When LCD Soundsystem called it quits in 2011 after three masterful studio albums and a joyful, teary, and allegedly final concert at Madison Square Garden, it seemed as if the band’s mastermind James Murphy had achieved that rarest of music-world maneuvers — the graceful bow-out. But just underneath the meticulous dance grooves and hyper-self-aware lyrics of LCD’s music was always a deep vein of punkish restlessness. Thus, perfect endings be damned, the band’s forthcoming reunion album, American Dream. “I shed any ambivalence about coming back a while ago,” says Murphy, squinting against the sun pouring in through the window of a Williamsburg hotel room. “Whether or not other people have, I can’t say.”

How much of stopping LCD Soundsystem back in 2011 was about trying to preempt self-destructing?

It wasn’t so much that. One of the big things that broke the band up for me, which I’ve become much clearer on over the years, was that I had no desire to be famous. I’d met a decent amount of famous people and thought, This is not a life that I want to live. The life I wanted was what I imagined the life of a respected scientist was like. I wanted to be able to get on a plane and have no one give a shit unless they were also a scientist: “That’s so-and-so. He invented a particular molecule. How awesome.”

Is that the life you have?

The life I live in this band is the best possible life of all the options for being a musician. Everyone in the band likes each other. We all like our crew. We’re fortunate enough to play where we want, within reason. We have great agents who are also our friends.

Even in just an emotional-perks kind of way, how much did you miss being in LCD Soundsystem?

I didn’t. I had a great fucking time in the years between the Madison Square Garden show and now. I got married, had a baby, made a film, worked with David Bowie, co-produced an Arcade Fire record. There’s a lot of stuff I got to do that I really enjoyed that would’ve been absolutely impossible if I’d been in LCD. I only missed it when I would go see another band, but that’s a competitive thing. I’d be like, Oh, they’re just playing a fucking track from a laptop.

There’s nostalgia in the air for the early 2000s New York music scene that LCD came up in. Does the city still carry any of the sense of creative possibility that it did for you back then?

Not really.

How come?

It’s just how I feel. The city doesn’t feel interesting. It’s too expensive. There’s a lot of really normal people here which is fine, but when I moved here [from New Jersey] in the late ‘80s all my friends were like, “You’re fucking crazy.” Nobody thinks you’re crazy for moving here now. Like, zero people. Instead they’re like, “Oh, that’s interesting. Why are you moving?” “Well, I got a job with Schwab.”

So where would the 20-year-old version of you move now?

I don’t know. The internet means it doesn’t matter if you fucking live in New York. Why would you live someplace you can’t afford? Also, locality doesn’t seem to matter as much anymore. A scene is not a scene of people who know each other and borrow each other’s van. A scene is a style. You can be from the suburbs somewhere and be like, “I make dubstep.” Okay, great. That just means you’re working in a genre, not a scene. It’s a different kind of thing. But if I had to, I guess I’d tell a kid to move to Berlin. That’s where everyone seems to be going.

Isn’t there something good about being able to feel a part of a scene or a genre or whatever you want to call it even if you live in a suburb in the middle of nowhere?

There is, and I think it’s a phenomenon that started to happen in the ‘90s. That’s when you started to get people in Vermont or wherever identifying as a “D.C. band” because they wanted to make music that sounded like it was on Dischord. That was the beginning of the end of locality — the end being you share things on Bandcamp and it doesn’t matter where you live at all.

I always wonder about the relationship dynamics after a band breaks up. Was there ever any interpersonal pressure to get back together? You hear stories about the Grateful Dead going on for years longer than they wanted to just because they felt responsible for everyone’s livelihood.

I don’t like the Grateful Dead but that feeling is a real fucking thing. You have people on the crew whose jobs are working with you, and you know that those jobs are good ones; but I wouldn’t tour endlessly and kill myself with a drug habit just because I wanted to make the people that worked for me happy. As far as the people actually in the band, [keyboardist] Nancy [Whang] would laugh and say, “You just one day said we weren’t doing it anymore so I thought, Okay, I have to figure something else out.” But everybody did things. [Bassist] Tyler Pope DJs and has his own label. [Drummer] Pat Mahoney has his own band and DJs. Nancy plays in the Juan MacLean. [Guitarist] Al Doyle is in Hot Chip and has his own band. [Synthesizer player] Gavin Russom has a totally other career as an artist. [Multi-instrumentalist] Matt Thornley became a coffee roaster. People were psyched to get back together, but I don’t think it was like, “Save me from economic doom.”

This is probably a naïve question: So why go to the trouble of breaking up the band at all? Why not use those magical words “going on hiatus”? You’d get all time off you needed without any of the second-guessing.

For the rest of my life, now matter what happens in this band, we’ll never “break up” again. One day we’ll just stop making music, but no one is going to say a fucking word about it ahead of time.

Going back to the subject of nostalgia, though —

2017 is to 2000 as 1977 is to 1960. In 1977, you could by all means have thought 1960 was a fucking long time ago and be nostalgic for that time. It’s just as valid of a thing to, today, be interested in 2000.

I’m sure in 1977 people had some distorted ideas about what was going on culturally in 1960. Is anything getting missed or distorted in how people remember the years in New York when LCD and DFA Records were getting started?

I was just talking to Nick Zinner about this, about how everybody thinks their time was important because it was their time. Most of the time people are wrong — because they can’t separate themselves from their time — but I don’t think we were wrong. New York at that time was special. There was something going on. It’s as valid a cultural era as the late ‘70s was.

