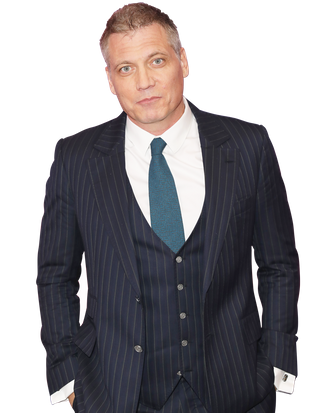

Holt McCallany has done just about every crime procedural: Law & Order, Law & Order: SVU, Law & Order: Criminal Intent, Criminal Minds, CSI, you name it, he’s been on it. While David Fincher’s Netflix series Mindhunter is about FBI agents and serial killers, it’s not a procedural as much as it is a psychological profile of the FBI agents themselves. McCallany plays Bill Tench, the veteran FBI agent of the Behavioral Sciences unit, who’s jaded and in a bit of a rut until he meets Holden Ford (Jonathan Groff), the fresh blood with a wide-eyed obsession with getting into the minds of serial killers. McCallany spoke to Vulture about whether he could recognize a psychopath, what’s to come for a second season of Mindhunter (Charles Manson, of course), and what his own father was like.

How did your parents come to name you Holt? Did they name you after a relative?

Holt was actually my grandfather’s name. His name was Holt McCallany, and I have cousins in Ireland who are also named Holt. It’s a family name, and I’ve grown to love the name. When I was a little boy, I didn’t like the name Holt, so I changed my name to Rex because I thought that Rex sounded tough and I went around the neighborhood and I told all the other kids they have to call me Rex now. They would come to my house and be like, ‘Is Rex home?’ And my mom was like, ‘Who?!’ And then one day, I was in the school library and I found a book of name origins and I looked up Holt and it said “knight of the forest.” And I thought, that sounds pretty cool. I grew to love my name and nobody calls me Rex anymore. But you can if you want to.

No! I think Holt is a cool name.

Thank you. Now I’m grateful to have an unusual name. For an actor, it just makes you stand out a little bit.

You worked before with David Fincher on Fight Club: Was he the one who brought you on for Mindhunter?

Yeah, so David is in charge of every aspect of our production, and obviously one of the big considerations is casting, so he does all the casting with a woman named Laray Mayfield, a very wonderful casting director who casts all of David’s projects.They sent it to me and I shot a tape and sent it to David’s office. Afterward, he brought me in for a meeting and we had a nice conversation, and from that point forward I thought, there’s a really good chance this could work out.

David Fincher has a reputation for being very precise. Were there certain things about the show or your character that he was particular about?

Well, he is a very precise guy. Very meticulous. Nobody’s more driven than David to get things as good as they can possibly be, but he’s also a collaborative guy. I remember there was one particular email I got from David, where he shared with me some of his thoughts about who Bill was and what stage Bill was at in his life. His idea was that this is a guy who has a troubled marriage and an adopted son who has psychological problems with whom he has a very difficult relationship. He’s also a guy that’s not interested in the internal politics and the bureaucracy at Quantico. He doesn’t want to do the kinds of things that you would have to do in order to get promoted, so he kind of runs away. He teaches road school. He’s out on the road, teaching local law enforcement, and playing an occasional round of golf. I’ve always thought of him as the kind of guy who, when we first meet him, is floundering. He’s forgotten why he wants to be an FBI agent. Then Holden comes into my life and everything changes. That was his take, but then it’s up to me to take that and to make it into something.

Do you think you could recognize a psychopath if you were talking to one?

You do become a lot more aware of subtle things in people’s gestures and mannerism. Actors are similar to detectives in this respect. We want to physicalize in order to understand more clearly. What does that mean? It means like, “What is the actual blocking?” if I can use that word. “What is the blocking of a particular murder?” So, the killer: How did he get into the house? Did he come through the door? Was the door unlocked or did he have to break the lock? When he entered the room, was he carrying a weapon or did he have it concealed? Did he go straight to the bedrooms or did he move through the house? Did he rape the woman first? Or did he tie her up? What did he actually do? And you have to be able to visualize yourself through every step of that process to try to understand, “Okay, then he did this, then he did that.” Let me put it on its feet, let me see if I can understand exactly how this guy did what he did by walking through it in my mind.

Was it ever taxing to be thinking about serial killers all the time?

The guy I play, Bill Tench, is loosely based on a real FBI agent named Robert Ressler. Robert Ressler wrote a book called Whoever Fights Monsters and that’s from a quote by Friedrich Nietzsche, which is “Whoever fights monsters should be careful they do not become a monster, and when you look into the abyss, the abyss also looks into you.” So these guys are obsessed with these killers and these crimes. Why? Because they want to catch him before he can commit a similar crime on somebody else. They really feel like they are protectors and that they fill a very important role in society. So they’re constantly thinking about it, constantly going over and over it in their minds: the crimes, the details, all of the grizzly aspects of it that people don’t want to confront. And they do pay a price for it, emotionally and in terms of their relationships, but also some of them physically. You see it over and over again, they drop weight, they have a heart attack. John Douglas had a full nervous breakdown. Post-traumatic stress disorder. That really happened. It’s in the show, it’s in the book, and it’s in his life.

