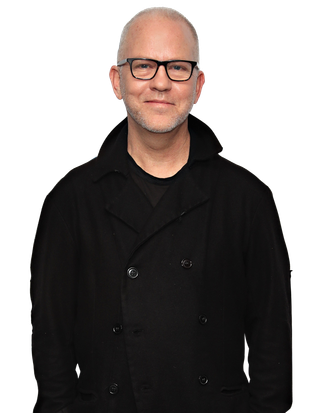

It seems that for every victory in the fight for gender equity in Hollywood (Patty Jenkins’s just-inked, history-making deal to direct the follow-up to Wonder Woman) there is a head-scratching downer (the void of female protagonists in CBS’s slate of new fall series). Ryan Murphy can call his campaign for gender parity for directors as a strong example of the former: Less than one year after launching his Half Foundation, the prolific series creator and executive producer (Feud, American Horror Story, American Crime Story, Scream Queens) has seen his company’s slate of female directors jump by 60 percent. Murphy, whose limited-series contender, Feud, earned 18 Emmy nominations, including for its leads Jessica Lange and Susan Sarandon, spoke to Vulture about why the business has failed women for so long, how his foundation can serve as a template for any company, and his personal crusade to ensure that networks are hiring a wide range of talent for the upcoming pilot season.

You’ve always made it a priority to showcase diverse talent in front of the camera, from special-needs performers to older actors. When did it hit you that you had to take on the cause of director diversity?

It really was an Oprah “a-ha” moment. On The People v. O.J. Simpson, I’d said from the beginning that because the “Marcia, Marcia, Marcia” episode was Sarah Paulson’s showcase, a woman should direct it. We had someone booked, but two weeks before filming, she bowed out because of an emergency surgery. We hemmed and hawed over who else was available and I said, “Forget it, I’ll do it.” Sarah is comfortable with me, and I understood the feelings in the script even though I’m not a woman. So I finished it, and it was good, but I felt really shitty: How is it that I didn’t have five or six great women directors on speed dial? I realized I was part of the problem. I looked at my company and we were exactly at the industry average: Only 15 percent of the director slots went to women. I felt really ashamed because I remember in 1999 when I directed my first episode of TV, I walked onto the set and I was the only gay person there.

This was on Popular.

Yeah, Popular. I had to beg and fight to direct that episode — even though it was my own show! I remember feeling oppressed, like a stranger in a strange land. I knew that feeling, so why am I not doing better? I looked at all the workshop and mentoring programs out there, and they were worthwhile, but the problem in the business was very simple: Somebody had to quantify power and responsibility. I had been saying, “I’ll do better, I’ll try harder,” but I hadn’t because I didn’t have the structure. So that’s how I came up with the Half Foundation: We would enforce that 50 percent of all the directorial slots be filled by women. Our country is now more than 50 percent women, and 57 percent of all entertainment is consumed is women. They are the majority on this front.

You’re actually making this process sound relatively simple. What was your first step?

It was. I called my boss, Dana Walden— who has two young daughters— and within 15 seconds she said, “Let’s do it. Let’s work harder so that all showrunners at Fox have a network of women they can draw from.” I’d never had a mentor in Hollywood. Men have always been control of the business and they usually mentor people who are like them, but two inches shorter. [Laughs.] So we’ve also created a mentorship program that’s like a directing boot camp during which people can also spend time in editing and in post — things you also need to know before you direct. We also pay women two weeks’ worth of their salaries to trail us; we don’t expect them to work for free. We saw that a lot of the women who were applying were working mothers, so we made a room available for those who were breastfeeding. Just because you have a baby on your hip or one on the way, or two at home, doesn’t mean you can’t go after your dreams.

One thing I don’t think a lot of us want to acknowledge is that women have also been complicit in this problem. The idea of, “No one helped me coming up; why would I train someone who may take my job someday?”

That’s always been in the water in Hollywood. I wrote about it in Feud! The business is obviously controlled by men, so within that system, there’s room for only one woman to succeed, which is the idea of the “It” girl in our culture. There’s no “It” boy! And the “It” girl concept applies to every area of Hollywood; basically, “You are the chosen one.” So what happens is, all of the women who want to be successful and economically viable are operating in a culture where they have to fight for that one position, and then comes the Betty versus Joan backstabbing. But if you walk into a business where 50 percent of the positions are held by women, I think that instinct goes away. It becomes a more nurturing, loving, safe space. I hear it from women all the time. “Only one of us gets chosen, so it’s human nature to fight for that job.” But men have never had to do that — ever.

