Once New York originated hip-hop in the ÔÇÖ70s, a further innovation followed swiftly on its heels: the rap crew was born. For all the vaunting of self for which the art form is rightfully known, the same rule holds in rap as in other creative fields: just because rap opened up new frontiers for out-and-out bragging didnÔÇÖt mean that its artists had lost the need for collaboration, collective promotion, and mutual protection. Rap crews were a crucial element of hip-hop culture ÔÇö whether crews were organically bonded or hitched together by a record label (or both), the notion of strength in numbers was impossible to miss. One needed both bars and bodies to succeed. The history of classic hip-hop is one centered on teamwork: more often than not, the artÔÇÖs foundations were laid by groups. Individual brilliance was vital to their success, but when hip-hop advances, it mostly advances in company: Sugarhill Gang, the Furious Five, Run-D.M.C., Juice Crew, Boogie Down Productions, Public Enemy, A Tribe Called Quest, and countless others.

The gangster-centered modern era cast a brighter spotlight on the individual star, but even those icons came with squads attached. In the New York area there was BiggieÔÇÖs Junior Mafia, PuffÔÇÖs Bad Boy crew, Jay-ZÔÇÖs Roc-a-Fella squad, the duo Mobb Deep and their affiliated Queensbridge artists, DMXÔÇÖs Ruff Ryders, 50 CentÔÇÖs G-Unit, Dipset, the Coke Boys. The exception that proved the rule was Nas, and even Nas wasnÔÇÖt much of an exception, joining up to form the unwieldy supergroup the Firm and engaging in frequent collaboration with the Queensbridge contingent as well as members of the Wu-Tang Clan. A nine-headed army housing multiple stars and tied to dozens of secondary affiliates, Wu-Tang set a lasting standard as the ultimate rap crew. The Clan showcased the benefits of group solidarity to an unprecedented degree: more intimidation, more personality, more cooperation, stronger competition, secure in-house production, in-house lingo, in-house fashion. And, as time went on, its drawbacks. Prolonged companionship could lead to friction and fractiousness, and the inevitable fact that some members thrived while others languished made for bigger egos on the one hand and greater jealousy on the other. Buffeted by centrifugal forces, the RZAÔÇÖs leadership became harder and harder to exert, and eventually the Clan disbanded in all but name.

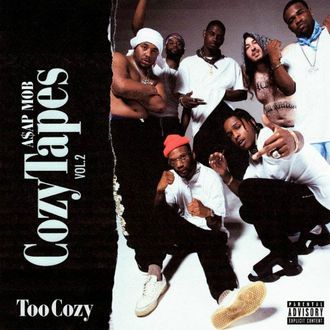

Of course, everyone still loves the Wu-Tang Clan, and nothing can keep rappers from hiving up in New York. Contemporary hip-hop in the city is often still written in the language of crews, and even super-crews: BrooklynÔÇÖs Pro Era, Flatbush Zombies, and the Underachievers have aligned together under the Beast Coast banner. But for the past few years, the cityÔÇÖs most prominent squad has been A$AP Mob, the Harlem-based collective organized by Steven Rodriguez, best known as Yams. Combining his great talents as a hip-hop historian, talent scout, and online publicist, YamsÔÇÖ vision and meticulous planning catapulted the MobÔÇÖs lead artist A$AP Rocky into stardom and a major-label deal in 2011. RockyÔÇÖs exuberant success was soon followed by that of A$AP Ferg in 2012 and 2013. All told, the Mob has kept a relatively low profile in the wake of YamsÔÇÖ untimely death, in January 2015. Rocky last dropped a solo album, the mournfully subdued At Long Last A$AP in 2015; Ferg dropped his own sophomore album last year, that, like the inaugural volume of the MobÔÇÖs Cozy Tapes album series (Friends), stirred up less conversation than its more capable performances deserved.

2017 marks a turning point. As his ace features on Lana Del ReyÔÇÖs Lust for Life proved, Rocky has leveled up lyrically while retaining the finesse and fashion sense that originally made his name. Atlanta native and recent A$AP signee Playboy Carti has come up driven by the force of his top-30 single ÔÇ£MagnoliaÔÇØ and a well-earned reputation for choice ad libs. August has been the most prolific month of all for the Mob as a whole, with A$AP Twelvyy launching his debut album 12 on the fourth, Ferg dropping his Still Striving mixtape on the 18th, capped off by the MobÔÇÖs Cozy Tapes, Vol. 2: Too Cozy last Friday. Whether in terms of mainstream currency with Rocky and Carti or in terms of appeal with hard-core hip-hop heads with Ferg and Twelvyy, the team is raising its profile. The time is ripe for explanations of what the group represents and where it stands regarding the long history of New York hip-hop.