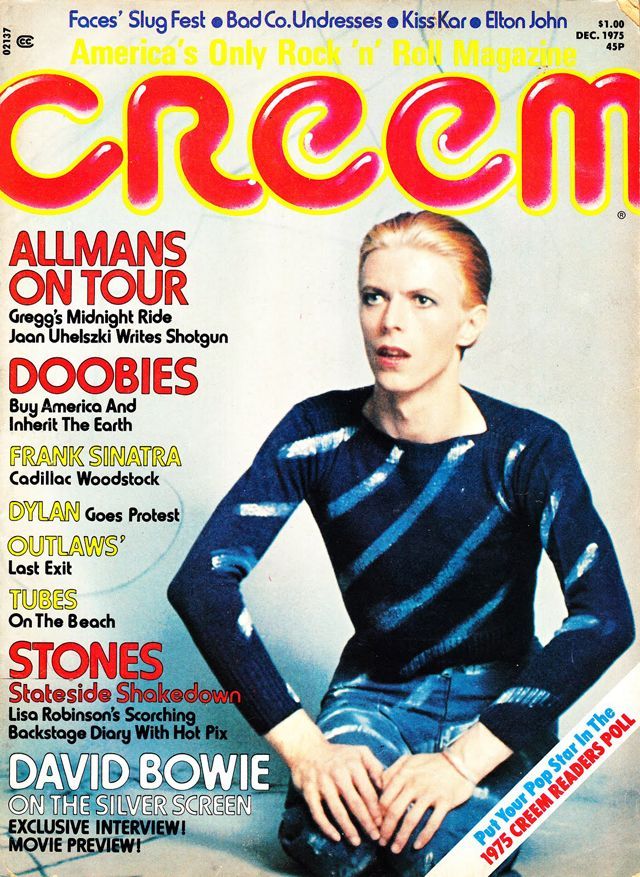

Don’t you think that it remains to be seen whether the records and bands that came out of that period will feel important over time in the way that, say, the Ramones or Parallel Lines still do? Karen O was talking to me once about how she’d read an old article in Creem or something about Blondie and Johnny Thunders and all the New York stuff, and the gist of it was, “Is this real? Isn’t this just hype?” I’m sure if you asked that same journalist today, he’d say, “Yep, it was real. That was the time.” But people had the same skepticism about the early 2000s, about the Strokes. Well, fuck that. No. What happened was real. There was special shit going on.

I don’t doubt it but how does someone ever know that they’re not just idealizing their past?

There’s always a good way to tell how much special shit was really going on at a given time, and that’s by how many bands self-destructed. Because if there’s nothing special going on, bands don’t self-destruct, they just break up and everyone goes and gets a day job. Lots of ‘90s bands didn’t self-destruct; guys in indie bands just stopped being guys in indie bands because what they were doing didn’t matter — they didn’t freak out and ruin themselves. Instead after awhile they just were like, “You know, I don’t want to do this.” But a lot of the early-2000s-period bands went super weird and freaked out. The Liars completely changed direction. The Strokes kind of self-destructed. The Rapture kind of self-destructed. That’s a good sign to me that something interesting was going on.

How much of that had to do with particular personalities and how much had to do with outside pressure?

Okay, when people say “hype,” that’s a part of it. There’s only so much that can happen when no one is paying attention unless you’re a weird outsider artist who dies and then someone finds your chicken coop full of amazing, weird paintings of naked babies that live in a fantasy world — but that’s not how music happens. Music is a relationship between the people making it, journalists, and an audience. It’s this whole affair, not a solitary thing. The hippie ‘60s musical movement isn’t important because the music is good — a lot of it is garbage — it’s important because a lot of people were paying attention.

But 50 years later, isn’t the music from the ‘60s that people still listen to being listened to because it’s good?

That’s not really the point I’m trying to make. I’m saying that people paying attention to music at the time the music is being made changes the music. Sometimes it makes the music more interesting. Sometimes it makes it bad. A lot of bad music got made simply because people in bands thought they had to be hippies.

All that post–Sgt. Peppers’ phony psychedelia.

Yeah, and a lot of really good music got made because people were emboldened by success and then they had to decide if they were going to self-destruct or make something amazing or some combination of the two, which is what most of the important bands did. And you wouldn’t do that if you were just a local band that never get any outside attention. It wouldn’t happen. You’d just go get a normal job.

Not to harp on this stuff, but how much of ending the band after selling out Madison Square Garden was about going out with a grand gesture?

I don’t know. Perception is really funny. I went to see Metallica the other day at Giants Stadium. There was like 70,000 people there. Sell 70,000 thousand tickets in fucking New Jersey, to people who know every single lyric of your songs — then we’ll have something to talk about. Madison Square Garden is probably 18,000 tickets. That’s a lot of fucking tickets, but that ain’t shit on what Metallica can do.

So having played that show doesn’t feel, now, like a special culmination of the band’s career up to that point?

Well, at that time there was a perfect storm that made me break the band up. I’m going to back way up for a minute: I went to a good high school in a shitty town in New Jersey. The vast majority of kids in my school went on to college. That’s just what you did. And I remember feeling like, No, I’m not doing that. The idea that college was next, that it was a given, meant it was of no interest to me. So I didn’t go. I took a year-and-a-half off. I was a kickboxer and I worked in a bookstore and I worked in a phone center and I was a bouncer at a punk club and I had a band — all this dumb shit.

Where’d you live?

At my parents’ house. I got my own phone line.

Pretty sweet.

Not really. After that year-and-a-half my dad said, “You have to get out of this fucking house.” Okay, fine. I’d just needed to break the feeling of expectation in order to be able to approach college without pressure. So I moved to New York and I went to NYU.