We do a tremendous amount of research on the show because you have to understand each of these killers and their histories and the crimes they committed. So, you’re reading about Ed Kemper, but you know that next week we’re going to start shooting Jerry Brudos. I’ve gotta understand who Jerry Brudos was, and I have to understand who Richard Speck was, and I have to understand Monte Rissell and, going forward, Charles Manson, David Berkowitz, and on and on and on. And volumes have been written about these guys. I can’t play those scenes unless I’ve really understood who they are and what they did and how they’re different from the other guys. Also, you want to be able to make suggestions. You want to be able to make a contribution in rehearsals. You can’t do that unless you’ve done your homework. So, it’s constant homework. The day doesn’t end when you get back from the set because there’s always research you have to do for upcoming episodes.

How does that not fuck you up a little bit?

No, look, it does. You’re looking at these guys and the emptiness of their souls and the depravity that makes them commit these horrible acts and it causes you sometimes to recognize certain emptinesses that exist within yourself.

Do you think the show is saying something about masculinity in America?

Do I think the show is saying something about masculinity in America?

Yeah. [Laughs.] Like a commentary.

Don’t get me started on the subject of the feminization of the American male because I could speak for 300 lifetimes on that subject. Look, it’s a different time. It’s a different time and it’s a different place, and the kinds of crimes that these men committed are not the same kinds of crimes that we see today. Now when people commit mass murder it’s usually for religious motivations. They’re jihadis, right? They’re terrorists. And they just blew themselves up and killed a bunch of people. Well, that’s not what these guys were.

Well, there are also a lot of mass killings that aren’t religious. Like the mass shooting in Las Vegas.

Well, that’s a good example. He’s a spree killer. He’s not a serial killer. It was one act. In which he massacred 58 people I think it was. So, you’re right, and it’s a little bit of a different situation because there’s not a profile. We know who the killer is. When we’re making a profile, we don’t know who the killer was, so we’re trying through a process of elimination to eliminate the most unlikely groups of people. So, most of this violence is male on female, so we can probably assume the perpetrator is a male. Most of these killers are in their 20s or 30s. Almost all of these crimes are intra-racial. It means white guys kill white women, or if they’re gay, other white men. It’s very rarely white on black or black on white. That’s how it is. Is he an organized or a disorganized criminal? What does the crime scene tell me? What do the wounds that were inflicted on the victim — what can I glean from that? Did he take steps to ensure he wouldn’t get caught? Was he suicidal? What was his relationship to those victims? Why did he choose those people? What did they represent to him? These are all the questions guys in the FBI have to ask, but I do think that we have seen a change. It’s not that these crimes don’t exist anymore, but they’re not as common as they were in the period we’re dealing with in the show.

What do you think was motivating them then?

This is one of the fundamental reasons why the show is so interesting. It’s because there was a point in time when a murder was committed, the motive would be impossible to deduce. People murdered for financial gain, for jealousy, for revenge. But when guys start murdering complete strangers and then mutilating their corpses, you have to ask, “What the heck is the reason for this?” And there are certain commonalities. For example, in almost every single case you see a domineering or abusive mother. You see an absent or alcoholic father. Fully 40 percent of the guys that were studied in the study that we do were the victims of some kind of child abuse, sexual or otherwise. So, you start to look at the warning signs. Nobody wakes up one day, after having lived a perfectly normal life for 30 years, and then decides to become a serial killer. It’s an evolution. They grow through phases and there has to be some kind of an event that triggers them from going to contemplating these kinds of crimes to actually committing them.

But I don’t know, it’s a really fascinating question to say, “Is there a relationship in a post-feminist America between the way that male-female relationship has changed in the since 40 years, and does that have a bearing on the prevalence or the lack thereof of sexually motivated homicides?” I think it’s a fascinating question. It’s a good one for our writers to ponder. I know they’re deeply pondering whether or not it’s possible to rehabilitate these criminals because when these guys commit these horrible, ghastly acts, what chance is it they’re after that they can really return to society? Can they be rehabilitated? Particularly with all the problems we have in our prison systems, I’m not hopeful that they can.

Speaking of kids, I assume your character is worried that his adopted son might have some of these “warning signs.”

Well, that’s a really interesting idea. Something that was kicked around in the writers room. I don’t know if we’ll be dealing with that particular story line going forward. They might consider it a little too on the nose in a certain way. But the kid is troubled, and I have great difficulty communicating with him. And you have to remember, in 1978, fatherhood was different for many of these men.

I’ll tell you a true story. When I was born in Mount Sinai hospital in New York City, my father, while my mom was in labor, was a couple of blocks away from the hospital in an Irish pub watching the Jets, and at halftime he came over to the hospital and he happened to arrive just a few minutes after my birth. And he said to the doctor, “Is it healthy?” And the doctor said, “Yes.” “Is it a boy?” “Yes.” And then he turned to my mom and said, “How do you feel?” She said, “I’m fine.” He said, “All right, well, I guess I’ll go back and see the rest of the game.” And until the end of his life, he always said, “I knew that Holt would be a good guy because he had the class to be born at halftime.” That’s a true story. It was a different time. He didn’t like hospitals. He’s not going to be in the delivery room. That’s a midwife’s job, he’s not going to do that. And he’s not going to change diapers, either. That’s not what they did. Look, I had a complicated relationship with my father, but one thing I’m grateful for is that I understand very clearly what the mentality was of a certain kind of a guy in 1970s America because I grew up with those men.

Do you think that having more sensitive, engaged fathers is better for children?

Well, look, my father was a chronic alcoholic and that is a terrible disease and it tears apart families, so I would say it’s better not to have an alcoholic father if you can avoid it. But, I also grew up around men who caused you to be self-sufficient, and independent, and they valued physical courage and they had a different mentality. A lot of that I carry with me, and I don’t have regrets about that.

This interview has been edited and condensed.