“I’m feeling a little murder-y,” says Marti Noxon, which sounds not unlike something you’d hear from the mouth of Buffy Summers, the iconic cheerleader turned Hellmouth avenger. This is not surprising, given Noxon began her writing career on Buffy the Vampire Slayer back in 1997. Come to think of it, when I meet her for breakfast at a hotel in Tribeca, she looks much as I imagine Buffy might, if the character had made it to the age of 52.

Though I’d arrived well before our scheduled meeting, I find Noxon — who’d flown in from L.A. late on the previous night — already ensconced in the restaurant, her murder-y feelings prompted by her lodging in a claustrophobic room facing a wall. “It’s kind of like being jailed,” she says, “but a really nice jail, like for a white-collar crime.” Three or four times this morning, she reports, she’d considered asking for a better room — but she didn’t, because she assumed they would say no. And “that will be sadder because they probably do have one,” she jokes. “They just somehow know that I’ll settle for less.”

If the hoteliers were acquainted with her current workload, they’d likely not suspect her of settling. Her first film, To the Bone, which she wrote and directed, about a woman battling anorexia, will begin streaming on Netflix on July 14. Simultaneously, she’s been developing the first show in a seven-figure, three-year deal she signed in 2016 with Skydance Media: AMC’s Dietland, based on Sarai Walker’s best-selling novel. She’s also been finishing up the last season of Bravo’s Girlfriends’ Guide to Divorce, and filming’s begun on her HBO series Sharp Objects, which she’s adapting from Gone Girl author Gillian Flynn’s debut novel. “It feels like in the last five or six years, I’ve been hitting my stride” is the closest Noxon gets to patting herself on the back. She has the Waspish tendency to downplay — well, everything. She’s also seductive: a disarmingly candid, fun, and openhearted insta-friend. But not without the inherent boundaries of a woman who has sustained, as she puts it, “damage.”

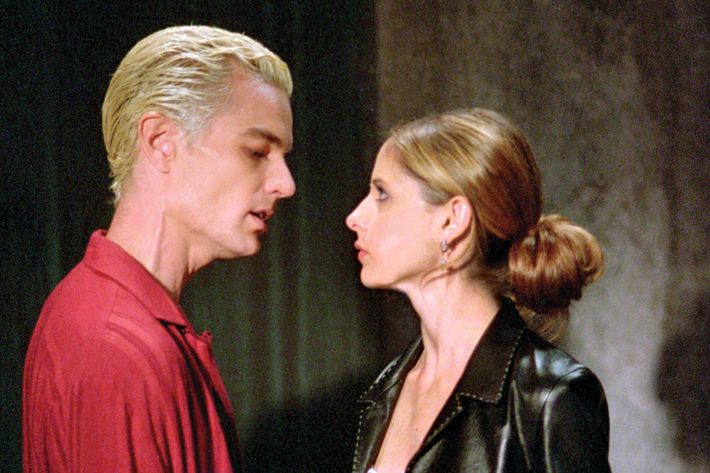

In some ways, Noxon’s first writing job was a tease. Buffy, as run by Joss Whedon, offered Noxon not only an extraordinary creative playpen but also a rare safe place to flourish in a still-male-dominated TV universe. “The reason I fell in love with Buffy was because of the ambiguity, because she was a superhero and a hot mess. I hadn’t seen anything like her on TV — ever,” says Noxon. “At the same time, for me, there was always the big debate: Dating vampires is a bad idea. So let’s have some consequences for these choices! It’s the only way you learn.”

Promoted to executive producer in 2001, she helmed the show’s controversial sixth season, during which, among other things, Buffy falls into a deep depression and starts acting out after her friends resurrect her from death. (It turns out she had been in Heaven, not Hell — whoops.) Noxon took serious heat from fans — and this was well before social media. “For some people, including [star] Sarah Michelle Gellar, it felt like a betrayal of where we had started,” says Noxon. “We had said this show is going to be weird, but I don’t think we’d said that it’s going to be really fucked up.”

Noxon has a fondness for awkwardness, and a successful character, to her mind, doesn’t need to be liked — an attitude uncommon in 2001, particularly when it came to women. “The bane of every TV writer’s existence is the likability note,” she says — though a lot of grief was coming from the show’s female fans, unused to seeing a heroine break bad. I suggest to her that in a TV universe that now includes the angry, damaged women of UnREAL (which Noxon co-created with Sarah Gertrude Shapiro), Fleabag, and I Love Dick, the reaction to season six of Buffy would be entirely different. Noxon agrees, then adds that, furthermore, “every project that I currently have is about women who are deeply, deeply messed up.”

