David Lynch is an American artist: a common statement, and one commonly applied to many. Where he seems to stands alone, on a national level, is in the scope of his vision. He isn’t just an American artist, but an artist of its disparate regions. Lynch’s revival of Twin Peaks, which devotes ample time to Las Vegas and New Mexico, completes a knight’s tour in his works of the six zones, differing wildly in terms of landscape, atmosphere, and population, that comprise the continental United States. Twin Peaks: The Return’s rendition of the southwestern desert and the casino mecca at its core takes place in correspondence with the investigation in Twin Peaks, situated at the northeastern corner of Washington. As nearby scenes in Montana suggest, the town, though nominally part of the Pacific Northwest, belongs to a mountain West defined by vast forests and mountain ranges rather than proximity to the sea.

Something common throughout his oeuvre: In keeping with the limitless insularity of the United States, there are no shores in Lynch’s work. His oceans exist in the psyche, not in reality. It’s telling that, in the course of three entire films set in Southern California, the Pacific beach never appears. Inland Empire is as far from Malibu or Long Beach as it is from conventional narrative; Mulholland Drive, though easier to parse, is equally dry. The windswept shack in the sands where a crucial reversal takes place in Lost Highway could pass for a coastal construction, but isn’t. Seeing the actual sea would apparently amount to an impossible awakening; Lynch’s works are sites where dreams, reaching their limits, fold back upon themselves and deepen. A saner nation, coming to the end of seemingly limitless westward expansion, might come to terms with a reality superior to its fantasies, but Lynch is never so American as in his intuition that there is no higher reality than dreaming itself. As anyone who’s experienced the delusional aura of Los Angeles knows, few travelers ever waken upon arriving at the frontier’s end. Instead, they enter into movies and television, which, spilling back across the country, ensure that their dream will go on forever.

As far as the Atlantic shore goes, it’s entirely absent as well. But the Northeast was as crucial for birthing Lynch’s cinematic dreamscapes as it was for forging the American Dream itself. Nearly two centuries after hosting the signing of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitutional Convention, Philadelphia would set an indelible mark on Lynch, an aspiring painter studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts who soon carried his taste for expressionist imagery into filmmaking. Though shot in California, Eraserhead, Lynch’s first feature film, is set in a metropolis directly based on the City of Brotherly Love as Lynch experienced it: a dark, wretched urban environment profoundly hostile to organic growth and rhythm. Reiterated by the brief, horrendous Manhattan scenes early on in Twin Peaks: The Return, Lynch distills the Northeast into its great cities, zones where a claustrophobic environment of stone, industry, and metal withers and eclipses the nature of forests, mountains, and open sky. Isolation, and the horror of isolation, prevails: From Eraserhead’s Henry staring into his cheap old radiator to Twin Peaks: The Return’s watcher of the expensive glass cube, the true purpose of a straight man in the East is to sit beside a stunted tree and gaze blankly into an enclosed space until something happens. Doing anything else, touching a woman especially, is a violation of the terms of use with dire consequences: the emergence of an amorphous other and graphic mutilation are sure to follow.

After that, who wouldn’t want to head West? If Lynch’s visions of the western American regions flow into each other, his regions to the East are far more distinct. Between the metropolis of the East and the Great Plains there is no connection: No two films of Lynch are as different as Eraserhead and The Straight Story, Lynch’s G-rated masterpiece from 1999 based on the true story of Alvin Straight, an old man in Laurens, Iowa, who drove a lawnmower several hundred miles to make peace with his estranged brother in Wisconsin. The Straight Story is uniquely temperate, sober, flat. Just as the uneven sounds and textures of the urban inferno give rise to deformed bodies and disturbed minds, the open plains make for plainspoken, kind characters with nothing to hide. Though the deformations, tragedies, and traumas typical of Lynch intervene — Straight, a Western Front sniper in World War II and recovering alcoholic, is still dealing with his accidental killing of a comrade — the characters in The Straight Story are ultimately defined by their ability to face up to their losses without distortion. Sufficient to reality, to limitations, they have no dreams or nightmares: They are themselves and no other. There is the possibility, rare in Lynch’s work, of making a distinction between his characters’ souls and the crimes that weigh upon them.