If Rocky and Ferg have made names for themselves by stepping outside the limitations of the canonized New York sound, Twelvyy, the third man up, is dedicated to building a link with the past. 12 is clearly a collection that re-creates the time-tested boom-bap sound in TwelvyyÔÇÖs image (exemplified by the lead single ÔÇ£StrappedÔÇØ) instead of breaking from it. The production isnÔÇÖt dusty in the least, but it is familiar, and Twelvyy spends most of his time recounting his past life in well-sculpted verses. The interchangeable, impersonal one- and two-liners typical of contemporary trap, though not completely absent (witness the kinetic, Ferg-featuring ÔÇ£Hop OutÔÇØ), are in short supply. Twelvyy has a story worth telling, and he tells it well: an impoverished childhood in the BronxÔÇÖs Castle Hill salved by comic books and anim├® leads to a gun-toting adolescence (ÔÇ£Tetsuo [from Akira] with a Tommy gunÔÇØ; ÔÇ£Threw the Glock up in the river, it was too dramaticÔÇØ) that culminates in Mob induction and its attendant success and wealth. As an individual effort, 12ÔÇÖs a worthy debut: having made the most of having to wait his turn, TwelvyyÔÇÖs turned in a consistent, focused album that leaves him room to develop further, though RockyÔÇÖs feature on ÔÇ£DiamondsÔÇØ shows the gap between a full-fledged star and one still in formation.

As an A$AP Mob production 12 highlights the long-standing continuities between the Mob and the world beyond it. Such connections are ones that Ferg himself, in his burly and boisterous voice, is eager to reinforce on his own tape. ItÔÇÖs somewhat unfair to a collection as strong as Still Striving to reduce it to one song, but the remix of ÔÇ£East CoastÔÇØ is grand enough to stand in for the whole. FergÔÇÖs long been known for assembling constellations on his remixed hits, but ÔÇ£East CoastÔÇØ congregates with a higher purpose than mere networking in mind: the glittering rock-star stomp of the original beat is blessed with artists ranging from the distant past (Busta Rhymes, who just about steals the show at the start), to recent city elders (French Montana) to exact contemporaries (Rocky, Dave East), to regional guests (Rick Ross from the South, Snoop Dogg from the West). The song is at once a festival of boasting and an exercise in hospitality. FergÔÇÖs heavy yet bouncy tones have always played well with others, and one of the things Still Striving strives for is inclusion ÔÇö only three tracks out of fourteen have no features.

Meanwhile, Too Cozy, as an album credited to the Mob as a whole, is nothing if not one long posse cut: of the 14 non-skit tracks (the skits, two of which feature John C. Reilly as a chill high-school principal, are incidentally quite funny), more than half feature five or more performers. Lesser lights of the Mob (Nast, Ant, TyY) rub shoulders with visiting dignitaries (Chief Keef, Gucci Mane, Schoolboy Q, Big Sean, Quavo, Frank Ocean, Jaden Smith) over a collage of beats culled from a small army of producers, and everyone gets their chance to shine: Carti traipses on a golden hook on ÔÇ£Walk on WaterÔÇØ; Slade Da MonstaÔÇÖs churning, wicked beat on ÔÇ£BahamasÔÇØ takes precedence over the seven rappers on it; Nast rips open a chorus on ÔÇ£Feels So GoodÔÇØ; Twelvyy revisits his 12 cut ÔÇ£LYBB (Last Year Being Broke)ÔÇØ on Too CozyÔÇÖs ÔÇ£FYBR (First Year Being Rich)ÔÇØ to good effect.

The most notable track, though, is ÔÇ£What HappensÔÇØ: produced by the RZA himself, the grimy, punchy beat exudes a classic Wu-Tang vibe enhanced by the presence of a veritable convention of current New York rap groups: along with the MobÔÇÖs A-team of Rocky, Ferg, and Twelvyy thereÔÇÖs Pro EraÔÇÖs Joey Badass, Kirk Knight, Nyck Caution, and Flatbush ZombiesÔÇÖ Meechy Darko and Zombie Juice. Much as RockyÔÇÖs success allowed him to bring his crew up with him, the Mob is making use of its relative prominence to pull up the rest of New York: itÔÇÖs smart strategy that, if ÔÇ£What HappensÔÇØ is any indicator, has the potential to make for some excellent art. New York has lyrical talent and physical style in abundance. What holds it back currently is the absence of a distinctive school of production of its own on par with that of Atlanta or the West, which leaves it cherry-picking sounds from the rest of the country. Yet if the RZAÔÇÖs genius revives in full (a possibility borne out by the recent announcement of a new Wu-Tang album), that issue is all but resolved. ÔÇ£What HappensÔÇØ holds out the possibility that the future of New York rap may well be posse-centered to a degree unheard of since the ÔÇÖ80s.

Of course, even crews in the ÔÇÖ80s were centered on stars, and the Mob is no different. RockyÔÇÖs presence on the three August collections is quiet but still forceful. ItÔÇÖs clearly leading up to another album which, as announced on ÔÇ£Diamonds,ÔÇØ is due around holiday season. He remains the figurehead of the group; and, since YamsÔÇÖ death, seems to have grown into its captain.┬áWhether itÔÇÖs building bridges with high fashion or cutting ties (some, but not all) with Mob co-founder A$AP Bari over his recent sexual-assault scandal, Rocky leads the way for the Mob. His relaxed demeanor exemplifies the state of a crew that, benefiting from a vast cultural heritage, can afford to strive in style and peace. And novelty as well. If, since the ÔÇÖ90s of East Coast boom-bap and West Coast G-funk, the best rap where substance dictates style has migrated west to Kendrick LamarÔÇÖs Los Angeles, one can argue that the best rap where style is a substance all its own has traveled east to A$AP MobÔÇÖs New York.