Robert Pattinson looks, in person, unmistakably like Robert Pattinson — which is to say, as he does in films and in most photographs. He’s been endlessly photographed for his inescapable talent for looking like, well, Robert Pattinson. His mother was a model booker, and he started modeling early and has more recently been the face of Dior. This is also his burden, if you want to call it that, his handsomeness weaponized by his years playing Twilight’s perfect vampire boyfriend, Edward Cullen, a role that might as well have been specially designed to condition impressionable young filmgoers into an incurable Pavlovian hormonal swoon, forever. A few years back, he had to sell his big house near Griffith Park because it became too infested with paparazzi — he’d even dress his assistant up as Robert Pattinson and send him out as a decoy in his car.

It’s not that he hasn’t proved that he can act, and, to his credit, he’s sought out parts in non-pop films, from the Ur-finance bro in Cosmopolis to the thoughtfully bewhiskered Edwardian explorer in The Lost City of Z — but his roles tend to also require him to look like some version of himself.

The Safdie brothers, Josh, 33, and Benny, 31, managed to get something else out of him in their new film, Good Time. Pattinson approached the brothers in 2015 after coming upon a still online from their last film, Heaven Knows What, starring Arielle Holmes, a former street junkie, and based on her personal experiences, thinking: That seems not-very-Twilight-like. The Safdies, it turns out, make their films in a hell-bent, intuitive, collaborative way, often using friends or people they’ve just met as the actors and sometimes avoiding the usual niceties such as filming permits. All that appealed to Pattinson, who also, for what it’s worth, doesn’t need the big Hollywood paycheck.

It’s part of a larger project, or experiment, for Pattinson, now 31, to redefine his career, and himself, to use his supernatural fame for something good — or interesting to him, anyway. “What he wanted,” says Benny, “was, as he said, to disappear into something, to make something where he is not himself. And we thought: Let’s take him at his word.”

And so they made Good Time, a kind of bleak caper film, which opens August 11 and stars Pattinson as Connie Nikas, a feckless young scumbag who decides to recruit his mentally challenged brother, Nick Nikas — played with sweet-faced Of Mice and Men rage by Benny — into committing a bank robbery with him. Things don’t go well, and as the movie careers around the less-cinematic reaches of Queens, they continue to spiral downward. Its grit and restless vigor evoke movies like Dog Day Afternoon, Kids, and Sid & Nancy, totems of insouciant retro-cool, but scored with calamitous, portentous synth music by Daniel Lopatin. It was, for Pattinson, also a kind of escape — an artistic slumming — that did allow him something almost magical: In costume, in character, he was able to take the subway unmolested.

