As 1986 dawned, the most famous woman in superhero fiction was in trouble, and not the fun kind. Wonder Woman faced a deadlier villain than any preening megalomaniac or gimmicky sadist: irrelevance. “For almost four decades, there really had been almost no memorable Wonder Woman stories,” recalls Paul Levitz, comics historian and longtime executive at the character’s publisher, DC Comics. “Stories were just sorta there for the month. It was unusual for one of the legendary characters of the comics field to have that long a dry spell.”

Then, along came George.

If you stick around for the end of the credits at this weekend’s Wonder Woman, you’ll see a list of comics creators the producers wish to thank for cooking up ideas that influenced the film. One name appears at the top of that list, bigger than all the others and given the pride of an extra line break: George Pérez. If you’ve achieved a certain level of comics geekdom, you’ll know full well why that’s the case. Thirty years ago, Pérez — a writer and artist of astounding talent — became the man who reinvented Wonder Woman and told what is arguably still her greatest story.

His influence resonates loudly at the multiplex. To be fair, Pérez’s name isn’t technically the biggest one for a comics person in the credits — that honor, appropriately, goes to the guy who unveiled the character in 1941, William Moulton Marston. Marston’s story and that of his Wonder Woman tales have been told at length, thanks in large part to the efforts of writer Jill Lepore in her acclaimed 2014 book The Secret History of Wonder Woman. But Pérez’s impact on the picture should not be underestimated. When a fan recently asked Wonder Woman director Patty Jenkins during a Twitter Q&A which comics storyblines most influenced the script, she only cited one creator other than Marston, and it was Pérez:

What made the work of this man, far more unsung in the mainstream than contemporaneous peers like Frank Miller and Alan Moore, so powerful, and in what ways is that power reflected onscreen in Wonder Woman’s solo box-office debut? The answers lie in a tale that hasn’t been told until now, but one well worth exploring if you want to understand not only the film’s roots, but also the history of a pivotal era in American comic books — and, most important, if you want to understand what makes this iconic character tick.

The story begins in a time of crisis. In the early 1980s, DC had struggled with a problem that was alienating readers both old and new: continuity. In superhero comics, stories accumulate over time, meaning Superman will recall fights that readers consumed years prior, and what Batman does in one story might affect Green Lantern in another one. It’s a genius concept for stoking obsession, but it’s also a dangerous one, in that decades of continuity can lead to convoluted and contradictory character histories that are near impossible to follow.

No character suffered from the ailments of continuity more than Wonder Woman. First introduced in 1940s tales that formed a kind of pop-culture feminist urtext, she had been depicted as a lasso-wielding warrior named Diana from an advanced society of ancient Amazons on a place called Paradise Island. She was a liberated woman before people generally spoke of such things, possessing an array of superpowers ranging from super-strength to ESP, as well as a curious fondness for bondage. She comes to the world of men to fight Nazis alongside a military love interest named Steve Trevor and best friend Etta Candy, a mouth-stuffing, plus-size woman who provided comic relief. It was as wonderful as it was eyebrow-raising.

Those early stories were simple enough, but over time, they were revised and rethought over and over to the point of near insanity. Readers learned that the WWII Diana actually lived on an alternate-reality planet called Earth-2, and that there was another Diana that they’d retroactively been reading about for the past few years. They perused multiple retellings of her origin story that rewrote not only her narrative but the nature of her powers, and that couldn’t be easily reconciled with one another. Then she lost her powers entirely and became a mortal woman who trained under a racist caricature named I Ching. Then she became an Emma Peel–esque super-spy for a while. It was enough to make your tiara spin.

As 1985 dawned, Wonder Woman was decrepit in a way that her main peers, Superman and Batman, weren’t. As a result, she was something of a redheaded stepchild within DC, rarely met with enthusiasm by those assigned to her. “The character was an important part of DC history and legacy,” recalls Wonder Woman editor Karen Berger, “but it wasn’t the one that writers and artists flocked towards.” Lucky for Wonder Woman, DC was looking to wipe the slate clean across their entire publishing line. Enter 1985-6’s Crisis on Infinite Earths, a mega-event in which the DC multiverse was destroyed and replaced with a fresh, streamlined version. Old versions of characters would die and, phoenix-like, rise again as young figures whose origins made sense and who had been reimagined as Platonic ideals of themselves.

