Netflix’s new true-crime series The Keepers tells a familiar story. As its very thorough trailer makes clear, it’s a series about a murder, with the added fillip of sexual abuse in the Catholic Church — a tale so common that it’s now been told through investigative journalism, an Oscar-winning film, and multiple Law & Order episodes.

And yet, at its core, The Keepers is built on a different scale than many of the other series in its true-crime cohort. Where shows like The Jinx or Making a Murderer focus intensely on a small handful of individuals, and tend to center their storytelling on a few obsessively detailed criminal investigations, The Keepers casts an unusually wide net. From the initial focus on the death of one nun, Sister Cathy Cesnik, it then spins outward to encompass a story full of horrific sexual abuse, apparent cover-ups, and a massive web of tenuous, suggestive, notable, and often unproven connections.

If you’re looking for analogous models in fictional series, The Keepers is not Top of the Lake or The Honorable Woman or True Detective. Many fictional crime series reach for broad networks of conspiracy, but they almost always boil down to a few primary players: the detective. The murderer. The red herring. The key witness. The Keepers doesn’t work that way; it is not Sherlock Holmes. It’s The Wire.

True-crime series often feel like a game of cat and mouse. In the story of the crime, the mouse is the victim, captured by the cat and probably murdered in some unusually horrible and puzzling way. Once that story becomes a crime series, that relationship is inverted. The alleged killer becomes the mouse, relentlessly pursued by the catlike instincts of the investigators. And in some true-crime narratives, including many of the recently popular TV and podcast true crimes, that sense of pursuit from the investigators is especially intense because they’re also the filmmakers or narrators. It’s not just that investigators chase the murderer to bring him (it’s generally a him) to justice — it’s that the entire narrative is built from the perspective of the detective, with no space at all between the investigation and the narratorial eye.

That closeness between the eye of the investigator and the eye of the storyteller leads to intensely emotional, watchable TV, and compelling podcasts. The Jinx is a series about murder and privilege and sociopathy, but it’s also about the unbelievably bizarre relationship between Robert Durst and filmmaker Andrew Jarecki, who circle each other in a series of one-on-one interviews that come off like a cross between an interrogation and a nightmarish first date. The same is true for two iterations of the This American Life–related true-crime narratives, S-Town and the first season of Serial. Both of those stories are supposedly about a crime (or some probably imagined crime, in the case of S-Town), but become mostly about the fraught, troubling, multifaceted relationships between the narrators and the series’ subjects. Even Making a Murderer, where the filmmakers never appear directly, is clearly shaped by the organizing eye of its filmmakers, which, as critics have noted, seems less interested in searching for the truth than in arguing for a predetermined position.

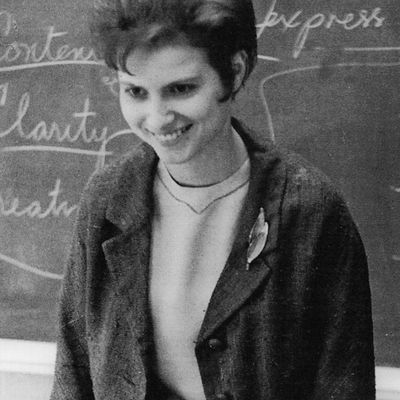

The Keepers is different. For one, it is far more female. Anne Helen Petersen writes that the women of The Keepers deploy tools “often delegitimized or degraded as feminine” to pursue their goals, and that this is one of the most vital aspects of what has kept this story alive. They are “women who believe women.” It’s absolutely true, but the importance of that statement is not just about the femininity of the players. It’s also about the plurality.

In telling the story of Sister Cathy Cesnik, and in presenting all the evidence it can relating to her death, The Keepers becomes a suggestive, fascinating tangle. The story is not just about one criminal, but possibly several. Not one victim, but dozens. Not one detective, but many – several journalists, two amazing, dogged amateur investigators, and the filmmakers themselves, as well as many other curious, interested parties. With each new line of inquiry the scope of the story expands, encompassing new characters and new pieces of evidence. The series gradually swells across time as well, and ultimately becomes so broad that viewers eventually realize several of the major players have never even met one another.

When I say that the series is like The Wire, this is a large part of what I mean: The shape of events at Archbishop Keough High School becomes clear through a multiplying, crisscrossing network of individuals with their own personal narratives, telling different pieces of the story from different vantages and wildly diverging interests. In one scene we watch Gemma Hoskins and Abbie Schaub talking about how important it is to find justice for their beloved high-school teacher. In another, we see Jean Wehner struggling to recount her memories of abuse by the school’s chaplain. In yet another, the filmmakers interview Sharon May, who blankly explains why she never brought charges against the school during her time in the district attorney’s office. The total view of what may have happened at Archbishop Keough High School in 1969 only becomes clear from a distance, as an interlocking network of many, many stories.

Some of those stories directly contradict one another. Some of them fall into eerie parallel. Many of them remain stubbornly, elliptically unresolved by the end of the series, and in this respect, The Keepers is even more like The Wire than its massive cast of characters first suggests. Mystery narratives often feel like a slow winnowing, with a few clues and a few characters who return again and again until their roles finally become clear. They are often built on paucity. The Keepers, conversely, is built on surfeit, the kind of frustrating, overwhelming burden of evidence that eventually becomes a landslide of clues. Except, as one of the series’ frustrated amateur investigators notes, they are wires that never quite seem to connect. As Alex Abad-Santos writes for Vox, “feeling satisfied” isn’t really “the crux” of the show.

In lieu of a satisfying ending, or even some kind of symbolic closure for the abuse victims, The Keepers sketches a vast image of something far more frustrating. It’s a depiction of institutional failure on the level of the school, the archdiocese, the police, the FBI, and the district attorney’s office, not just once, but repeatedly since Sister Cathy’s death in 1969. It’s a story that avoids too-easy closure in favor of a broader account of influence, privilege, oppression, and the unending, often futile struggle that individuals constantly wage against immense institutional machinery.

From that perspective, The Keepers’ Baltimore looks like it could easily be another piece of David Simon’s Baltimore, although its victims and detectives are both whiter and significantly more female. But it’s worth noting, amid all of the horror and failure and absent justice, that The Keepers also reflects something of The Wire’s small core of hopefulness. Even in the face of persistent bureaucratic suppression, the individuals — the women — of The Keepers soldier on gamely, frustrated but not deterred. The series does not have the game of cat and mouse that’s so notable from The Jinx or Serial, nor is it intensely focused on a small handful of players. It’s a more communal story, which means it’s a deeply upsetting account of crimes committed on a massive scale. But it’s also the story of many, many people trying very hard to find justice.