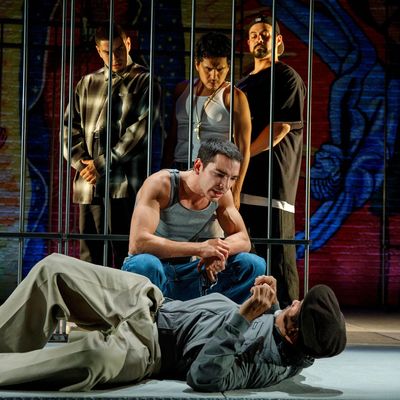

When you enter the PublicÔÇÖs Shiva Theater for Oedipus El Rey, the setting of Luis AlfaroÔÇÖs transposition of SophoclesÔÇÖs tragedy becomes immediately and elegantly clear. The Shiva is a wide, shallow space, and scenic designer Riccardo Hernandez has covered the cinder blocks of the back wall with the kind of ecstatic, haunting mural that might adorn the side of a building in southern Los Angeles: all roses, orange trees, and colorful depictions of angels and the Virgin Mary in the Mexican tradition. In front of the wall are sliding panels made of prison bars, along with two ugly concrete columns. Religion and hard reality sit side by side: the faith of a community and its all-too-frequent fate.

The community in question in this Oedipus is that of the barrios in South Central L.A. Alfaro is meticulous with his geography ÔÇö in his script he lists the storyÔÇÖs locations down to the Zip Code (ÔÇ£La Casa: 1324 Toberman Street, Pico-Union, L.A., C.A., 90015ÔÇØ). His mission here is twofold: rework a Greek tragedy, and use its themes of fate and free choice to examine the ugly cycle of routine incarceration and gang violence that holds the Chicano neighborhoods of his home city in a suffocating, seemingly unbreakable grip.

His play is more successful in the latter of its aims. As ÔÇ£a story about the systemÔÇØ (to steal the words of the playÔÇÖs Chorus), its anger is clear and its thrust pointed, even if it tends to favor telling over showing. As a riff on Oedipus Rex, however, the play starts to feel muddled. By changing his focus to the action that takes place before the plot of Sophocles begins, Alfaro inadvertently lowers his own storyÔÇÖs stakes, filing the edge off of the deadly dramatic irony that sits at the heart of his source material.

A refresher: SophoclesÔÇÖs play begins with the people of Thebes begging their king, Oedipus, to dispel the plague that has fallen on their city by finding and punishing the murderer of the former king, Laius. In his ignorance and his hubris, Oedipus dedicates himself to discovering the murderer and saving the city. Of course, he is the droid heÔÇÖs looking for. He is the long-lost son of King Laius and Queen Jocasta, left for dead as a baby because of a prophecy that said he would kill his father ÔÇö only to return to Thebes years later as a stranger, bump off Laius in a roadside brawl, marry the kingÔÇÖs widow (his own mother), and become the new king.

SophoclesÔÇÖs Oedipus has a clear task: Solve the mystery. Find the killer. AlfaroÔÇÖs Oedipus ÔÇö who starts his play as a young man newly released from prison, far from the fateful marriage or ÔÇ£kingshipÔÇØ that await him ÔÇö has a much more nebulous drive: to write his own story. ÔÇ£Motherfuckers been writing my story since I was born,ÔÇØ says one of the ensemble at the playÔÇÖs beginning (they all pass in and out of the Chorus, here individually called ÔÇ£CoroÔÇØ). ÔÇ£HeÔÇÖs got a story,ÔÇØ calling Oedipus out of the group. ÔÇ£This cabron wanted to be ÔÇÿthe oneÔÇÖ ÔǪ Yes, a man who wanted to be ÔÇö something more.ÔÇØ

This is well-trod terrain ÔÇö every Disney protagonist from Mulan to Hercules has had the same basic goal. It doesnÔÇÖt have to feel hackneyed, especially when voices like AlfaroÔÇÖs, voices from underheard communities, are speaking out. But often this Oedipus, both play and character, seems flattened out. As Alfaro checks off the boxes of the Greek tragedyÔÇÖs backstory ÔÇö the prophecy, the crippling of baby OedipusÔÇÖs feet, the oracles, the riddle contest with the Sphinx, the roadside murder of Laius, the marriage to Jocasta, the assumption of LaiusÔÇÖs throne ÔÇö he tends to drain the source material of its cosmic horror, ending up with a plodding coming-of-age story to which we all know the inevitable end.

