Day is turning to night, fair weather to one of those early-spring squalls that make the savanna west of Melbourne, Australia, feel like Ireland with eucalyptus trees. We are in the last day of location shooting on the series finale of The Leftovers, sheltering in a 19th-century clapboard church while star Carrie Coon shivers outside in aging makeup and a $10,000 wig, genuine frustration fueling the anger she needs to play a lovelorn recluse calling a nun a ÔÇ£fucking liar.ÔÇØ Seated in front of a monitor, wearing a cap with the logo of a kangaroo and the words ÔÇ£Leftovers Final Season,ÔÇØ is Damon Lindelof, the nervous showrunner, whose job is to create, then second-guess, and finally cut and polish his profound and bizarre follow-up to Lost.

Lindelof doesnÔÇÖt love being on set, even ÔÇö or especially ÔÇö when heÔÇÖs there to say good-bye to his own critically beloved gospel of grief and faith. Conclusions are a difficult subject for him. Running Lost in his early 30s, the rookie creator spent six years shepherding the hit ABC show about time warps and smoke monsters through an era when fans, connected and emboldened by internet message boards, began demanding answers that older auteurs ÔÇö say, LindelofÔÇÖs idol David Lynch ÔÇö had never needed to reckon with. Namely, for Lost, what is this mysterious, magical island that the characters find themselves on? When its 2010 finale failed to produce answers, LindelofÔÇÖs rabid fan base turned on him. The groundbreaking series became a cautionary tale. Three years after the finale, LindelofÔÇÖs Twitter bio still read: ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm one of the idiots behind ÔÇÿLost.ÔÇÖ And no, I donÔÇÖt understand it, either.ÔÇØ He quit tweeting on October 14, 2013 ÔÇö the same date on which, in the pilot of his next show, 2 percent of the worldÔÇÖs population vanishes.

WATCH: Damon Lindelof explains The Leftovers finale.

It was Tom Perrotta who gave Lindelof a shot at redemption with his novel The Leftovers. A literary realist, Perrotta used the supernatural mini-Rapture as a catalyst for psychological and social turmoil. In return, Lindelof gave Perrotta almost equal say in his writersÔÇÖ room, and together they crashed the mysteries of existence into the hard limits of human relations. The author stayed on after season one exhausted his novelÔÇÖs plot, forming a partnership that remains rare even in the most prestigious Zip Codes of prestige TV. Despite anemic ratings, The Leftovers became a darling of viewers who prize dark subjects, wild invention, and the kind of intricate, recursive storytelling that rewards patient fandom.

One of the premises of The Leftovers was that the disappearance of the 2 percent, known as the ÔÇ£Sudden Departure,ÔÇØ gave spiritual seekers a do-over, a chance to write new testaments. So it was for Lindelof; PerrottaÔÇÖs humanism and HBOÔÇÖs focus on quality over quantity allowed him to channel his obsessions into a show that was more pedant-resistant (because the mystery was secondary) and easier to control. The Leftovers played out over three short, distinct seasons, the last one comprising eight episodes developed over twice as many months. Lindelof spent much of that time worrying about the last episode, No. 28, along with the inevitable comparisons to Lost. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs all that pressure of saying, ÔÇÿForget about your other 27 dives ÔÇö weÔÇÖve thrown out the scores,ÔÇÖÔÇëÔÇØ says Lindelof. ÔÇ£The only dive that matters is the 28th.ÔÇØ

What follows is the complete story of that dive, or rather three separate dives: ÔÇ£You make a show three times,ÔÇØ episode director Mimi Leder told me on that stormy night. ÔÇ£You script it, film it, and then you make it a third time in the editing room.ÔÇØ For this story, I spoke with everyone who was in the writersÔÇÖ room about the construction of the script; flew to Australia for a tense and emotional final week of shooting; and sat in with Lindelof as he built his final cut, reshaping his creation virtually frame by frame. Throughout, Lindelof was precise and obsessive. But the only thing he couldnÔÇÖt control was what the audience would make of it.

1.

HOW TO WRITE A SERIES FINALE

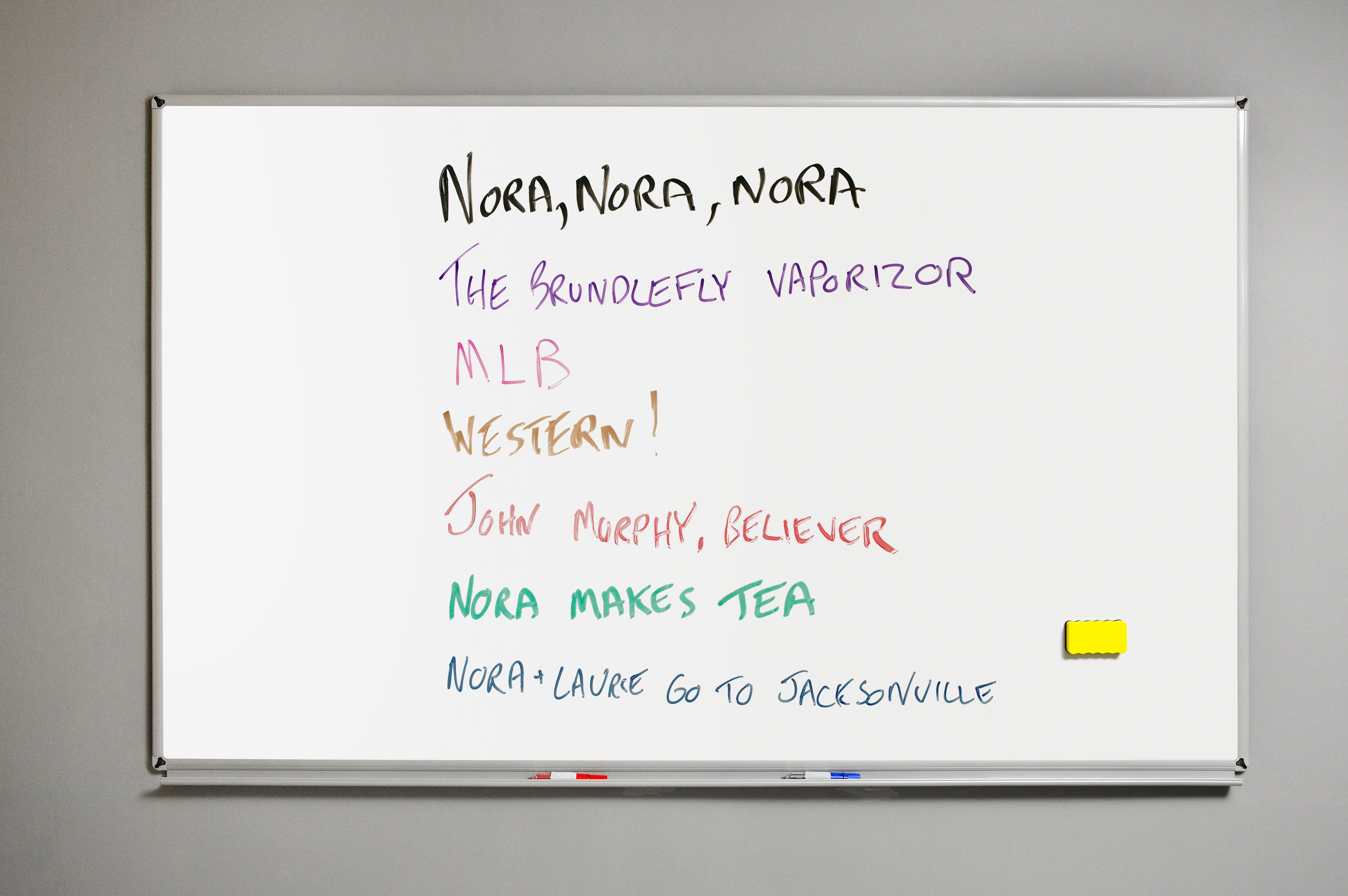

In the beginning was the whiteboard, and the first words written upon it were ÔÇ£Nora, Nora, Nora.ÔÇØ It was January 2016, a month after HBOÔÇÖs announcement of a final season. Lindelof gathered his season-two writers to spitball ideas over two weeks of ÔÇ£pre-roomÔÇØ meetings. The site was a couch opposite the whiteboard in LindelofÔÇÖs tchotchke-stuffed office at Lantana, a production complex in Santa Monica.

The three Noras refer to Nora Durst, who lost her husband and both of her children in the Sudden Departure, and whom Carrie Coon plays with dissociated ferocity. ÔÇ£SheÔÇÖs the ground zero for the departure,ÔÇØ Lindelof explains, sitting on th

e same couch nine months after those early blue-sky meetings. Giving her closure on her grief ÔÇ£felt like the perfect conclusion to the entire opus.ÔÇØ Even before the ÔÇ£pre-room,ÔÇØ he and HBO had agreed that the central journey of the season, and perhaps the whole show, would be NoraÔÇÖs. But when he wrote her name on the whiteboard, Lindelof wasnÔÇÖt sure how her journey would actually end.

This is where it starts: The LeftoversÔÇÖ first season follows police chief Kevin Garvey (Justin Theroux) in the lead-up to the Sudden DepartureÔÇÖs third anniversary in Mapleton, a New York suburb proliferating with would-be prophets (KevinÔÇÖs psychotic father; NoraÔÇÖs reverend brother, Matt) and nihilistic cults (like the silent, white-clad Guilty Remnant, for which KevinÔÇÖs wife, Laurie, left the family). After a dour ten episodes of visions, stonings, and flashbacks, during which Nora and Kevin become romantically entangled, the season ends in fires and riots. Kevin and Nora also find an infant on KevinÔÇÖs doorstep ÔÇö sheÔÇÖs the daughter of a cult leader. They adopt her and name her Lily in season two, which is bigger, better, and weirder than the first: The Garvey-Durst family move to Miracle, Texas, a town where no one departed and messianic fervor boils over, especially after three teenage girls mysteriously disappear. Their reappearance as Guilty Remnant members sparks more fires and riots.

