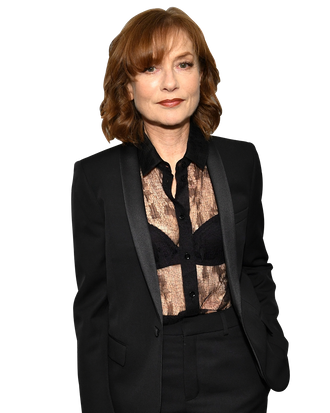

It’s a bit of a surprise to learn that Isabelle Huppert, the real person, is as welcoming as her characters are forbidding. When I meet the fabled star of French art, fashion, and cinema in a single suite on the tenth floor of New York’s Le Parker Meridien Hotel to discuss her new film, Mrs. Hyde, which premiered at the New York Film Festival, she’s immediately warm and good-humored. But fortunately, Huppert never totally abdicates her status as an international woman of mystery: la grande dame winks as she says good-bye.

Mrs. Hyde finds the powerhouse actress cast against type as a mousy wallflower tasked with teaching high-school physics to a belligerent class. For audiences familiar with Huppert’s more typical, Oscar-nominated performance in last year’s sadomasochistic thriller Elle, watching Huppert cower before school administration might require a stretch of the imagination. That is, until the movie’s twist on the benevolent teacher genre, when Huppert’s Madame Géquil finds demonic confidence after being struck by lightning. Vulture caught up with Huppert to talk about being consistently cast as a teacher, why she thinks of herself as a comedic actor, and her love of rap music.

One thing I loved about your performance in this movie is your physicality. You present this character like a bobblehead — physically wobbly, shaking her way through altercations with students and administrators. Is that the kind of thing you work on with a director, does that’s comes from an internal sense of what the character is, or do you look at yourself as you try to create that physicality?

Well, I think it comes from the second option you said — from a kind of internal approach to the character. Once I have decided to do a part, or as I decide to do a part, it’s hard to explain. It’s like an image that grows within myself, with a very precise way of talking and body language. It comes from within me, it’s very strange. It’s almost like the mystery of Jekyll and Mrs. Hyde. It’s a self-transformation, and then it gets very easy to get into the character’s step. Of course, then there’s the research about the costumes. In this case, we had to create this unrealistic character, and the movie is not realistic — but on the other hand, it’s also very realistic when it comes to the social context and what it says about the educational system in France or anywhere in the world, with this scale of where different people come from. But the character itself is completely unrealistic. In one way, it required a lot of imagination, but in another way it also gave us a lot of freedom with the costume designer. Little by little you create a character. And Serge [Bozon, the director] was quite intervening into preparation. He was very much there.

One of the things I was interested in is the movie’s social context — your character is struggling to connect with her students who are Muslim or black, and who come from a different world than what she knows. As you’re doing the work, how do you built the mutual give and take of that cultural relationship?

Whatever is being said in the film about education and social difference was interesting and is what makes the film worthwhile. Not many films have such an accurate statement about what it means to teach. Most of the time when you see teaching, it’s like a caricature. But in this case, you witness the process. In the middle of the film, there is a big scene where I draw lines on the board, and it was very difficult for me because I’m not a math person myself, so it required a lot of learning to understand what I was saying, but you witness the process of making somebody understand. It’s a turning point in the life of this young boy, because finally he understands something. It’s a big effort for her, it’s a big effort for him, but you really had to take the audience to the core of that process.

You’re at a stage in your career where you’re more veteran to the people that are directing you. What’s the relationship with a director like when you’re the person with more experience?

Well in fact, it doesn’t mean anything to be a veteran. It’s the fifth film Serge has done, I wouldn’t certainly not consider him as a beginner, and even if he was, there is no such notion as being a beginner or a more experienced director. Even doing a movie with a first-time director, the director is the director and the actress is the actress. I never put myself in the situation of showing someone to [moves invisible figures with her hands like a Svengali]. I couldn’t. I’ve always worked with people who were completely mastering their subject. It’s exactly like how in this film, there were a lot of nonprofessional actors — it doesn’t make any difference to me to work with nonactors or actors. When it comes to giving life to something in front of a camera, everybody, in a way, is on the same level. I’d rather work with good nonactors rather than bad actors anyway.

This is the second time recently that you’ve played a teacher.

The third time! Someone made me notice that yesterday! Because I was the piano teacher, too.

Do you feel that where you’re at in this particular moment in your career is a place of teaching?

Ah! No. I was asked once to be a teacher in an acting school in Paris. I didn’t do it because I didn’t have time to do it. But no. You learn from everybody. Maybe just by watching someone you learn, but not through actual teaching with rules and explanations. Learning happens more by example or unconscious transmission. But I think I have so much to learn myself that I don’t feel in the position to teach anything to anyone.

One of the things that people respond to in your work is the level of intellectual rigor.

