Nostalgia for America in the 1970s kicked off in earnest 20 years ago with Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights and has continued unabated ever since. Those who actually lived through the decade might raise an eyebrow at the various films and television series that celebrate what Tom Wolfe in this magazine famously dubbed the Me Decade: that awkward bridge between the chaotic, utopian ’60s and the unapologetic materialism of the ’80s. It’s often the perception of lawlessness, sleaze, and machismo that drives storytellers back to the era of wide-lapel shirts, platform heels, medallions, and cocaine. The appeal lies not in what was actually happening and whom it was happening to, but in a collective sense that the ’70s was the last era in which men could be macho, women and people of color “knew their place,” casual sex wasn’t freighted with fear of terminal illness, and you could say anything that popped into your head without fear of censure. HBO traveled down this pop-culture road just recently with Vinyl, a one-season disaster set against the backdrop of the record industry in New York City. That show flopped, despite its sumptuous production values and superb performances, because it was less an examination of alpha-male narcissism than a celebration of it — Mad Men with louder music and without the layered, intricate sense of history and psychology.

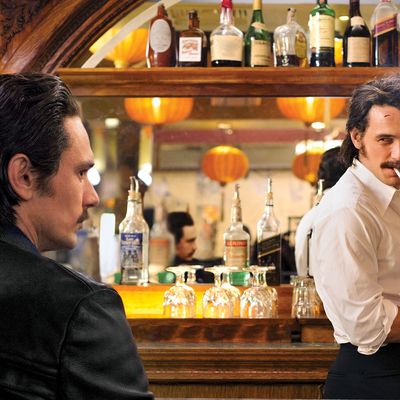

Lo and behold, less than two years later, here come executive producers David Simon (The Wire, Treme) and George Pelecanos with The Deuce, a series about the sex industry that’s set around the same time and in the same city and spotlights many of the same themes and images that drove the network to bankroll Vinyl. But that’s where the similarity ends. This depiction of sex workers and pornographers around Times Square is less a warm nostalgia bath than a cold shower. James Franco, the spread-thin prince of American hipster art, plays twin brothers Frankie and Vincent Martino, whose Times Square bar becomes a front for the Mafia. Maggie Gyllenhaal co-stars as Eileen “Candy” Merrell, a single mother turned streetwalker whose bleak existence takes an upswing when she becomes involved in hard-core porn and realizes that she’ll have more control over every aspect of her life if she can figure out how to get behind that camera instead of performing in front of it. Zoe Kazan plays Vincent Martino’s wife, Andrea, whose infidelity drives him to cheat as well. Gary Carr is C.C., a pimp who seems affable and reasonable enough until you see how he terrorizes his stable of women. His grooming of a fresh-off-the-bus Midwesterner named Lori (Emily Meade) provides a window into the specifics of exploitation: She’s not the oblivious hick she initially seems to be, but she doesn’t control her own narrative in quite the way she imagines, either. A Wire alum, Chris Bauer, plays Vincent and Frankie’s brother-in-law, who seems like a standard-issue audience surrogate until you sense the depth of his fascination with degradation and realize that he’s one of many vehicles through which The Deuce explores its relationship with the audience.

Working with a formidable group of directors — among them Breaking Bad ace Michelle MacLaren, who helmed two episodes, including the feature-length pilot — The Deuce sets an unenviable task for itself: depicting the mundane reality of these characters with understated, at times shocking frankness, never shying away from the particulars of exploitation yet also going out of its way to make the transactions as non-titillating as possible. It might be an impossible goal, and there are times when the series runs up against a truism of storytelling in moving pictures: No matter how scrupulous you try to be when telling a story of physical exploitation, a part of the audience is still going to tune in for indefensible reasons while tuning out whatever context the storytellers try to provide. Historically accurate as its dynamics might be, this is still a series where boorish white men run things and women and minorities are stuck with economic table scraps. Despite the best efforts of the writing staff and Gyllenhaal (who became a producer on the series partly to make sure that her character was well served), there are moments when The Deuce seems to lose its grip on the leash of its worldview and the situations take on a hypnotic power that is presumably not meant to be exploitative but comes across that way anyhow. The scenes of pimps intimidating sex workers and angry men expressing hateful thoughts about women have a low, simmering fury that practically warps the borders of the screen.

This is a risk inherent in the subject matter; there were screenings of Taxi Driver where audiences cheered the psychotic cabbie’s final rampage after two hours of seeing what a sad, damaged person he was. When The Deuce is at its best — as in a long scene where Eileen spends an evening with an entitled, oblivious young man on his birthday and details the various tiers of service with the detachment of an insurance agent explaining a term-life policy — the show achieves the balance between coolheaded representation and you-are-there immediacy that it so plainly seeks. Its most salient virtue is its stubborn refusal to serve up any character who represents a supposedly enlightened, 21st-century-liberal point of view. The pilot includes a lengthy sequence of imminent, escalating violence that over 100 years’ worth of cinema assures us will be interrupted by a bystander who is properly horrified by what he’s seeing. No such luck. On The Deuce, as on The Wire and Treme, it’s every man and woman for themselves, and capitalism against all.

*This article appears in the September 4, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.