Each month, Boris Kachka offers nonfiction and fiction book recommendations. You should read as many of them as possible ÔÇö but only after reading two great August books by our staff: Adam SternberghÔÇÖs absorbing comic dystopian thriller The Blinds and Carolyn MurnickÔÇÖs memoir The Hot One, about a friend who drifted away and was later murdered.

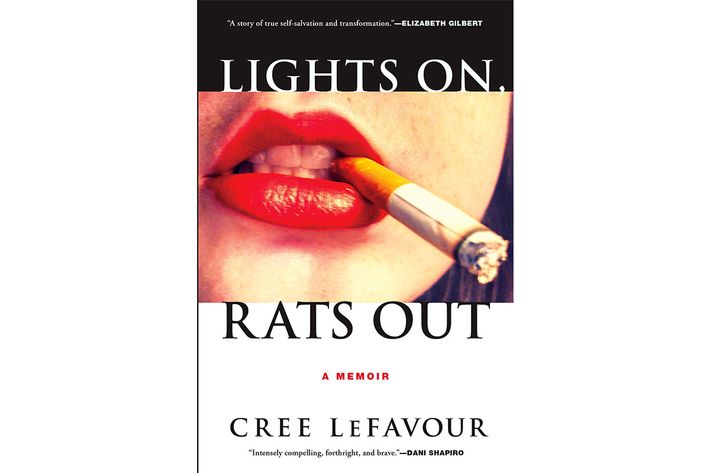

Lights On, Rats Out, by Cree LeFavour (Grove, Aug. 1)

Some memoirs descend into self-therapy or self-glorification, but LeFavour glorifies therapy as a happy ending ÔÇö albeit a very slow fix. Her eloquent, irreverent, graphically precise story begins with bad luck: the daughter of a neglectful chef and a freewheeling mother who runs off, leaving the kids to raise themselves, LeFavour grows into a bulimic young adult with a bad cigarette habit (she uses them to self-administer third-degree burns). The chronicle of her slow climb out, with the help of Dr. Adam Kohl, is enriched by the psychiatristÔÇÖs own notes.

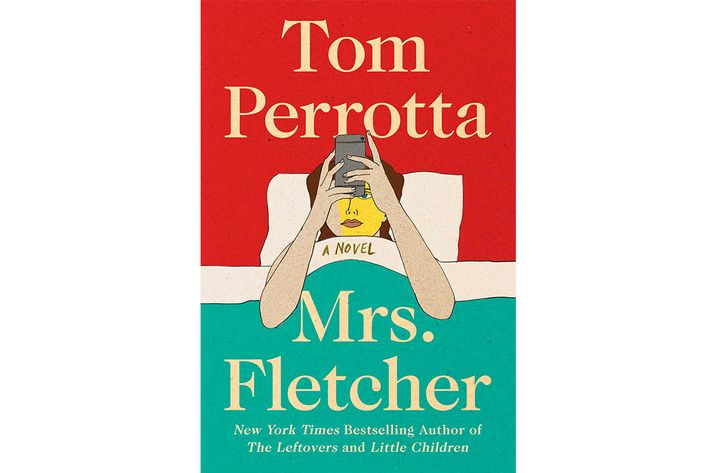

Mrs. Fletcher, by Tom Perrotta (Scribner, Aug. 1)

In his first novel since The Leftovers ÔÇö both the dystopian novel and the darkly absurd HBO series he co-created ÔÇö Perrotta returns to the suburban discomfort food that made his name (Election, Little Children). Spurred by middle age, an empty nest, and a mysterious booty call, the aspiring MILF of the title explores her sexuality while her bro-ish son, a freshman in college, does the same in a very different way. Neither really knows how to flirt with much more than disaster, but the authorÔÇÖs satiric talent is applied with a fine, gentle brush.

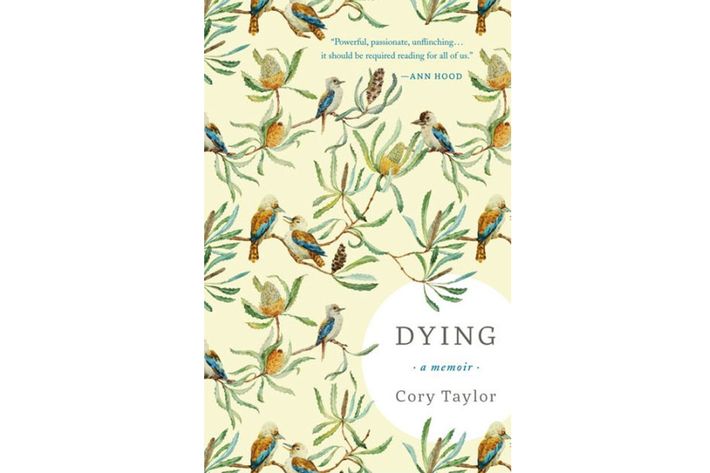

Dying: A Memoir, by Cory Taylor (Tin House, Aug. 1)

Taylor, who died of cancer last year, not long after this was published in her native Australia, left behind one of the best entries in a grim genre. Her language is sharp and clear, her senses heightened by the feeling of time running out. She dwells not on the picayune details of dying but on its inevitability and the shadow it casts over life. Inspired in a way by her illness, Taylor recounts her own vivid childhood ÔÇö a story colored and shaped, like all stories, by its final destination.