Oh, and Kevin dies twice ÔÇö maybe ÔÇö and ends up in some kind of afterlife where he must complete a mission to come back to the land of the living. (The first time heÔÇÖs an international assassin and must kill a senator. The second time, he has to sing Simon & GarfunkelÔÇÖs ÔÇ£Homeward Bound.ÔÇØ) The stress of the Departure has hit Kevin in the form of bizarre visions, spirit-hauntings, and a subconscious death wish ÔÇô to which he responds not with his fatherÔÇÖs dead certainty but baffled ambivalence (along with experiments in self-asphyxiation). What he ultimately canÔÇÖt decide is whether heÔÇÖs a (possibly crazy) lone wolf or a family man.

For the final season, Lindelof started with only a few basic parameters. The action would move to Australia and take place on the cusp of the seventh anniversary of the original departure, when many people think the world might end. He and Perrotta had thrown around the idea that KevinÔÇÖs two returns from the dead might turn him into some kind of reluctant messiah for a group of believers, but beyond that Lindelof didnÔÇÖt have much.

The Leftovers is in a way the inverse of Lost: The interesting part isnÔÇÖt the mystery but how people live with it. Perrotta and Lindelof had toyed with some kind of apocalyptic ending, but even though The Leftovers begins with a cataclysmic unexplained event, the story hinges on the way humans respond to it; people are both the cause of and the solution to the post-departure chaos, so absolving them of their role via heaven-sent brimstone was off the table. In which case, how would a show obsessed with the End actually end? One possibility was to close with a man-made disaster. Both of the previous seasons had ended with social breakdowns. But they could also go the other way: The world doesnÔÇÖt end, and instead the characters must resolve the true underlying themes (grief, love, faith) on a personal scale.

There was another thread of the story to resolve, too, the question of the 2 percent. Where had they gone, and would their loved ones ÔÇö and the audience ÔÇö ever get to find out? Whether there was an answer, avoiding the question entirely might have suggested it didnÔÇÖt really matter ÔÇö and to the characters, at least, it really does. Lindelof was pondering these dilemmas late one night when he channel-surfed his way to David CronenbergÔÇÖs The Fly, in which Jeff GoldblumÔÇÖs character, Seth Brundle, is fused with a fly while testing a teleportation device.

Could something like that ÔÇö but much less sci-fi ÔÇö become the plot engine of NoraÔÇÖs deliverance? ÔÇ£The most obvious story,ÔÇØ Lindelof says, ÔÇ£is she gets a lead on where her kids are.ÔÇØ Nora is already a fraud investigator for departure-benefits cases. She could pursue scientists offering to send her to wherever the departed ended up. The twist is that she comes to believe that the scientistsÔÇÖ machine isnÔÇÖt a hoax, that it might actually send her to the Other Place. NoraÔÇÖs journey could dovetail with a stab at answering the Ultimate Question: Where did the 2 percent go? Lindelof added ÔÇ£Brundlefly Vaporizer,ÔÇØ his nickname for CronenbergÔÇÖs portal, to the whiteboard. ÔÇ£It scared Perrotta a little,ÔÇØ he says, ÔÇ£and that excited me.ÔÇØ

Perrotta had said adamantly and publicly that it didnÔÇÖt matter what happened to the vanished 2 percent, but he knew Lindelof was at least a little inclined to answer the Ultimate Question. One very Lost-ian idea the showrunner had clung to from the very first episode was the possible existence of a mirror world, where 98 percent of the population disappeared instead of 2 percent. While filming his pilotÔÇÖs first scene, during which a baby disappears from a car seat, Lindelof asked director Peter Berg if they could shoot an alternate version, ÔÇ£where we stay on the baby and then we tilt over to the front seat and the mother is gone.ÔÇØ Berg asked why. ÔÇ£That might be the way to end the series,ÔÇØ Lindelof had said. They didnÔÇÖt have time to film it.

But in that pre-room Lindelof revived the idea of showing the Other Place. ÔÇ£He made it so fucking compelling,ÔÇØ says Perrotta, ÔÇ£and everybody in the room is going, ÔÇÿYeah!ÔÇÖ And IÔÇÖm sitting there going, ÔÇÿNo!ÔÇÖÔÇëÔÇØ Lindelof, comparing his writersÔÇÖ room to 12 Angry Men, says that ÔÇ£Perrotta became Juror No. 8ÔÇØ ÔÇö the lone dissenter who brings the room around. Perrotta gave a version of his Leftovers stump speech: ÔÇ£It was always just a given for me that there is this mystery, the same mystery of where do we go when we die, and the idea that thereÔÇÖs one authoritative answer seems palpably ridiculous to me.ÔÇØ

Writer Patrick Somerville brokered a very Leftovers compromise: Nora tells the story of her visit to the Other Place to someone in the finale, sometime in the future, over a cup of tea. ÔÇ£But,ÔÇØ Lindelof countered, ÔÇ£if she tells it, then we wonÔÇÖt know if itÔÇÖs true!ÔÇØ Which, he realized in the middle of that sentence, is the perfect way to end the series: Give the audience an answer, but donÔÇÖt say whether itÔÇÖs true. And so they wrote a new phrase on that whiteboard: ÔÇ£Nora makes tea.ÔÇØ

Damon LindelofÔÇÖs Whiteboard

The decision to ÔÇ£let the mystery be,ÔÇØ as Iris DeMent sings over the finaleÔÇÖs opening credits, says much of what you need to know about Lindelof. He remains scarred by the backlash over Lost, but it didnÔÇÖt stop him from ending The Leftovers with an ambiguity the size of the universe, one that flirts with breaking PerrottaÔÇÖs implicit promise. ÔÇ£That all felt really delicious,ÔÇØ says Lindelof, ÔÇ£but I also kind of realized I was going to get crucifiedÔÇØ for once again leaving the audience guessing. He had come around to the idea that itÔÇÖs better to be memorable than cautious. ÔÇ£Twenty years from now, if people are still talking about The Leftovers in any context, even as a cautionary tale, thatÔÇÖs a huge accomplishment.ÔÇØ

The question of whom Nora would tell her story to was tabled for the real writersÔÇÖ room. For the time being, they settled on the teenage version of Lily, NoraÔÇÖs adopted daughter. Lily was a problem from the start ÔÇö itÔÇÖs not easy for a film crew to take a toddler to Australia ÔÇö so the pre-room agreed to have Nora lose Lily to her birth mother, reinforcing her alienation. Lindelof referred to nagging problems thereafter as ÔÇ£a Lily.ÔÇØ

As January turned to February, Lindelof staffed up his writersÔÇÖ room. He took a casual approach, inviting candidates for a conversation and seeing where it went. In the end, each writer brought his or her own particular set of skills: Lindelof was both the boss and the chief thrower of bombs, crazy ideas that Somerville calls ÔÇ£Damon grenades.ÔÇØ (ÔÇ£Laurie shoots herself!ÔÇØ) Perrotta was the critic with veto power. (ÔÇ£No other place!ÔÇØ) Tom Spezialy, an executive producer involved in all phases of production, was chief of staff and quality-control officer. Early each season, Reza Aslan, the religion scholar, came in to talk about IsaacÔÇÖs sacrifice or Aboriginal songs. (He insisted Kevin was a shaman and had to die.) Somerville, also a respected fiction writer, was the conciliator, the literary bridge between Lindelof and Perrotta.

On most TV dramas, episodes are sketched out in meetings and then assigned to one or two writers, but the Leftovers writers worked out almost every beat in the room, sometimes down to precise dialogue. Then at night the writers had homework: Invent a wedding ritual incorporating an animal; bring in an idea for a meaningful tattoo. ÔÇ£Writing by committeeÔÇØ has a bad rap, but on LindelofÔÇÖs jury, ÔÇ£the more traditional ideas are the ones that end up dying because theyÔÇÖre divisive,ÔÇØ says Somerville. ÔÇ£You have to get into some weird shit to find the one that unifies everybody.ÔÇØ

Photographs (Above): Patrick McMullan (Lindelof, Aslan, Perrotta); Courtesy of the subjects (remaining)

In February, the writers congregated around a table at Lantana to begin blocking out the rest of the season. All eight episodes were reverse-engineered from ÔÇ£Nora makes tea.ÔÇØ From the very first episode, whose coda is a flash-forward to NoraÔÇÖs last day, the writing process was an arrow aimed at the finale.