Crisis required an artist (well, technically, a penciler — artwork in comics is typically done by a penciler, an inker, and a colorist, but pencilers are regarded as the leading visual force) who could rise to the task and had a name that would generate enthusiasm from readers. There was an obvious choice: Pérez. A stunning renderer of both minute detail and expansive spectacle, an innovative creator of page layouts and a master of facial “acting,” Pérez was one of the best draughtsmen in the industry, having made a name for himself on a series called The New Teen Titans. Alongside Titans writer Marv Wolfman, Pérez knocked it out of the park on Crisis and was at the top of his game.

That Pérez-drawn mini-series utterly changed the DC pantheon. In its wake came writer-artist John Byrne’s seminal The Man of Steel, a stark new vision of Superman that flew off the shelves. Similarly, new versions of other characters sprung up across the DC lineup. Even beyond the books affected by Crisis, it was a time of reevaluation at DC: Moore and artists Dave Gibbons and John Higgins were publishing the superhero deconstruction Watchmen, and Frank Miller was writing and drawing the now-legendary Batman tale The Dark Knight Returns with artists Klaus Janson and Lynn Varley. Everything was up for grabs, nothing was fixed. So with Supes and Batsy being taken care of in those aforementioned titles, the next step seemed natural, says Levitz: “It couldn’t hurt to relaunch Wonder Woman.”

Initially, editor Janice Race and writer Greg Potter were tasked with brainstorming ideas for this reboot. Potter came up with some interesting notions, such as the idea that the Amazons might actually be reincarnations of dead women throughout history and that the main story could be set in Potter’s native Boston, turning Beantown into Diana’s own Metropolis or Gotham City. But the brew wasn’t quite ready — as Pérez recalls, it wasn’t progressive in the way the Marston tales had been and “female staff were not all that happy with it.” Pérez, hearing that Wonder Woman was getting a new look, thought he might have something to add.

Oddly, Über-geek Pérez had not grown up as a Wonder Woman fan. “Most of the stuff I read, unfortunately, was not the series in her heyday,” he says. A man with feminist leanings, he found a lot of her narratives irritating on gender grounds: “The stories were rather silly. She was basically the male concept of what a female hero was, with the stereotypical trait that they gave to a lot of their female characters, in which she was worried more about having a date than saving the world.”

He only found himself intrigued by her when he started actually working with her in his pre-Crisis days. He did a stint on the series about super-team the Justice League of America, of which she was a member, and grew fond of her. But the tipping point came during a New Teen Titans story that brought the titular titans to Paradise Island. Wolfman’s story had the squad going up against the Titans of Greek mythology. A light bulb went off in Pérez’s head.

Prior to that story, he’d seen creators depict Wonder Woman as a “female Superman,” but all of a sudden, he saw what made her stand apart: She’s not an alien or a god; she’s a myth. “She was more of a fantasy character,” he says. “That was the background of the Wonder Woman character, which I felt was also the thing that made her unique as a character, and I thought that it had been downplayed in order to make her more of a standard superhero.”

So when Pérez got the green-light to co-write (with Potter) and draw Wonder Woman, he set out to go hard on the classical-mythology angle and spent months researching texts on the subject. He decided to rename Paradise Island as Themyscira, the home of the Amazons of classical Greek myth. There would be gods of Olympus meddling in the affairs of mortals. There would be deliberately ornate speeches about virtue and fate. There would be an explanation of why a character from a Hellenistic civilization would have the Roman name “Diana.” There would be no super-spying or cheap romance-novel swooning. This would be a Wonder Woman who deserved the first word in her name.

But the second word would be just as important: This was to be a series that addressed the perils and peculiarities of the ways women are treated in the world. He wanted to talk about domestic violence, about discrimination, about misogynistic ageism, and to not make Diana a sex object. That latter part wasn’t easy, given that he wanted to keep the classic, skimpy Wonder Woman costume mostly intact, but he still made changes at the margins: He got rid of her costume’s high heels, for example. After all, he says, “That didn’t make sense in an island full of Amazons, particularly with no sense of what the fashions were on the outside world.”