In this sense, Straight isn’t entirely alone. Wild at Heart, Lynch’s 1990 twisted road-trip comedy, begins with Nicolas Cage’s Sailor committing a murder (in self-defense) and ends shortly after his release from prison. And it’s arguable that Jeffrey Beaumont, Kyle MacLachlan’s protagonist in Lynch’s 1986 breakout Blue Velvet, atones for indulging his darker impulses by killing Frank Booth, the psychotic drug dealer, kidnapper, murderer, and rapist played by Dennis Hopper, who reveals them to him. These two films, Lynch’s least-substantial and best-known work respectively, are also notable for being his only two films set in the American South. Wild at Heart’s westward itinerary takes its lovers from Cape Fear, North Carolina, through New Orleans and into the fictional desert town of Big Tuna, Texas; Blue Velvet, shot in Wilmington, North Carolina, is set in Lumberton (an actual, nonfictional city) in the same state.

Given that Lynch’s non-southern works testify to a firm belief that environment and personal character reflect each other, it’s tempting to ask what is distinctly southern about these films beyond their mailing address; also tempting, given the distinct history (and mythos) of the South, to wonder what someone so in tune with the collective unconscious might have to say about it. Despite spending part of his adolescence in pre–civil rights North Carolina and Virginia, Lynch isn’t generally held up as an artist with southern sensitivities. How much did he, generally recognized as an artist of Americana and its extremities, understand about the nation’s most extreme region, a region where his surname bears a sense more horrible than any scene he’s ever filmed? In other words, what does David Lynch, one of the most (if not the most) important artist white America’s produced in the postwar era, have to say about race?

One possible answer is, well, nothing. “Lynch’s movies are essentially apolitical,” wrote David Foster Wallace in an ambitious essay for Premiere magazine tied to Lost Highway’s 1997 release. As often happened with a born professor, Wallace was responding to a question he himself had posed; the question in this case was “Why are Lynch’s movies all so white?” As often happened with his fictional characters, Wallace, despite being hopelessly deluded about his own objectivity, managed to inadvertently say something revealing.

Lynch’s films are in no way about ethnic or cultural or political tensions. The films are all about tensions, but these tensions are always in and between individuals. There are, in Lynch’s films, no real groups or associations. There are sometimes alliances, but these are alliances based on shared obsessions. Lynch’s characters are essentially alone (Alone): they’re alienated from pretty much everything except the particular obsessions they’ve developed to help ease their alienation (… or is their alienation in fact a consequence of their obsessions? and does Lynch really hold an obsession or fantasy or fetish to be any kind of true anodyne for human alienation? does the average fetishist have any kind of actual relationship with the fetish?) Anyway, this kind of stuff is Lynch’s movies’ only real politics, viz. the primal politics of Self/Exterior and Id/Object. It’s a politics all about religions, darknesses, but for Lynch these have nothing to do with testaments or skin.

When an artist writes at length about another artist, an element of self-portraiture tends to creep in, and Wallace on Lynch is no exception. Whatever its accuracy regarding Lynch himself, the reading of an artist too deeply focused on philosophy and depth psychology to meaningfully reflect on collective history is a deft summation of Wallace’s own vision of a world, and art, where the head-on collision of capitalist economics and entertainment culture had annihilated all social ties. Wallace was writing near the conclusion of a three-way cultural tug-of-war between Evangelical reactionaries, mainstream corporate media, and women and people of color demanding more representation that raged during the ’80s and early ’90s. In a typically Gen-X fashion, he engaged the question of race in art just long enough to dismiss it as irrelevant, and by the time it became possible to raise an eyebrow about equating homogenous whiteness in visual media with an absence of politics, Wallace, dead and beatified, was no longer around to interrogate.

