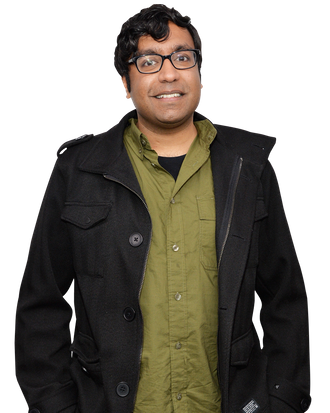

If you didn’t know Hari Kondabolu last month, you might know him now. The 34-year-old comic from Queens has seemingly been everywhere this fall, anchoring a raft of print, radio, and online coverage of his documentary, The Problem With Apu, which premiered Sunday on TruTV. The Indian-American resentment of Apu isn’t new to the people Kondabolu roped into the documentary, most of them South Asian–American actors and actresses such as Kal Penn, Utkarsh Ambudkar, Aziz Ansari, and Sakina Jaffrey (full disclosure: This writer appears in the documentary as well), but it can still confound those untouched by the shadow Apu casts, one of the imbalances that inspired Kondabolu to make a movie analyzing the cartoon character in the first place.

The term “soft racism” comes up frequently in coverage of the documentary, a term evocative of another recently in the news, “hipster racism,” after novelist Zinzi Clemmons used the latter to indict a wide section of the comedy world. In a Facebook post that went viral, Clemmons disavowed power players who excuse transgressions as “jokes.” Kondabolu’s frustration with The Simpsons similarly stokes easy dismissals, from the very people tasked to change things: Call out Apu, and you inevitably hear that The Simpsons makes fun of everyone, that its characters are all caricatures, that if you can’t take a joke, you should get out of the glow of the TV. As Ambudkar, the actor who voices Apu’s son in an episode created to update the character, after complaints went public, puts it: “The Simpsons always wins.” In Kondabolu’s doc, Ambudkar describes his regret when watching the episode after it aired. As he read it, its writing was designed to make critics of Apu look sillier than the character himself.

Nothing’s simple in representational politics. Vulture recently sat down with Kondabolu to discuss the making of a movie few comics would touch with a pole, how he positioned Apu in the annals of American race politics, and what lies ahead after tackling his nemesis, gloves off.

You got quite a crew.

It was almost everybody I wanted.

How’d you get them?

It was personal. It wasn’t something where I had to convince them. Think about the culture we’re in now. It’s not that everyone’s more thoughtful, it’s that you’re scared to not be thoughtful. You want to be on the right side of history, and you don’t even think about that character. Well, we think about it. Most of the people I pitched to, it’s like oh my god for them, it’s sitting right there.

It was fun to make a movie and to interview so many people, but the actual heart of the issue, it was a 101 course. I honestly wanted to call it Seriously? I need to explain this? Because we all know this. It’s obvious. But I had to educate people. There’s a part of the film where I had to be reminded, this is going to mainstream America. This isn’t a film that’s in festivals. I need to explain basic ideas. I really need to explain minstrelsy? I really do? And I’m like, yeah, I do. This stuff used to be called “inaccessible” though. We’re at least in the era where it’s now mind-blowing.

How do you think in terms of an audience where you are starting at square one about issues that are almost old hat to you?

You find the common ground. If I talk about the minstrelsy, that’s hard. If I talk about The Simpsons, we have shared ground. It’s this classic show that’s global.

The issue isn’t so much the character. I’m a 35-year-old man. It’s not an offensive thing, it’s a little insulting, especially when I was a kid. To me, it’s like, how did that happen, how does that still happen, how do we keep doing it? It’s not like it’s over. We still think about representation, we still think about erasure or one-dimensional representation. This is a classic example, but it’s one example. Apu is grandfathered in. It’s like a fossil in nectar, you know what I mean? It’s a great example for us to see because it’s both then and now. Times have changed, but ultimately for me it wasn’t just about Apu. It’s really about where we are as a culture and the fact that racism isn’t a singular thing. It’s a virus. It mutates, and every era, it changes.

The film spiraled out of a bit you did a few years ago for Totally Biased With W. Kamau Bell. How did that come about?

I pitched the idea of doing the story [tied to the] Mindy Project premiere. He said I should do it, that it’d be more genuine.

Was that your first on-air segment?

That was my first one. I didn’t want to. I was like, This is Kamau’s show. I want to focus on him, as a writer. He was like, If you don’t do this I will fire you. I was like, Okay, you make a good point.