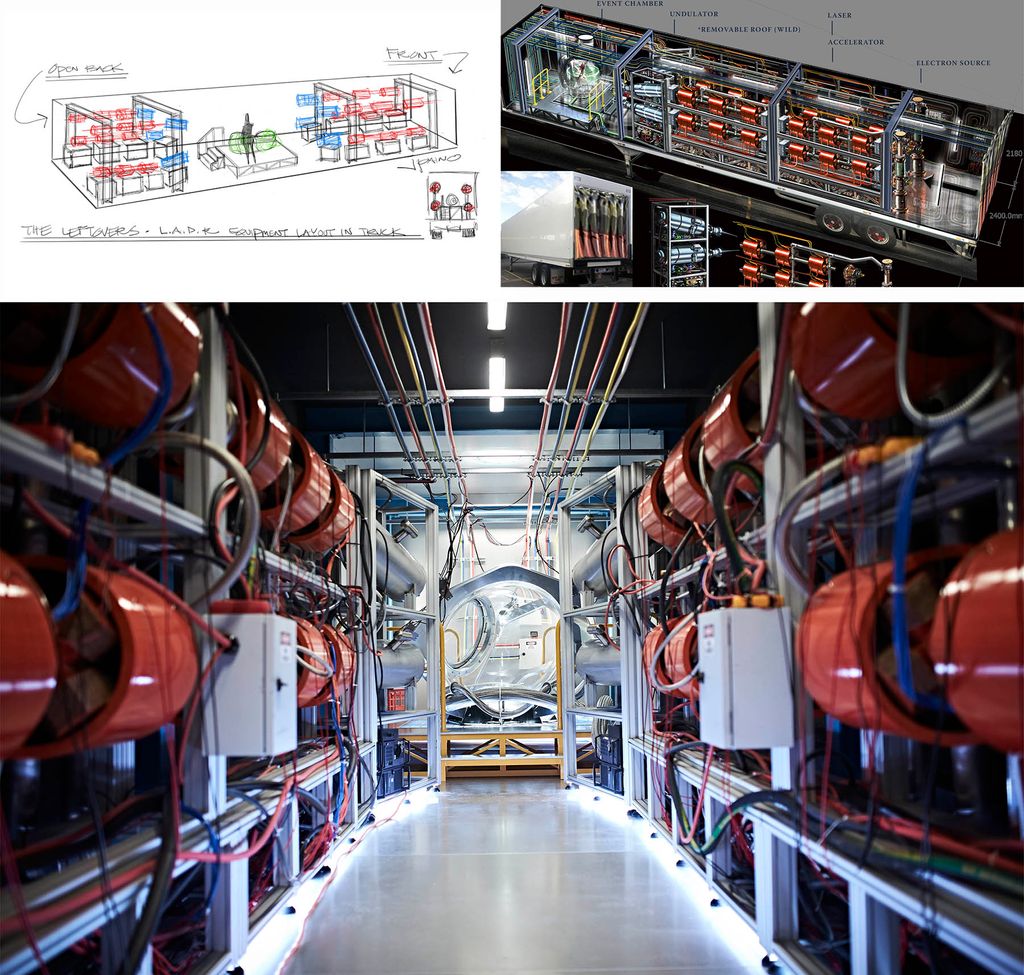

The final season opens with a preamble ÔÇö a historically accurate Australian branch of the 19th-century Millerites, waiting for a thrice-predicted Rapture that never comes. Then weÔÇÖre back in Miracle, two weeks before the seventh anniversary, which some residents believe might be the end of the world. (One interpretation of the Bible holds that after the Rapture of the faithful, there are seven years of tribulation followed by Armageddon.) End-times fever spreads as far as Australia, where the cast travels to become, more or less, fanatics. A Book of Kevin has been written about KevinÔÇÖs death-journeys by Matt and other ÔÇ£disciples,ÔÇØ who persuade Kevin to die once more; KevinÔÇÖs crazy father is already in the outback stealing Aboriginal songs to stop the coming flood; and finally and most importantly, Nora hears about a device that could zap her to the place where her family went (though the scientists admit they donÔÇÖt know where that is; they might be corpses floating in space). Kept on a truck to evade authorities and currently in Australia, the device generates ÔÇ£LADRÔÇØ (for Low-Amplitutde Denzinger Radiation), pronounced ÔÇ£ladder,ÔÇØ though itÔÇÖs almost never referred to by name on the show. After Nora flies to Australia to meet the scientists, they reject her without explanation, which only makes her more determined to go through. Kevin starts having visions again, the couple have a huge, relationship-ending fight, and Nora leaves him to hunt down the scientists.

As the writers began writing the season, NoraÔÇÖs companion for tea became obvious. Somerville remembers summarizing the first episode for HBO by explaining that the show was ÔÇ£a love story in reverse.ÔÇØ Kevin and Nora had been papering over profound unhappiness, pretending to know each other better than they did. ÔÇ£If you donÔÇÖt do the emotional work,ÔÇØ says Somerville, ÔÇ£itÔÇÖs going to catch up with you.ÔÇØ The finale had to be about that work, and the last conversation had to be between Kevin and Nora.

Working through the episodes, the writers also realized the season already had all the action it needed. For the finale, the world wouldnÔÇÖt end with a whimper or a bang; it would go on. The season-two finale hinged on a fake bomb threat. This season they could double down by violating what Lindelof calls ÔÇ£ChekhovÔÇÖs apocalypse.ÔÇØ Armageddon will come, but only for Kevin in his final death-world jaunt; on Earth, it just stops raining. The last line of the penultimate episode is spoken by Kevin Sr., up on a roof like the disappointed Millerites: ÔÇ£Now what?ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£This show is not about something happening,ÔÇØ Lindelof says. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs about the anticipation, and then the Great DisappointmentÔÇØ ÔÇö the textbook name of the MilleritesÔÇÖ nonevent. ÔÇ£And if we resolve [the idea the world might be ending] in the penultimate episode, the audience will have a full week to deal with the idea that we still have more show. And what we are really interested in ÔÇö the ÔÇÿnow what?ÔÇÖ of it all. What generates apocalyptic thinking is that you donÔÇÖt have to deal with the future.ÔÇØ The finale takes us ten years into that future.

The next few months went by in an episodic blur, with a long break in June so Lindelof could oversee production of the middle episodes in Australia. The biggest writing challenge was to find interesting ways (like an orgy on a ferry) to move every character toward his or her final moments, no loose ends allowed.

The writers met again in July to hash out details of the finale. But the first day or two of writing it were snagged, instead, on a character in plot purgatory. While meeting on episode six, Lindelof had dropped a Damon grenade: He sort of killed off Laurie. Some writers adamantly opposed her suicide; others thought it was time to sacrifice a character. ÔÇ£I didnÔÇÖt see it as part of LaurieÔÇÖs story,ÔÇØ says Haley Harris, a young writer who was driven to tears over the plot turn. Somerville and Carly Wray, another senior-level writer, were also against it. Then Nick Cuse, LindelofÔÇÖs ally in bomb-throwing, came up with the notion of scuba diving; he had a relative who had died of an embolism after a dive. A scuba-diving mishap, in which, say, Laurie cuts off the flow of oxygen from her scuba tank, could be a way of ÔÇ£camouflaging suicide,ÔÇØ relieving family members of the burden. Or, alternately, it could ÔÇ£push the debate onto the audience,ÔÇØ says Wray. But what it really did was push the question of LaurieÔÇÖs fate into the last episode.

Several writers only agreed to the scuba scene on the guarantee that Laurie was actually alive. Others felt that her survival would amount to a cheap twist ÔÇö ÔÇ£schmuck bait,ÔÇØ as Somerville called it. ÔÇ£By day two, morale was very low,ÔÇØ Lindelof remembers. ÔÇ£Also, I didnÔÇÖt want to be in the room. It just felt like there was a weight there. I think it was separation anxiety. ItÔÇÖs the final episode.ÔÇØ Finally, he realized he had to break the logjam. He stepped into PerrottaÔÇÖs office and said, ÔÇ£I think Laurie should still be alive.ÔÇØ Perrotta came around, and they went into SpezialyÔÇÖs office. ÔÇ£And then,ÔÇØ says Lindelof, ÔÇ£the three of us went into the room united, and it was a tremendous relief, and that was the day that everything changed.ÔÇØ

13 WORKS THAT INFLUENCED THE LEFTOVERS FINALE

But for Lindelof, the weight of ending his series never really lifted, ÔÇ£and I made everybody suffer for it,ÔÇØ he says. ÔÇ£Especially when they would pitch something that made it seem like, ÔÇÿAre we in some sort of alternate space?ÔÇÖ IÔÇÖd be like, ÔÇÿWeÔÇÖre not fucking doing that. No. Because IÔÇÖm going to have to be the one who answers the questions.ÔÇÖÔÇëÔÇØ