Can you make the connection between your decision to go to college and to break up LCD Soundsystem a bit more explicit? I’m not quite following you.

There was a sense of finality to what was happening with LCD Soundsystem that depressed me. After This Is Happening, I suspected that our next record would be the big one. You keep going long enough and your least interesting record, your Little Creatures, is the one that becomes humongous. The end of the Talking Heads to me was Speaking in Tongues, and Little Creatures was just the next one. It was the one the mass audience was ready for. I was suspicious that something similar was about to happen to us. I wouldn’t even have had to make a great record; I just needed to make something passable, to not fuck up. All the other bands that had been our competition had fallen down except for Arcade Fire. Everyone had just fallen over and died. So we were just standing here, like, Okay, I guess we’ll become really big now. I didn’t want it.

Why not?

I don’t want to be subsumed into popular culture and played on the radio next to some garbage music. I don’t want some kid’s first experience with my band to be because they heard us on the radio and just liked it more than they liked some other fucking song.

Isn’t it a little willfully perverse to try and maintain a connoisseur’s attitude about who and when someone should hear your music.

Yeah, but that’s how I’ve always been. And those kinds of feelings got mixed in with the fact that we had booked this Madison Square Garden show and then realized the show’s promoters had no faith in us. They were trying to come up with big-name openers for us because they didn’t think we could sell out the place by ourselves. One of the openers they suggested was Big Boi from Outkast. Why on earth would Big Boi open for us? Big Boi was in one of the biggest, most important hip-hop — no, one of the biggest and most important acts of all time. It didn’t make any sense. But behind that idea was the promoters’ belief that we just weren’t going to sell any tickets unless there [was] some extra element. So I got mad on the phone with them about it. I was like, “Well, how about it’s our last fucking show?” And I hung up the phone. Then I was like, I guess that’ll be our last show then.

That almost makes the decision to play a big good-bye show sound sort of cynical.

Maybe it is. I mean, I don’t know. I was just mad. What’s always been nice for me about being in this band is that we don’t want anything. I don’t want anything from you, Madison Square Garden. I just wanted to play a show, you know what I mean? I don’t give a shit, man. I remember when we got nominated for a couple of Grammys for the first album and it just depressed me.

I don’t think I realized how neurotic you are.

This is news to you? The Grammys depressed me because, well, a couple of things. My parents had died.

Well, that is a depressing thing.

They died in 2001 and they never saw any of the band’s success. I was into punk rock my whole life. I never listened to the Eagles. I never listened to things that were getting Grammys. So getting a Grammy nomination wasn’t bad, it just wasn’t meaningful. But it would have been a real thing to my parents, a symbol that I was not a failure. Anyway, the thrust of all this is that what makes the band function is that on some level people know we’re operating slightly differently than most other bands. Our goals are different.

Are there any similarities between your band and Arcade Fire that account for why you’re both still going?

It’s funny because they weren’t in our cohort at the beginning and now they are just because we both got started around the same time. There are similarities in that we both seem to exist in our own little worlds, and we’re bands with a whole lot of people in them, but we’re very different. We’re using different tools.

Is it harder to find your lyrical subject matter the older you get? Win Butler really pushes Arcade Fire to address the big topics, which is admirable and also extremely difficult to pull off. Do you push yourself in any similar ways?

Not too much. I’m not a big-topic guy. I tend to like writing about things that are small or personal. There’s a limitless amount of detail in small things. There are a couple of times where I feel like a topic was handled completely correctly, and then I don’t want to go back to it. But that’s only happened a couple of times.

What’s an example?

“Losing My Edge” is one. I don’t think I would ever retread writing about that very particular thing because I feel like I got that right. “All My Friends” — I got something right. I’m talking about how these songs connect with people, not necessarily that I think they’re better written than everything else. They got their point across. It’s like if you’re a chef and you finally hit on a really good chicken dish. Then you can be like, “That’s it. That’s my classic chicken dish.”

This is tangential, but you co-own a wine bar in Williamsburg, and you put out your own coffee blend. There’s this idea, that wasn’t around in a widespread way when you were younger, that food culture is a cool thing for someone like yourself to be involved in.

It’s super weird.

Every once in a while I’ll catch myself saying something like, “I’ve had better burrata,” and I imagine the 20-year-old me hearing that and wanting to —

Punch the today-you right in the balls, yeah. I mean, my 47-year-old self wants to punch me in the balls sometimes when I say things like that. But, okay, coffee is something I’ve been singularly obsessed with since I was 21. Oh my god, in ‘92, I wanted a La Pavoni so bad. I was deeply nerdy about coffee back when it wasn’t a thing anybody else gave a shit about. Wine was something different. My friend, Justin, who was in a band called Pitchblende, got me interested in it a while ago, as a thing to learn about. I’m always puzzled by people who say, “I’m bored.” Fuck you — the world is endlessly compelling. Learn to make a chair. Figure out plumbing. Do pottery. Get into wine. But I didn’t see wine becoming worldwide hip phenomenon. I should’ve.

Is the fact that wine and food have become hip indicative of anything larger? In Brooklyn now it feels like you’re as likely now to meet someone making cheese as you are someone who plays in a band. It’s a strange shift.

I’m doing a pop-up restaurant — I don’t quite understand how we got here. Maybe it’s that we live in our phone and computer so we want to do something with our hands? Also, nobody can afford anything real. No one can buy a fucking apartment in this city so you might as well buy burrata. A plumber used to be able to buy an apartment. Now you can have an advanced degree from an Ivy League school and you’re still like, “I can’t buy an apartment but I did get this ham from Spain that my friend smuggled in. It’s totally illegal ham.”

