For all the moaning about Brooklyn novelists over the past two decades, thereÔÇÖve been very few novels set in Williamsburg. As if following a Paul Auster homing beacon or reading Paula FoxÔÇÖs Desperate Characters as an instruction manual, most Brooklyn novelists have settled in South Brooklyn and set their books somewhere in the orbit of Prospect Park. The narrator of Ben LernerÔÇÖs 10:04 works at the Park Slope Food Coop and walks to Brooklyn Bridge Park after his shift and sheds a tear (ÔÇ£a mild lacrimal eventÔÇØ) looking across at Manhattan. Colson Whitehead wrote the quintessential set piece treating a late-night trip to a Fort Greene bodega in John Henry Days. We know from Jonathan LethemÔÇÖs Motherless Brooklyn that most of the barflies at the Brooklyn Inn circa 1999 were somebodyÔÇÖs assistant. To tell by Adelle WaldmanÔÇÖs The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P., many residents of Clinton Hill live their lives as if it were the 19th century with better appliances. Though there have been fads for narrators with neurological disorders or doubled selves and minor outbreaks of magic realism in recent years, realism, refinement, old brownstones, and hardwood floors are the hallmarks of these books. They play by the rules and, at their worst, read as if they were written to pay the rent.

That canÔÇÖt be said of the novels of Tao Lin: His Taipei is as good a novel of post-gentrification, post-Xanax, molly-addled Williamsburg as we have. (The recent standout pre-gentrification novel is Jacqueline WoodsonÔÇÖs Another Brooklyn.) But LinÔÇÖs novels arenÔÇÖt wide-angle affairs. His narrators occasionally give voice to acid expressions of fellow feeling (ÔÇ£we are the fucked generation,ÔÇØ a character in Shoplifting From American Apparel writes into a chat box), and theyÔÇÖre defined by their alienation. They arenÔÇÖt creatures of a milieu. TheyÔÇÖre locked inside themselves.

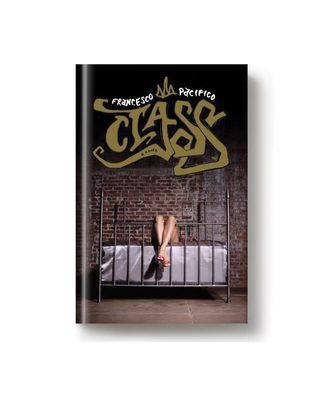

So maybe it makes sense that the novel to take on the Williamsburg of high-rises and clapboard houses, just-finished condominiums, and Bedford Avenue boutiques ÔÇö the hipster dreamland ÔÇö should be written by a foreigner. Francesco PacificoÔÇÖs Class does a lot of things you donÔÇÖt see American novels do much of these days. ItÔÇÖs a sex farce: The fucking is de rigueur, thereÔÇÖs a lot of it, and itÔÇÖs treated the same way as breakfast, which often is the thing that comes next. ThereÔÇÖs a lot of explicit discussion of money, with fees for magazine pieces, prices of plane tickets, bank deposits received from parents, and windfalls of inherited wealth quantified in euros. Lifestyle details are catalogued as if they were points of pride: I donÔÇÖt know of an American novelist whoÔÇÖd bother saying that their characters go to Film Forum too much. There are scenes at an n+1 party and at a party at Gary ShteyngartÔÇÖs house ÔÇö thatÔÇÖs usually not done. Mixed in with those details are a few that ring false. I lived in Williamsburg for a couple of years, and IÔÇÖve never heard any Americans or any foreign transplants refer to the neighborhood as ÔÇ£Willy.ÔÇØ The Burg, yes. Billyburg, yes. But Willy?

ThatÔÇÖs what Ludovica calls it. SheÔÇÖs one of the set of rich Italians whoÔÇÖve come to New York to follow their dreams, or as Daria, the narrator of most of the novel, would put it, seek ÔÇ£personal fulfillment.ÔÇØ Daria wouldnÔÇÖt call them rich or middle class, either; her preferred term is ÔÇ£bourgeoisie.ÔÇØ She works as a travel agent in Rome, writes reviews for a communist newspaper at night, and vacations in New York to take molly and take lovers. Ludovica has a lousy job moderating viral-marketing chat rooms in Italian for campaigns that donÔÇÖt seem to have much viral potential. SheÔÇÖs come to Brooklyn with her husband, Lorenzo, an aspiring filmmaker on a philosophy fellowship at Columbia. HeÔÇÖs made one short film, a catalogue of clich├®s starring Ludovica as La Sposina, ÔÇ£the pretty little bride.ÔÇØ Everybody knows itÔÇÖs no good, that LorenzoÔÇÖs 34 and unlikely ever to make a movie, but somebodyÔÇÖs told him Wes Anderson might hire him as his assistant director (ha-ha ÔÇö not a joke an American would commit to ÔÇö itÔÇÖs too pathetic and too real), and he hasnÔÇÖt given up hope: HeÔÇÖs one of those. Ludovica has given up. When the novel begins, sheÔÇÖs already ready to go back to Rome. ThereÔÇÖs nothing more Brooklyn, after all, than thinking about leaving it.

Pacifico ÔÇö who wrote the book in Italian in 2014, then translated it himself (with Mark Krotov) into English ÔÇö breaks a lot of dearly held rules of point of view and narration in a way that would be called experimental if an American did it. You could also call it sloppy, which it is by design. His style is a form of gossip. Daria narrates from inside the heads of Ludovica and several male characters, most of whom sheÔÇÖs slept with, two of whom she met as a teenager at summer camp. She knows and tells of things she couldnÔÇÖt have heard or seen, often spiked by parenthetical asides from her own life and firsthand knowledge of the characters. Toward the end of the book, the narration roves in a way that strikes me as a form of showing off. The plot of the book, about LudovicaÔÇÖs and LorenzoÔÇÖs infidelities, recedes, and the ending that comes before the coda veers into surrealism, putting a couple of characters in hospital beds. ItÔÇÖs unsatisfying in two ways most of the novel is very satisfying. It isnÔÇÖt funny, and it suggests the sort of redemption that the rest of the book rejects explicitly.

The only significant American character in Class is a novelist named James Murphy, whoÔÇÖs said to have ridden the David Foster WallaceÔÇôJonathan Franzen wave to the best-seller lists. That heÔÇÖs named after the leader of LCD Soundsystem is probably a nod to Tao LinÔÇÖs Richard Yates, with its doomed couple Haley Joel Osment and Dakota Fanning, and a joke about the aging hipster whoÔÇÖs losing his edge. Aside from being somebody for Daria to have a fling with and a celebrity pal for her friend Nico to write home about, Murphy is present for Pacifico to embed a sharp critique of the American novel. Daria says of their affair:

He canÔÇÖt understand whatÔÇÖs happening to us. James is the champion of literary empathy; these modern Americans are so good at making the reader feel human ÔÇö they think literature connects us all. They became important under George W. Bush, these writers, emerging as an antidote to his regime, so now they feel obligated to provide a model of absolute virtue at all times to suppress every individual interest, to avoid every class vice. Thus they convince themselves and their readers they have no class vices at all, even as they get big grants from billionaires who indulge them with one hand and take from the poor with the other.

Take that, recipients of the MacArthur ÔÇ£geniusÔÇØ grant! Or as Nico tells James: ÔÇ£You never let your characters just fuck. You never have them enjoy it and just leave it at that. ThereÔÇÖs a conflict or anxiety or regret every fucking time! ItÔÇÖs like you donÔÇÖt know that thereÔÇÖs actual pleasure in the world. ItÔÇÖs really puritanical.ÔÇØ

*This article appears in the June 12, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.