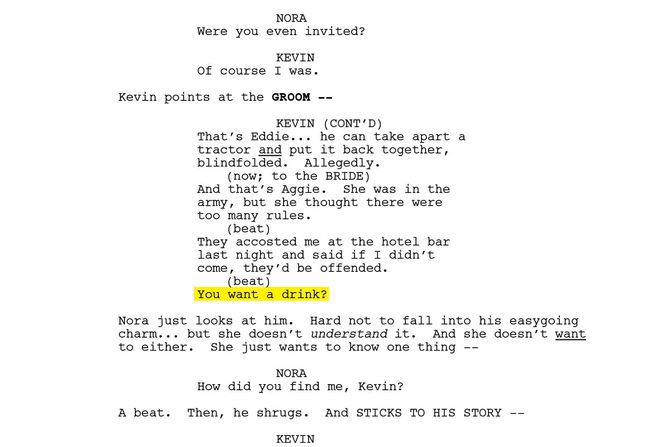

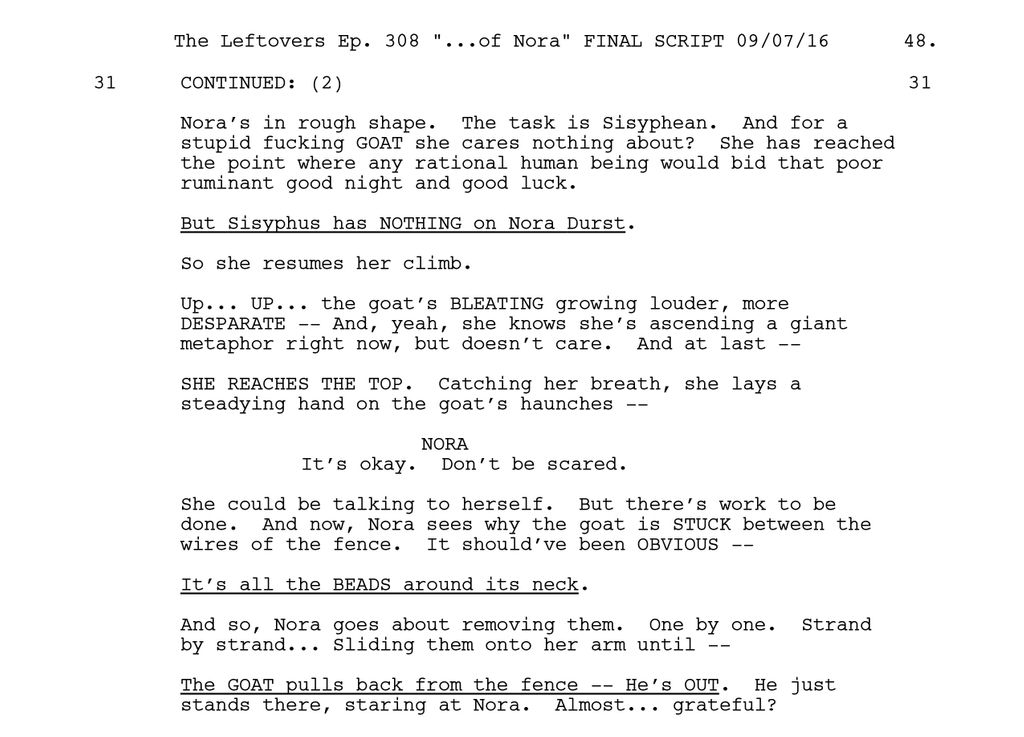

Before she maybe-dies in episode six, Laurie helps Nora track down the scientists. At the beginning of the finale, Nora is sitting outside the LADR truck, her last moments before entering the machine that will take her  somewhere, or nowhere. Inside the truck, the scene is mostly dialogue-free. But there are plenty of script directions; Lindelofs tend to be almost freestanding vignettes, complete with metaphor, rhythm, and profanity. And so, the LADR sequence reads, she walks toward it. Slow and deliberate  but without hesitation  she walks the entire length. A bride coming down the aisle. A prisoner approaching the electric chair. Or just a woman. Ready to be fucking DONE with a place that reminds her how deeply sad she is. Then, a page later, the mysterious moment where she maybe chickens out: And she OPENS HER MOUTH, ALMOST AS IF SHES ABOUT TO SHOUT SOMETHING at the TOP OF HER AIR-STARVED LUNGS and WE  SMASH TO BLUE.

Now what? How does Kevin find Nora, and what does he say to her? ÔÇ£There needed to be an organic stall that thematically made sense,ÔÇØ says Somerville. After Nora enters the LADR, the show jumps ten years. She is living alone in the Australian countryside when Kevin finds her. Somerville pitched Kevin telling her a lie ÔÇö a neat foreshadowing of NoraÔÇÖs own (made-up?) story at the end of the episode. ÔÇ£I had him introducing himself as, like, Bill Smith,ÔÇØ says Somerville, ÔÇ£and then Damon made it better: ÔÇÿNo, heÔÇÖs presenting as Kevin, but as a Kevin who hasnÔÇÖt seen her since that moment in season one.ÔÇØ The school dance where they met. Later, Kevin will confess angrily that playing dumb was a desperate gambit, and that in fact heÔÇÖd spent the last decade looking for her. Then she will make him tea and tell him where sheÔÇÖs been all this time.

Other scenes were worked out piecemeal: They wrote a goat into the wedding scene, as part of a made-up ritual in which guests unburden their sins onto the beast. Later he gets stuck in a fence and Nora wrestles to free him. ThereÔÇÖs a scene in which sheÔÇÖs at home alone, processing KevinÔÇÖs return; she gets locked in the bathroom, and must break down the door, symbolizing her own breakthrough. Earlier, she bikes to a pay phone to call Laurie ÔÇö who is alive! ÔÇö demanding to know whether Laurie is the one who tipped Kevin off. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs my favorite kind of storytelling,ÔÇØ says Lindelof, ÔÇ£where youÔÇÖre completely behind the story for 20 minutes and you catch up with it right around the time the emotion starts to kick in.ÔÇØ Between Laurie on the phone and Kevin and Nora talking, we also learn the fates of all the other characters. ÔÇ£There were many times over the course of the finale where I would say, ÔÇÿI do not want to spend the next 20 years of my life getting asked what happened to John Murphy.ÔÇÖÔÇëÔÇØ

This is how Damon Lindelof writes script directions.

Playing out SomervilleÔÇÖs reverseÔÇôlove story meant sending Kevin and Nora on a date. ÔÇ£TheyÔÇÖd skipped courtship,ÔÇØ Somerville says, ÔÇ£all those first steps and first dates,ÔÇØ and now KevinÔÇÖs lie allows them to start over and maybe fall in love for real. Nick Cuse suggested Kevin and Nora should go to a wedding together. ÔÇ£I was thinking about this time when I was in love with this girl I had dated, and I was devastated,ÔÇØ says Cuse. ÔÇ£I was in my parentsÔÇÖ kitchen and the wedding scene from Up in the Air was playing, when Vera Farmiga and George Clooney are dancing, and I had this feeling of broken-heartedness and weeping.ÔÇØ He realized how fraught other peopleÔÇÖs weddings could be for a couple ÔÇö how effective at surfacing buried emotions. Kevin invites Nora to a dance, and she arrives to find out itÔÇÖs actually the wedding of two local townspeople.

Plotting out what happens after the wedding required what Lindelof calls ÔÇ£a very late night figuring out how Nora has shifted and sheÔÇÖs ready to tell the story.ÔÇØ Even though the story itself was sketched out months earlier in the pre-room, Lindelof actually sat down to write it while in Australia prepping for episode seven. By then, the room had reached a verdict on whether NoraÔÇÖs story is true. ÔÇ£We have a unanimous feeling as to which one of those realities is real and we will never, ever, say, ÔÇÿThis is what really happened,ÔÇÖÔÇëÔÇØ says Lindelof. ÔÇ£Kevin believes, or says he believes, the story; thatÔÇÖs the whole point of the series. ThatÔÇÖs what religion is.ÔÇØ

2.

HOW TO FILM A SERIES FINALE

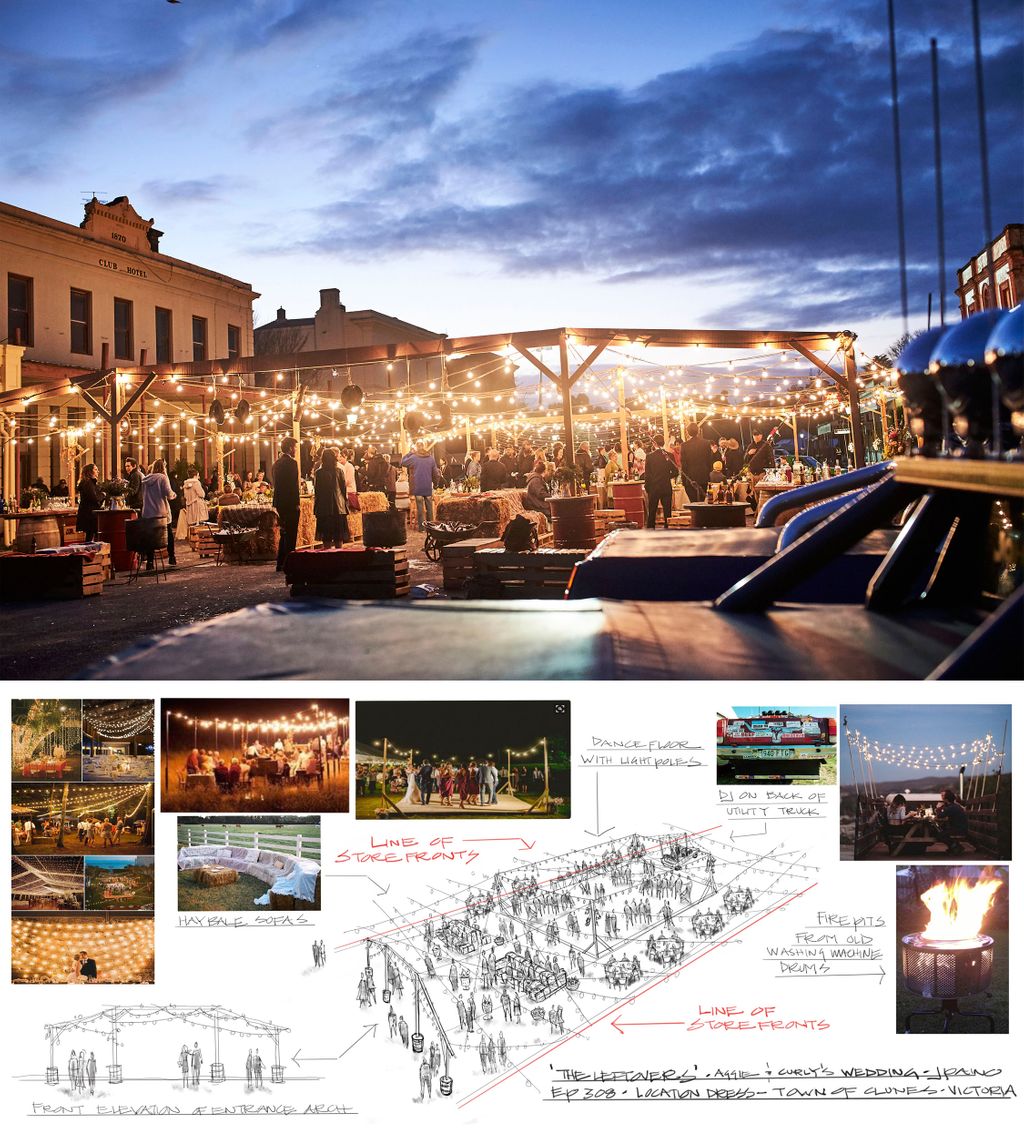

ÔÇ£Why does God hate us?ÔÇØ Mimi Leder moans as the drizzle starts to thicken over the Australian gold-rush ghost town of Clunes, dampening the set of a large and motley wedding: golden lights strung low over a wooden platform in the middle of Fraser Street; 150 shivering extras in light tuxes and strapless dresses; an impassive white goat the size of a Great Dane, warmed by a Peruvian-style blanket. Leder watches from the dry warmth of ÔÇ£Video Village,ÔÇØ a bank of monitors and folding chairs behind a storefront window marked ÔÇ£Sunday Special, $25 Roast.ÔÇØ