There’s also something about how food culture — and I don’t include the makers and real experts in this — but how it’s literally about consumption that can make it seem so boring. You’ll talk to certain people who’ll say they’re a foodie and everything with them just reduces to “that food I bought sure tasted good.” The depth of the interest can feel so hollow.

It’s like if someone was into massages: “That massage was excellent.” Wow, good for you for thinking that. It’s also about people not wanting to be challenged. The way the world works now is so fucking weird. Like, we released the cover art for the new album — that’s a fucking thing bands do now: releasing the cover art. So we did that and there was a Twitter storm about people not liking the American Dream cover. And Newsweek — because nothing else is happening on planet Earth — posted an article about how some people on Twitter didn’t like the art for the new LCD Soundsystem record. Which is obviously a hot topic.

Nothing is more important.

North Korea be damned! This article is both one of the worst things I’ve ever read and one of the best things I’ve ever read. The writer’s description of how the art worked was so dead-on. There’s an incredible comment, something like, “This artwork isn’t just bad, it’s going into the Uncanny Valley. It makes me incredibly uncomfortable.” And then they wrote, “Maybe it’s intentional, but I don’t know.” You don’t know? You literally perfectly broke down the artistic mechanisms that were going on with that cover art! “On one hand it’s this happy sunshine sky, on the other hand it’s almost interrogating and unpleasant.” Hmm. Keep going, little tiger. You’re almost there. And in the end the problem was that the cover bummed the writer out. Oh, sorry. Is my job to make you comfortable? Am I supposed to go give you a hand job? Hidden in that article’s assessment was the implication that we now live in a world where art’s only job is to reaffirm people’s belief that they have good taste. Everyone thinks they’re correct all the time because their Facebook feed constantly reestablishes that they are. That’s a mind-boggling phenomenon. I remember growing up and people would say, “I’m not cool. I don’t know.” That’s gone. Some ding dong wearing wraparound sunglasses and a backward hat and nothing but Under Armour clothing is absolutely sure that they are fucking cool as shit, and there’s nothing you can say to make them deviate from that. It’s such a weird thing.

Has your idea of what’s cool changed?

It’s changed because cool has become uncompelling to me. It used to have some meaning. Iggy Pop at his Rock and Roll Hall of Fame acceptance speech, where he kept saying, “This is cool; and that’s cool” — you could see that the word “cool” had a specific, pretty hard-won meaning to him. At this moment in history it’s been emptied of meaning. I used to hate cool stuff because I was jealous of it. Then I thought I would try cool stuff to see if it was fun. Then I was cool. Now I’m just old. That’s the arc. Also, for me to try and be cool now … good god. I’m not going to dye my hair.

If people are disinterested in being challenged, like you just said, does that change how you approach what you do?

It doesn’t.

You say that, but that Newsweek article is clearly occupying space in your head.

Because it blew my mind! I wasn’t thinking, How am I supposed to make art now that this person doesn’t like my cover? If someone thinks my album cover is shit, that’s fine. But the fact that this person completely accurately broke down how the art was working and decided it was bad because it bummed them out? Even as a kid that’s not how I approached things. Yes, the Swans bummed you the fuck out. Raping a Slave — there’s no way that was not going to bum you out. Or how about Suicide? The band was called Suicide! Their album cover has bloody letters on it and the singer is hitting himself with the mike while he’s doing a weird Elvis impression and another guy plays slightly out-of-time organ over a beatbox! What on fucking earth is going on there? I wanted to figure it out. So I expect the audience to be bummed. I don’t expect somebody who can accurately assess what’s going on with a piece of art to also not say that maybe the thing bumming them out is also what makes the art interesting.

You’re famously obsessive about music — listening to it and making it. Is it helpful to have the band back just so you can have something to point your OCD tendencies at?

It’s easier to be obsessive about things other than LCD. LCD is hard to be OCD about because it involves humans. Breaking up the band caused me to recognize that I’m a musician first and foremost. I did other things but they weren’t like doing music. I didn’t understand that significance for most of my life. I was like, “There’s nothing special about me as a musician. I’m not a good guitar player, I’m not a good drummer, I’m not a good bassist, but I play all these things fine enough to make what I need to make.” So that led me to believe that I wasn’t actually a musician in some way. Instead I thought I was a “creative” person and music just happened to be what I was doing. It took me a long time to realize that I understand music better than I understand anything else. It wasn’t just another thing; it was the thing.

I rewatched Shut Up and Play the Hits the other night, and in it you have this line about how your goal for the band was to make a mark. With the benefit of six years away, do you feel like you accomplished that? And can you characterize what that mark was?

I don’t know how to characterize it. I guess I feel like we mattered emotionally to a decent amount of people. That’s all, and that’s enough. There’s somebody who gets married and wants to hear a song of ours when they get married. There’s somebody who has had a group of friends and there’s a song of ours that’s their song. That’s all I ever really could ask for.

No part of you was hungry for something bigger than that?

I try to negotiate that urge, because I remember early on recognizing I don’t want to be so, Oh, those are the people that like us and they’re the only people that matter. There’s something fun about trying to compete and be like, “I’m going to take on Jay-Z,” which is just ludicrous, but also healthy and optimistic. I like the idea that the Stooges weren’t just trying to play for a bunch of record nerds. They were like, “Hey, man, let’s go take on the Eagles.” Suicide was trying to make hits. There’s something beautiful about that.

It’s an impossible dream.

And it’s different for Americans. It’s not weird for English people to assume they can have a hit. The Human League came from the most spartan, dark, industrial music background and they were like, “We want to get a No. 1,” and there was nothing weird about it because England was such a smaller country where things shifted more quickly. Whereas here, No. 1s are reserved for Justin Bieber or Jay-Z. There’s just this handful of shifting superstars. In England there would be surprise No. 1s. Oh my god, the guy — what’s his name? From Orange Juice?