Noxon’s Twitter bio makes comic hay of the backlash — “I ruined Buffy and I will RUIN YOU TOO” — but it wasn’t fun to go through. “I hadn’t gelled yet as a writer, or found a voice that was unique to me,” she says. “And I was really afraid that I didn’t have the right stuff. I think a lot of my subsequent choices were dictated by that fear.” After Buffy, she found herself drifting into mediocre shows, and one, 2005’s Point Pleasant, seemed to confirm her insecurities. “A critic gave it a negative review, and literally name-checked me, because he’d liked my work on Buffy,” she says. “I was like, Oh, wow, that hurt. It got me to a really good shrink.”

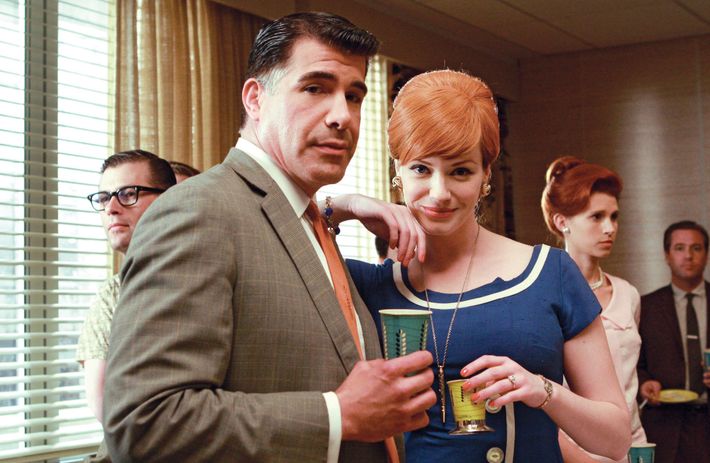

In 2008, she landed at Mad Men, during its second season, and as part of that writing team won two WGA Awards. I point out to her — in reference to creator Matthew Weiner’s legendary control-freakishness — that at least she got to write. “Kind of,” says Noxon, with a laugh. “That was such an interesting experience. On the one hand, it was like boot camp, going back to the basics of good writing — ambiguity, mystery, scenes that are about taking a breath, not just propelling things forward. So many good things that I needed to relearn. On the other hand, Matt wasn’t happy, hardly ever, about anything the writers did. The message from him was, ‘Only I can do this.’ ”

So — the exact opposite of Whedon? “Joss’s genius was oppressive in a different way,” she says. “He’d come back from a weekend having written a musical, never having written music in his life. And you’d be, Fuck me. I’m not even going to try.” At the same time, “every once in a while someone will say to me, ‘How do you do all this?’ And I think, Oh, I’m somebody’s Joss now! I went and directed a movie while working on multiple TV shows! Somebody out there probably thinks, Fuck her. And I think: I’ve arrived!”

Noxon is in New York to be honored by Project Heal, an organization that provides grants to subsidize treatments for people with eating disorders. Her film, To the Bone, not so loosely based on Noxon’s own story, is about a 20-year-old woman, played by Lily Collins, with life-threatening anorexia. As a high-school senior, Noxon weighed 69 pounds — this after years of ineffectual medical treatment. She finally got better thanks to a doctor’s then-radical therapy, one that stresses emotion rather than weight. (Keanu Reeves plays the doctor based on Dr. Richard MacKenzie, who still practices at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.)

Noxon found her voice (or, if you want to get Buffy about it, her superpowers) by finally writing about deeply personal subjects. As she began turning her anorexia into a film, she discovered something curious: There were no prominent feature films about the subject, only TV movies. It quickly became clear why: Male studio executives considered the subject of anorexia “a disease movie that nobody wanted to see,” she says. “I had one producer tell me, ‘It’s such a small topic.’ A small topic? Throw a rock in your office and you’ll hit a woman who is harming herself one way or another.” It took three female producers to get To the Bone made; Netflix picked it up after its premiere at the Sundance Film Festival in January.

“A funny sidebar,” she tells me of her own story, “is that when I was stuck between high school and college — because I was too sick to go — my stepmother heard that Jennifer Jason Leigh was doing a TV movie about anorexia and needed a body double.” Noxon was hired, but a writers’ strike put a halt to production — abruptly ending her career as “a professional anorexic.”