As Oedipus, Juan Castano struggles to find depth and passion in a role thatÔÇÖs not defined by much save a desire to define himself. ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm going to write my own story,ÔÇØ he says as he gets out of prison, where he has been raised by this playÔÇÖs Tiresias figure, a surrogate father that he believes is his own (a stoic performance by Julio Monge). ÔÇ£I donÔÇÖt got much of a story yet,ÔÇØ he confesses to Jocasta when they become lovers. ÔÇ£I wanted to make a new story,ÔÇØ he rails when he finally learns the truth of his own identity. ItÔÇÖs hard to keep speaking ÔÇö and hearing ÔÇö lines like these without feeling caught in a kind of thematic hamster wheel. Yes, we know this is the playÔÇÖs supertask, but it would be great if the protagonist werenÔÇÖt constantly forced to inform us of it.

Sandra Delgado maintains a focused dignity as Jocasta (though its hard to read her as truly old enough to be Castanos mother), but she too falls victim to a series of on-the-nose dialogues about the Big Ideas at the center of her own play. Its about the old ways here, she tells Oedipus, who affronts the barrio folk with his skepticism. You might think you have the power to make the world you want to make, but theres someone upstairs pulling your strings. You think you got here on your own?  We all got a story that was written for us a long time ago. Were just characters in a book  Our story has already been told.

In earnest back-and-forths like this one between Oedipus and Jocasta, AlfaroÔÇÖs characters can end up feeling less like people and more like mouthpieces: In this corner, Destiny! And in this corner, the challenger, Free Will! (This effect isnÔÇÖt aided by director Chay YewÔÇÖs somewhat static staging. His ensemble is playing in a mostly empty space, and though there are some tightly choreographed combat and movement sequences, the physicality in debates between characters often feels a bit ungrounded.) The big ideas hit harder when Alfaro doesnÔÇÖt name them: When Oedipus is leaving prison, Tiresias assures his ÔÇ£sonÔÇØ that he too will be out soon. ÔÇ£How do you know?ÔÇØ asks Oedipus, and Tiresias laughs coldly: ÔÇ£This is an industry, mijo. Every time someone comes in, a ker-ching ker-ching goes off at the State Capitol. They gotta kick us out so that we can get back in. Over 1 million served.ÔÇØ

In roughly the last ten minutes of Oedipus El Rey, Alfaro attempts to pack in the entirety of Oedipus Rex. Tiresias gets out of jail just in time for Oedipus and JocastaÔÇÖs wedding day, rolling into town like a seriously bummer version of Dumbledore, ready to explain it all to our young hero. ItÔÇÖs a rushed and confusing climax. How does Tiresias even know about the man Oedipus killed? Why, having just learned that heÔÇÖs sleeping with his own mother, does Oedipus get into a debate with Tiresias over the nature of fatherhood, instead of immediately reacting to the the harrowing truth of himself? Why does this Oedipus force Jocasta to gouge out his eyes, rather than owning his storyÔÇÖs climactic act? The dramatic tension hasnÔÇÖt had a chance to build under his surface. So when it comes time for him to experience earth-shattering revelation, he has about 30 seconds to get there, and thereÔÇÖs just not enough gas in the tank. AlfaroÔÇÖs Oedipus undoubtedly examines a world thatÔÇÖs ripe with narrative potential, but tonally, he ends up shrinking the play instead of widening its scope. ThatÔÇÖs a pity, since a story like that of Oedipus ÔÇö Rex or El Rey ÔÇö should feel infinitely expansive, even as its hero struggles against the prison bars of fate.

Oedipus El Rey is at the Public Theater through December 3.