Pérez says Berger — the new editor on the project after Race had left it in its prenatal stage — was a huge influence and a vital sounding board, perpetually providing “that extra point of view from a woman’s side of the story.” He says he wanted the character to be an “arch-feminist,” but also a “humanist” — a believer in the fundamental good of all humans, whatever their gender. As Berger recalls, “George strove so hard to really make it a comic that women would wanna read, too, especially young women. That was unusual for a guy who’d been doing superhero comics his whole life. I was impressed by that.”

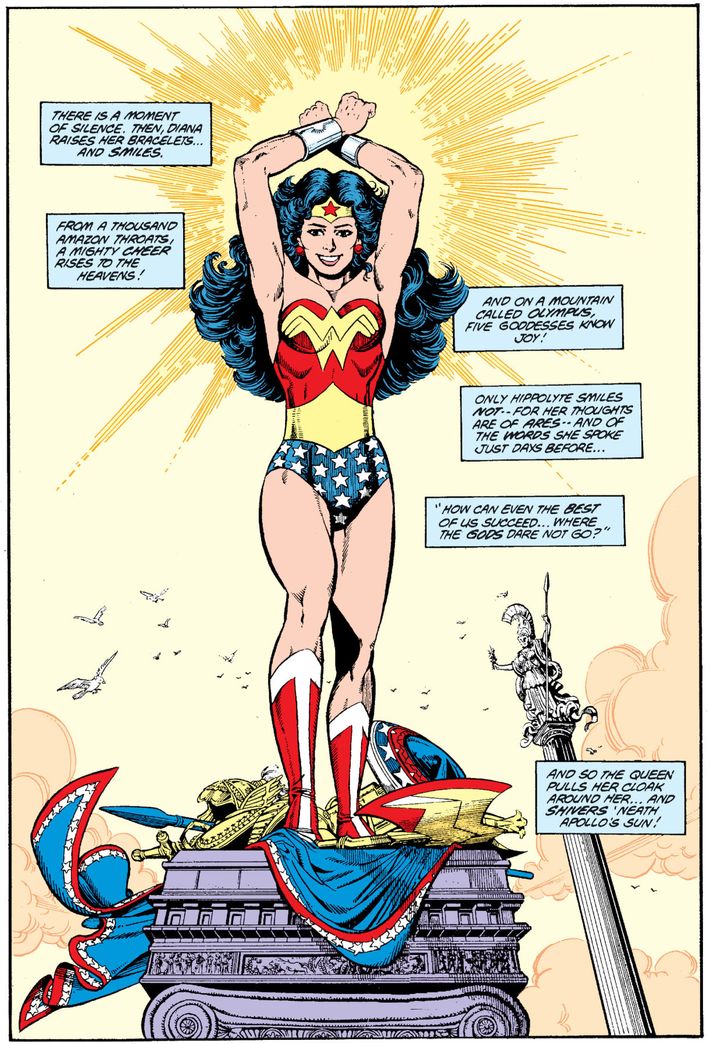

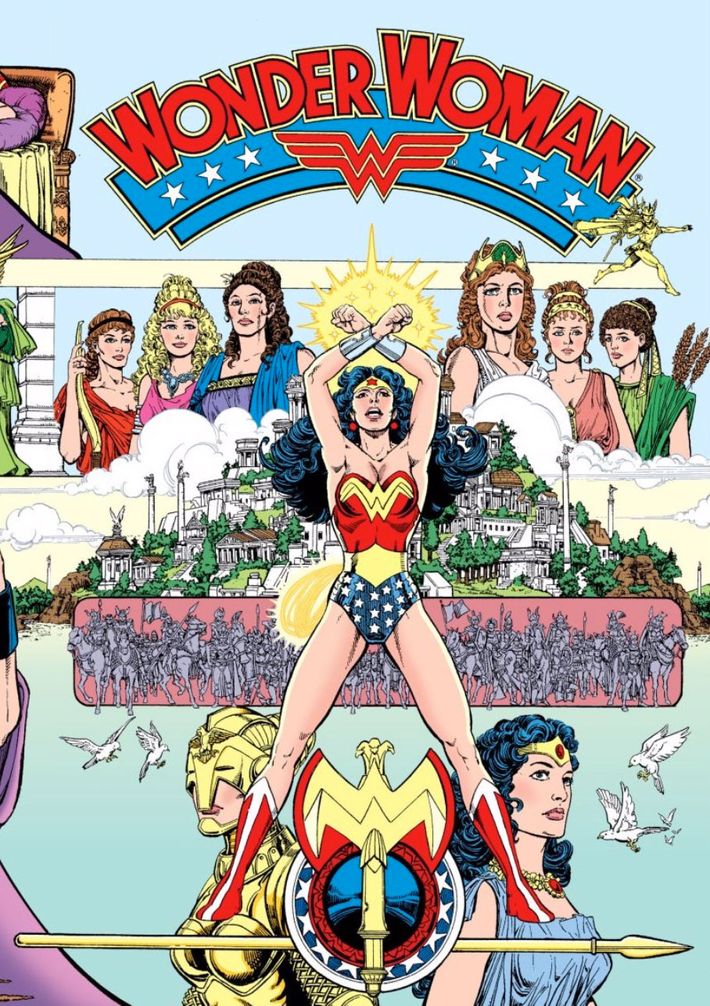

Armed with this philosophy of wonderment and womanhood, Pérez got to work, and DC built up the anticipation throughout 1986. They released a poster with Diana flying across text that declared “FIRST THE DARK KNIGHT. THEN, THE MAN OF STEEL. NOW, DC DOES IT AGAIN. GEORGE PEREZ, GREG POTTER, AND BRUCE PATTERSON” — the inker — “INTRODUCE THE NEW WONDER WOMAN. COMING NOVEMBER 6TH.” When that day rolled around, the first issue hit stands, bearing one of the all-time great comics covers: Diana’s frame taking up much of the page in a modified version of Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, wrists crossed above her voluminous black locks. A pantheon of female gods looms in the clouds around her head, Themyscira thrums below, women warriors on horseback stand at the ready below that, and two women — one Diana’s mother, the other a masked mystery — stand in profile next to a massive spear and shield. It was grandeur incarnate, like a funnybook version of an ancient mural.

The story inside was just as overwhelming, and retains its power to this day. Indeed, it kicked off a 14-issue arc that remains the best possible introduction to the character for the uninitiated. What The Dark Knight is to the Caped Crusader and Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely’s All-Star Superman is to the Man of Steel, Pérez’s first pair of interlinked story arcs is to the third member of the DC Comics trinity: a self-contained story with a beginning, middle, and end that nonetheless leaves you with a hunger for more tales about the axiomatic figure you just read about.