It’s strange, though, how films introduced at the top of his paragraph as “essentially apolitical” end up having a “primal politics” by the end. And Lynch’s filmic “darknesses,” real, moral, and symbolic, which according to Wallace have no relation to race, are harder to separate from the manner in which power is organized outside the movie theater than Wallace imagined. Cinema is a world where the flesh becomes image and force. It is a world whose figures, whatever else they may be, have to be who they appear to be, and in this it cannot help but reflect upon a hierarchy where one’s position is tethered to one’s skin color. All of Lynch’s main characters are white: As far as American directors go, this is unexceptional, and it may well be the most normal thing about him. What is abnormal about Lynch’s films is the way he makes whiteness speak and turn its gaze upon itself. Very often, the crises that force his pale-faced leads to reveal their true nature are subtly and indelibly linked to the violence and discrimination that created and sustains their power, or in other words, whiteness.

Best to begin in the South: Wild at Heart is Lynch’s least accomplished film in no small part because it deals with race in too facile and direct a manner. That’s not its only flaw: With its constant leaps back in memory, it has the feel of an extended short cut that Family Guy would later introduce to a broader audience. Briskness and slickness sap the narrative and lower its stakes. So if viewers failed to note the importance of the film’s first scene, where Sailor, played by Nicolas Cage, enraged by a black man’s threat to kill him and have sex with his girlfriend Lula (Laura Dern), grabs that man’s head with both hands and smashes it into the floor until brains leak out, it wasn’t entirely their fault. As Bob Ray Lemon, the soon-to-be murder victim, informs Sailor before his ill-fated murder attempt, he was paid by Lula’s mother Marietta, a white woman, to kill Sailor.

The characters and their motives aren’t hidden so much as confused. Bob Ray Lemon is just the first member of a racial minority summoned by Marietta to take care of Sailor: Once Sailor breaks parole and flees with Lula toward California, she engages her ex-lover, the Hispanic crime lord Marcello Santos, to have him killed. Santos’s sinister organization of killers includes Juana Durango, a Hispanic woman (played by Twin Peaks’ Sarah Palmer actress Grace Zabriskie), her black lover Reggie, and Bobby Peru, a former Vietnam vet who, catching up to the cash-starved Sailor and Lula in Texas, convinces Sailor to help him commit an armed robbery. Arrested and sentenced again, Sailor parts ways with Lula and their young child upon his release: He’s not good enough for them, he says. Shortly after leaving Lula’s car, he is accosted by a rainbow coalition of street toughs: Asian, Hispanic, and black. He calls them faggots and they beat him up, upon which he experiences a visitation from Glinda, the Good Witch of the North (played by Twin Peaks’ Laura Palmer actress Sheryl Lee); “Don’t give up on love,” she tells him. Upon coming to, Sailor apologizes to the gang for calling them homosexuals and races off to catch up with Lula and their son, whose car has fortuitously been caught in a traffic jam. (Meanwhile Marietta, like the Wicked Witch of the West, has melted away.) The moral of the movie is somewhat muddled and highly cartoonish, but it carries a distinct racial charge. Inflicting violence on people of color, even when they’re sent to kill you, is bad; besides, the real enemy is a jealous old white witch who can only be defeated by embracing love.

Blue Velvet isn’t nearly as explicit about its racial implications. The four main characters, Jeffrey Beaumont (MacLachlan), Dorothy Vallens (Isabella Rossellini), Sandy Williams (Laura Dern), and Frank Booth (Hopper), are all white; their families, or henchmen in Frank’s case, are all white. It’s easy to forget that the film is set in the South at all: Close to no one in Lumberton speaks English with a native drawl. But there are plenty of black people in the film, more than in any other Lynch film — though they’re mostly in the background, their presence is charged with political voltage, or at the very least, regional color. When Jeffrey, back from college for the summer, picks up Sandy outside of her high school, there are several black students visible in the background. For all its ’50s-retro trappings, Blue Velvet (1986) is firmly situated in the decade in which it was released: The tremendous slowness with which southern states complied with Brown v. Board of Education meant that a scene where black and white students attended the same school could only take place in the near present.