A few hours ago, a hazy moon hung over the scene, but at three in the morning, brief cloudbursts force Margie Beattie, the first assistant director, to corral the extras in and out three times, shouting, ÔÇ£Safe hair!ÔÇØ In drier moments, a visual-effects specialist takes light measurements near a cage full of pigeons so he can make them rise majestically in postproduction. By the standards of HBO and even The Leftovers, itÔÇÖs a laid-back scene, but in the context of this intimate finale, it feels Felliniesque ÔÇö especially when Leder steals a line from the groom: ÔÇ£Bring out the fucking goat!ÔÇØ

From hay-bale sofas to washing-machine fire pits and golden lights that the groomsmen would have hung up themselves, no detail was too small for production designer John Paino and his team to sweat over. They aimed to manufacture a kind of ÔÇ£hipster ÔÇÿboganÔÇÖ weddingÔÇØ (bogan being Australian slang for hillbilly). They also borrowed from the Australian culture of bachelorsÔÇÖ and spinstersÔÇÖ balls, where singles in formalwear and cowboy boots dance surrounded by custom-designed ÔÇ£utesÔÇØ (pickup trucks). The only element cut from PainoÔÇÖs detailed sketch was the DJ on the back of a utility truck, nixed for poor sightlines. Paino didnÔÇÖt mind: ÔÇ£The best thing you can do is have so much stuff there that itÔÇÖs like a buffet for the director.ÔÇØ

NoraÔÇÖs speech to Kevin over tea is the culmination of not only her grief pilgrimage but also their love story, and the wedding, that long-deferred first date conjured by the writers, is where they start rebuilding their connection. The power of their final scenes depends on their tense conversation here. Like the story Nora tells Kevin over tea, the setting of this reunion entailed months of planning and years of dreaming. Lindelof didnÔÇÖt think of Australia for The Leftovers until Tom Spezialy joined the show in season two. Spezialy is obsessed with Australian auteur Peter Weir, whose Picnic at Hanging Rock, about vanished schoolgirls, inspired the plotline of season twoÔÇÖs faked departures.

While Lindelof was kicking off the writersÔÇÖ room in February, producer Gene Kelly, who manages the budget, went on a location tour with Leder, Spezialy, and production designer John Paino. One stop on that tour, led by AustraliaÔÇÖs film commission, was Clunes. Spezialy called Lindelof in L.A. and told him theyÔÇÖd found the area where Nora should end up. It had everything: a historic town with a real main street surrounded by isolated, open hills. Later, the producers found the perfect cottage for Nora there. Owned by an eccentric artist, it was hand-built with leaded windows, a slim concrete chimney, and walls of gray stone and milled eucalyptus. It was also ÔÇ£very cluttered and full of cats,ÔÇØ says Leder. After paying the owner to rent it, Leder and Paino oversaw a complete renovationÔÇöclear windows, a smaller kitchen counter, and a fake second bathroom.

WHERE THEY SHOT SEASON THREE

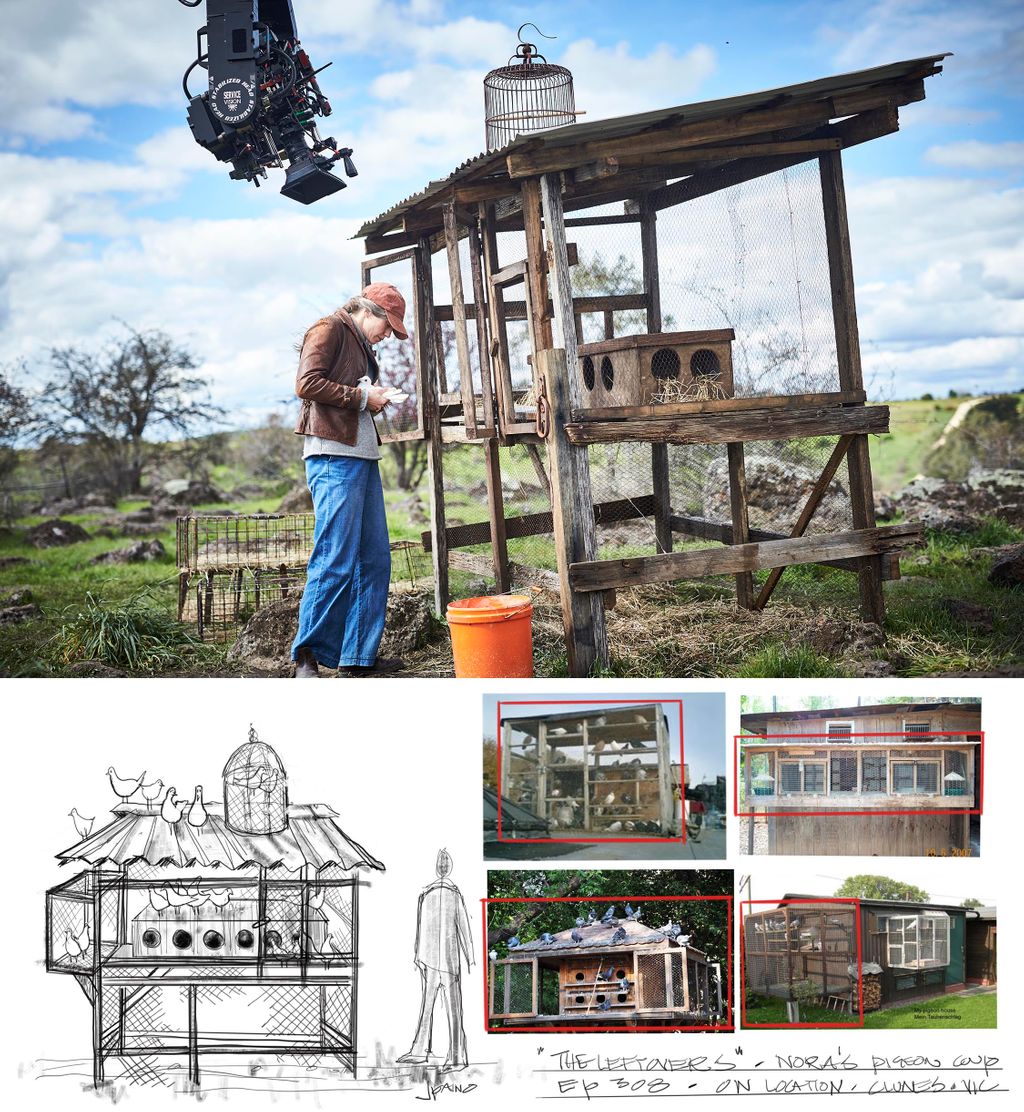

Meanwhile, Paino began researching the finaleÔÇÖs design. Some of his best ideas came from the location itself. The Australian crew told him about ÔÇ£bachelors and spinsters ballsÔÇØ ÔÇö rowdy parties featuring outlandish formal getups and customized ÔÇ£utes,ÔÇØ or pickup trucks. (Think of a rave mashed up with a truck rally and a Mad Max fan convention.) Scouting outside Sydney, they had discovered a 100-year-old pigeon coop. It inspired the writers to have Nora breed pigeons in her new life. The writers even wrote the birds into the wedding, supposedly carrying guestsÔÇÖ messages out into the world (though they actually just returned to Nora).

Just as The Leftovers thrives on the push-pull of LindelofÔÇÖs mania and PerrottaÔÇÖs groundedness, it lives in the space between the writersÔÇÖ Talmudic precision and Mimi LederÔÇÖs scenic experimentation. Most TV shows rotate through a stable of directors, and so did this one, but Leder was first among equals. The Leftovers was wallowing in darkness through the middle of season one, visually and emotionally, until Leder was hired. She opened it up to contrast, humor, and hope. In his farewell speech on the set, Lindelof called her ÔÇ£our fearless leader, who came in and basically saved the show.ÔÇØ

For the pigeon coop, the set designers wanted to replicate the aesthetic of NoraÔÇÖs houseÔÇöquirky and handmade out of incongruous found parts. ÔÇ£Someone whoÔÇÖs handy made it out of scrap wood,ÔÇØ Paino imagines, ÔÇ£so it feels almost like itÔÇÖs part of the house.ÔÇØ ThereÔÇÖs even a separate birdcage stuck on to the top. ÔÇ£I was hoping that two birds would find their way up into that part,ÔÇØ says Paino, ÔÇ£but they never did on set.ÔÇØ

A strong director is especially essential on a series whose creator has zero interest in directing. ÔÇ£We would never leave,ÔÇØ Lindelof says, if he were running a set. ÔÇ£IÔÇÖd need to have one perfect take, instead of realizing weÔÇÖll have all the options in the cutting room.ÔÇØ Leder, a veteran of TV and film (ER, Deep Impact), is decisive, direct, and calm. Her emotional range over my week on the set span from mild disappointment to a sort of ecstatic serenity.

ÔÇ£When she first came in,ÔÇØ says Justin Theroux, ÔÇ£there were crew members who were kind of like, ÔÇÿThatÔÇÖs not how we do things around here.ÔÇÖ She was like, ÔÇÿI donÔÇÖt give a fuck.ÔÇÖ She just basically grabbed the thing by the back of the neck and started directing the shit out of it.ÔÇØ Leder can push actors hard (ÔÇ£Do it againÔÇØ is her constant, occasionally wearying refrain), but her tone is more persistent than aggressive.

At the Clunes wedding shoot, her persistence plays out for hours. ÔÇ£The problem is you have the luxury of too many hours tonight,ÔÇØ Theroux says after one too many takes of the dance. ItÔÇÖs a problem Leder loves to have. She even lavishes attention on Rupert ÔÇö the goat. Leder had rejected a smaller, pre-trained goat, so Rupert had to be found and brought up to speed in a week. ÔÇ£The first day on set, he got worried about things,ÔÇØ says Cody Harris, an animal trainer who looks like Will Forte playing Crocodile Dundee. ÔÇ£And then he got good.ÔÇØ

Lead the goat, Leder says, instructing Chris Cuevas on the A-camera to follow Rupert with a handheld, wide-lens Steadicam. A longtime Leder collaborator, Cuevas is one of very few American Leftovers crew members to be flown over to Australia. After Cuevas shoots Rupert receiving guests Mardi Gras beads, Leder triumphantly yells And  cut, smiling beatifically. This show is so much about subtext and symbolism, she says. You need to find ways of bringing that out.