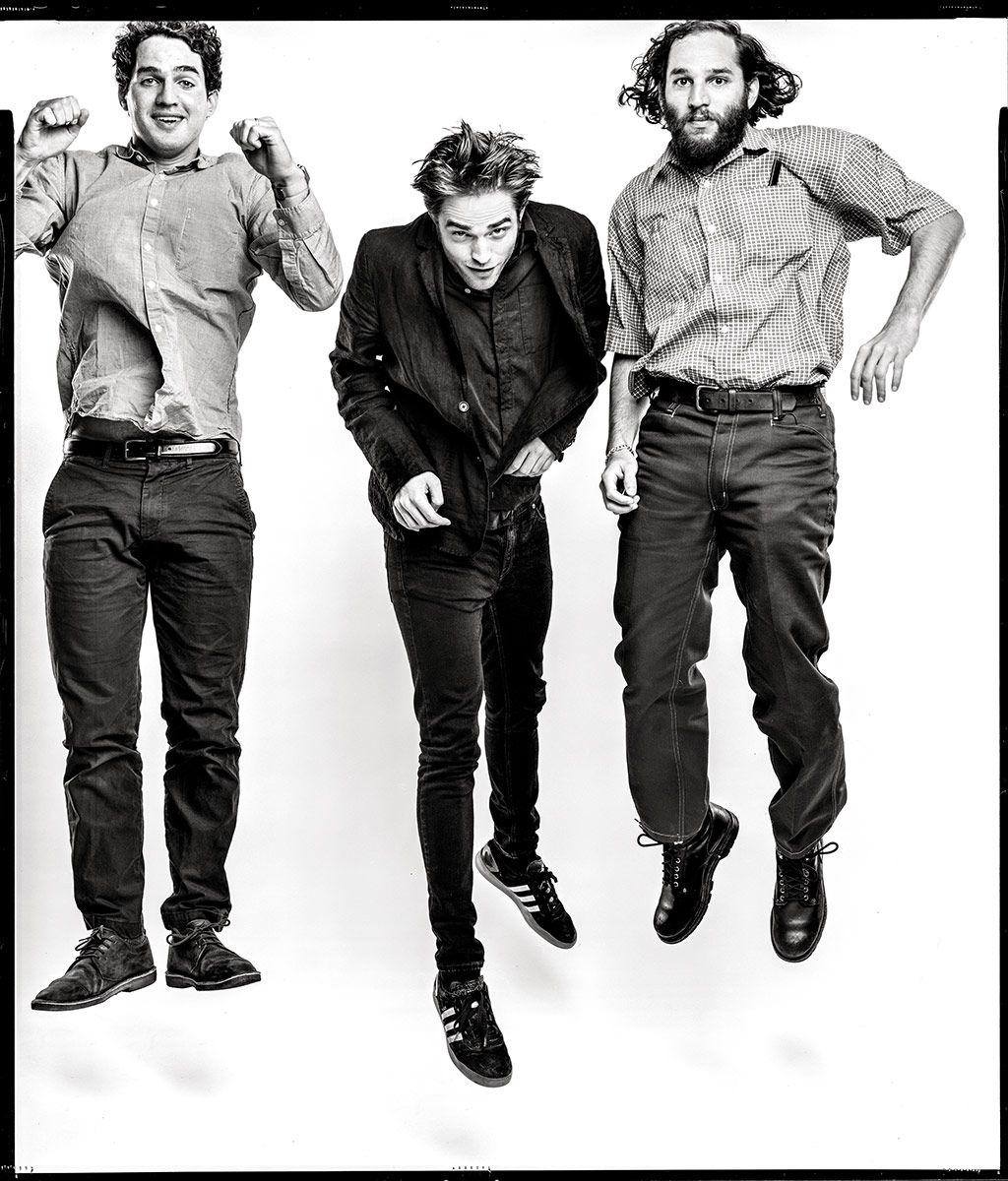

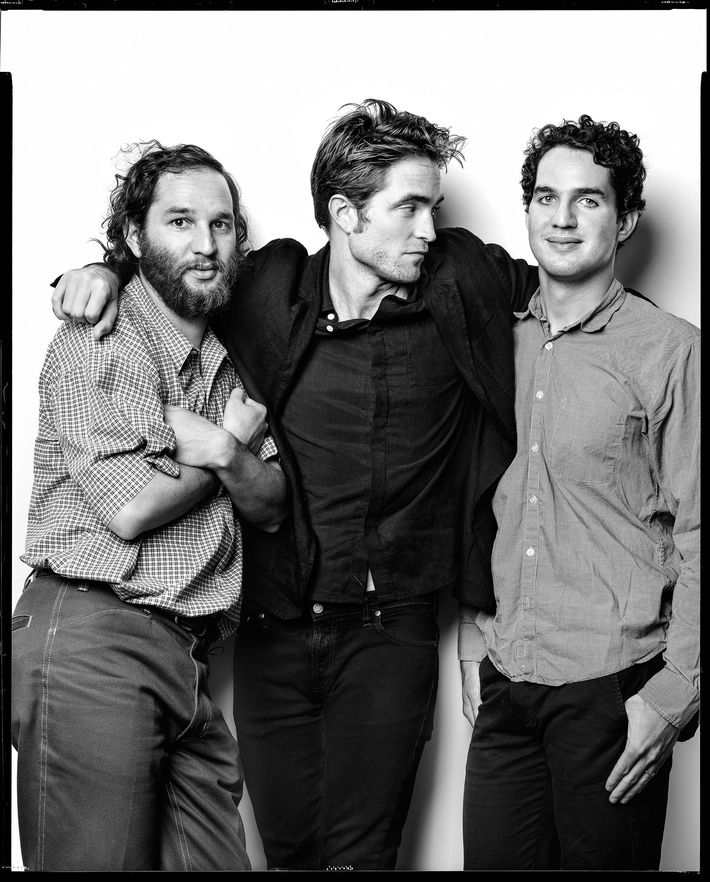

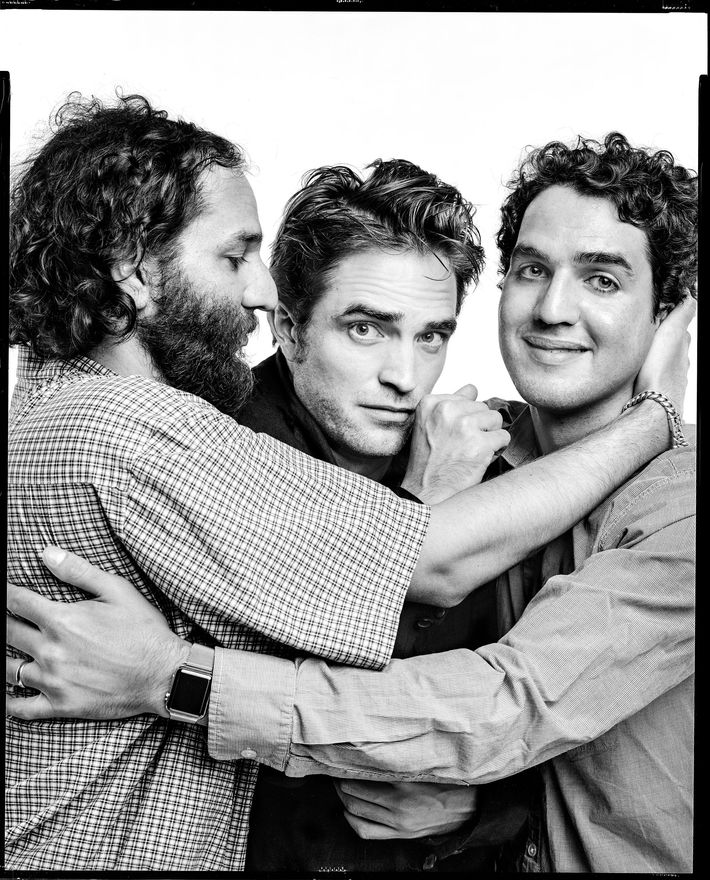

Pattinson and the Safdie brothers met up with me on the roof deck of Spring Studios, where we drank iced coffee and nibbled on some pastries while Pattinson discreetly vaped.

There’s a legend of how you got involved with the Safdies. Did you know their work at all when you reached out to them?

Robert Pattinson: No.

Josh Safdie: That’s what’s so amazing. He just saw this still.

RP: It was on the banner of some website, just of Arielle’s face; she just has an amazing expression on her face. I liked the sensibility of it.

Is she super-fucked up on heroin? She has such a great high-as-hell face in that film.

JS: She’s actually not. It’s a still from a scene before she gets high.

Had you two ever seen Twilight?

JS: No, I still haven’t. I had seen Cosmopolis and The Rover when I met him …

Benny Safdie: Me either. When we met Rob, we were meeting Rob.

How did that first meeting go?

RP: I feel like it was just kind of agreed that we would do something. It wasn’t about any particular project or anything. But I remember leaving the meeting and thinking: Yeah. Usually a meeting about a movie is just with the director. And you’re kind of trying to impress them and they’re trying to impress you.

Like a date.

RP: So to have it with two people, it was more like entering a show.

They’re like a comedy routine.

RP: And that’s kind of what I wanted. I knew that to get to a certain level of energy that I wanted, you have to commit to somebody else’s world. And it seemed like they had a self-contained world that they were a part of, that they weren’t just trying to make a movie or whatever. But it felt like an entire