From the very first page, the story declares itself unafraid to be bold and idiosyncratic. It begins with an obscure quotation from French historian Ferdinand Lot: “The gods are dead, killed by the one god. Between the men of the new and those of ancient times there will no longer be a thought in common.” There is no specific meaning ascribed, but it suggests that the story we’re about to read will defy Lot’s assertion and show what it looks like when the gods are proven to be real and their emissary arrives among these “men of the new.”

However, we don’t get that right away, nor do we even get the present tense. The first scene takes place in 30,000 B.C. and centers around a primordial case of domestic violence. A caveman, humiliated that he lost a fight with a sabertooth tiger, returns to his cave and takes out his anger on his mate, killing her — then sees some kind of energy shoot out of her into the heavens. It’s a surreal beginning, one wholly free of superheroes or any kind of traditional superhero iconography. Female Superman, this story ain’t.

We soon learn that the energy was the woman’s soul, traveling to the underworld, where it lies in a kind of storage until a group of female Greek deities concoct a plot to improve humans. That plan involves taking all of these female souls who saw their “lives cut short by man’s fear and ignorance” and rebirthing them in physical form as a new race of noble women who will inspire humanity by their good example: the Amazons. Of course, not everyone on Olympus (stunningly rendered by Pérez as a kind of gravity-defying, perspective-screwing M.C. Escher wonderland) is onboard with this plan, and the god of war, Ares, declares that he will fix humanity through terror and battle. This conflict, between fear and inspiration, forms the core of the subsequent saga.

