For decades, a single word has followed filmmaker Luc Besson like an exotic cologne: spectacle. Critics, reporters, interviewers, and academics have used it — both admiringly and derisively — to describe the heady fantasias that the French writer, director, and producer has crafted for multiplexes around the world. Sometimes, they’re spectacles of violence, as in 1990’s La Femme Nikita, 1994’s Léon: The Professional, and 2008’s Taken (which Besson conceived of, co-wrote, and produced, but which was directed by his protégé Pierre Morel). Other times, they’re spectacles of sci-fi extravagance, such as 1997’s The Fifth Element and 2014’s Lucy.

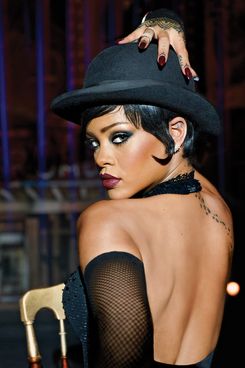

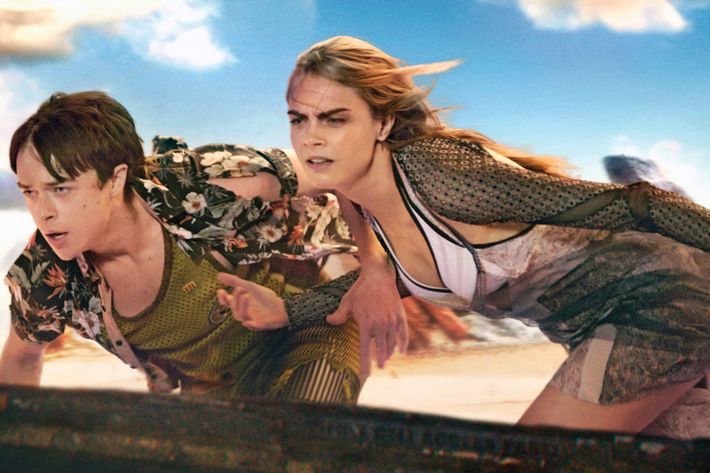

His latest, Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets, is firmly in the second camp. Based on a long-running series of French comic books by writer Pierre Christin and artist Jean-Claude Mézières, it’s a vividly colored epic that stretches across galaxies and dimensions, following the adventures of two hypercompetent space cops (Dane DeHaan and Cara Delevingne) on a mission gone explosively awry. The titular city, known as Alpha, is one of the more impressive CGI achievements in recent cinema, as are the myriad species that call it home. (A shape-shifting alien played by Rihanna is one.) We caught up with Besson in his sun-soaked Beverly Hills office to talk about lethal female protagonists, the perils of creating a film for international markets, and doing utopian fiction in an age of dystopias.

First of all, thank you for casting Ethan Hawke as a pimp. I didn’t see that coming. How’d you convince him to do that?

We’re friends, and I said, “Do you want to come and have like two, three days of fun?” And he said, “Yeah, sure.” He didn’t even read the script. He said, “What’s the character?” I said, “He’s a pimp.” And he said, “Cool.” He got to work with Dane and Rihanna, and it’s a nice three days in Paris.

Speaking of which, what’s it like to direct Rihanna?

There’s two parts: before the shooting and during the shooting. She’s one of the biggest stars in the world, so to catch her is a nightmare because, like, you have a meeting with her sometime at 2 a.m., and you’re not the last one; there is another meeting after you. She has to record a song after, and then she has to fly back somewhere. Her life is the life of a superstar, so I was afraid of that a little bit. But every time I saw her, she’s so focused and open, with no ego at all. She’ll say, “Okay, what do you want me to do?” No distance, no, Oh, you can’t film myself from here or this angle. It’s the exact opposite. When we were on the set, the entire entourage stays out of the set. She doesn’t want the entourage. So that was a pure pleasure. And it’s not so easy, what she has to do.

Sure, she has that long, slightly insane dance sequence.

No, not only the dance, but just after — the scene where she says, “You really liked my performance?” She has this smile and this emotion. Some people doubt that she can act, but in the film, she proved that she can act.

In the past, you’ve said you feel like your movies are really built on characters. What, to you, is interesting about the characters of Valérian and Laureline, the DeHaan and Delevingne characters?

I like the fact that Valérian is not Schwarzenegger. He’s not Iron Man. He’s not the big guy. Most of the time he’s lucky, sometimes he says stupid things. He is very human. And I like the relationship the main characters have — the fact that Laureline is the boss.

Right, Valérian’s very much not a superhero.

