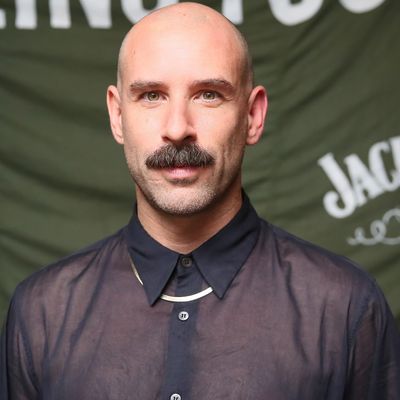

You may not know Ryan Heffington’s name, but you’ve almost certainly seen his work, and have possibly even tried it out in your living room. He’s the choreographer behind Sia’s videos with wig-wearing Maddie Ziegler (including “Chandelier,” “Elastic Heart,” and “The Greatest”), and has worked on movements for Baby Driver and The OA.

His latest project, Seeing You, is an immersive dance-and-theater performance that follows a group of friends from the early days of World War II to the dropping of the atomic bomb; it runs through the end of the month at the High Line Park. The show includes “maximum-impact choreography,” where the audience is invited to join actors at the dinner table, are hollered at in basic training, and hold up bomb parts while mad scientists strip down to their underwear and spray each other with blood. Heffington spoke with Vulture about putting together the show with Sleep No More producer Randy Weiner, his hand-heavy choreography, and Madonna’s influence.

How did Seeing You come together?

The Frank Sinatra estate reached out to the producers about doing a project based on Frank’s work. So the producers brought on Randy Weiner as the director, and Randy had the idea of doing something very different from what people normally associate with Sinatra. He was like, “Let’s talk about his contribution to culture around World War II. What does his music mean to people?” That’s where I think it originated.

I wouldn’t have made that connection between the production and Sinatra — his song “I’ll Be Seeing You” bookends the show, but there are a lot of dark elements in between, more than one might normally associate with him. Was the Sinatra estate onboard with the direction you took the show?

Absolutely. That’s where we wanted to go with it. Anything typical wasn’t of interest. When we presented the workshops to Warner Music reps, they were like, “We love this. Do what you want to do.” That was totally not what we were expecting. They gave us their okay, and from then we had our freedom. We also never had a script, which was liberating but also extremely challenging, and we made constant changes with input from the performers questioning the intent of their characters and the story.

Did you have any choreographic inspirations or starting points?

I was lucky enough to curate the soundtrack, so I got to choose my favorite songs and develop moods for different sections. But as for specific inspirations? Well, yeah: [Laughs] Madonna’s Blonde Ambition tour, the “Express Yourself” video, with all the dudes doing push-ups in heavily saturated ’80s lighting.

Oh my god. I didn’t make that connection until you said it. The set’s elevated platform; the grimy, industrial feel.

Yeah, with a bit more of a punk edge for the soldiers in the basic-training section and the blood-drive nurses.

How do you choose your projects?

Things I haven’t done before are of interest to me. Take Baby Driver — like, “What? Choreograph an action film? Sounds strange, sign me up!” At this point in my career I lean towards projects where dance is a very integral part. If people aren’t going to be drawn to that element, I don’t really want to do it. I don’t want to do backup movement, stuff that’s under the radar.

With projects like Baby Driver or The OA, did you find that it’s more interesting to work with nondancers versus professionals?

I thoroughly enjoy both experiences. My job when I work with nondancers is to make people comfortable in their bodies. Once you do that, they’re more willing to give and experiment. You get different qualities out of people that don’t have strict technique. When these differences are celebrated and this flexibility is allowed it’s pretty magical.

Although, with The OA, we had a very specific vocabulary. The approach had to be different. We discussed shapes and visual narratives. Like: Your fingers are dripping with water, what does that look like? People can envision that.

You have to become a translator of sorts.

Absolutely, and you have to be creative.

What was that process like for Baby Driver?

I was typically dealing with very specific timing, because an entire fight scene would be choreographed to music: This character’s gun would be firing on this count, and the next couple counts would be someone else. I love Edgar’s mind. He’s a genius and so meticulous. I’m usually hired to create and deliver something that’s based on my aesthetic and my influence, but this time around, for the most part, I was there to articulate his vision, which was really fun. But when I’d work with Ansel [Elgort] in the apartment scenes, that was much looser and more organic. He’d be dancing around the apartment, and he’d do what he’d want to do. The two approaches were at opposite extremes.

Your choreography makes a lot of use of the hands and the face. Is that something that you made a point to emphasize?

I’ve developed that over the years. I’ve seen so much dance that has stunning, beautiful physicality, but a lot of it was … emotionless?

Yeah, in a lot of dance, the focus is on the arms, legs, and torso — the hands and face aren’t usually the main attractions.

Exactly. And the narrative doesn’t become as direct as it could be. The face relays so much information and so many emotions, and I was like, it’s part of the body — why don’t we utilize that in dance more? Just through one facial tweak I can tell a whole story; I can enhance or change a narrative with a single glance. It’s about creating realistic emotions that people can connect with. Imagine a photograph of your lover in pain — what does that look like? That’s exactly what you should create with one split second, so people can recognize it and relate to it. That’s why there’s a lot of intrigue with my work — because people recognize these human gestures. It’s not super high-concept art that leaves you thinking, I don’t know what the fuck that was supposed to say.

Those movements are also easier to connect to. Not everyone can move their arms and legs and torso in a certain way, but pretty much everyone can manipulate their fingers or mimic a facial expression. It makes your work accessible.

Absolutely, and I think about that a lot, because dance can be super isolating. I love the fact that so many people were attempting the “Chandelier” choreography. They see this person doing stuff that they understand, but Maddie is also superhuman as well, so you throw that in and it’s like this new strange cocktail that people are drinking. That choreography is hard but people felt empowered enough to try it. That’s what is so beautiful about it. People just really got it.

What are you working on right now?

I’m collaborating with Sia again, and I’m doing a couple live performances with Opening Ceremony for New York Fashion Week in September. Right now I’m working on a project with some Broadway stars and they’re like, “This is weird.” I’m like, “I know! But isn’t it great?” And they’re like, “Yes! But it is so strange.”

This interview has been edited and condensed.