A particularly striking scene in To the Bone must have seemed ridiculous on paper: Ellen’s mother, played by Lili Taylor, pulls her grown daughter onto her lap and nurses her with a bottle. “Most people involved with the film were very nervous about that scene,” Noxon admits. And yet, as it plays out, it becomes one of the film’s most moving. “It really happened,” she says, “and it was as wildly awkward and uncomfortable as it looks in the film.” When I ask why she agreed to this extremely flaky therapy, Noxon says, “I think I felt like it would be rude to tell my mother that I didn’t want to do it.”

Noxon grew up in L.A., and after her parents split, when she was 8, she and her younger brother, Christopher (who’s now married to Jenji Kohan, creator of Orange Is the New Black), moved between their parents’ households. Her father, a documentary filmmaker for National Geographic, remarried a woman with three children; her mother — married twice more, once to a woman — behaved erratically until finally being diagnosed with bipolar well into her 50s. “One of the ways that manifested when we were growing up was that all of a sudden the rules would change, sometimes overnight,” says Noxon. “ ‘Now I’m a Buddhist’; ‘Now I’m an alcoholic’; ‘Now I’m a sober alcoholic’; ‘Now I’m not an alcoholic’; ‘Now I’m a lesbian.’ ” With proper medication, “she’s still a Buddhist and a lesbian, so some of that stuck. It was interesting to finally meet her: ‘Oh, that’s who you are.’ ”

Some therapists now consider advanced anorexia to be a psychotic disorder, which confirmed Noxon’s suspicion that anorexics “don’t want to be in this world. That was my feeling, too. For me, the interesting thing about anorexia is that you show your wound. There’s no hiding it. So my anger and sense of disappointment, all the stuff I was out of touch with, became this visible rebuke to my parents. Just to look at me was a Fuck you.”

She envies friends who grew up in families with a better handle on self-expression and anger, like her sister-in-law. “Jenji and her mom just scream at each other, and somehow the world doesn’t implode.”

After Noxon started to put weight on, the underlying problems remained. “In college I began to function and learn and enrich myself, but I still had this whole secret life,” she says. “My last year, I tried alcohol. For me it was like” — Noxon claps her hands — “Why in the world would you starve yourself when you can do this instead? Anorexia is not fun at parties.”

Drinking became the new crutch. She finally got sober and stayed sober for 24 years, before relapsing six years ago during her divorce from Jeff Bynum, a fellow Buffy writer. (They have children, a 14-year-old daughter, Laney, and a 12-year-old son, Jed, which explains the J & L tattooed on the inside of her left wrist.) Hitting menopause didn’t help. “There are no good role models for that,” she says. “We still operate with this old, three-stage model of rise, plateau, and then, when you hit 50, decline. ‘Happy birthday, it’s all downhill from here!’ ” She wrote menopause plots into Girlfriends’ Guide to Divorce, only to get reprimanding notes from the network: “It’s not sexy, it’s not Bravo.”

If Noxon has found her sweet spot creatively, it’s a relentlessly dark one. Each of her current projects features a woman in crisis: There’s Ellen, of course, slowly starving herself to death; Sharp Objects’ Camille Preaker has been hospitalized for cutting; and Dietland’s 300-pound Plum Kettle has tried life-threatening methods of losing weight. After considering this, Noxon exclaims: “It’s the self-harm trilogy!”

She read Sharp Objects after her divorce, in the midst of trying to get sober the second time. “At first, I didn’t even relate it to the fact that the character was doing self-harm, and that it was part of my own story,” says Noxon. “I just was aware, when I put the book down, that I’d never felt as inside a female character.” It got her thinking about how we don’t talk about the violent impulses of women, “except as it relates to harm that’s come to them at the hands of men,” she says. “We don’t talk about having our own instincts to do bad things to ourselves and each other, and not just because bad has been done to us. There’s something weirdly feminist about taking men out of the story.”

Noxon “couldn’t stop poking at” the story and eventually sold her pitch to HBO. Amy Adams is starring as Camille, the journalist who goes back to her hometown to investigate the murder of two preteen girls. Noxon invited Gillian Flynn to join the writers’ room, and there was instant rapport. “The first time I met Gillian,” she says, “I asked, ‘What’s your damage?’ — because mine is pretty easy to pinpoint. But she was, like, ‘I don’t know, I just love this stuff.’ We make a funny pair because we look like we could be on the same cheerleading team, and yet we’re both dark-hearted bitches.”