And what a saga it is. We learn of the Amazons’ ostracization by xenophobic humans; we see their battle with the arch-misogynist Heracles, during which they to go war and feel great shame at having resorted to violence; we see the Amazon queen, Hippolyte, long for a child and get one by molding it out of clay that’s blessed by the gods; we see the child receive the name Diana for mysterious reasons; we see Diana tested in combat against a gun that the Amazons possess for similarly mysterious reasons; and we see the fateful day when Steve Trevor crash-lands on Themyscira, giving the women their first glimpse of a man since Heracles. Wisely, Pérez chose to make Steve middle-aged, in order to prevent him from being a love interest that brings Diana into a cheap love story.

Instead, he brings her the prospect of entering man’s world — or, as Pérez renamed it, Patriarch’s World. She is granted permission to travel to our civilization after the goddess Athena appears to the Amazons and says Diana has a special destiny away from the island. The god Hermes guides her and Steve to Massachusetts as the next step in her path toward destiny. I won’t spoil how the story plays out, but suffice it to say that, although it’s definitely a story about superpowered derring-do, it feels like no other super-tale ever told. Potter left the book after a couple of issues and was replaced by co-writer Len Wein, but Pérez remained the driving force, and his array of story beats were groundbreaking and fascinating.

A working, middle-aged mother, the academic Julia Kapatelis, becomes Diana’s best friend, and the comic explicitly talks about the obstacles faced by older women. Another new friend, a revamped and toned-down Etta Candy, struggles believably and un-sappily with body-image issues. When Wonder Woman makes her debut on the world stage, she is openly religious, drawing scorn from Christian fundamentalists and atheists, alike. The name “Diana,” the fact that her costume has elements of the American flag, and the existence of the gun on Themyscira are all explained with a cracking good twist. It’s a swirl of thrills and surprises.

