This post contains mild spoilers about Blade Runner 2049.

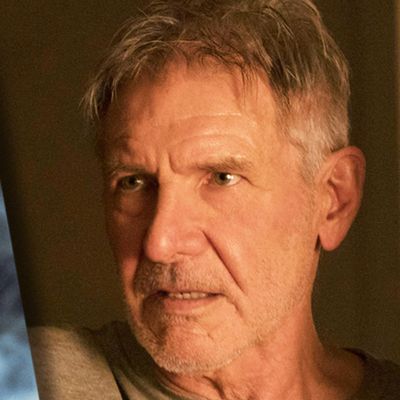

What was the part of Blade Runner 2049 that squicked you out the most? The weird hologram sex scene? Jared Leto gutting that naked replicant? The vision of San Diego as a war-torn hellscape? All of those were pretty weird, but for me, nothing was more unsettling than the moment at the end of the film when Leto tried to tempt Harrison Ford’s Rick Deckard into spilling some secrets by teasing him with a reincarnated version of his lost love: Sean Young’s Rachael, digitally remade exactly as she was in the original Blade Runner.

Maybe it’s CGI Rachael’s appearance in the presence of a septuagenarian Harrison Ford, but I couldn’t help thinking about a similar cameo from Carrie Fisher at the end of Rogue One, another instance of the female lead from an iconic sci-fi franchise being brought back in precisely the form that fanboys remembered her, right down to the weird hairdo. Forgive me for paraphrasing Lady Bracknell, but while to digitally de-age one former Harrison Ford love interest may be regarded as a neat trick, to digitally de-age two points to a disconcerting movement in modern Hollywood blockbusters: Male actors get to reprise their famous roles again and again, no matter how grizzled and wrinkly they are, while women must be content to see their hottest selves frozen in CGI amber.

It’s true that many male stars — Kurt Russell in Guardians of the Galaxy 2, Robert Downey Jr. in Captain America: Civil War, Johnny Depp in the latest Pirates film — have also seen their younger versions revived onscreen. But in every case I can remember, these CGI youngsters pop up in films where their aged flesh-and-blood counterparts also play major roles. Not so with Fisher and Young — their digital doppelgängers are their only appearances in their respective films. (Yes, Rogue One was set in the “past,” but there’s no reason Rachael couldn’t have had a role in Blade Runner; instead, she’s said to have died giving birth to a savior, an old trope the movie does not bother to reinvent.) And while male stars generally get to act in those flashback scenes — they’re digitally de-aged later — in Rogue One and 2049 both Princess Leia and Rachael were played on set by younger stand-ins.

For comparison’s sake, there’s only one recent instance I can think of where a male actor’s younger self has been revived onscreen without the man himself being present in the film: Peter Cushing’s turn as Grand Moff Tarkin in Rogue One. But of course, Cushing had been dead for 22 years; Fisher and Young were both living, working actresses when Rogue One and 2049 were in production.

Two examples do not entirely make a trend, and for all I know, both Fisher and Young were completely fine with seeing their younger selves brought back to life onscreen. Young apparently took the time to give her stand-in some helpful lessons in how to walk like Rachael, while Fisher at least was in a bit of Force Awakens (though compare her screen time in that movie to Ford’s) and is expected to get a proper send-off in The Last Jedi. But when you factor in all the other ways that Hollywood does wrong by older actresses, I can’t help seeing these CGI 20-somethings as one more way for Hollywood to avoid having to write roles for middle-aged women in its blockbusters. Why go through the trouble of creating a role for a woman over 50 when you can bring her back as a digital dream-babe?