environment you could go into. Because I have fallen into acting and have tried to become better, always I would go off what the other actor was doing, and trying to figure out how to be on the front foot instead of the back foot, and I could feel that with them, it was impossible to not be forced to be propulsive.

JS: That’s our whole thing, even with each other, is to blind each other with enthusiasm so that you have no other choice to be submissive to it, and that’s the goal of life — just to get lost, always.

What was your reaction to Robert’s contacting you?

JS: There is a real allure around Rob, and it was clear that he was interested in expressing himself and wasn’t making commercial choices.

I believe the word you used once was “weird.”

RP: I can think of a better one.

So you decided to make this film centered on him?

JS: Rob had a hole in his schedule, and we thought, Let’s make a piece of pulp, you know? I was reading The Executioner’s Song for the first time. I was reading In the Belly of the Beast [a book based on letters to Norman Mailer from a convict named Jack Abbott, whom Mailer helped get paroled and who shortly after killed a man].

So you thought, Let’s make him a criminal.

JS: I’ll say one last thing about Rob and his face. Glenn O’Brien, may he rest in peace, wrote this awesome piece years ago about how the American criminal had a very specific look to him. And it’s a look which has since been co-opted by the fashion industry — this idea of the criminal as uniquely good-looking, with a charm they used to their benefit …

BS: Like Ted Bundy …

JS: Charles Manson, Richard Ramirez. And we’re not going to sit here and pretend he’s not a good-looking guy; he’s uniquely good-looking. Sometimes you look like an alien.