Of all the elements in this circus, Leder is most concerned with capturing Kevin and NoraÔÇÖs tricky courtship. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs a really hard note to hit narratively,ÔÇØ she says. ÔÇ£It was kind of an easy thing to write, but itÔÇÖs a much harder thing to play.ÔÇØ Most of LederÔÇÖs experiments attack that challenge. While shooting NoraÔÇÖs emotional dance with Kevin, they try a take without any extras, so that it might look like the guests have disappeared. Soon Cuevas is circling the lovers on an empty platform, his shirttail held by an assistant keeping him clear of obstructions. Leder is delighted, ÔÇ£but who knows, maybe we wonÔÇÖt use any of it.ÔÇØ After that, a long, telescoping crane pulls up to the edge of the wedding, dangling a camera that stays close in on NoraÔÇÖs face as she stomps off the dance floor, leaving Kevin receding behind. ÔÇ£This is fucking beautiful,ÔÇØ says Leder. ÔÇ£Damon will hate it,ÔÇØ she half-jokes. It might be too showy for his taste.

Lindelof, Spezialy, and Perrotta werenÔÇÖt there for the wedding; they only fly in for the last week of filming, when Leder shoots the two most important scenes: the final conversation and NoraÔÇÖs entrance into the LADR, which opens the episode.

The pressures of the wedding scene are trivial compared to ÔÇ£Nora makes tea.ÔÇØ That shoot is so predictably tense that I am not allowed on set. There isnÔÇÖt much room in the cottage, but more important, the actors felt vulnerable. Lindelof meets me the next morning in the dining room of a golf resort a half-hour from Clunes, the closest place that could accommodate a film crew. HeÔÇÖd flown in from L.A. and gone directly to the set, but it isnÔÇÖt just jet lag showing on his weary, stubbled face.

ÔÇ£Yesterday morning felt very quiet, very calm, very sad,ÔÇØ he says. ÔÇ£I was trying to put aside my expectations for the scene and just be there. But the prevailing emotional sentiment that started to push through the day was: How big of a deal is this ÔÇÿDo I believe her or notÔÇÖ thing gonna be? If I could build a machine that could tell people how to think, it would essentially be that 50 percent of the people believe that what Nora is saying happened and 50 percent think sheÔÇÖs making this up, but all 100 percent say it doesnÔÇÖt matter.ÔÇØ

The tension felt different for everyone that day. Leder reversed the order of the monologues: NoraÔÇÖs show-closing conversation would be shot first, KevinÔÇÖs angry confrontation, in which he demands to know what happened to Nora, second. There were compelling technical reasons for this: It would be sunnier for the exterior scene, and shooting it sequentially would have forced a two-hour makeup break as opposed to 20 minutes. ÔÇ£The ideal situation would have been to shoot it the other way,ÔÇØ says Leder, ÔÇ£but it didnÔÇÖt seem right to break up the most emotional, final scene into two days.ÔÇØ

THE LEFTOVERS ÔÇÖ FOUR FAVORITE CAMERA TRICKS

Any show with a distinct sensibility has a lexicon of preferred camera styles, directions, and angles. The Leftovers is influenced by a combination of Mimi LederÔÇÖs eye; the tools and skills of her cameraman, Chris Cuevas; and Damon LindelofÔÇÖs desire to get inside a characterÔÇÖs head without becoming too ÔÇ£camera-aware.ÔÇØ Four of their favorite camera shots featured heavily in the finale:

THE HANDHELD STEADICAM Good for closely following a chase scene or getting extra-intimate during a close-up.

THE LONG-FOCUS LENS The center of attention is in focus, and everything else is blurred out and far away.

THE CRANE SHOT Hanging the camera off the end of a long, low crane that telescopes rapidly can make a character seem to recede or advance against the backdrop.

THE ÔÇ£DIRTY-OVERÔÇØ Medium shots of talking faces over someoneÔÇÖs shoulder reinforce the connection between two characters.

Coon had been preparing for weeks. Trained in theater, she knew that ÔÇ£the only way to have freedom in the moment is to be really solid on the lines.ÔÇØ It helped that sheÔÇÖd been living with Nora for three years. ÔÇ£I have a lot of visual memory from working with those kids in season one,ÔÇØ she says, referring to the episode where NoraÔÇÖs children disappear. ÔÇ£IÔÇÖve lived through a lot of her life, her more traumatic times.ÔÇØ

Coon had broken down the story into four tonal sections, as suggested by LindelofÔÇÖs script directions. It isnÔÇÖt very long, but it ends the series, and it constitutes either the sincerest kind of lie ÔÇö the lie we tell ourselves in order to live ÔÇö or the most improbable and shocking truth.

ÔÇ£I didnÔÇÖt change my mind,ÔÇØ Nora tells Kevin, ÔÇ£I went through.ÔÇØ She pauses. ÔÇ£I was in the parking lot. Naked, curled up like a baby,ÔÇØ as sheÔÇÖd been in the LADR. Eventually she met a woman whoÔÇÖd lost her entire family. ÔÇ£ThatÔÇÖs when I understood. Over here, we lost some of them, but over there? They lost all of us.ÔÇØ She found her own family in mirror-Mapleton, complete with a new mother. Nora was ÔÇ£a ghost who had no place there.ÔÇØ So she found her way back ÔÇö but not to Kevin. ÔÇ£Did I think about you? Did I want to call you,ÔÇØ she asks Kevin. Of course, but it was too late, and she thought heÔÇÖd never believe her. ÔÇ£I believe you,ÔÇØ he says. ÔÇ£Why wouldnÔÇÖt I? YouÔÇÖre here.ÔÇØ

After CoonÔÇÖs second take, Lindelof turned to Perrotta and said, ÔÇ£I think I believe her.ÔÇØ At the hotel he tells me, ÔÇ£LetÔÇÖs say you wrote something that you knew was not true, but then somebody else recites it and they believe it. Does that make it true?ÔÇØ He adds that he and Coon ÔÇ£have very purposefully avoided the subjectÔÇØ of whether or not Nora really went through.

Running through takes, Leder and Coon worked on modulating the performance, varying the moments where she burst into tears. ÔÇ£Carrie is a super-honest actor,ÔÇØ says Leder, ÔÇ£and she feels every moment to the core. Sometimes itÔÇÖs a matter of pulling back.ÔÇØ According to Coon, ÔÇ£the thing Mimi always comes up to me with is, ÔÇÿThatÔÇÖs great. Now fight against it.ÔÇÖÔÇëÔÇØ She compared the required restraint to the trick of playing drunk. ÔÇ£Drunk people arenÔÇÖt trying to be drunk. TheyÔÇÖre trying to pretend theyÔÇÖre not drunk.ÔÇØ

How They Made Kevin and Nora Look Older (But Not Too Much Older)

Leder aimed the cameras only at Coon for the first set of takes; the next round captured TherouxÔÇÖs reactions, forcing Coon to tell it all over again and Theroux to respond as if hearing it for the first (instead of fifth) time. Then, finally, the action moved to the backyard for KevinÔÇÖs confrontation. Theroux became increasingly annoyed with his own performance, and he second-guessed LederÔÇÖs reversal of the shoot. ÔÇ£It was just tough,ÔÇØ he tells me a few days later. ÔÇ£Fucking Carrie just crucified it so good, and then we were fighting the light at the end of the day. I got a bit stony on the speech. I was tired. The sun was setting. The pressure was on. I didnÔÇÖt love that day.ÔÇØ

Lindelof says TherouxÔÇÖs angst made his performance stronger. ÔÇ£Because JustinÔÇÖs scene is pitched so high, I think the idea that we were losing the light actually helped [to play] a character frustrated and off-kilter.ÔÇØ

Fortunately, TherouxÔÇÖs last scene, three days later, is literally in a warm bath of good feelings. On a Melbourne soundstage on the last day of filming, he shoots a holdover from episode seven: a flashback to Nora and Kevin chatting in a bath tub. ÔÇ£It was a very nice way to go out,ÔÇØ Theroux tells me just after wrapping the scene.

The second scene shot that day, the last to be filmed in the entire series, is one of the most pivotal ÔÇö and expensive ÔÇö of the episode: Nora entering the LADR. For its design, the show consulted with a physicist, who shared images of supercolliders and retro nuclear-fusion machines. They settled on a transparent globe and clear water as the event chamber where Nora would be irradiated. It cost $100,000 and appears onscreen for three minutes.