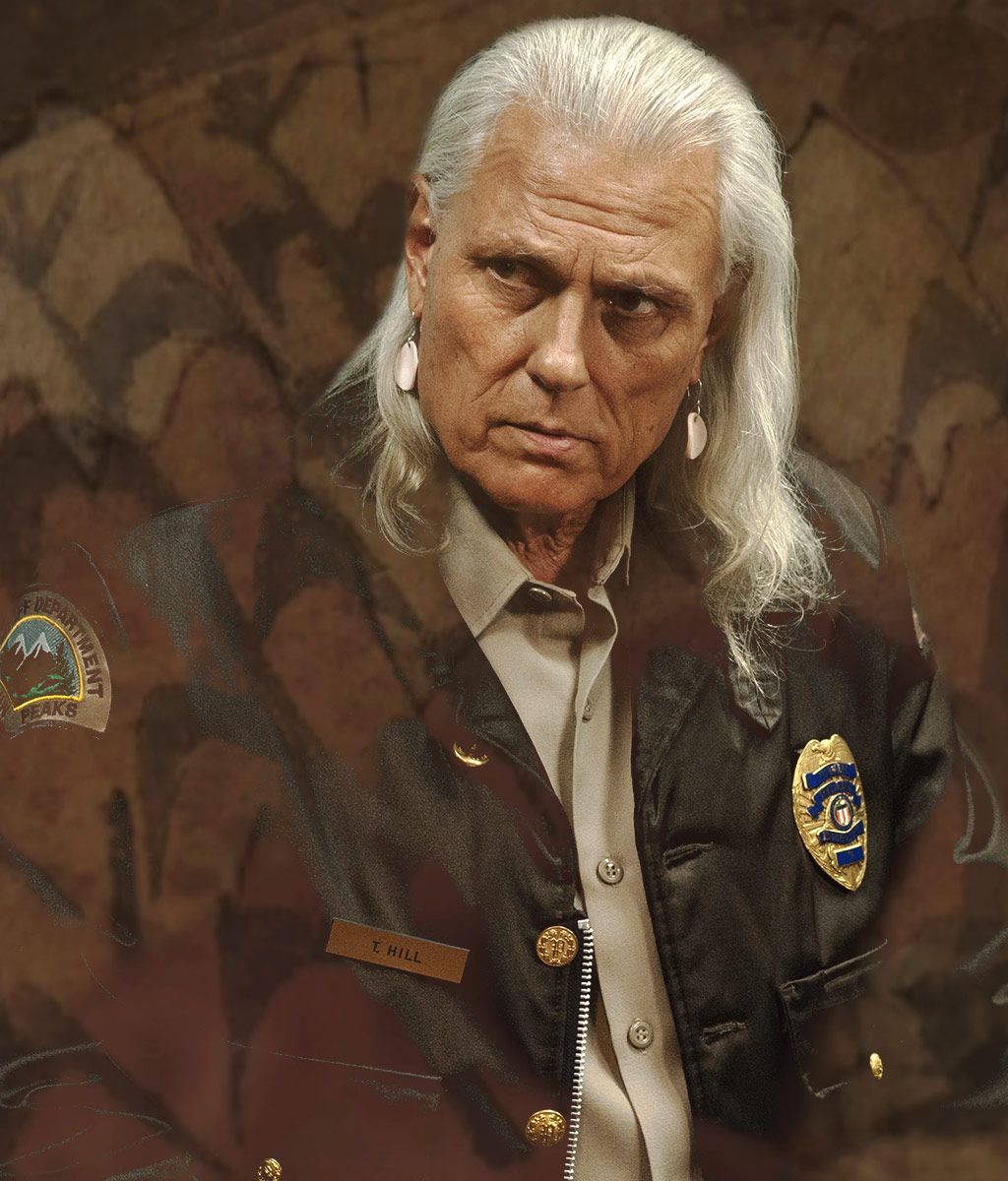

Nor are black people entirely silent in Blue Velvet. Earlier in the film, the viewer learns that the hardware store owned by Jeffrey’s father employs two men, both black and both named Ed. One is blind but remembers where all the items are and all of their prices perfectly; the other, sighted, names the objects on sale so that the prices can be entered into the register. “How many fingers am I holding up?” Jeffrey asks the blind Ed. “Four,” he responds correctly. “I still don’t know how you do that,” Jeffrey says; it’s unclear if he knows that the sighted Ed tapped the blind Ed’s shoulder four times or not. Laughing, he goes on to ask if he can borrow the exterminator rig; “If you want to spray for bugs, Jeffrey, it causes us no pain,” the sighted Ed replies. They’re the first characters of color in Lynch’s films to be associated with recovering memories, but they won’t be the last. Lynch’s protagonists frequently find themselves staggering through an amnesiac fog, and in his most recent works, the figures who try to jog their recollection are frequently nonwhite: Hawk, Jade, and officer Reynaldo in Twin Peaks: The Return; the trio of actors playing homeless people in Inland Empire; Rebekah Del Rio in Mulholland Drive.

And then there are the direct historical references. Dorothy’s apartment building is located on Lincoln Street, a fact accentuated by very loud, very ominous music; likewise, the villainous Frank’s surname matches that of Lincoln’s assassin. Civil War material recurs in Lynch’s works of the same period: In Wild at Heart Marietta’s dogged boyfriend Johnnie Farragut is abducted and killed by Juana and Reggie in New Orleans, the same city conquered by Union admiral David Farragut in 1862; and the tycoon Ben Horne spends much time obsessing over Civil War reenactments during the tail end of Twin Peaks’ second season. The references to the Civil War in Blue Velvet serve a clearer purpose than in Wild at Heart and Twin Peaks, though. Once Jeffrey learns from Dorothy what Frank is doing to