Gordon Clark, builder of things, tinkerer, obsessive. Imperfect, well meaning, and utterly square. Gordon Clark, the man always standing right next to the visionary, tweaking and honing and fiddling until the idea actually works. Gordon the seeker, huddled in a closet with a ham radio, reaching out to make a connection. Gordon the failure, Gordon the success story. Gordon, the first character on this series to truly fall, and the only character with the grace to become a side story, a helpmate, and a member of the support staff for his more ambitious, more talented wife. Gordon the father. Gordon the friend. Gordon, who just wants to go camping.

One of the most remarkable, gutsy things about the final act of Halt and Catch Fire is the way it’s propelled itself forward in time, leaping into the ’90s at the end of season three and then skipping forward months and years during season four. It’s been crucial for the show to move swiftly through time so it can deal with its favorite themes: the tsunamis of technological advancement, the drama of making something and then trying to start over, the question of whether people can change. For a show with the word “halt” in its name, it’s always been completely obsessed with time.

So it feels entirely appropriate, beautiful, and sweetly sad that in his last moments, Gordon Clark walks backwards through time. He follows Donna across years, moving from one room to the next. There she is staring at a packet of spreadsheets on the sofa; here’s a lens flare, Gordon crosses another threshold, and there’s Donna in an ’80s skirt suit, handing the girls a snack; one more flare, Gordon passes through another doorway, and there’s Donna again in a bathrobe standing in front of a crib, singing to soothe one of the babies.

Halt and Catch Fire gives Gordon a gift at the end of his life. Gordon’s tragedy and his happiness have always come out of the same fundamental issue: He can see far into the horizon, but never quite far enough. He sees personal computing, but can’t imagine enough innovation to actually change the future. He sees the promise of something like Mutiny, but it’s Donna’s project. He dreams up this program to help Mutiny grow, but cannot implement its far bigger potential. He even saw internet in the home, and he understood Joe’s vision of the browser, but he’s always been one click away from the top of the heap — the company being bought, not the company doing the buying. It’s a tragic position, but it’s also a relief. For a long time now, he’s been the most stable. He’s been the rock.

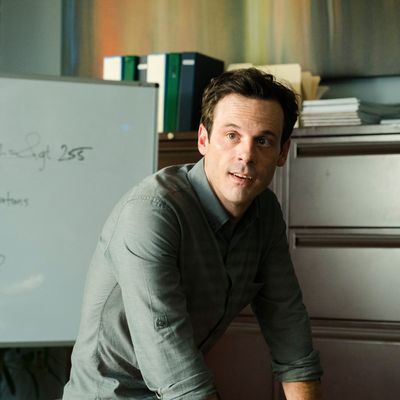

But at the end, Gordon sees it. He hears about the user data from Rover, and he understands the potential for a website that’s not about directing people elsewhere, but about being “sticky.” He has an intuitive understanding of how important it’ll be to become a hub, a community, a gathering place. He has the insight to steer Comet in a direction that could be really revolutionary for the young web, and he has exactly the right combination of cajoling, persuasion, enthusiasm, and chill to communicate the idea to Joe. He gets the word “re-launch” up on the whiteboard.

And then he’s gone. The episode’s title is “Who Needs a Guy,” a refrain that bounces around the Comet headquarters as the electrical system keeps going awry. It’s too hot, and then it’s too cold. “Do you want me to call a guy?” people keep asking, but no. Gordon’s on the case. The big idea is spinning all around them and no one can get anything done because the air conditioning is broken, but never fear. Who needs a guy when you’ve got Gordon? It’s the perfect little story about Gordon’s remarkable evolution since the earliest episodes of the series. He spends his last moments worrying about how to fix his relationship with his daughter, and how to keep the basic operations of his company running smoothly. He’s somewhere in the background, fiddling with the electrical and listening in on Joe’s phone call with Haley. And thank God, he manages to do both.

Other things happen, too. Bos and Diane get married, and it’s both a celebration and an omen. Diane tells Donna that she wants to marry Bos and then step away from her managing partner position because, after all, how does she want to spend the time she has left with him? Donna nods knowingly, while not really knowing at all. Cameron is out in her trailer trying to invent physics engines and self-learning AI to run game bots, and her new benefactor is chiding her to think even bigger.

In any other episode, the big set-piece would be the scene between Joe and Donna, where he comes barreling up to her home, demanding to know exactly why she’d give useful information to her competition, why she’d ever try to help Comet, whether or not he can trust her. “What can I tell you, Joe,” she spits at him. “Shit changes fast.” She’s wounded and furious; Joe is anxious and trying to protect both Haley and his company. It’s a beautiful scene, with both of them screaming at each other about pain and anxiety and the pressure of success, and neither of them fully appreciating how alike they are. Not until the end, that is, when Joe finally sees where Donna is. “I’ve been there,” he tells her, his fingers swollen from being slammed in the door.

What is it about Joe MacMillan that makes people need to smash him up a little? At the end of season three, he had to fall through a floor before the rest of the team could get past his Joe-ness and move on with the idea. Whatever the reason, it’s why he’s still sitting there outside Donna’s house when she walks out with the news. He’s flexing his injured fingers when he looks up and sees her face, and she tells him that Gordon is dead. Donna weeps with Haley and Joanie. Diane goes to tell Bos the news. And Joe returns to the empty whiteboard, staring at the idea Gordon started and now won’t be around to complete.

I am immeasurably sad that Gordon is gone. Over the course of the series, he’s transformed from a thoughtless, selfish partner and an anxious co-worker to someone vastly more introspective, caring, and supportive. Donna and Joe worry about whether they can change, whether they’ve changed too much, whether change is a good thing. Meanwhile, Gordon has been there in the background, proof positive of how far a person can come, and how growth and success don’t have to be big and flashy. The show’s other three main players are still striving for a way to really make it, but all the while, Gordon was figuring out how to be happy. I’m so sad he’s gone, but I’m so thankful that before he went, he’d figured out how to cook, and to have a relationship with a woman who fit him, and to love his daughters, and to be happy with himself. We should all be so lucky.

Random-Access Memories

• In addition to everything else, Gordon’s slow evolution from the start of this series has allowed him to get much funnier. Haley’s hair, he tells Donna, is not quite Dorothy Hamill–length, but not as short as Mark’s. “It’s somewhere mid-Hamill.”

• Donna has been attending some kind of AA meeting, it seems, and when she’s accosted by Joe on her front lawn, she’s in the middle of taking out a huge bag of trash that sounds distinctly like it’s full of bottles. I hope she continues to keep herself on the right track.

• In the final scene of Cameron’s Pilgrim game, which Donna finally beats, the protagonist is embraced by a bigger parental figure after finally making it home. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: Please don’t let Cameron get pregnant at the end of this show.

• I am simultaneously gutted and relieved for Haley, whose last conversation with her dad is mediated by Joe MacMillan. It is completely perfect, except for the fact that they never actually speak. I’d made it all the way through this recap without crying, but thinking about that … boy, it’s getting dusty in here.