Seeing it in person for the first time on set, Lindelof congratulates Paino on ÔÇ£your masterpiece. ItÔÇÖs like seeing photographs of the Mona LisaÔÇöand then you have to actually step into the Louvre.ÔÇØ

The ÔÇ£LouvreÔÇØ is an ersatz truck, a big box parked in the middle of an enormous soundstage. The inside walls are lined with orange spools strung with wires. At the far end is an acrylic bathysphere with a hatch on one side. There is an opening at the top for CoonÔÇÖs comfort and safety, which could be erased in postproduction. Inch-wide holes at the bottom can shoot water in ÔÇ£as fast as you want,ÔÇØ says a crew member, ÔÇ£though it might rip her skin off.ÔÇØ

Lindelof and Perrotta take turns posing inside the globe while Theroux takes pictures. ÔÇ£DonÔÇÖt Insta this!ÔÇØ Lindelof yells. ÔÇ£Spoiler alert! ItÔÇÖs not a sci-fi show, man!ÔÇØ He seems more worried about having his finale misinterpreted than spoiled. Shortly after he arrives, they turn off the eerie blue underlighting. ÔÇ£You just know sci-fi when you see it,ÔÇØ Lindelof explains. ÔÇ£Tom wrote a novel with a supernatural premise, but thereÔÇÖs a way to make this set look like Space Mountain and thereÔÇÖs a way to make it look like itÔÇÖs the Large Hadron ColliderÔÇØÔÇöif the particle accelerator were installed in a truck to evade authorities. ÔÇ£Once you put Carrie Coon in there, I think youÔÇÖll forget all the trappings.ÔÇØ

ThatÔÇÖs partly because Coon is going to be naked. ÔÇ£I felt it was very important to show her completely nude, frontally,ÔÇØ says Leder, ÔÇ£as a little girl standing there completely vulnerable in a full wide shot.ÔÇØ The soundstage is superheated for CoonÔÇÖs comfort (and no one elseÔÇÖs). Before disrobing, Coon, who is out of her older-age makeup, reads off NoraÔÇÖs ÔÇ£testimonialÔÇØ ÔÇö the video each LADR entrant leaves behind ÔÇö dispatching it in three takes. ÔÇ£Jesus, that was fucking great,ÔÇØ says Leder. ÔÇ£I donÔÇÖt know what to say to her.ÔÇØ From CoonÔÇÖs point of view, NoraÔÇÖs testimonial is evidence that sheÔÇÖs willing to go through. ÔÇ£On some level, it doesnÔÇÖt matter to her if itÔÇÖs real,ÔÇØ she says. ÔÇ£All that matters is that she can choose it, and if that means choosing suicide, so be it.ÔÇØ

Video Village is closed off with scaffolding and black curtains, and when Beattie shouts, ÔÇ£We are a closed set!ÔÇØ all nonessential crew are shuttled out to the catering area, where a gelato truck awaits. I am shuttled out too, but given a headset to listen in and allowed back in between takes. The sequence, mostly wordless, is more emotional in some ways than the closing conversation, and just as important to the viewerÔÇÖs idea of what happens after the ÔÇ£SMASH TO BLUE.ÔÇØ But it makes for a fussy shoot. Coon has to spend 20 minutes drying off after each take. Every time she closes the hatch the action has to stop for 30 seconds while technicians rivet the door shut. ÔÇ£That scene in the tub with Kevin and Nora, I was getting really choked up because it was the last time these two actors are working together,ÔÇØ says Lindelof. ÔÇ£But this is just, like, people wiping down plastic.ÔÇØ

Inside the truck itself, it is just Coon and Chris Cuevas. ÔÇ£Carrie, IÔÇÖm going to be physically closer when you first step in,ÔÇØ he says.

ÔÇ£CanÔÇÖt wait!ÔÇØ she says, joking but edgy. ÔÇ£Just watch it or youÔÇÖre gonna get some merkin in your teeth.ÔÇØ

When Coon emerges from a set of takes in a robe, Lindelof tells her, ÔÇ£Looking good.ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£Great,ÔÇØ Coon says with a smirk.

ÔÇ£I mean the way youÔÇÖre playing it!ÔÇØ he adds quickly. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs like youÔÇÖre seeing it for the first time.ÔÇØ

Leder is ready to try again: ÔÇ£They say ÔÇÿHappy to goÔÇÖ instead of ÔÇÿReadyÔÇÖ in Australia, right?ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm not happy,ÔÇØ says Coon, ÔÇ£but IÔÇÖm ready to go.ÔÇØ

Before they actually run the water through, Beattie tells Coon what to do if she panics in the machine. Simultaneously, Lindelof talks to me about religionÔÇÖs universal death wish: ÔÇ£A lot of people who take a religious journey start from a place of complete and utter cynicism, and for people who find belief systems later in life, thatÔÇÖs really interestingÔÇöÔÇØ

ÔÇ£So IÔÇÖll just let you know: Up here is open. So at any point that itÔÇÖs uncomfortable you can stand upÔÇöÔÇØ

ÔÇ£And all you really need is the right incentive, and the incentive of Christianity is the same incentive that the LADR offers, which is, you get to be with the people you love again. Judaism never stood a chance.ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£ÔÇöAnd thereÔÇÖll be someone right there and IÔÇÖll get you on the radioÔÇöÔÇØ

ÔÇ£YouÔÇÖre gonna see all the people that you loved and lost, youÔÇÖre gonna be pain-free, and youÔÇÖre gonna be with them for an eternity. Who doesnÔÇÖt want to get on that train?ÔÇØ

Leder and Coon try NoraÔÇÖs ambiguous final shot a couple of different ways. As she turns up for air, will she be gasping for a final breath, or splashing, or yelling something? ÔÇ£Our discussions were: LetÔÇÖs do it as if you are not going out ÔÇö at least up until the very last second,ÔÇØ Leder tells me later. ÔÇ£And then I did have her do takes where she does yell something, just to get that first syllable.ÔÇØ

Coon emerges from her final takes looking very energetic for two in the morning. We are minutes away from last good-byes. She takes a philosophical approach to the sequence. ÔÇ£If people are moved by it, theyÔÇÖre having whatever experience they want to have, and theyÔÇÖre going to believe Nora or theyÔÇÖre not, and itÔÇÖs going to reveal so much about them and nothing about me,ÔÇØ she says. Perrotta adds that they didnÔÇÖt have to figure it out just yet. ÔÇ£SheÔÇÖs trying to see which note is the right one. SheÔÇÖs definitely given us both versions to useÔÇØ ÔÇö cold feet and suicidal resolve ÔÇö ÔÇ£and weÔÇÖll see in the editing room which one makes sense.ÔÇØ

3.

HOW TO EDIT A SERIES FINALE

ÔÇ£So how do I get into NoraÔÇÖs head,ÔÇØ asks Lindelof, ÔÇ£and give the audience a more emotional experience?ÔÇØ Nearly three months after wrapping in Melbourne, weÔÇÖre in the Lantana office of the episodeÔÇÖs editor, Henk Van Eeghen, a tall Dutch man who, in one of the many inside jokes on the show, lent his name to the inventor of the device Nora is approaching on a large screen. Van Eeghen is the one behind the console who executes all the edits for Lindelof, but he also had first crack at the footage coming in from Australia. Two months ago he made an initial editorÔÇÖs cut, lining up the shots into a long approximation of a show. A few weeks after that, Leder submitted her directorÔÇÖs cut, making more aesthetic choices and temping music. And finally it came to Lindelof, currently about halfway into the two weeks that it will take him to change it slightly scene-by-scene and radically in its entirety.

At the moment, Lindelof is showing Spezialy the changes heÔÇÖs already made to the LADR scene. (Over two days I will see him edit about a third of the 72-minute finale.) Spezialy is here to offer a last note or two, which Lindelof always takes; he likes to say ÔÇ£Speez ColumboÔÇÖd usÔÇØ when the producer catches a last-minute flub. First, we watch the directorÔÇÖs cut, a somber and swelling affair. Leder scored NoraÔÇÖs walk to portentous atonal music, heavy on shots of the machine. It flirts with tropes Lindelof hopes to avoid. He wants to ground the scene more in lived reality, rather than some sci-fi genre space. ÔÇ£This is just straight up Nora is walking into this thing. SheÔÇÖs scared and itÔÇÖs scientifically overwhelming, but what is she thinking?ÔÇØ

Lindelof began by adding a shot on NoraÔÇÖs feet, ÔÇ£making it more of a procession.ÔÇØ He swapped in a wider take of the full frontal, so Nora looks smaller, ÔÇ£less physically naked and more emotionally naked.ÔÇØ More strikingly, the scene is now ÔÇ£dryÔÇØ ÔÇö no music at all. But a few steps in thereÔÇÖs a distant shout, which I mistake for children playing outside. ItÔÇÖs actually an aural flashback to the chaotic season-one vignette right before NoraÔÇÖs family disappeared. A boy chants, ÔÇ£I want food!ÔÇØ Nora says ÔÇ£Goddammit!ÔÇØ A cell phone buzzes. A quick flash of the kids appears before we cut back to her walk. Then there are the terrifying ticks of the machine, the fluid rushing up and, finally, Coon opens her mouth and starts to shout before the scene cuts. The final gasp is evidence that she chickened out; the flashes of memory are evidence she is determined to go through.

LindelofÔÇÖs cut is powerful, but a little disorienting. Spezialy praises the sound designÔÇöÔÇ£It keeps us out of a familiar genre language. My only thought,ÔÇØ he adds, Columbo-like, ÔÇ£is my brain got confused about what was happening in the room and what was remembrance.ÔÇØ So they add a few more visual flashbacks. ÔÇ£If I had my druthers,ÔÇØ Lindelof says, ÔÇ£there would be no picture [flashes] at all, just sound. Ninety percent of the audience would say ÔÇÿWhat is that?ÔÇÖ And 10 percent would say, ÔÇÿI love how understated it is.ÔÇÖ But you have to make the show for 100 percent of the people watching it.ÔÇØ

Like an airplane passenger attaching his own oxygen mask first, Lindelof has to please himself before entertaining others. Typically, he and Van Eeghen will watch a whole scene through, have a quick discussion, test new music if need be, and then dive in. About half the time, they go take-by-take, and if something feels off, Lindelof will say, ÔÇ£Line up the alts, Henk.ÔÇØ Van Eeghen then brings up every workable shot and they narrow it down like an optician: ÔÇ£Better or worse? Better or worse?ÔÇØ Some showrunners find this too tedious. ÔÇ£There are a lot of people in my position who donÔÇÖt like to be in the room; theyÔÇÖll give notes and leave,ÔÇØ Lindelof says. ÔÇ£I love this process. ItÔÇÖs painstaking ÔǪ ItÔÇÖs bird by bird: ÔÇÿI donÔÇÖt know how to fix this episode, but letÔÇÖs make this scene great,ÔÇÖ or ÔÇÿI donÔÇÖt know how to fix this scene, so letÔÇÖs make this line great.ÔÇÖÔÇØ

Connecting the viewer to Nora is one of Lindelofs editing imperatives. For one scene, he digs through discarded takes in search of more and longer eye contact, landing on one in which Coon opens her eyes after Leder yells Cut. Get in there man, get into those eyes, he tells Van Eeghen. (An editor can push in a shot up to 40 percent.) Even in the beautiful wedding sequence, Lindelof always favors Kevin and Nora over their picturesque surroundingsincluding Rupert. Not to say he doesnt love the goat. Ruperts looking straight into my soul right now, Holy shit! he says over a shot that makes the final cut. (He texts it to Theroux as a meme: I MISS YOU  KEVIN GAHAHAHAHAHAHRVY.) But the handheld wide-lens shot on Rupert that Leder used is scrapped. I hate any time Im aware of the camera, he says.