But the intellectual rigor comes from the topic that I choose. Acting is never purely intellectual, or purely physical. Acting is always a combination. This perception you have, which I can understand, has more to do with the subjects that are being dealt with in the movies I’ve done. It’s not about my acting, it’s what the movies are about. It makes people think my acting is intellectual or cerebral, when in fact, it’s not. But let’s say also: It’s possible to show someone onscreen who thinks. And maybe people don’t connect a thinking person with an actress. An actress, in people’s perception, is more about seduction and attitudes, but because of the roles I take, then you can see the thinking. Which is a notion that comes as a surprise to people who connect movies to entertaining.

Well, that was actually my question, because I agree with you, it’s a function of the kinds of movies you’re able to make, and the kind of industry you work in. I think in the United States there are many actors or creative people who want to be doing intellectual work.

But there’s not the material to do it!

Right. What do you think would have to change in the American industry to afford performers the same idiosyncratic and challenging opportunities that you’ve been able to have in your career?

You give me a huge responsibility by answering your question! I wouldn’t change a lot, because you do find directors here that relate to doing movies with a depth of subject matter. Moviemaking is such a broad field. You have really entertaining movies, and then you have more serious movies, and I believe in that. The worst would be if the movie industry was only one dimension. Even in blockbusters you can find great movies, in small independent movies you can find horrible movies. So I’m not too into categories. I’m very open, and also I do what I have the opportunity to do. I’m being given this type of role, but tomorrow, I’d be more than happy to do a big blockbuster or a big action movie, I wouldn’t care. As for changing things, it’s a difficult topic to discuss because it’s a very strong industry, and of course there’s a lot of power. It makes sense that the industry wants to keep that power.

Have you ever been offered a massive superhero or science-fiction movie? I guess Mrs. Hyde is your version of science fiction.

Not yet, I haven’t been offered.

I tend to think of you as a performer who plays women in the moment just before someone loses control, but part of the reason that’s exciting to watch is because as a person, you seem like someone who is very stable and who has a lot of control. Do you ever get bored of not going crazy?

I think I go crazy in my films. In this film she goes crazy in a sense, and in the film I’m doing now, called The Widow. I don’t want to unveil the subject, but it’s certainly someone who is completely crazy. I think I’ve really explored that thin border between what it means to be normal and what it means to be not normal. If you take The Piano Teacher for example, she was experiencing a loss of control.

With the borderline characters like the woman you play in The Piano Teacher, you’re often asked to perform provocative material. People love you because your films become a place to explore those ideas. What was the last time you felt provoked?

So many things in the world surprise you every day, unfortunately, I would say. I’m always surprised by what happens in the world most of the time.

Do you ever feel surprised by films?

I suppose? Yes … I think. Let’s say what I am is very curious. I take surprise as a way of being constantly awakened. Not surprised in the sense that I’m “oh my god” startled out of my chair, but I’m curious about what I see, yes, sure.

There’s also in your movies a balance of darkness and lightness.

Or I would say there’s a balance between guilt and innocence. That’s something I’m always aware of. How to underline the part that innocence plays in a character, which might seem contrary at first sight. It doesn’t mean necessarily that you legitimize behavior, but in most of the characters I play, it was quite easy to underline what I call the innocence of human behavior. In the film I’m doing now, there is no way I can find innocence, and it gave me a hard time at the beginning to figure out how I was going to make this person believable. I can’t tell you much about it, the next time we see each other I can. In this case, it’s the kind of character I’ve never done before.

That question of guilt and innocence can also be a balance of comedy and tragedy. I think of you as a very funny actor.

Oh, I think so too!

But you don’t tell jokes.

Well, I could if necessary.

How do you locate the irony in a movie that might otherwise seem to be dark?

I think that’s my input, that’s my signature. This is the way I am in life. One of the great qualities of Elle, for example, was this opportunity that was given to me in every scene to really put this sense of humor in the film. I like that, and also it takes out any attempt of sentimentality away from the scene, which is my essential rule, otherwise scenes become very sweet, and I don’t like that.

Last and silly questions. Who is your favorite rapper? How do you take your coffee? What was your last dream?

Oh my god, rap, I’m so bad with names I don’t know. I like rap, by the way. I couldn’t say who is my favorite, I can say I love listening to it. It’s nice music and language, too. It plays a lot on the world, for me, it’s a very contemporary expression and it really says something about the interaction between language and the world, but I couldn’t tell you my favorite. I usually take my coffee with a little bit of milk, but I didn’t drink much coffee, until I heard recently that it is very good for the heart. So now I drink coffee. My last dream was a very intense dream but I forgot. You mean a dream of the night?

Yes. Any dreams that aren’t recent you’d like to share for fun?

[Laughs.] No. I’m very selfish. I want to keep it for myself.

This interview has been edited and condensed.