No, he’s not. Like most of the time in couples, she’s the real thing. Take my wife, for example. She’s organized. The school, the doctors, the appointments; she knows the balance of the sheets. And I’m like, “Oh, yeah, can I help?” [Laughs] I like, in the big story, to have the little story of something very human. He can’t do anything without her. From the beginning, I didn’t want a superhero. Superheroes, they’re all in tights. I want somebody human. Take León [Jean Reno’s character from León: The Professional] for example. León doesn’t know how to read and write.

True.

The only thing he knows is how to kill. That’s all. But we like him. He’s a cool guy. And when he has to show that he can be the man, he’s the man. He can fight.

What did you like about the original French comics the story is based on?

It was out of the world at the time. You know that we have to go back to this time — there was no internet, no video games.

No Star Wars.

No Star Wars, no TV, at least in my home. My stepdad doesn’t want music, doesn’t want TV, doesn’t want anything. So suddenly, every Wednesday, to have these two pages in a comic book — that was just like the biggest escape of my life. I can be a cop in space and fight aliens and team up with this cute girl who was a hard ass. At 10 years old, it was really absolutely amazing for me.

Was it something that made you want to make movies?

No, but it participated a lot in my emotional education, because of the relationship they have and the fact that she’s the boss. At the time, in the ’70s, women are at home and they are cooking, and it’s all they do, and then suddenly you see this girl.

Why do you think you’re drawn to female characters like that?

I think I created a couple of men, also. [Laughs]

I’m not saying it’s the only thing you can do, but it’s something that’s unusual in action cinema.

I just try to give an interesting part to everyone, not just the man. I try to pay attention to the woman. We often hear women are the weak sex and the men are the strong sex, but I’m very interested by the opposite. What’s the strength of the “weak sex”? Because there are women who can defeat countries, like Aung San Suu Kyi, Burma’s leader. She fought Burma’s military, and she won. Also, I’m impressed by the weakness of the male. Take The Terminator, for example. If he started to sob because he misses his mom, I’m interested. Then he makes it human, and then I love the guy. But if he’s just big and says, “Hasta la vista, baby,” it’s okay for ten minutes, but I want more.

How do you think we get to a place where there are more lead roles in action and superhero cinema for women?

I don’t know. The first one that I remember was Nikita.

Who was it that made that one again?

[Laughs] I’m happy that it opened the gate a little bit. People said, “Oh, maybe we can do that! We can have a girl having a gun fighting.” It’s good.

Was it hard to convince people to let you do a female-led action movie like Nikita?

The film was French, so, no, it was not hard.

What do you mean?

I was very well-known at the time. I just got out from The Big Blue, and The Big Blue was a mega super hit everywhere, so if I wanted to film the phone book, they would say, “Yes.” I do remember that when I came with Nikita, they were very, very disappointed. They said, “You’re not gonna do The Big Blue 2?” And I said “No.” They didn’t understand why I was doing something so dark after The Big Blue. I just said, “Because I love to change, to explore. I’ve done The Big Blue, okay, it’s done, it’s great, let’s take another color. [Laughs] Let’s take the black, let’s go there.”

Nikita may have been dark, but I feel like your visions of the future are generally pretty optimistic. Sure, there are bad people in The Fifth Element and Valerian, but the worlds of those movies seem to be operating quite well, on the whole. Where does that instinct come from?

The future belongs to us — we will do with the future what we want to do. Why do we have such a pessimistic view of the future when it depends on us? If we are not happy with the future that we see, let’s change it. I’m not like a 4-year-old who tells you, “Life is beautiful.” I know that there are problems, especially with the environment. But let’s work on it. Let’s make it better. Alpha, the city of a thousand planets, is basically the United Nations. They’re trying to live together in peace and share the science they have. We think it’s hard between a couple of different races on Earth? Try it with 8,000 aliens, just try. We see Asian and black people, Muslims, and so on, and we’re like, “Whoa.” But okay, let’s imagine tomorrow there’s 8,000 different species coming from space. You come back to Earth and you say, “Oh my God, it’s easy. I love everyone.”

What was the biggest technical challenge for the film?

I think the biggest challenge was not technical. When you have the script, you have your story and an emotional print of the script, almost like a barcode. Then this piece had to take years, and you’re scared to lose the barcode, to lose where we are, emotionally. Because the film is in one day.

So how do you meet that challenge?

I have a few tricks. Like, I always come first on the set, but before that, I read the script every morning until what we have to shoot. If we shoot here, I’m reading everything from the first page to here, to remind me where they come from. Second, in the morning, I put on music, but I always put the same music, because the … [makes ticktock sound while wagging finger back and forth].

Metronome?

Yes, it puts you back where you were with your feeling when you wrote the thing. It’s a mechanical way, through sound, to go back to the place. You try, in fact, to memorize everything about where you were before, to start your day, so you’re on the same path.