Edwyn Collins.

Yeah. “A Girl Like You.” Years after he was in Orange Juice and suddenly he has a hit. I just finished the Morrissey autobiography, which is an incredible thing — there’s 50 pages just on the Mike Joyce lawsuit. But you read it and you see how he was just obsessed with getting a No. 1, and it’s really about being an English musician. An American band, there’s no hope when you’re a kid in a band that you’ll get a No. 1 hit. “We’re going to get a charting single!” No you’re not. You might get a gig that people pay to go.

You talked a lot in the past about how the impulse behind the band’s music was a competitive feeling. What are you competing against now?

Well, we wound up in a very weird place. Not a bad place; a wonderful place. I don’t want to be in any other band and I don’t know that I’ve ever felt that in my life. When I was a kid I wished I was in Echo and the Bunnymen; I wished I was in Black Flag. I always wanted to be in another band. Then I suddenly looked around and I was like, There’s not a band that I’d rather be in. And as a band, we have this nice thing where we’re not trying to be for everybody, but there are a lot of people who want to see us and who support us. I don’t want that to make me complacent. I don’t want to be lethargic. You still want to have little bit of a knife-edge, and I think that comes out more as a live unit than on record. The world of recordings is really different now.

How?

People are like, “You have to push things forward.” How? Every sound has been made. I have records of stark, dramatic, minimalist techno. I have records where all the drums are distorted. So many boundaries are gone, and everything can be programmed so it doesn’t matter if you’re an amazing musician. You could be the most ripping crazy drummer and everyone is going to hear it as programming.

What are the implications as a musician when you think everything’s been done?

It doesn’t mean every song has been written or every type of music has been generated. But the advances have slowed down. For example, this new Katy Perry song [“Swish Swish”] she played on Saturday Night Live — it just sounds like ‘90s house. The ‘90s? It’s 2017! Imagine in 1987 making something that sounded like it was from ‘63 and thinking, Oh, I’m making something new. It would be deep retro.

It would be playacting. It’d be Sha Na Na.

You’d be fucking Sha Na Na! But now things are moving so slowly that something like house music, which is already well-trod territory by Madonna, bless her soul, is supposed to feel new. That is slow as shit. Compare it to ‘74 to ‘77, that’s Roxy Music’s Country Life to the fucking Sex Pistols. That shit progressed fast. Instead of things moving in a linear fashion, now they’re moving laterally. Instead of pushing yourself to make new sounds, you can just keep finding sounds that already exist that you just haven’t heard yet.

What’s the last music you heard that you’ve gotten really excited about?

Jay-Z, “The Story of O.J.” It was fucking beautiful. His voice sounded different, relaxed. He didn’t have as much of the “you’re crazy for this one, Jay” thing going on. The hook and then the little pause: “I’m not black I’m O.J.” — pause, pause, pause — “okay.” It’s a dense, complicated song. That and, you know the Roches? You know “Hammond Song”?

That song is incredible.

I’ve been listening to that as a file and I loved it. So I tracked down a pristine vinyl copy and I played it on vinyl in my house and wept uncontrollably. Seriously — wept uncontrollably. It was one of the most visceral experiences of a song that I’ve ever had. And the Fripp guitar on that?

Robert Fripp is someone who, as a person, you never want to like, but he’s just been involved with so much good music.

He’s such a fucking ding dong. I’m in King Crimson, I’m going to play sitting down. You want to smack him, but he’s so good. If all he’d done was “Hammond Song” and the riff on [David Bowie’s] “Fashion” you’d think he was amazing. But then there’s so much more amazing shit he did. In fact, we bought this old Roland synth guitar for tour that I kept seeing him play in videos. We got it for Matt to play all our Fripp-y bits.

Isn’t your music the result of that kind of lateral movement you were just talking about? You’ve never exactly shied away from adopting the sounds of your influences.

For sure, but I’ve always been a man out of time responding to what I find around me. That’s kind of why I have a hard time listening to new music, which is funny because I make new music. It’s just as exciting for me to find weird African dance records from 1981 as it is for me to find out what [a] new band is playing down the street in Brooklyn. I’m still digging around. But what we have now is like — how long has it been since Nirvana released Nevermind?

26 years.

Okay, and 26 years before Nevermind?

1965.

So in that span we went from the Beatles’ Rubber Soul to Nevermind. Do we think we’ve progressed in any sort of similar way from Nevermind to now?

You could argue that the move from Rubber Soul to Nevermind is —

Closer than it seems, I know. But the point is, I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with what Katy Perry’s doing. I’m just saying that instead of linear progression we have width. There’s just so much fucking shit out there to take from. The amount of stuff you can be influenced by is huge, and the result is that instead of moving forward, you can just say, “I’ll take some of this from over here, and that from over there.” That’s not a negative, it’s just that there’s a lot of flotsam to sift through.

The first three LCD albums formed such a perfect conceptual triangle. How does American Dream fit in with what came before?

It’s a completely new phase for the band. Everything from 2002 to 2011 is a thing, and now this is the beginning of another period. So there’s a big fucking moat of breaking the band up and coming back that helps clarify different eras. Also, it used to be that the only reason I could allow myself to make LCD Soundsystem records was that I’d be DJing and frustrated that there wasn’t more music that fit the needs of dancing but wasn’t “dance” music — so I made that music. But as I get older I’m more and more at home writing proper songs. There’s something more classic about that, which could be worse or better. For the moment, I like this record more than I like other records I’ve made.