her — by holding her husband and son hostage, he’s forcing Dorothy to have sex with him and indulge, while having sex with him, his feral daddy-daughter and mother-son complexes — the film becomes the narrative of his quest to end her slavery. Lynch’s associations of Dorothy with blackness and the blues are muted but consistent: When Jeffrey and Sandy first see Dorothy, presented as “The Blue Lady,” perform, she’s wearing a black dress as she sings Bobby Vinton’s version of “Blue Velvet”; as the song ends, the stage lights dim until her figure is fully enveloped by darkness.

Blue Velvet isn’t directly about race, but it’s definitely not not about race. What clinched the connection for me was the second musical scene. Precisely at the midpoint of the film, Jeffrey witnesses, for the first time, Frank seeing Dorothy perform “Blue Velvet.” Frank’s eyes are closed. His face is full of ecstasy. He’s unabashedly, profoundly moved by the music of a woman he holds in captivity and brutalizes. As someone (as a Frank, even) who writes regularly about black music, it’s long been evident that, however small or great, there will always be some measure of bad faith involved in taking pleasure in art whose beauty, though universal, is rooted in and channels a pain specific to the black experience; though I’m not white, have no wish to be, and benefit rather less from racial hierarchy than both whites and less discerning people of color imagine, the guilt is there all the same. The Blue Velvet scene was uncomfortable and powerful not because it reminded me of what David Foster Wallace would term my essential aloneness (Aloneness), but because it resonated with an American experience so common it’s pointless to call out its grotesquerie. Dorothy’s captor is her art’s most fanatical worshipper. She may be alone, but she’s not the only American in such a situation: There’s not much individual about the fact that white people sincerely and fiercely love art created by people that they, consciously or not, collectively repress for their collective benefit.

