [Depp]’s a great guy, I love Johnny, he’s a great guy but at one point when you’re shooting those, you go [rolls eyes]. I remember I was doing a movie with Ava Gardner, at Pinewood, back in 1969, called Tam-Lin, directed by Roddy McDowall, and at the same time, Billy Wilder was shooting his Sherlock Holmes movie there. He’d been there about 20 weeks. I was at the bar and there, outside, was Wilder, with a martini. I go, “Mr. Wilder, I just want to say, I’m a huge fan of your movies, and how’s it going?” And he said, “Thank you. How’s it going? After 20 weeks, it’s like fucking after you cum.” On those movies, that’s what it’s like. When you’re doing Hercules, it’s, like, Well, I’ve just cum, but I’ve gotta keep going. Because that’s what they’re like! They’re relentless, they’re machines, because they shoot so much material. I did a so-called artistic one called Snow White … [Struggles to remember the rest of the title.]

… and the Huntsman.

And the Huntsman. We were the best things in it, the dwarves, but by the time we had 6,000 prosthetics and our false asses put on, they could only shoot with us for three hours. So it was a bit sad, that. And the other one was … What was the other one I did?

Jack the Giant Slayer. You played a king.

Right. When you’ve got gold armor with a 50-foot train and a fancy beard, that’s the part. You don’t need to do any acting. It’s like, “Can I just cut all my lines and stand here? And sit on the horse?” [Director] Bryan Singer used to say, “Can you give the lines to the guy behind you?” and I said, “I can’t fucking turn my neck! I’m in gold armor, and every time I turn my gold armor, it squeaks! What the fuck is that?” Half the time, you’re giggling in those shows; and half the time, you’re thinking of the very large paycheck at the end of the day. What does it do? Diminish you? No, I don’t think so. But you have to be prepared because it’s a completely different way of filming. Acting is fucking boring to talk about. It really is.

No, it’s not!

No, it is! When a fan’s going, “How did you do that?” it’s like, “How the fuck do I know?” It’s what I do for a living. It’s a blessed thing to do. They pay you a fucking lot of money to get up and behave like a kid. Take all your fucking craziness out in what you do. When I get on the set, fucking anything goes. Know your lines, walk on the set, look at the other actors’ eyes, and then you fucking go for it. Milton Berle once said a great thing about so-called stardom. He said, “Better to be shit in a hit then a hit in shit.” When you’re part of something, even the smallest part … like in Deadwood, everyone that had a part in it was as important as everybody. The whole show was what mattered. It’s like with [American Gods]. It’s the show. I happen to be part of it and I’m going to be playing a lead in it. Which is great. I’m very grateful, whatever. But the whole thing around it is what makes it. It’s like they go, “Wow. What the fuck is this show?” It’s not just about poor Mr. Wednesday.

Obviously we have to talk about Al Swearengen and Deadwood. What spoke to you most about this character?

It was all there in the first one. I think David is just a … It’s always good to have someone in the room who’s smarter than anybody else. So in [American Gods’] case, it’s Bryan Fuller and Michael Green. But Milch has that in spades. Milch would watch what you did. He was there for every fucking scene and then he’d adjust. After the pilot, he then adjusted constantly, so it was never a full script. We’d get pages. We were fortunate in the fact that everybody was there on set. The editors were there, the writers were there, costumes were there, sets were there. They only went on vacation for two days in the entire fucking series. So you had this experience that David could work on a scene and then he’d go, “Well, wait, I need to go back,” and then he’d adjust.

The perfect example: One day, he says to me, “I’ve got this scene written. You’ve got a package, but the package is just a ploy. It’s just a McGuffin.” So then we do the scene, but the next day, he comes back and I walk down back into the saloon the with the package and go [mimes preparing to toss the package]. David goes, “You can’t throw the package.” I said, “What do you mean?” He says, “It’s got a head in it.” Who knew? It was like, Aw, fuck yeah. And then he keeps that, with the head in. I mean, that’s David. It’s just amazing. Every actor was there for the gig. It was amazing. Everybody brought their A-game in the best sense of the word. I was thrilled and excited to be there. It was like, every day, Wow.

What was the first scene you vividly remember shooting for the show?

It’s when I bring ’em upstairs with Trixie, in the pilot. She shoots the husband. Shoots one of the guys, one of the johns, and David looks up and says, “I think you’ve got to grab her by the cunt.”

Good lord!

Paula [Malcomson, who played Trixie] went, “Absolutely. Absolutely right.” I was thinking, It’s not exactly the first thing you say to an actress: “Do you mind if I grab you by the cunt?” It’s not exactly the first thing. But it took all the barriers away from whatever. And it’s amazing! It’s true! It was.

Was it heartbreaking when Deadwood got canceled?

No, it was weird. I remember having this kind of Zen attitude. I started calling everybody and saying, “We’ve had three years of amazing work. It’s been fantastic. Everybody has been wonderful.” Then, after sort of calming myself down for two months, it was like going out and being like, [ragefully] Jesus! Like going crazy, thinking, What the fuck did they do? Whatever happened to Deadwood was something that happened with the production and David Milch — I mean, David’s not an easy character. Thank God! He can’t be. But who knows what happened. Hubris, ego, money? It was an expensive job.

I would be remiss if we didn’t touch briefly on your years playing the title character in Lovejoy. Even though it came out way back in the ’80s and ’90s, it’s still probably what you’re best known for in the U.K. I hadn’t watched it until I was preparing for this interview, and it’s delightful. So soothing.

It’s Sunday-night TV.

What does that mean? Is that a British thing?

Sunday-night TV means the whole family sits around and watches TV. This was before cable. People watched; couldn’t stream it. They didn’t have three televisions. Televisions were still expensive. Families still got together and watched television on a Sunday night! Of course, a lot of people would go, “Ah, you fucking sold out.” But Lovejoy was great.

During the Lovejoy period, you also came out with an album of songs, improbably enough. How did that happen?

We were in London and they came in and said, “Would you like to make an album?” And I said, “Yeah, well, obviously, the kind of album I would want to make isn’t the kind you want to make.” But I mean, you’ve obviously gotta go along when you make an album like that. You’ve gotta think of the character, because they’re thinking commercials. You’re going with Lovejoy as a basis for it, so you sing lot of oldies and a few new ones, whatever. So you go along with it.

But I had a good time with it, and I did dedicate it to my wife, and I have a gold record. It sold 100,000 copies. But then, of course, they review it like it’s a serious record, you know? Like, Are you out of your fucking mind? You’re taking me seriously? It’s for a purpose, it’s fun, it’s nice, it’ll get played one or two times. Twenty-five years later, somebody will show a video of me with hair down to here, going, [sings] “The party’s over, da-da-da,” and you’ll go, I remember that! And you’re gonna laugh.

You still have very voluminous hair.

You do, too!

Thank you, I appreciate it. You’ve managed to maintain it. Do you have a hair-care regimen?

Get out of the fucking shower, put some grease on it.

What was it like to be a sex icon for middle-aged women while you were doing Lovejoy?

Well, they make you that: the housewives’ favorite. In England, you become three things. You become a hit. You become a sex object for the over-40s. And then they finally say, “Oh, you national treasure.” [Rolls eyes.] Oh Jesus, that awful word. You think, Did I fucking die without knowing it? The last thing I want to be. A national irritant, perhaps. But a national treasure? No fucking way.

This interview has been edited and condensed.