What was the music that was inspiring you during this?

It’s not inspiring. You just have to take one and then use the same for two years.

Ah, so you’re kind of sick of it by the end of the shoot?

Yeah, a little bit at the end.

So what was the playlist for Valerian?

There’s only one album for almost three years. It was Amy Winehouse. The last album.

How grim!

I think the charm and the voice, and it’s a little jazzy also, the album, which feels good with the film.

You cast a couple of actors in the lead parts who are not huge action stars. Was that intentional?

I just try to cast the best actors, always. Sometime it’s someone known, sometime it’s someone unknown. When I met [Dane DeHaan], after 30 seconds, I knew it was him. The blue eyes, the tone of the voice, the smile, the charm. As for Laureline, she’s very determined, very powerful. She’s full of life. And Cara, she’s like a kangaroo.

A kangaroo?

Yeah. She’s like, Moing-moing-moing-moing-moing! when she comes to work. So focused, so dedicated.

A word that gets thrown around a lot in discussions of your work is spectacle. Do you see your films as having a lot of spectacle in them?

No. I don’t know. I will probably start watching what I’ve done when I’m 75, with my friend Jean Reno, and [frequent score composer] Éric Serra, we have a log on the fire and we say, “Let’s have a look at what we’ve done so far.” But at this moment, I’m just lucky to be able to do films. So lucky. So I’m just enjoying it and working more. Since I finished the shooting [of Valerian], I wrote three scripts already.

Three!

I couldn’t stop myself. I just wake up in the morning and write.

Are they things we wouldn’t expect to see from Luc Besson?

Probably, yeah. I was not expecting to see it from me, so … [Laughs]

Do you ever think about how your movies will play in China or other major markets abroad? Is that something that goes into your thought process at all?

It never comes in.

You hear stories about directors having to change things to appeal to the Chinese market.

My feelings go out to them. [Laughs] I don’t even know what you’re talking about. It has no influence on me at all. I’d rather not make a film than not make the film I want to make.

The only thing that an artist has to do is to open his skills, and his skin, his ears, his eyes, and he has to be part of the global movement. I learned that a long time ago. Once, this Korean kid, he was like 14 years old and he had a red Mohawk, and he approached me really aggressively and he said, “My favorite film is [Besson’s 1985 film] Subway.” I say, “Okay, chill. First, I’m your friend — peace.” Then I said, “How old are you?” He said, “14.” This boy was not born when I made Subway. Then decades after it came out, a 14-year-old Korean boy with a red Mohawk says it’s his favorite film. Did I know at the time that it would happen because I’m global? It makes no sense.

So you don’t think there’s any logic in that?

I think it’s totally wrong, and all the people pretending to study the global market are most of the time wrong, and if you watch the numbers, you will have to explain to me why there are many films that cost between $100 and $200 million, which flopped, made by people who think globally. Who are in the meetings to green-light the film, with the script that no one read, and because there is a star, because there is this or that, because it’s a franchise — all these numbers get put together to make them think that it’s global. The reality is totally different. There’s a generation every four years. Every four years, there is a new generation that no one understands.

Every four years?

Yeah, because from 0 to 4, you don’t watch film. At 4 years old, you start. You have a generation with every 4-year-old. I have my daughter, and I’m saying, “Oh my God, that Facebook is big.” The 11-year-old says, “No, that’s for old people. I’m on Snapchat.” The only thing that an artist has to do is to open his skills, and his skin, his ears, his eyes. When I do something in a film, if I crack a joke, it’s because it makes me laugh. And if I get this guy or this girl to play the part, it’s because I love them. That’s the best chance you can have to be global, and that’s the only way. Every time you think, “I hate this part, but people are gonna love it,” it’s like, really? You think the people are different than you?

Do you pay attention to the critical reception of your films?

The Fifth Element was not very popular in the U.S., and the critics were very hard on the film. They said, “What’s going on? We don’t understand.” I always respect that, and say, “Okay, some people love it and some don’t.” Then 15 years later, in some articles, the film is a classic! They did a big show for the 20th anniversary and it sold out the tickets in, like, ten minutes. You just have to be who you are and try to be honest. Look at all these painters who died poor, and now they are in museums. I’m not comparing myself to them; what I’m saying is you just have to follow a kind of honesty or a kind of truth of what you want to express.

You can make a little bit of an adjustment, like, “Can I have $200 million to make the film?” “No.” “All right, so, how much I can have to make the film?” “You can have $180 million.” I take the 180 and I do the film for 180. It’s little bit of concession here and there to help the things to be made. But on the source material, on what you want to say, if you try to be global, you’re fucked, honestly. Avatar arrived, and for almost two years, all the sci-fi films after Avatar flopped because they wrote the thing before. [James Cameron] put the film to such a level that it’s like, “Guys, you have to change your storytelling now.” I was almost ready to go with Valerian, and then I saw Avatar. And I threw the script in my garbage and I started again.