It’s hardly unexpected to hear it acknowledged by a rapper: “How you say you feel me when you never had to get through that?” Vince Staples pointedly inquires on “Like It Is.” “We live for their amusement like they view us from behind the glass.” But to have it pointed out, however obliquely (a direct treatment would be inherently self-serving and dishonest), in a scene by a white director, was surprising, particularly when it came from Lynch, an artist who’s never been renowned for real, let alone frequent, depictions of people of color. The Straight Story, Lynch’s vision of the Midwest, is devoid of nonwhites, and Eraserhead, though based on Lynch’s experience of Philadelphia, shows no trace of Philadelphia’s sizable black population: The film hops on the line between the human and inhuman, not on the line separating classes of humans from each other. Meanwhile, out West, the racial other in Lynch’s works isn’t black, but it isn’t entirely absent, either. Its most prominent figures are native, as represented by Twin Peaks upstanding deputy (now deputy sheriff) Hawk in the mountain West, and Mexican — the transcendent singer Rebekah Del Rio — in the California of Mulholland Drive. Both Hawk and Del Rio serve as persistent reminders of a reality overwritten by white conquest, adding a faint, but unmistakable, historical dimension to the return of the repressed that defines Lynch’s work. Characters of East Asian descent, such as Peaks’ Josie Packard, Jonathan Kumagai, Naido, and Ruby, play a somewhat different part: They are, to borrow from the title of curator and critic Dennis Lim’s instructive book on Lynch, the ultimate aliens, truly “from another place.” (Two white women, Catherine Martell on the original Peaks and Diane Evans on the new, are transformed into Asians as a symbol of their estrangement from their significant others.)

None of these images have a new shape, and some require quite an effort not to read them as derogatory. East Asians have long been insulted as having narrow eyes; Naido, the otherworldly being on Twin Peaks: The Return played by Nae Yuuki, has her eyes sealed completely shut. As the artist Niela Orr declared in The Baffler, black women, on the very rare occasions when Lynch gives them speaking roles at all, are cast as prostitutes. (There’s a black woman speaking near the end of Inland Empire who isn’t, but she, like the black man and his Asian girlfriend beside her, is an actress playing a homeless person, so that’s not much better.) Lynch’s focus on archetypes and myths necessarily ties him to stereotype, myth’s depraved stepsibling: He can only wander so far in his depiction of humans who are not white. The deferential black assistant, the noble native guide/sidekick, the soulful duenna, the exotic dragon lady, the kung-fu enforcer, the jet-black lady of the night — all of these images have long been familiar to the American subconscious and American cinema and television, and only a drastic change in the power structure of American society could keep them from recurring there in the future.

It would be easy enough to castigate Lynch for replicating these images, but castigation, for me, seems somewhat superfluous. Misleading, even. To be sure, Lynch’s body of work offers no new roles for people of color, but to expect a white artist dealing exclusively in myths to create new myths for people of color is a self-defeating, not to mention impossible, request. It is nonwhite Americans who must create those new myths for themselves, or else write new lines for the old parts they remain compelled to play.

Far more intriguing is Lynch’s merciless and intimate distension of the mythic images that white America has created and kept to itself. The prom queen is a coke-addicted prostitute and victim of rape; her rapist and eventual murderer is a respectable corporate lawyer, her father. The wide-eyed innocent ingenue actress is a postmortem projection of a failed thespian who had her more successful counterpart and former lesbian lover killed out of jealousy. The business tycoon runs a whorehouse staffed by young women recruited through his department store; he regularly exercises his privilege to break in new employees. The rebel biker is a sweet guy, but helpless. The cowboys are pure evil. The nuclear family? At best a cheerful deception, an infinite nightmare at worst. The local cops are always two or three steps behind the criminals they pursue; federal law enforcement, less flat-footed, is nonetheless never ahead of the game. And the Christian God who underwrites white dominance is nowhere to be found; enigmatic fiends, their facial features invariably white, feasting on pain and sorrow, empowered by oil, electricity, and nuclear fire, run the show instead.

When Lynch introduced FBI Agent Dale Cooper to the world, Cooper, to most viewers, seemed an update on an abiding legend white America had long repeated to itself. Confident, competent, compassionate, and unswervingly just, the agent, in keeping with his namesake Gary Cooper, symbolized the perfect lawman, capable of resolving all crimes, untying all moral knots. And, in keeping with Lynch’s subtle acknowledgements of post-’60s cultural change, he was tolerant of other cultures. Like all of Lynch’s main characters, Cooper was white and psychically sensitive, and he shared Lynch’s affinity for non-Western mystical traditions: Lynch’s oft-stated fondness for Transcendental Meditation and Vedic scriptures is mirrored by Cooper’s immersion in “Tibetan method” and the Native American mythos that Hawk introduces to him. “Do you believe in the soul?” Cooper asks Hawk in the first season; “Several,” he replies. “Waking souls that give life to the mind and the body. A dream soul that wanders.” “Dream souls … Where do they wander?” “Faraway places. The Land of the Dead.” Lynch’s protagonists are white, but his moral geography, adapted from native spiritual traditions, is anything but. For him, evil and good aren’t fixed endpoints on an axis between hell and heaven so much as drifting continents, inhabited by wildlife, that merge and separate in an infinite cycle.