A week after I met Noxon in New York, I visit the Dietland writers’ room. Dietland’s plot involves a terrorist group called Jennifer that kidnaps and kills known rapists and misogynists in sadistically imaginative ways, like dropping them out of planes. “One of the sly things about the book is that it has the conventions of a romantic comedy, it feels a bit like chick lit. At the same time, there’s a Fight Club quality to it,” says Noxon. “But it also digs deep into reality. It connected me to a level of anger I didn’t even know that I had.”

One of the book’s philosophical questions, which Noxon became eager to explore, was whether it’s possible to have a revolution without violence. “Like a lot of women, I’ve been raped, and I’ve had physical intimidation rule a lot of my thinking — subconsciously most of the time. There’s continuous genocide perpetrated against women throughout the world,” she says. “I don’t advocate violence, but I did have this moment while reading the book: Why haven’t we taken up arms?”

Tiny Pyro, Noxon’s female-run production company, is temporarily occupying the third floor of the Los Angeles Athletic Club in Hollywood, where she and her writers are wrapping up the scripts for the first five episodes. AMC’s new development model is a straight-to-series track, which opens up a writers’ room for a production under consideration (rather than financing just the pilot). Noxon considers this model a smart one since AMC will get to see more of a show before committing to production; however, “it’s a little more brutal because you get way more invested.”

Her writers — six women, including Dietland author Walker, and two men — gather around a table. Around them are whiteboards with episode breakdowns; on one, at the top, The PENIS 100 is written, a reference to the book’s “Penis Blacklist”: the names of men, released by Jennifer, who “must not be given shelter inside any woman.” (Women who fraternize with Jennifer’s targets are at risk of death as well — did I mention this book is dark?) “Sometimes when I’m reading a script,” Noxon will say later, “I can’t quite believe that this is going on television, alongside cereal commercials.”

Food is plentiful, and everyone is dressed as you might for a long plane flight — the outdoor equivalent of pajamas. The days this week will be long. The first hour is a warm-up — lunch is eaten, the news is dissected, cupcakes are ogled. The workday is devoted to addressing comments from the network. The vibe in the room is sisterly and chatty, and Noxon’s big laugh repeatedly rings out. One of the writers later equates the experience to group therapy. “The room has been one big hug,” she says.

Noxon had told me in New York that increasingly she chooses her writers very carefully, to establish that everyone will feel safe to speak out and that she will have that freedom, too. “In the kind of shows that I do, you need to talk about everything,” she says. You need to bring what she calls “your ugly stuff.” A male writer who worked with Noxon after years in rooms run by men tells me that her approach — enthusiastic and collaborative — does make people feel safe, both to be candid and to make mistakes; and there is none of the old-school macho stuff, the passive-aggressive competitiveness. “You never doubt that she’s in charge without her having to keep telling you she’s in charge,” he says. “She doesn’t come in with a lot of rules — always a sign of insecurity. And she doesn’t come in knowing exactly what story she wants. But she does come in knowing what show she wants to make.”

Given all the depressing stories about the lack of women and minorities working in film, Noxon has encouraging news about television. “The mandate for change within the industry has been serious,” she says. “In ten years TV will look very different, particularly now that there are so many women executives who are deciders.” She has had more than a few writers attempting to break into the business complain to her about losing jobs because they are white men. “At one point,” she says, “the female writers on Dietland joked to the two males, ‘You’re our token dudes.’ And I’m thinking, Is that going to be a problem soon?”

Speaking of dudes: Joss Whedon was 32 when he created Buffy, but Noxon has only just hit her stride, as she put it. Does she think it has something to do with the sense of entitlement bestowed upon boys when they’re growing up? She doesn’t feel a comparison with Whedon is quite right; “I needed to go through what I did to get where I am,” Noxon says, but she does offer a telling anecdote: “I was meeting with a studio about directing a superhero movie with lots of big FX,” she says. “I was worried about not having had time to prepare. And this woman I know said, ‘In my opinion, men come in with 60 percent and brag on it, and women come in with 90 percent and they apologize for the 10 percent they don’t have.” Her friend advised Noxon to never apologize, to just come in and say she didn’t have time to fully prepare. “And part of my brain went [Noxon makes a mind-blown sound], Is that how it works? You brag the 60 percent?”

This reminds me of Jill Soloway’s topple-the-patriarchy speech at last year’s Emmy Awards. “I definitely see a new wave of empowered women right now,” Noxon says approvingly, and she is ready to embrace it. “It’s partly getting older, but for the first time in my life I feel just enough franchise, just enough room in the world, to say, ‘Take me as I am, or don’t take me.’ ”