Beast, by Paul Kingsnorth (Graywolf, Aug. 1)

With the second book in a planned trilogy, Kingsnorth is becoming an existential David Mitchell: a versatile weaver of the seemingly unconnected into a tapestry realer than reality. His first novel, The Wake, featured a resister of the Norman invasion named ÔÇ£buccmasterÔÇØ and was written in ersatz Old English. Beast stars a hermit named ÔÇ£BuckmasterÔÇØ in a contemporary England where something is definitely off. He stalks an elusive (or illusory) beast in hypnotic language that makes the plot almost secondary. Book three will take place in the distant future; hopefully it will be published much sooner than that.

Stay With Me, by Ayobami Adebayo (Knopf, Aug. 12)

The Nigerian debut novel that earned Michiko KakutaniÔÇÖs last rave review ÔÇö and deserved it ÔÇö slyly melds African literary traditions with our own penchant for suspenseful split narratives about the lies husbands and wives tell each other and themselves. Childless for four years, Yejide reluctantly agrees to let Akin take a second wife, only to find herself pregnant by another man, while the younger wife ends up dead. Secrets unspool as Yejide and Akin tender separate confessions, leaving the reader to piece together the truth against a fascinating cultural and political backdrop.

Freud: The Making of an Illusion, by Frederick Crews (Henry Holt, August 22)

The powerful and thorough takedown of Sigmund Freud you may or may not have been waiting for casts the founding psychoanalyst as a far better self-promoter than scientist, even by the standards of his day. Much of FreudÔÇÖs work has already been contested or debunked, but Crews examines the role of his heirs and acolytes in burnishing his deeds and hiding evidence of his faults. To Crews, FreudÔÇÖs experiments and free administration of cocaine should have banished him to the status of occultist rather than a pioneer who invented the subconscious (which he did not).

Autumn, by Karl Ove Knausgaard (Penguin Press, Aug. 22)

Some of the best parts of KnausgaardÔÇÖs six-volume deep dive into the writerÔÇÖs most important subject ÔÇö himself ÔÇö were the moments he looked outward, into the books he read or the things he saw. Autumn, to be followed by three more season-themed books, gives the external its due. Beds, tin cans, vomit, and migrating birds, as well as more abstract qualities like forgiveness, are examined in short essays in his inimitable voice ÔÇö profound earnestness, alternately cranky and ecstatic, with a Nordic half-wink of self-parody. No one dotes on details like Knausgaard.

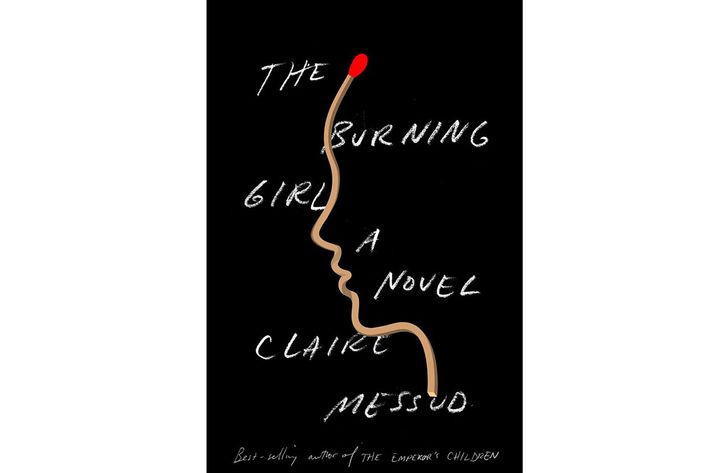

The Burning Girl, by Claire Messud (Norton, Aug. 29)

Quieter than both The EmperorÔÇÖs Children, her best known and funniest novel, and her last one, The Woman Upstairs, which plumbed the depths of female frenemyship, MessudÔÇÖs latest trades instead in inner turmoil ÔÇö naturally, for a story of young feminine adolescence. The crucible of junior high school breaks the childhood bonds of Cassie and Julia ÔÇö the former more popular but ultimately headed for darker waters. When her home situation verges on crisis, it might be up to Julia to save her, even as she realizes she never really knew her at all.