It’s a way of viewing reality that Agent Cooper, in the original Twin Peaks, discovers too late. Cooper’s quest to understand Laura Palmer’s murder leads him onto murkier and murkier moral ground; his being charged, midway through season two, with overstepping his jurisdiction, is a setup engineered by dastardly Canadians, but it’s also a symbol of his inability to remain within the limits of justice. Marred and tedious though it was, the second half of season two didn’t follow Cooper so much as it witnessed the ground under him melting away. (Hawk did warn him: “Cooper, you may be fearless in this world, but there are other worlds.”) By season’s end he had been overtaken by his darker self, possessed by the same evil entity responsible for the murder he had solved.

Much as Twin Peaks heralded the era of so-called prestige television shows, Cooper was the first, and most powerfully drawn, of the morally compromised white male anti-heroes at the center of those shows. He was the first to touch upon the crisis in whiteness and white masculinity that occasioned the appearance (and widespread appreciation) of Tony Soprano, Don Draper, and Walter White. Triggered by the post-’60s changes, white creators and audiences had gravitated toward these figures in order to protect their imperiled self-perception: It was the only way left to center themselves while still passing as cool and deep. Mr. C, the demonically possessed Cooper double of Twin Peaks: The Return, is at once a leathery distillate of this class of anti-heroes and a critique of its essential falsity. MacLachlan, channeling Lynch, plays Mr. C with an inflexible mechanical exactitude that exudes tremendous power but no charisma, as if to remind one that evil, at its core, has nothing cool about it: It simply wants. Its way is what it wants, and it breaks everyone in its way.

The fall of Cooper, the character closest to a Lynch self-portrait, cuts to the heart of his signature achievement as an artist. He has converted, by force if necessary, white America’s simplistic, innocent vision of itself into a complex and incendiary demonology. There has always been a latent contradiction in the phrase “American Dream.” Dreams are the foundation of memories and the house of conscience, but more often than not the success (linked invariably to the possession of white skin) that defines the American Dream demands the forfeiture of memories and conscience. Lynch’s works live in that contradiction and enact its inevitable bad consequence. A society founded on amoral, amnesiac legends of success cannot help but be poisonous: If his art is not an antidote (art is not an antidote for social ills), it is the next best thing, a mirror in which the act of poisoning is faithfully reflected, a toxicology report.

Through the alchemy of cinema, the boundless insularity of everyday American social life is transformed into a nightmare where the white dreamer must confront the fact that the origin of their fears lies nowhere but within themselves; conversely, the day-to-day social exclusion of people of color becomes, in Lynch’s neo-noirs, their exoneration from the possibility of guilt. Nonwhite people are defined by their estrangement from white society, but their images are hardly excluded from white society’s fantasies, where they serve as villainous foils to the virtuous majority: thieves and parasites, cheats and invaders, too robotic or too animal, waste material, a hysterical threat, an unreasoning foe, inherently illegal and beyond the law. Yet in Lynch’s dreamscapes, the people who reveal themselves as villains are nearly always (the misfire of Wild at Heart being the rule-proving exception) white. We encounter there the horror of whiteness without the face-saving transference of humanity’s fouler motives to minorities. (True, the dumpster ghoul in Mulholland Drive and the lesser demons known as Woodsmen in Twin Peaks are played by white actors whose bodies are blackened with soot. But their presentation plays less as an exercise in blackface and more as an acknowledgment that white people themselves are the dark, unnatural beings they should fear.) When other white artists exclude racial minorities from playing central roles, it grates, since those cultural roles confer status and positive moral value; the exclusion mirrors the refusal to take fair account of them in society. The way Lynch places people of color on the margins of his narratives reads differently because centrality for Lynch, an avid disciple of Kafka, is directly linked to guilt. Inclusion is generally desirable, but who wants to be included in another race’s nightmare?

