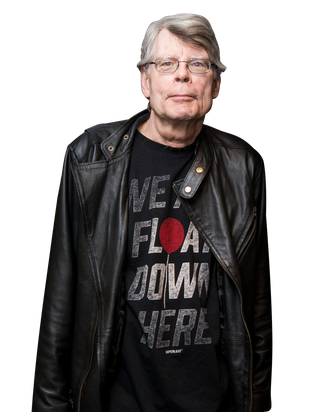

Stephen King turned 70 last week, and he’s got plenty to celebrate. The prolific author is having a major moment this year as the film It, adapted from his 1986 novel, has become a box-office phenomenon. Everywhere you look, though, there’s some new King project in the works, whether it’s the recent movie version of The Dark Tower, the limited series Mr. Mercedes, or Hulu’s upcoming show Castle Rock. In addition to his latest book Sleeping Beauties — written with his son Owen — King has two other new, well-reviewed movie adaptations hitting Netflix: Gerald’s Game, based on his 1992 novel and available now, casts Carla Gugino as a woman who’s handcuffed to a bed by her husband (Bruce Greenwood) in a role-play scenario gone wrong. 1922, adapted from a King short story and out October 20, stars Thomas Jane as a flinty-eyed farmer named Wilfred who plunges into madness after the murder of his wife. As King told me on the phone a few days ago, he couldn’t be more pleased about the movies and his banner year.

This is a real boom time for you when it comes to adaptations of your work. Do you think that a generation raised on your books is newly eager to bring them to the screen?

I don’t know! It’s kind of a perfect storm, isn’t it? A lot of these things came up all at the same time, and I don’t think there was any particular reason for it to happen. It’s like a farmer having a really good year. [Laughs.] In 1922, when Wilfred says, “We had a really good year for corn then,” well, I had a really good year for corn this year. There are other factors: Some of the recent things have been successful, like the miniseries of 11/22/63, and I think when that happens, people say to themselves, “If X succeeds, maybe Y will.” But I’d like to think a lot of it is just the material, that people see something in these stories that would be visually arresting.

How do movies like Gerald’s Game and 1922 get pitched to you? Do the directors ever ask you for advice?

Well, that’s not my job. I love the movies, Kyle. That’s all I can tell you. I do! Even the worst movie I saw was fuckin’ terrific. As far as I’m concerned, if somebody wants to make a movie [from my stories], I’m behind that idea and I’m always interested to see what they come up with. With 1922, was I a little surprised that somebody wanted to make it? I was, and I was also pleased by the challenge of it and anxious to see what would come out. And you know, what 1922 reminded me of was a film called There Will Be Blood. It has the same kind of flat, dead-eyed, affect to it, so it made for a really good suspense picture, and it’s a movie that won’t leave my mind. It has this sort of poisonous effect, it just sort of sticks there because some of the images are so good.

And there are some juicy lead characters in these. How did you feel about Carla and Bruce in Gerald’s Game?

I had casting approval and I approved them immediately. I knew their work, of course. Bruce Greenwood had worked for a while on [the King-penned musical] Ghost Brothers of Darkland County and I’m just sorry he didn’t get to sing in Gerald’s Game, because he has a terrific singing voice. It was a no-brainer for me. The script broke the book open to get to the interior part of the story in a way that I thought was terrific.

You weren’t writing these stories with the actors’ faces in mind, so what is it like when you see people bring these characters to life? Who’s done it well, in your opinion?

Carla in Gerald’s Game is a good case in point: She understood that character and, frankly, she played the shit out of it. Once she decided that she wanted to do it, she just went right to the wall with it. Just a fantastic job. I’ve said this before, but Jack Nicholson in The Shining, not so much. River Phoenix in Stand by Me was amazing, Kathy Bates in Misery did a terrific job, and you know, Tom Jane in 1922 really did it. He really got that stiff-necked, “I’ll do anything to keep my land” character. He’s terrific.

You’re on the record as having a very sanguine attitude toward adaptation. A few years ago, you told Rolling Stone, “The movies have never been a big deal to me. The movies are the movies. They just make them. If they’re good, that’s terrific. If they’re not, they’re not.” But did you always feel that way?

I never had a problem with it, from Carrie onward. Even with Carrie, my feeling was, “They’re gonna make this movie. If it’s a success, it will help me do what I want to do, which is to write books.” When I was in college, I read something that stuck in my mind from James M. Cain, who did The Postman Always Rings Twice and Double Indemnity and Mildred Pierce. He did an interview near the end of his life where the reporter said, “They ruined your books for the movies,” and Cain snapped his head around and pointed at the bookshelf and said, “No they didn’t, they’re all right there.” In a way, the book is untouchable.