You’ve always been politically minded, and the question of Apu is about identity politics. But in general, do you feel pressure at all to talk about Indian stuff?

What I talk about onstage is what I want to talk about, it’s not like I’m thinking, This is the political angle. My first thought is, Who has the power in a situation and how are they using that power? I usually see myself as the person who has less power, so it’s natural to me that it’s observational more than it is political. But there is pressure at the end of the day.

Anything you wish you’d done differently with the film?

There’s this one anecdote we didn’t put in that kills me. I did some research, and Peter Sellers and Satyajit Ray knew each other [Editor’s note: Peter Sellers starred in The Party, in a role Hank Azaria has compared to Apu; Ray created The Apu Trilogy, the famous Bengali series that the Simpsons’ Apu got his name from.] Ray wanted Sellers to be in his first attempt for a film, called Alien. They hit it off. Then Ray saw Sellers in The Party and was horrified. I just met this man. This is what he thinks of me? And the voice he uses. Peter Sellers has a monkey pet in the movie. The monkey’s name is Apu, and that’s not a coincidence, especially during [the time of the release of Ray’s Apu Trilogy]. I hear that story and I think about Apu, the cartoon character. You take [Ray’s] main character and give him this voice you know he would hate. The fact that [Apu the monkey] wasn’t squashed — this is what happens when you don’t squash it. It doesn’t look the same way, but it still survived.

The casualness of those choices recalls the Dana Gould quote [in the Apu doc] about how it’s just funny — the Indian accent, that is.

I love the fact that Dana was so honest. People are like, How can you deal with Dana Gould being such a jerk? I’m like, he wasn’t a jerk. He was being honest. Do you want him to say sorry and move on? That’s not interesting.

That’s the great thing about the fossil quality of Apu. Yes it’s a fossil, but it’s a living fossil. You can access the people making it. They’re still in the business. Hank is still doing the voice.

It’s not enough to be simply aware that something is wrong. That Huffington Post piece that you’ve done [an article I wrote, in which Azaria commented on misgivings about Apu] — he was aware and still kept doing [the voice], kept doing it publicly. That’s so weird to me. A couple years after you and I did that interview [for the HuffPost story], they had Utkarsh [Ambudkar] on [to play Apu’s son]. To me, it was very much, Okay, we did our bit. We can keep doing Apu.

Did you hear the rumors that they were thinking of killing Apu off?

That’s lazy. If Apu dies, I’ll be the guy who killed Apu.

You wouldn’t be proud of that?

I’d feel mixed about it.

If he’s gonna do the voice, he’s gonna do the voice. Do I want a brown person doing it? I don’t want anyone to do the voice. If there’s some truth to the South Asian convenience-clerk trope, well, a lot of those people end up buying the business. How about we make him a small-business owner? He’s always an employee, subservient. Why don’t we get him an opportunity to own? His kids could be voiced by brown actors. There’s more creative solutions, but it’s easier to kill off the character than change. [Meanwhile] Smithers is out. It’s a cartoon. You can do whatever you want. It’s been 30 years. He’s been in the same place. Plus the show — it’s a little stale. That could give it a completely new angle.

Because what I love about The Simpsons is the creativity. That’s why Apu is so frustrating. It’s not creative, it’s hacky. Anybody could do that character. To kill him off is extremely lazy and a cop-out.

You’ve talked about not fitting into a “black-white binary” or Latino identity, which one could think of as the triad of American public identities. And I know in media there’s a sense, too, that East Asian or South Asian concerns are seen as secondary. A kind of, why do you have complaints? You’re not minorities — you’re just like white people. Or that using the language of the Civil Rights Movement or black actors is piggybacking, taking something that’s not yours. Is that an issue with the documentary? Do you have to justify even having problems, and figure out how to frame them?

I think it’s about how you explain your position. The importance of having Whoopi Goldberg [who appears in the film] is to talk about the larger legacy. I didn’t want something void of history. They’re going after brown people, but that’s not how this started. There’s a history of how people of color are used and how their bodies and images are monetized. Any South Asian in this country has faced it considerably easier [than black people]. When we talk about big moments, we talk about 9/11. You’re being held by law enforcement, seen as a threat. Black people deal with that every day. So it’s from this large legacy, but it’s not the same.

There are moments where I wish I were clearer because that’s important. To say, this is not the same. It’s part of the larger [story].