People of color have dreams of their own, and many of those dreams involve entering, at some level, what’s called the American. For them as for everyone, America is omnipresent. Whether they want it or not, whether they know it or not, their lives are structured by the experience of American power, by the United States’ control over oil, electricity, and nuclear fire, and one cannot dream outside of one’s experience. Some dreams have learned to speak for themselves: “Martin had a dream, Martin had a dream, Kendrick have a dream.” (“All my life, I want money and power.”) Some dreams are spoken for: The Sunday of the season finale of Twin Peaks: The Return was also the Sunday when the president announced the repeal of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), the policy which permitted some 800,000 children of undocumented immigrants, known commonly as Dreamers, to remain in the country. Some dreams are driven by fear. The Sunday when a totalitarian state led by wily nonwhites (their memories of being massacred and threatened with nuclear weapons by the American military still fresh) apparently tested its own hydrogen bomb was also the Sunday of the season finale of Twin Peaks: The Return, a show whose most striking episode is centered on the world’s first nuclear test.

It was a good finale. Outside the screen, the world’s fate still resided in the small white man-hands of a TV anti-hero, but within it, Agent Cooper’s shadow self and familiar demon were finally destroyed, and the good Cooper, bright knight of justice, was, at long last, great again. But he wasn’t quite himself, and would become less so. Fobbing off his pseudo-family on Lancelot Court with an affable duplicate, Cooper drives into the desert with his lady love Diane, in search of a new world. Their immigration into dreamland turns them into others. Diane, now Linda, leaves Cooper, now known as Richard, after a memorably painful night together. Driving through West Texas, Cooper finds a woman, a waitress named Carrie Page; her face is Laura Palmer’s, but her memories are different, or at least off. There’s a dead man in her house. She agrees to come “home” with him to Twin Peaks.

The dream world is filled with unlikely coincidence. A sign in Odessa (“USED PARTS”) misspells the car brand Infiniti as INFINITY, corresponding to a vision of the infinity symbol shown to Cooper prior to his entry into the alternate universe; the ominously humming power line pole outside Carrie’s house in Odessa, Texas, is marked with numbers (6, 324810) that match those of another pole near where Mr. C’s son Richard runs over a child in the season’s sixth episode; a weird, orb-like object protrudes from the belly of the dead man in Carrie’s house in much the same way the demonic orb emerged from Mr. C after his shooting; Carrie and Cooper stop at a modern gas station that harks back to an archaic, supernatural gas station shown in earlier episodes. They arrive at Twin Peaks. Cooper’s final words are, in order, a question (“What is your name?”), an apology (“Sorry to bother you so late at night”), a farewell (“Good night”), and another question (“What year is it?”): the mundane words reflect the man, disoriented, on his way out, and with much be sorry for, perfectly. Perfect, too, is Carrie/Laura’s final sound, a dimension-cracking scream that carries to a climax all the female pain and fear at the heart of Twin Peaks. The dream world is filled with unlikely coincidence. But what seems unlikeliest of all is the possibility of putting an end to its suffering; even if the Dream itself ends, the pain at its source seems likely to outlive it.

And it will end. The year is 2017: However you look at it or feel about it, the American Dream as we’ve known it is on its way out, and no one can be sure what or how much will survive its termination. But Lynch’s films, inimitable, rigorous, and decadent, are the ultimate aesthetic expression of the whiteness that possesses the Dream and one of the most urgent moral expressions of the need, if not the possibility, for curing its amnesia with history, abolishing its sadism with compassion. Far from affirming the dream, long-cherished by immigrants of all colors, that they could find shelter in the United States, his fictional universe (following Kafka’s own American fiction) entertains the deep suspicion that once in the New World, they can never settle down. In American society as in American film and television, Asians and natives, blacks and Hispanics are positioned off-stage and on the periphery. What Lynch dares to suggest, in his unique and unsettling fashion, is that even when the whites are on, there’s no one — no one — who’s at home.