Why?

Because it was not good enough.

What did you see in Avatar that made you think you had to do Valerian differently?

I didn’t take enough risks in the script. I was too conservative, maybe too polite. I just had to not be scared. You do what you have to do.

At your company, EuropaCorp, do you have a guiding philosophy? Is there something that you think you guys want to do that other people don’t do?

No.

No?

No.

Okay.

We just try to do the films we like, that’s all. It’s as simple as that. You always have a 50 percent chance of winning and 50 percent of losing, so at least if you do a film that you really love, and then at the end of the day it doesn’t work so much, you’re sad but you’re not dead, because you still like the film. And in five years, everybody will forget numbers, and you will just have a DVD. And then some weird Korean 14-year-old will discover the film. [Laughs]

When you were 14, what was a film that had that effect on you?

The two that hit me, the first one was One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. I was just in shock. You’re 16 years old, you’re trying to understand what life means, and there’s someone who says, “The ones who are crazy are not so crazy, and the ones who are supposed not to be crazy are crazy.” Suddenly your vision of life goes pfft. It was very educational for me. The other is A Clockwork Orange. Those were the two where I was like, “Whoa.” And A Special Day, by Ettore Scola. With Mastroianni and Sophia Loren. That was amazing.

And that’s what made you want to be a director?

It’s not a film that made me want to be a director.

What did make you want to be a director then?

I went to a set to give a hand, and I fell in love with the set.

With the set?

Yeah. I was 17, and not feeling secure with my life. My parents divorced and put me in boarding school. I was just fragile, and I came on a set. It was a short film, and this girl comes and smiles and says, “What’s your name?” I said, “Luc.” “You’re here to help?” “Yeah.” That’s all they ask me. “You want to help?” There is no name tag or family checkup or anything. It was just like, if film is your king, welcome to the kingdom. That was a revelation for me. I said, That’s the life I want. I went back home, and on a Sunday night, I said to my mom, “I want to make films. Not as a director but I want to be in the movie business.” And she said, “Yeah, we’ll see that later.” I said, “No, no, no, I’m quitting school tomorrow and I’m going to be on the set.” She said, “No, you’re going to finish your year.” And then the day after I took my suitcase and I left. I was 17. A little stubborn. [Laughs]

So it was like some kind of alternative social arrangement for you, one that was more egalitarian because everyone was devoted to the goal of making the movie?

Yeah. Just for the beauty of it. I love that. I don’t want to be in the business [part]. The funny thing is, I learned on the way to buy my freedom. I got lucky. I made a couple of films at the beginning, and they were very huge, so I got this money coming and I didn’t know what to do with this money because I never expected having money. I was very embarrassed with it, so I bought a house for my mom because I don’t know what to do with it.

Well, one thing you’ve done with the money is make other people’s movies. How do you know if someone deserves your production money for their film?

There’s two things: There’s the script and the guy. If it’s a guy who wants to direct, I will probably ask to see if he has a couple of short films; even with a telephone, it doesn’t matter, you can see if the guy is talented. I will see first: What are his skills? His angle, does it bring something? Is the guy fresh? Does he have a special way of telling things? And then, if I see that the guy is talented, I will be very interested by the guy. It’s like, if you’re the national trainer for U.S. tennis and you go and you see 14-year-olds playing tennis, if you’re not able to know if a player is going to be good, change your job. You should know if the guy is talented. It’s the same for me. I’m here since I was 17 years old, so I can smell and see if the guy has the abilities. Most of the time when they’re pretentious and they have sunglasses and they say they’re going to beat this guy, and they’re going to do this, and they’re going to do that, that’s a very bad start. Most of the talented ones I’ve seen, they’re very calm, they’re very polite, and they usually are very nice.

What was the last movie you saw that made you think, “Wow, this director is really going places”?

I didn’t see so much films recently.

You don’t have time?

No, I don’t.

What was the last movie you watched at all?

That I remember?

I take it you’re not the kind of person who goes home at the end of the night and puts on a movie?

No. I’m going to bed at nine.

At nine? That’s crazy.

I wake up at 4:30. I’m writing in the morning. I don’t like the night. I love my bed.

What do you do to unwind at the end of the day?

Un-what?

Sorry, it’s an American idiom. Like, what do you do to relax at the end of the day?

At the end of the day I’d love to come back home and listen to the kids. I’m fascinated by the stories they have about the relationships they have with others. There’s always drama over nothing, and I like to hear the story.

*This interview has been edited and condensed. A version of this article appears in the July 10, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.