What direct impact have you seen gender equity have on your shows? For example, I’ve heard from many actors — male and female — that they prefer a female-heavy set because there is less ego and more empathy.

To be blunt, the work has been better. And you’re right — there is more empathy, patience, and a safe space for the talent. I remember I always felt much more safe standing up on a chair and singing in front of my mother than I was in front of my father! I can also say our work has been deeper. It’s interesting when you look at Jessica’s and Susan’s careers; for the most part, they’ve been directed by men. But in Feud, four of the eight episodes were directed by women. I think they both felt so liberated and safe in their emotional choices because the person guiding them had been through some of these issues — especially ageism. That was cool to watch.

It seems like it’s become increasingly stupefying for executives to — for lack of a better word — figure how to “prioritize” their diversity initiatives. A few years ago, when Empire became a giant hit for Fox, suddenly there was a mad dash to hire black writers. Now the business is scrambling to address the women problem, alongside broader inclusion of LGBTQ talent as well.

It’s interesting — even though our foundation was created to give 50 percent of directing slots to women, 90 percent of everybody who’s directed over the last year have been minorities. That happened because we adopted a general philosophy of: “Let’s create a world where everyone has a voice.” For example, pilot season is coming up, and I’m going to have a meeting with every broadcast head and say, “Here are ten women and the five people of color who have proven to be great directors. I vouch for them. Hire them. Make it a part of your business model.” The other thing that’s bullshit is when you hear powerful people say, “We don’t know where to find the women — they’re all booked.” That is an abject lie. Just admit that the system is broken; here’s how we can fix it, and boom — you have a hiring rule. I’m really looking forward to those meetings with the network heads.

So you’re almost functioning as an agent now.

[Laughs.] I do feel like their agent and their manager because I want to be their advocate, and I know what it’s like not to have an advocate and how much harder you have to work because of it.

Did you have anything to do with Jennifer Salke and Bob Greenblatt’s recently announced initiative to train and hire female directors at NBC? I actually felt like the announcement was rather tone-deaf by the implication that there is “a drought of female directors” in Hollywood, which you’ve just explained is not the case.

Jennifer is a friend of mine and I don’t think that she meant that word “drought” specifically. I do think that you’re right that that idea has been an excuse — corporately — for a long time. But yes, there are 300 women available right now who’ve gone to film school and done the work. They’ve done everything a man has done, so why are the men with those same qualifications getting hired first?

There are so many filmmakers who, say, have success with their indies at Sundance, and then wait years and years into their 30s and 40s — which is such a crucial time in anyone’s career — to get hired again, and then suddenly they are 50 and feel as if they’ve missed their window.

That’s exactly right. What I’m looking to do is turn the TV world into that indie landscape. “Okay an episode of American Horror Story can be your independent film. Here’s your calling card.” You don’t have to go around with your hat out for three years trying to raise money! Everything is set up for you. If you look at American Horror Story or Crime Story, these are visceral, action-packed, sometimes bloody episodes of television. They’re not “feminine.” They’re not about sexy women sitting around looking beautiful, drinking lattes. These episodes are calling cards to show companies like Marvel, “Look, women can do these kind of movies.”

How much are agents to blame for allowing gender inequity to fester for as long as it has?

I’m sure many agents have thought, “I’m not going to be able to monetize this client, so why put all my time and energy into a someone who’s never going to get hired?” What I’ve found is that the women who have volunteered for our foundation don’t even have agents. They can’t break through that system. You’re only going to get an agent if you have a couple episodes under your belt. So basically what we do is almost a “farm-to-table” approach; they call our hotline or send us an email, our people meet with them and we hire them. Once you get your foot in the door, we’ll try and help you get a great agent.

You became a parent nearly five years ago. How has becoming a father impacted your perspective on all of this?

Yes, I have two young children — 2-and-a-half, and 4-and-a-half — and when I started bringing them to set, I noticed there were a lot of white, straight men walking around. They are children of a gay man, and they’re coming to a set that’s dominated by straight men? What am I doing? I wanted to create a culture that allowed my children to see the world differently. If only from a strictly visual perspective, to have a child see a room where half of the people are women and minorities is so powerful. I think everyone wants for their children a world that’s better than the one they came up in.

You’re creating, to borrow a phrase from your NBC comedy, “a new normal.”

Yeah, and maybe that’s the victory? I hope that I never have to have a conversation with the boys where I have to say, “Women have power. And women can be the boss.”

This interview has been edited and condensed.