Another imperative is to lighten the tone. Earlier, Lindelof decided to ÔÇ£work against pictureÔÇØ by dropping in Billie HolidayÔÇÖs ÔÇ£The Man I LoveÔÇØ for the scene when Nora bikes to the wedding. ÔÇ£Billie is telling the audience, ÔÇÿThis is a love story.ÔÇÖÔÇØ Now, Lindelof tries a second Holiday song, ÔÇ£Back in Your Own Backyard,ÔÇØ for a later scene of Nora locking all the windows. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs manipulative but self-aware,ÔÇØ says Spezialy, ÔÇ£and thatÔÇÖs what I like about it.ÔÇØ But Lindelof isnÔÇÖt ready to settle. ÔÇ£My concern about using the Billie Holiday again is, ÔÇÿNow you have to use it three times.ÔÇÖÔÇØ

LindelofÔÇÖs ÔÇ£rule of threeÔÇØ is one of several music commandments. Another one is to play a good song through and see what happens. ÔÇ£I donÔÇÖt like making edits in music unless itÔÇÖs absolutely, totally necessary,ÔÇØ he says. ÔÇ£IÔÇÖd rather cut the picture to the music than the music to the picture.ÔÇØ As ÔÇ£BackyardÔÇØ plays through, he lights up when the lyric ÔÇ£through your windowpaneÔÇØ lines up with Nora locking the kitchen window. The song goes in. And yes, heÔÇÖll find a third place for Billie Holiday.

The wedding sequence, 15 minutes long, involves all his editing imperativesÔÇöwhich he summarizes as ÔÇ£tone, transition, music, pace.ÔÇØ For NoraÔÇÖs entrance to the wedding, he hunts through a list of 300 songs compiled by his music supervisor Liza Richardson, and finds Robin TrowerÔÇÖs ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm Out to Get You.ÔÇØ The next wedding song is Otis Redding and Carla ThomasÔÇÖs ÔÇ£New YearÔÇÖs Resolution.ÔÇØ Redding is a particular favorite of both Lindelof and Kevin Garvey. They thought about him for the opening theme in season twoÔÇöbut Otis is expensive. ItÔÇÖs easy to get attached to songs that wonÔÇÖt clear. ÔÇ£You get tempitis,ÔÇØ says Lindelof. He wants to try a second Redding song, ÔÇ£IÔÇÖve Got Dreams to Remember,ÔÇØ over Kevin and NoraÔÇÖs emotional dance, Back in Clunes they shot it to Bob SegerÔÇÖs ÔÇ£WeÔÇÖve Got Tonight,ÔÇØ but tempitis couldnÔÇÖt overcome the fact that Mr. RobotÔÇÖs finale used ÔÇ£TonightÔÇØ five days after the Clunes shoot. The opening line of the Redding song, ÔÇ£IÔÇÖve got dreams,ÔÇØ plays on NoraÔÇÖs face as Kevin gives her his hand. ÔÇ£Oh, Jesus,ÔÇØ says Lindelof, shivering slightly, before letting it play through. ÔÇ£Okay thatÔÇÖll work! ThatÔÇÖs amazing. Oomph.ÔÇØ He cuts their dance to OtisÔÇÖs bridge, so that the lyrics ÔÇ£bad dreamsÔÇØ play on KevinÔÇÖs face, ÔÇ£sweet dreamsÔÇØ on NoraÔÇÖs, and so on, as the couple slow-dances.

A couple of seconds of LederÔÇÖs experiment with the empty dance floor make it in, but only because they were the best takes. Lindelof does keep the crane shot Leder joked about him hating; he actually loves the way Kevin recedes as Nora walks. ÔÇ£HeÔÇÖs like, ÔÇÿI just did my John Cusack moment and fucking put my boom box over my head and it didnÔÇÖt work.ÔÇÖ So heÔÇÖs at a loss. ThatÔÇÖs what that shot is telling us.ÔÇØ

During the slow dance, we could hear through the back wall the shoot-ÔÇÖem-up action of episode seven. In neighboring offices, editors are working on episodes further along in the production cycle, with Lindelof occasionally popping in. Visual effects are being tweaked for episode five; Lindelof has a fake-looking light taken out of the nuclear submarine. Effects on the show almost always aim to enhance what was already thereÔÇörain or sun or existing animals. Rupert was too still during a sequence when heÔÇÖs supposed to be fighting to free himself from a fence; his angry bleats and head jerks will be done in post. There are tricks on The Leftovers, but they mimic reality.

FIVE THINGS LINDELOF TWEAKED IN THE EDITING ROOM

Two days later, after I left, Lindelof tackled ÔÇ£Nora makes tea.ÔÇØ At first viewing, he had found LederÔÇÖs cut very ÔÇ£pausy,ÔÇØ with lines that felt overwritten. He wanted to trim the whole thing by a minute or two. But once he dug in, it became slightly longer, without a single line changed or cut. Instead, he attacked issue No. 1: what the audience thinks is going on. Nora, in his opinion, was getting too emotional too fast, and too many close-ups on her face against the white sky, while beautiful and suggestive, put distance between her and Kevin (and felt a little 2001 to boot).

In LederÔÇÖs cut, Nora starts tearing up even before she starts talking about her children. In LindelofÔÇÖs, she becomes visibly emotional only when talking about her relationship with Kevin, and much of her speech is seen over KevinÔÇÖs shoulder, tethering the couple. Lindelof also delayed the start of composer Max RichterÔÇÖs score, one of a handful of themes that define The Leftovers, until almost the very end. He added another half-second flashback, this time to NoraÔÇÖs last LADR moment.

Even though HBO had made the rare gesture of promising no notes on the finale, there were still weeks of postproductionÔÇösmall-group screenings to tweak light and sound, add effects. One of those is a ÔÇ£music spotÔÇØ a week after Lindelof finishes his edit. Richter Skypes into a meeting in Van EeghenÔÇÖs office; on the couch are Lindelof, Spezialy, Richardson, and music editor Amber Funk. Most of the crew are seeing the finale for the first time. After it ends, there is a moment of reverent silence before Lindelof begins explaining whatÔÇÖs foremost on his mind, NoraÔÇÖs tale. ÔÇ£SheÔÇÖs obviously getting affected by her story, but itÔÇÖs very controlled,ÔÇØ he says. ÔÇ£From my Judaic perspective, itÔÇÖs a very Waspy iteration of the scene. WeÔÇÖre not playing to the rafters, but I feel like you really lean in and hang on to every word.ÔÇØ

Does the dryness (musical and emotional) make NoraÔÇÖs story more or less believable? Lindelof doesnÔÇÖt ask the question that way. He simply waits until Richter finishes praising the finale and asks, ÔÇ£Do you believe her?ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£I completely believe her,ÔÇØ Richter says. ÔÇ£Goddamn it!ÔÇØ says Lindelof, half-joking. ÔÇ£Any moisture in the eyes whatsoever?ÔÇØ ÔÇ£A good amount of moisture,ÔÇØ Richter reports. ÔÇ£It must be the connection,ÔÇØ Lindelof says. ÔÇ£It got lost in the darkness of your turtleneck.ÔÇØ

Richardson tells Lindelof that two of the temped songs will have to go, including the first Otis number. SheÔÇÖll find replacements, but the good news is they can keep his favorites, ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm Out to Get YouÔÇØ and ÔÇ£IÔÇÖve Got Dreams to Remember.ÔÇØ ÔÇ£Thank God,ÔÇØ says Lindelof. He threatened to bankroll the second one himself if he had to.

The prospect of losing songs feels jarring even to me, who has zero creative investment. Tempitis is contagious. Watching clever jokes lopped off or gorgeous shots casually discarded or even the showrunnerÔÇÖs pet songs killedÔÇöand this on a show lucky enough to make it to three seasons on low ratingsÔÇöis a painful experience. ItÔÇÖs hard to watch people lose control over their favorite things, to see great ideas die unseen. But ultimately control is an illusion, because thereÔÇÖs only one person who decides what a show really means, and thatÔÇÖs the viewer.

ÔÇ£What do you think of the episode,ÔÇØ Lindelof asks Richardson. ÔÇ£Do you believe her?ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£Yeah,ÔÇØ she says.

ÔÇ£You do?ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£ShouldnÔÇÖt I? Obviously in real life I donÔÇÖt believe it, but I believed her.ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£Okay, okay,ÔÇØ says Lindelof.

ÔÇ£WhatÔÇÖs the answer?ÔÇØ she asks.

ÔÇ£There is no answer. IÔÇÖm just curious.ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£I feel very resolved. IÔÇÖm glad you didnÔÇÖt leave me hanging.ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£And now you know where everybody went,ÔÇØ says Lindelof.

It was an irony as satisfying as anything in the show: Lindelof had summoned up the courage to set aside the burden of Lost and craft yet another deliberately ambiguous series finaleÔÇöonly to discover that almost no one thought it was ambiguous at all. And that, he tells me, is fine with him. Or anyway, it has to be. ÔÇ£My own precious artistic intentions aside, whether Nora is telling the truth may not be up to me anymore,ÔÇØ he says. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs interesting to imagine that whoeverÔÇÖs watching this in June is just going to take it at face value, and IÔÇÖll have to live with that for the rest of my life.ÔÇØ

Design and Development: Jay Guillermo, Terri Neal, Ashley Wu and Jeni Zhen