What are you self-conscious about now that you wish you weren’t?

I mean, everything. What’s interesting for me about making this record is that the first LCD singles were just about allowing myself to make dance music. The first album was about letting myself try a couple of different types of music and call it an album without worrying about whether the whole thing cohered. Then Sound of Silver was me pushing myself to be a little stranger and make something cohesive. The third album was about trying to have a crazy rock-and-roll experience while making a record — renting a mansion and living like a crazy person with everyone dressing in white dashikis while we made it. The new album was about forcing myself through my discomfort with singing and not allowing myself to have much wry distance. So it’s all scary again. And I’m risking my whole comically earned legacy by making a new album in the first place. We had a fucking perfect finish and no matter how good American Dream is that legacy is thrown out.

The way you mentioned the Stooges and Little Creatures earlier suggests you’ve paid pretty close attention to the different narrative arcs of different bands’ careers. Are there any bands that broke up and then reformed that you’re looking to as either a model or a cautionary tale?

The bands I find most inspiring are cautionary tales. The Fall is a cautionary tale. Mark E. Smith is relentless, uncompromising, and some might say a prick.

But the Fall has never stopped.

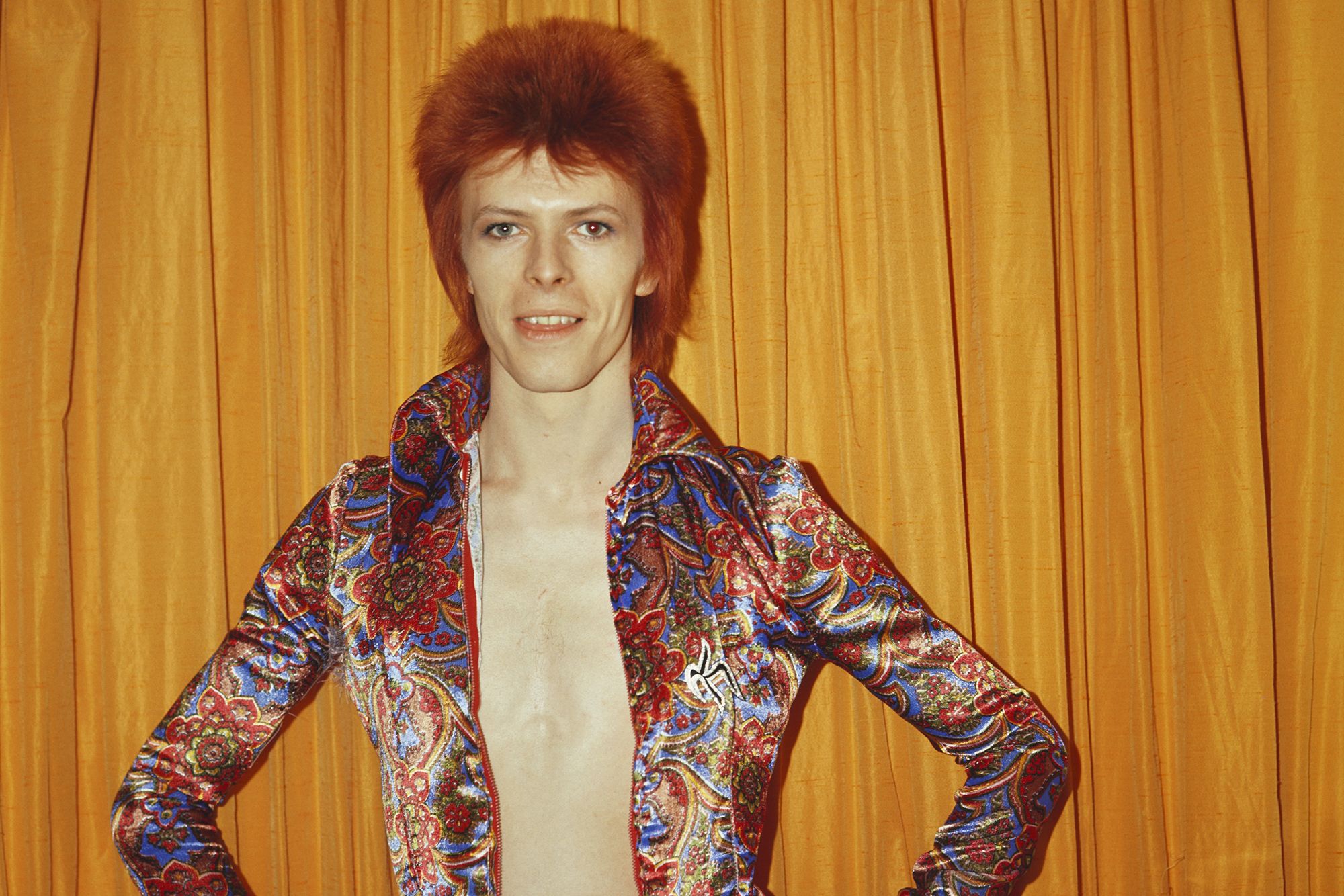

That’s true, they haven’t. I don’t know that there are a lot of people in our band’s circumstance. I don’t know if there’s anybody to look to except for maybe Bowie killing Ziggy Stardust or something. But I don’t blame any band that comes back. It’s a nice form of validity. You’d be pretty coldhearted not to come back at least once for people who really truly just want to hear you play.

The Smiths are the last reunion holdouts.

Yeah, but they didn’t come back because Mike Joyce sued Morrissey and Marr. I think if Mike Joyce had not sued them they would’ve come back. If there was no bad blood, it would’ve happened. But I don’t think Morrissey is capable of no bad blood

Bad blood is the blood with him.

