When you fall in love with American Vandal, the first thing that hits you is the pitch-perfect silliness of its dick joke. You snicker delightedly at the true-crime style of it all, from the slow-motion push-ins on the discarded can of spray paint to the the graphic recreations of a faceless person moving methodically from vehicle to vehicle (“Dick … dick … dick …”). You shake your head in rueful recognition of the black-and-white photo montage in its opening credits, set to minor string chords that manage to sound both anxious and judgy.

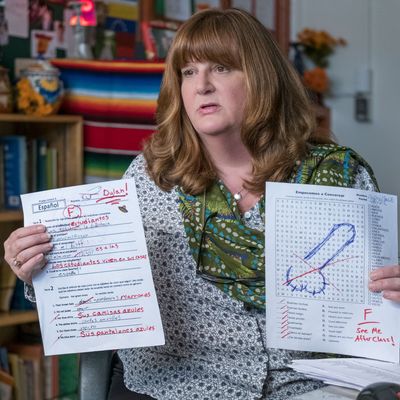

The dick joke is American Vandal’s raison d’être, its alpha and omega. It is as joyfully, simply dumb as you’d want it to be, and it’s profoundly delightful to apply hyperserious, true-crime sleuthing strategies to a question as trivial as, “Who spray painted 27 dicks on cars in the faculty parking lot?” Within the first episode, a revelation about ball hairs constitutes a major case breakthrough. Goofy, giggly-bad wordplay is threaded throughout the show — episode titles include “Hard Facts” and “A Limp Alibi” — and it’s tough to resist a plot point about a dubious hand job that culminates in the voice-over line, “Everything came together, and Alex came alone.”

At some point, though, a switch flips and you realize American Vandal is doing something sweetly sincere beneath that dick joke. I know when it flipped for me: in the middle of episode four, as the mockumentary’s two narrator/documentarians, Peter and Sam, realize they need to prepare cases for themselves as potential dick-drawers. They’re trying to be objective. They both have access to a crucial area of the crime’s cover-up, and if this is going to be a real, serious investigation, they need to try to examine their own possible culpability. Peter makes a case for Sam doing the dicks, and Sam makes one for Peter.

They’re best friends, and they’re deep into the documentary at this point. Sam’s case against Peter is stupid and hilarious, precisely the kind of thing you’d do to tease your best friend in high school. Peter’s motive for doing the dicks, in Sam’s view, would have to be that Peter just really, really loves dicks. His video is full of evidence like a still frame of Peter, his eyes cast down, with an accusatory red dotted line connecting Peter’s eye line to someone’s crotch. Peter watches the video and is incensed. Sam hasn’t taken the investigation seriously! If they don’t present real, thoughtful, hard-hitting evidence, the objectivity of the whole project will be compromised! When Peter then shows Sam the case he made against him, it is both stern and uncomfortably personal. It reveals the kind of teenage secrets you’d never want to be shared with the public — or worse, with your crush. Nearly in tears, Sam charges out. But not before he accuses Peter of masturbating to the American Apparel catalogue.

Look, if your dick joke lasts more than eight episodes of TV, you should probably see a doctor. It’s just not enough to sustain that much story. But to me, this exchange between Peter and Sam was the point when it became clear that American Vandal is much more than just a meticulously erected celebration of male members. It’s also a high-school melodrama, full of cliques and rumors and detentions and hookups. Like most stories in the genre, the series is even shaped by the looming horizon of graduation. You show up for American Vandal for the anatomical humor, but you stay invested because you, too, cannot believe how crazy things got at Nana’s party. (Or why so many kids saved their Snaps about it.)

At times, American Vandal feels like a far more convincing depiction of the high-school experience than the painfully dire 13 Reasons Why, another Netflix original about the mysterious lives of youth. American Vandal has a wildly variable tone that feels truer to the drastic, giddy emotional swings of teenhood, and especially by the end of the series, it rubs dizzy absurdity right up against intense, long-simmering pain. As that Peter-Sam fight demonstrates, neither emotional pole undercuts the other; they’re self-reinforcing, with the inanity of Sam’s video setting the table for how badly Peter’s offering will sting.

The argument between Sam and Peter is the first time that American Vandal’s underlying relationships start to overtake its pure parody elements. It’s also the first scene when the show shifts into its strongest feature: When Peter and Sam realize they need to investigate each other, they wind up facing some of the strongest criticisms of the true-crime genre. They have to consider their own potential biases as filmmakers, how close they’ve gotten to their subjects, and whether or not it’s even possible for people to be objective about other people.

In the episodes that follow, American Vandal starts to eat its own tail. We learn that in the world of the show, Peter and Sam’s investigation is not a Netflix-esque series where everything comes out all at once. It’s released episode by episode, much like Serial, and so Peter and Sam have gained an audience. There are fan theories. There are “Free Dylan” T-shirts. The students at Hanover High are now minor celebrities, and Peter has found himself in something of a pickle. He’s still desperately searching for the truth, but he has to confront the massive gap between the show’s success and the stubborn facts of Dylan’s expulsion and upcoming criminal court case, not to mention his own limitations as a high-schooler.

For me, the trickiest thing about American Vandal is not its turn toward gravity at the end. The most troubling thing about the series is how it satirizes the true-crime genre with ethical concerns and pitfalls, yet it still can’t help but succeed at creating a strong investment in its mystery. American Vandal is just so good at satire that its dick joke flips all the way around once again. You want to know who did the dicks, even while you’re also laughing at the entire enterprise.

Thankfully, it is all a fiction. These are not real kids, and your enjoyment of Dylan’s trip to Priceless Moments can soar unhindered by worries about real lives being ruined and real high-schoolers in pain. Still, it’s a little frightening to consider how effectively the true-crime wheels turn, and how firmly your interest stands to attention when presented with a timelime, a set of alibis, and a wrongfully accused suspect — even when it’s all a big joke.

In her excellent appraisal of the series, The New Yorker’s Jia Tolentino suggests that the one point where American Vandal starts to slip is near the end, when the series “briefly approached the faux seriousness of the documentary within it.” I agree that the show’s ending lacks the almost unbelievably goofy delights of its opening parodic passages, but for me, the end justifies the peens, as it were. The final episode, in which its subjects actually sit down to watch Peter’s documentary, feels like the perfect amalgam of the show’s potent combination of silly jokes, high-school drama, and cockeyed indictment of true crime as a form of entertainment. The dick joke may be how American Vandal piques our interest, but the series ultimately succeeds by plumbing its deeper currents. The best bits look inward at the humanity of high-schoolers like Dylan and Peter and Sam, and then outward to reveal how easily true-crime trappings can get us all obsessed with who actually did the dicks.