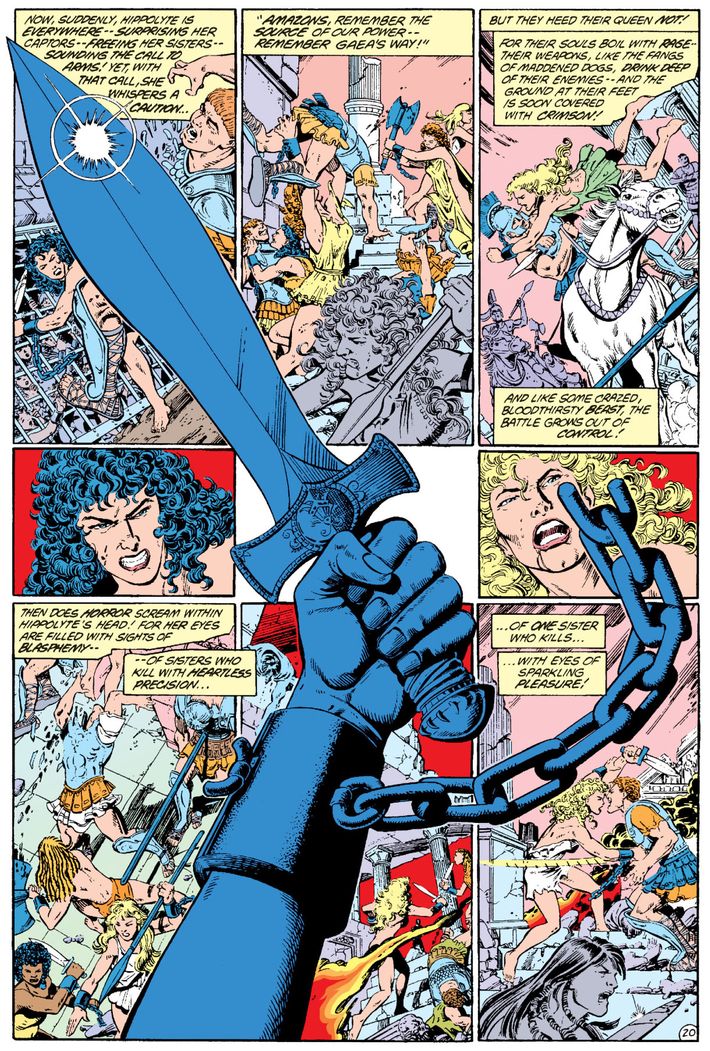

And it’s gorgeous. Pérez is a master of the comics medium, using it to tell stories in ways that film and prose never could. Sure, he’s grippingly good at capturing nuanced facial expressions and action poses, and he can illustrate minute details of background and foreground like no one else, but his most remarkable strength comes in his layouts. Pérez will do things like show a series of conventional panels depicting fiery battle but overlay onto them a massive, page-sized fist clenching a glimmering blade and bearing a bracelet with a shattered chain, thus forcing your eye to move not just left-to-right, but center-to-periphery and, as the narrative loops around the fist and accoutrements, trace your gaze over different details of the central image.

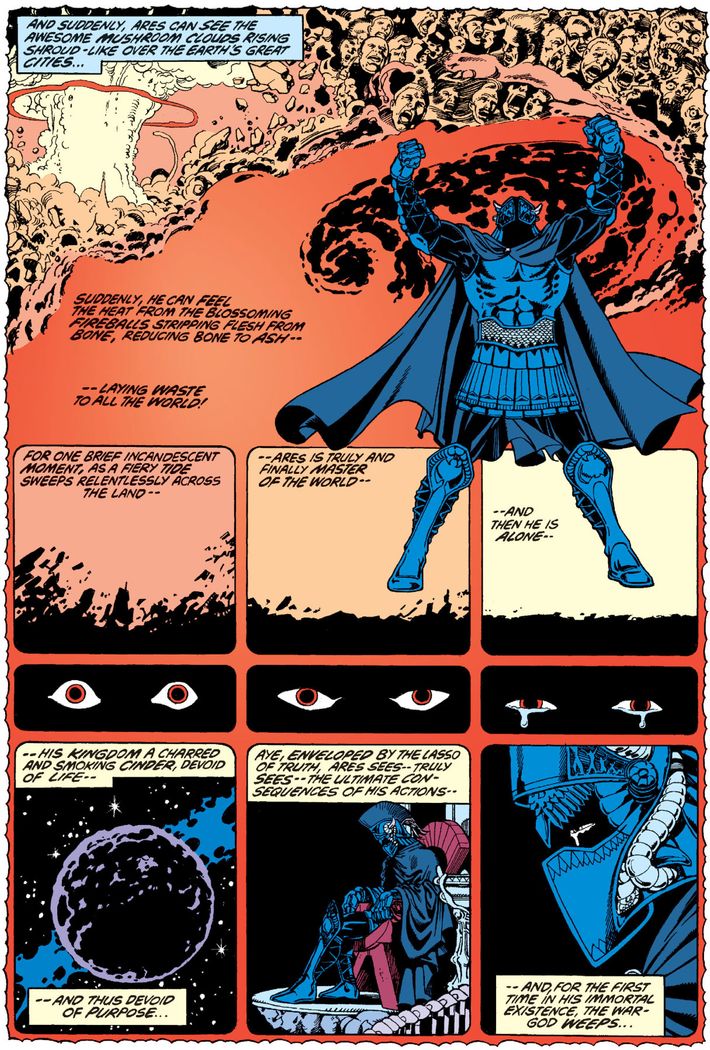

Or take, for example, a page in which Ares has a startling vision and is moved to tears. The bottom portion of the page has a nine-panel grid — three by three — and you’re tempted to think you should read it by going across the first row, then across the next row, then down to the final one. But relax your gaze and you’ll see that it can also be read as a series of columns, with each stack of three showing three aspects of the same moment from different perspectives. It’s all easy to consume, yet still experimental for the practice of sequential art, especially within the superhero corpus.

By the end of that 14-issue introductory saga, we’ve seen Diana become wholly unlike the brooding Batman or the grinning Superman. She is something else — something compatible with those two, but still separate. She’s less of a superhero than she is a kind of holy ambassador. “She told me she did not believe the point of her mission to Man’s World was to become a costumed crimefighter,” a character muses of Diana at one point. “That, she said, implied violence condoned by society in the name of order. Apparently, crime is unknown on Paradise Island, and order there is a state of mutual respect and love. Diana believed her true destiny was to teach the world the Amazon way.”