That’s actually the name of his next solo record, Bad Blood Is the Blood.

How soon after saying LCD Soundsystem was done did you get offers to come back?

There were offers. There was one offer that I won’t get into out of respect for the people who made it, and it was largely made because there was a headlining spot at a festival that a band had bailed on and total last minute the promoters were like, fuck, fuck, fuck, fuck … hey, LCD Soundsystem we got a weird idea for you. I’ve always had an impish joy about saying no to things that are very lucrative.

What’s the most pleasure you’ve gotten from saying no?

There was an ad, and I won’t say who it was for — a corny clothing company — and they shot a whole video for us of people lip-syncing to one of our songs. I looked at it and almost threw up in my mouth. I said there’s no way they can use this song. They’re like, “Okay. We’ll double the offer.” “Yeah, you’re not hearing me. You can’t use this fucking song.” “Okay. We hear you loud and clear …We’ll double it again.” By breaking up my band, I’d left a lot more on the table than what they were offering. Did they think I was going to sacrifice all that for some shitty ad? So, yeah, it felt good to say no to that. It felt really good.

This interview, a version of which appears in New York’s 8/21 issue, has been edited and condensed from two conversations.

The magnetic front woman of the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Karen O also wrote the soundtrack to Spike Jonze’s Where the Wild Things Are and was nominated for an Oscar for “The Moon Song” from Jonze’s Her.

The magnetic front woman of the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Karen O also wrote the soundtrack to Spike Jonze’s Where the Wild Things Are and was nominated for an Oscar for “The Moon Song” from Jonze’s Her.

“America’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll Magazine” was known for its early adoption of punk and New Wave. Running from 1969 to 1989, the monthly fostered a generation of music writers, including Robert Christgau, Greil Marcus, Cameron Crowe, and Lester Bangs.

Born John Anthony Genzale Jr., Thunders was the guitarist for the proto-punk cross-dressers the New York Dolls, and founded the Heartbreakers with Richard Hell. He died of an overdose in New Orleans in 1991 at the age of 38.

Metallica played the MetLife Stadium, formerly known as Giants Stadium, on May 14, 2017.

Even before Murphy announced the band’s end, LCD’s “last” record was the darling of critics, dancers, and people who still bought music, sending This Is Happening to the top ten of the Billboard 200.

Talking Heads’ 1983 record Speaking in Tongues was their greatest commercial success and last front-to-back flawless effort. College radio stations generally don’t touch the stuff from 1985’s Little Creatures.

The April 2, 2011, “final show” at Madison Square Garden lasted almost four hours. When Murphy announced the band’s return four years later, some fans were less than thrilled: “I think if your band reunites less than 10 years after your advertised last show, you have to refund all the money from it,” tweeted Pitchfork writer Stuart Berman.

LCD Soundsystem’s first two nominations were at the 2006 Grammys, where they earned nods for Best Electronic/Dance Album and Best Dance Recording (“Daft Punk Is Playing at My House.”) In 2008, Sound of Silver was also nominated for Best Dance Recording.

In New York’s Where to Eat 2016, restaurant critic Adam Platt compared Murphy’s bar, the Four Horsemen, to “the café area of an upscale Nordic health club.” Its 17-page wine list provides “an education in the new generation of funky, drinkable, weirdly satisfying natural wines.”

In 2014, Murphy teamed up with Blue Bottle Coffee to release the one-off House of Good espresso — “a harmony between the voluptuous and the austere.”

“America’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll Magazine” was known for its early adoption of punk and New Wave. Running from 1969 to 1989, the monthly fostered a generation of music writers, including Robert Christgau, Greil Marcus, Cameron Crowe, and Lester Bangs.

Born John Anthony Genzale Jr., Thunders was the guitarist for the proto-punk cross-dressers the New York Dolls, and founded the Heartbreakers with Richard Hell. He died of an overdose in New Orleans in 1991 at the age of 38.

Metallica played the MetLife Stadium, formerly known as Giants Stadium, on May 14, 2017.

Even before Murphy announced the band’s end, LCD’s “last” record was the darling of critics, dancers, and people who still bought music, sending This Is Happening to the top ten of the Billboard 200.

Talking Heads’ 1983 record Speaking in Tongues was their greatest commercial success and last front-to-back flawless effort. College radio stations generally don’t touch the stuff from 1985’s Little Creatures.

The April 2, 2011, “final show” at Madison Square Garden lasted almost four hours. When Murphy announced the band’s return four years later, some fans were less than thrilled: “I think if your band reunites less than 10 years after your advertised last show, you have to refund all the money from it,” tweeted Pitchfork writer Stuart Berman.

LCD Soundsystem’s first two nominations were at the 2006 Grammys, where they earned nods for Best Electronic/Dance Album and Best Dance Recording (“Daft Punk Is Playing at My House.”) In 2008, Sound of Silver was also nominated for Best Dance Recording.

In New York’s Where to Eat 2016, restaurant critic Adam Platt compared Murphy’s bar, the Four Horsemen, to “the café area of an upscale Nordic health club.” Its 17-page wine list provides “an education in the new generation of funky, drinkable, weirdly satisfying natural wines.”

In 2014, Murphy teamed up with Blue Bottle Coffee to release the one-off House of Good espresso — “a harmony between the voluptuous and the austere.”

The Italian manual espresso machine that’s basic model starts in the four figures.

From the Newsweek online piece about the album’s cover: “If it was just a stock photo of a daytime sky, à la Window’s default wallpaper or a Sims game, that would be one thing. But there’s something about that particular shade of blue — GoGurt blue, dare I call it — and uninspired font layered on top that plunges this artwork into the depths of the Uncanny Valley.”