RP: [Laughs] I’ll take it.

And what was the process like?

JS: While he was filming The Lost City of Z, we were talking a lot, building the character.

BS: He’d email me as Connie, and I’d respond as Nick.

RP: That was one of the most pleasurable things about this. A lot of people are so cagey about showing the new draft of the script or it never comes till it’s almost too late. And the next time it’s entirely rewritten. It’s nice to see the process. It makes you much more invested in the project.

How did it evolve?

JS: The really early iteration of it was a prison movie where he breaks free.

BS: And so that was one of the things we started from. And then the energy of Rob — he’s almost on the run all the time. He’s constantly trying to avoid kind of being seen all the time. I remember very specifically location scouting with Rob. Because we do that with the talent, it brings a lot, even if the space isn’t used. I remember being at an off-the-beaten-path place, people started taking pictures and I saw it on his face, he went into almost war mode in his mind …

JS: And then everybody started gravitating over and pulled out their phones. But when we make the movie, we put a totally different energy out into the world, and nobody is paying attention, and we’re able to do whatever we want, wherever we want. It’s unbelievable.

RP: It is crazy how that works. To be completely invisible, and there’s a whole film crew and no one notices at all. It’s so strange.

BS: It’s all about distraction. At one point, we were in this very crowded street and we didn’t want Rob to get recognized. It was outside the Flushing Mall. And I have blood all over me, so everyone is staring at me — Oh, he has blood all over him! — it’s a perfect distraction.

RP: I was watching him too. I became part of the crowd.

So during the filming you did more walking around the city than you have in years?

RP: Way more, and way more brazenly. Part of it is that if you look really dirty—

You did look really dirty. Your skin was greasy.

RP: That was the main thing. When we realized the pockmarked thing …

BS: That was part of the character development.

RP: Literally, that was almost an immediate transformation.

JS: Tommy Lee Jones was a big inspiration. Because he played Gary Gilmore. And he has that skin.

BS: It says so much about someone.

Well, his diet anyway. You looked like you were toxic. Did you change what you ate for the film? [They all giggle.]

RP: I ate nothing but tuna. Out of little cans. I have this unhealthy thing where when I’m trying to lose weight I only eat tuna. And at the same time, I thought, It’s kind of healthy, I’ll eat tuna.

BS: Maybe you got mercury poisoning.

JS: It was pretty great. He stayed in a basement apartment a few blocks from my house and I remember going over to his place and it was just like a bombshell had gone off.

RP: [Giggles] I didn’t let anybody visit me. And I didn’t take the trash out. So the entire place just smelled like rotting fish. Filth everywhere.

This is how you normally live?

RP: If I am left to my own devices.

So part of what you liked about making this was being able to not be you, even in plain sight?

RP: The last time I shot in New York, it was, like, insanity. That was my expectation.

When was that?

RP: Remember Me, ages ago. But whenever I’ve been in New York, it’s been the same thing: You get spotted once, and literally you won’t be left alone afterward. And if I’m trying to do something, it’s a prison of self-consciousness. I thought that not only would that ruin my performance in this movie, it would ruin the whole movie.

Being unrecognized these days is an utterly unfamiliar experience for you.

RP: Yes, and as it went on, I realized there were ways to be invisible. Ways to behave. It was really interesting. And it’s what the character is doing also.

What do you think of Connie? I didn’t find him so sympathetic.

RP: But he does have purpose. I like the idea of a character who by all conventional expectations is a bad person. But it’s just impossible to just be a bad person.

Mailer had a certain romantic idea of the outlaw as being pure.

RP: He’s a guy who establishes his morality at will as he goes along. But at every moment when it changes, he’s completely convinced of it. Every time that he lies, he has no conception that he’s lying, at all; he’s never lying. If he’s believing something, it’s true.

So much of this is drawn from life. Buddy Duress, who plays another, even more hapless ex-con in the film, is a real-life friend of Josh’s who was in jail, and he helped inspire the script with his notes. You brought Pattinson to halfway houses and jails to get him in character.

RP: Josh would call up and say, “All right, we’re going on a tour of the Manhattan Detention Center.”

JS: He went in character.

RP: One of the guys asked me: So what are you here for, Scared Straight?

*This article appears in the August 7, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.