That she did throughout Pérez’s 62-issue tenure on Wonder Woman. For most of it, he was just writing it: “I’m just not fast enough to maintain a monthly schedule” of drawing, he tells me. He started getting fill-in pencilers to work with his layouts during the second half of that first big story, then stopped doing art altogether after the 24th issue. Though the entire run is regarded as a classic, it’s those first 14 issues that remain the most compelling — and accessible, in that they’re available in a single, recently issued volume called Wonder Woman by George Pérez Vol. 1. If you’re looking to get into the character before the film or want to dive into her printed adventures afterward, that book should be at the top of your shopping list.

Its legacy can be seen throughout the movie, though less in overt references than in a general tonal and thematic similarity. Jenkins’s film relies heavily on the mythological notes that Pérez first sounded, diving into Amazonian and Olympian history and naming Diana’s homeworld as Themyscira. As is true in the first Pérez story, Ares is presented as Diana’s ultimate opposite, like the Joker is to Batman or Lex Luthor is to Superman.

But perhaps the greatest similarity comes in the fact that Wonder Woman is presented as something of a noble fish out of water, new to our world yet passionately involved in saving it. As one character in Pérez’s run puts it while describing Diana, “I realized then what an amazing contradiction she is. On the one hand, nature’s innocent, her very voice like a warm, comforting breeze. On the other hand, desperate energy, forever searching for proper outlets. She is, in short, the living seed of change.” As anyone who sees Gal Gadot’s Diana, alternatively confused and indignant, plow through Europe can tell you, that’s a spot-on description of the big-screen incarnation of comics’ most famous woman.

For his part, Pérez is excited to see what happens to Diana at the cineplex. That’s unusual for him. He left the book in 1992 largely because his beloved Karen Berger had to go on maternity leave — though some creative differences also came into play — and he’s studiously avoided paying attention to the character ever since. “It’s my nature and it’s my flaw,” the 62-year-old says. “If I don’t like the person’s taste, I say, Oh my god, they ruined it, and if their taste is better than mine, I feel kind of betrayed, as well.” But he’s making an exception for the film, which he plans to see in his native Florida after its release. (He was invited to screenings in New York and L.A. but couldn’t make the trip.)

Today, the Pérez saga isn’t remembered as universally as its contemporaneous Batman and Superman epics. Perhaps it’s because the dialogue is somewhat stilted and unnatural — but that’s a feature, not a bug, as the story is trying to evoke the marble-built formality of the classics. Perhaps it’s because there’s very little in it that’s revisionist or deconstructionist — but just because something embraces genre tropes doesn’t mean it’s not ambitious. Or perhaps it’s simply due to the fact that Wonder Woman isn’t a character who is as globally beloved as her caped peers.

But if Wonder Woman, the movie, succeeds, the time might be ripe for a Wonder Woman revival. If so, Wonder Woman by George Pérez Vol. 1 deserves to fly off the shelves. There have been many creators who have done Diana justice — Gail Simone, Greg Rucka, Brian Azzarello, Cliff Chiang, and Phil Jimenez all leap to mind — but they all did their creating in the wake of Pérez’s resuscitation of the icon. “So much of where the character is now in DC’s pantheon and DC’s storytelling really owes its debt to what George did,” says Berger. Levitz is in agreement: “I think the legacy of the run isn’t so much innovation in the story. The legacy was proving that the character could be the center of good stories for the modern world.”

As for Perez himself, he sees his impact in two anecdotes. One was meeting Marston’s granddaughter, who, in Pérez’s retelling, told him, “You honor my grandfather.” The other was when a female writer told him she had read his run and was surprised to find out it had been written by a straight man. “These are the compliments I truly truly relish and made me say, Okay, I made a difference,” he says. “The fact that people are still referring to it now, that people who are complimenting or praising the movie are saying it keeps the spirit of the Wonder Woman that I defined? That’s a great legacy, y’know?”