An especially harsh single from Michael Gira’s experimental and intensely loud band Swans.

The Italian manual espresso machine that’s basic model starts in the four figures.

From the Newsweek online piece about the album’s cover: “If it was just a stock photo of a daytime sky, à la Window’s default wallpaper or a Sims game, that would be one thing. But there’s something about that particular shade of blue — GoGurt blue, dare I call it — and uninspired font layered on top that plunges this artwork into the depths of the Uncanny Valley.”

An especially harsh single from Michael Gira’s experimental and intensely loud band Swans.

The eerie, minimal proto-punk of Alan Vega and Martin Rev was simultaneously among the more catchy and more disturbing outgrowths of the revered late-1970s New York punk scene.

A 2012 concert doc on the Madison Square Garden show that includes footage from the day before and after the show. The concert was also released in 2014 as a five-LP album, The Long Goodbye.

The eerie, minimal proto-punk of Alan Vega and Martin Rev was simultaneously among the more catchy and more disturbing outgrowths of the revered late-1970s New York punk scene.

A 2012 concert doc on the Madison Square Garden show that includes footage from the day before and after the show. The concert was also released in 2014 as a five-LP album, The Long Goodbye.

The eyelinered synth band from Sheffield, England, came from avant-garde pop roots to write the karaoke gem “Don’t You Want Me,” which topped the chart in the U.K. in 1981 and the U.S. in 1982.

Edwyn Collins fronted the Scottish band Orange Juice, who were to post-punk what the Memphis Group were to design: bright, squiggly, and captivating. They dried up in 1984, but a decade later, Collins nabbed a surprise hit with “A Girl Like You.”

In Autobiography, published in October 2013, Morrissey writes of life as a fan and as a singer in remarkably florid prose. It’s hard not to read passages like “The unhappy past descends upon me each time I hear their voices” in his singsong delivery.

Drummer Mike Joyce sued Morrissey and Johnny Marr for taking 40 percent of royalties each, leaving Joyce and bassist Andy Rourke to collect the change. In 1989, Joyce and Rourke sued Moz and Marr for an even split; Rourke quickly settled, but Joyce hung in until 1996, when the English high court awarded him £1 million in back royalties and 25 percent of future Smiths earnings.

Named after the nonsense syllables of a doo-wop hit, this ’70s nostalgia group churned out versions of ’50s rock and R&B.

Jay-Z reflects on race and wealth on this minimal track from his recently released, well-regarded album 4:44.

New Jersey sisters Maggie, Terre, and Suzzy Roche delivered gorgeous and, at times, gorgeously off-kilter harmonies and wry lyrics as a beloved, if never quite mainstream, folk trio.

Beginning with the English prog-rock staples King Crimson, the 71-year-old guitarist has had his hands on an outsize number of influential records, from Bowie’s Heroes to Brian Eno’s classic solo albums to the sounds of the Windows Vista OS. He’s a pioneer in adapting new technology, a drill sergeant of a bandmate, and you wouldn’t want to get caught taping his shows.

Led by the gruffly iconoclastic Mark E. Smith, the Fall debuted their fierce, rhythmically entrancing post-punk in Manchester in the late 1970s. They’re still at it.

The eyelinered synth band from Sheffield, England, came from avant-garde pop roots to write the karaoke gem “Don’t You Want Me,” which topped the chart in the U.K. in 1981 and the U.S. in 1982.

Edwyn Collins fronted the Scottish band Orange Juice, who were to post-punk what the Memphis Group were to design: bright, squiggly, and captivating. They dried up in 1984, but a decade later, Collins nabbed a surprise hit with “A Girl Like You.”

In Autobiography, published in October 2013, Morrissey writes of life as a fan and as a singer in remarkably florid prose. It’s hard not to read passages like “The unhappy past descends upon me each time I hear their voices” in his singsong delivery.

Drummer Mike Joyce sued Morrissey and Johnny Marr for taking 40 percent of royalties each, leaving Joyce and bassist Andy Rourke to collect the change. In 1989, Joyce and Rourke sued Moz and Marr for an even split; Rourke quickly settled, but Joyce hung in until 1996, when the English high court awarded him £1 million in back royalties and 25 percent of future Smiths earnings.

Named after the nonsense syllables of a doo-wop hit, this ’70s nostalgia group churned out versions of ’50s rock and R&B.

Jay-Z reflects on race and wealth on this minimal track from his recently released, well-regarded album 4:44.

New Jersey sisters Maggie, Terre, and Suzzy Roche delivered gorgeous and, at times, gorgeously off-kilter harmonies and wry lyrics as a beloved, if never quite mainstream, folk trio.

Beginning with the English prog-rock staples King Crimson, the 71-year-old guitarist has had his hands on an outsize number of influential records, from Bowie’s Heroes to Brian Eno’s classic solo albums to the sounds of the Windows Vista OS. He’s a pioneer in adapting new technology, a drill sergeant of a bandmate, and you wouldn’t want to get caught taping his shows.

Led by the gruffly iconoclastic Mark E. Smith, the Fall debuted their fierce, rhythmically entrancing post-punk in Manchester in the late 1970s. They’re still at it.

After his final performance as martian rock star Ziggy Stardust in July of 1973, David Bowie, as you may have heard, came back to Earth and released a large handful of classic music throughout the 1970s.

After his final performance as martian rock star Ziggy Stardust in July of 1973, David Bowie, as you may have heard, came back to Earth and released a large handful of classic music throughout the 1970s.