Now, what Hemingway said is that the best thing that can happen to a writer is when they pay you a lot of money for it but never make the movie. I’ve never felt that way, I’m always anxious to see what they do with it. Sometimes they succeed, and sometimes you get pictures like the Children of the Corn sequels. I’ve been down this road before in the sense that a movie like Gerald’s Game or 1922, it’s easy to say, “This would be really difficult to make into a movie,” but I felt that way about Cujo and they did a terrific job, so you never know what’s going to happen. The attitude has to be, “I will get involved if you want me to get involved and I have these controls over who’s going to be in the cast and who will write the screenplay. I’m happy to do that when you understand that 90 percent of the time, I’m going to say, ‘That’s fine, go ahead.’”

I think part of my laissez-faire attitude comes from a) I’m doing okay financially so I can afford to take a risk, and b) I’ve been prolific enough so that I don’t feel upset about it. Take a guy like William Peter Blatty when Friedkin made The Exorcist: That was his baby, so it was probably an extremely important event in his life. Same thing with Ira Levin, who did Rosemary’s Baby. He was terrific, but he only wrote four novels, so when Polanski wanted to make Rosemary’s Baby, Levin was very anxious that he follow the book very closely, right down to the kind of shirts that the John Cassavetes character wore. I’m not that guy, I’m just not. My idea is, “If you’re going to make changes, hopefully they’ll work.” There are changes in It that work very well, and with Mr. Mercedes, which is on TV now, there are some terrific changes from the book. Sometimes you make those changes and they don’t work really well, and I’m always sorry when that happens.

Is there any common thread you’ve been able to figure out when it comes to good adaptations of your work?

I think that sometimes when people buy a book, they just want the situation and then they’ll build the movie off it. It’s like buying a launch pad and putting your own rocket on it: Sometimes that works, and sometimes it explodes. A lot of times, I feel like the filmmakers are better off if they follow the arc of my stories closely. Now, maybe that’s egocentric, but that’s the way I feel. With Gerald’s Game and 1922, they both follow the course of the books pretty closely, and the films that these guys made stand and fall on that.

What is it like for you when you see some of your older stories, like Gerald’s Game and It, placed into a more contemporary time period for their adaptations?

With It, it made sense to simply take the idea of the book — which has this 20-year gap between the children and the adults — and move it forward so that we could set the adults in the next movie pretty much in the present-day. Not right in the present day, but pretty close to it. And as far as I’m concerned, the story behind Gerald’s Game stays pretty current whether it was published then or in the early ’90s. The themes of the book — repressed memories, and the way women are treated and abused — they’re important today, and you’ve still got a lot of issues that have to do with how society treats women. I mean, you can’t get anymore on-the-nose than a woman in handcuffs, can you?

I would imagine there’s been renewed interest in some of your adaptations in the wake of It. I know that directors like Ben Affleck and Josh Boone had flirted with a two-film version of The Stand, and I’d heard that your novel Insomnia would be potentially turned into a virtual-reality series. Any updates?

You just never know until it’s gonna happen, but the VR thing is still percolating away. I don’t think it’s dead or anything like that, although I haven’t heard about it lately. There’s talk about another thing, an animated feature, but I can’t tell you anything further — it’s a secret. That looks like it might happen. There’s talk about doing The Stand as an extended TV series, possibly for Showtime or CBS All Access, and there’s been some interest in developing Salem’s Lot as a feature, probably because people are saying, “Well, we took an old miniseries called It and turned it into a phenomenon, so maybe we can do it with something else.” Nothing succeeds like excess!

You’re now on the other side of The Dark Tower, a movie that was so long in the making but didn’t completely work. What was the challenge there?

The major challenge was to do a film based on a series of books that’s really long, about 3,000 pages. The other part of it was the decision to do a PG-13 feature adaptation of books that are extremely violent and deal with violent behavior in a fairly graphic way. That was something that had to be overcome, although I’ve gotta say, I thought [screenwriter] Akiva Goldsman did a terrific job in taking a central part of the book and turning it into what I thought was a pretty good movie. The TV series they’re developing now … we’ll see what happens with that. It would be like a complete reboot, so we’ll just have to see.

How long do your stories linger with you once you’ve finished them?

I care about them all. I care about some of them more as books than as movies. I do have a special place in my heart for a miniseries called Storm of the Century because I thought everything worked there — it was a dream project. There was another original miniseries I did called Golden Years that I have a place in my heart for, and some of the books like Lisey’s Story and 11/22/63 and Under the Dome mean a lot to me because I can remember writing them in this kind of dream state, feeling like nothing could go wrong. I keep them all with me, and if somebody asks me about a character or a piece of plot from the books, I’m never in a position — and I bet James Patterson would be in this position — where I’d have to say, “Oh, gee, I don’t remember that at all. It was so long ago!” I remember them all. They’re all my friends, and some of them are my lovers, if you know what I mean.