[At this point, a group of kids ran into the café where we were sitting, in Windsor Terrace, Brooklyn. It was Halloween, and they wanted candy.]

I grew up in Queens. This is what it was like. We had community. Not necessarily running into shops [for Halloween]; we had homes to go to. But this feels closer to home than other neighborhoods in Brooklyn.

I actually wanted to ask about your childhood.

Oh, yeah, I’m so sorry it couldn’t work out with my parents. [I’d hoped to interview Hari at his family home.] My dad had a heart procedure.

I’m so sorry to hear that.

It’s fine. He’s fine now. I mean, he’s an older South Asian man. He eats too much rice.

It comes for all of us. Speaking of South Asian, can you talk more about Queens? I have this magnetic pull to it, and am actually thinking about moving there.

Where would you go?

When I go, I go to Jackson Heights. [Where all the Indians live.]

If I’m going to go to Queens, not with my folks, I would go to Jackson Heights. It’s gentrifying. Put another brown face there. When I saw the Starbucks, I was like, This is not good. When I saw the indie coffee shop, I was like, This is the end.

Did you grow up there?

Until I was 9. Then we moved to Floral Park, Queens, which turned into a more suburban Little Asia.

Was it indian?

Lots of Malayalis. [Indians from Kerala]. You’re Telugu, right?

No I’m Kannadiga. Rao is common to both.

Were your people Telugu when they moved?

Actually, no. My mom’s family was Maharashtran at some point, before they became Kannadigas. My dad’s side is Tamilian, from Coimbatore.

It’s funny because if we talked to someone from the north, they’d be like, you’re the same. Where is Kannada spoken? Is that Bangalore?

Yep.

I did a gig there, when I toured India.

Is the documentary playing in India?

I hope so. If not, I don’t care if it’s bootlegged or not. I wish it weren’t, but I want people to see.

I’m already getting emails, messages from there, Europe. The reach of this film is massive. It’s a Simpsons movie above all else, and people love The Simpsons. It’s part of their childhoods, a huge influence. And no one has ever made a film critical of The Simpsons. This is the first. It’s also a little nerve-wracking to think about how I was going to deal with the [backlash] in comedy and Simpsons fans and people who hate anyone who doesn’t like something. That’s another reason why the whole Hank Azaria not participating thing annoys me. [Editor’s note: The film follows Kondabolu’s attempts to talk to the actor.] I put my butt on the line to do this at the end of the day. If you think it makes you look bad [not to talk], I think it looks better if you do.

The Dana Gould rule.

Dana Gould was gutsy. The doc would have been different if we had Hank. We had to use archival stuff instead.

I’m surprised because, with me, he wanted to talk about it. He sort of wanted to come clean.

We spoke on the phone. It’s not on the film because it was a private phone call. It’s public information, but we didn’t film it. I was geeking out. I’m a Simpsons fan, and here’s the voice of Mo, on the one hand.

What did he say?

He was like, “You’re really funny. I‘ve watched your stuff. What you’re doing is really great. But I’ve been involved in docs and I’m worried about throwing myself at the mercy of your edit.” The compromise is we do the interview done by Marc Maron or Terri Gross so I can’t screw with the edit. And I said yes because the film’s about accountability. He said he’d think about it. He gets back to me and he said no. That was the mail that I read in the movie. I’m like, what else can I do? I gave you the thing you said you’d need if you want to have an open discussion recorded by a third party. What else can I give you? At the end of the day, either he or Fox was against doing this project. I sympathize with him. It’s not an easy place to be in when you’ve played this character for so long and things change. But at the same time, you’re not 24. This isn’t your first job.

Even I get weirded out by how much things have changed sometimes. Like, how are we able to talk about his?

It’s crazy that no one ever said it was weird [before now]. No one even said, kind of.

A friend of mine, her theory about the minimizing of the Asian experience is that white people don’t want another group to feel bad about. Which I thought was interesting. How much can the culture apologize for? I think at some level there’s that.

That’s so selfish though. Who cares about apologies? Apologies don’t mean anything. It’s what can we do to make something better. It’s a public thing that influences a lot of people. Sure, there are some things as I’ve gotten older I’ve had to change and learn to understand. Gender, sexuality. Those are areas where I didn’t think critically when I was 15. But I never stopped learning. I always learned. That’s our responsibility as humans to try to listen and respect as much as possible where each other is at. I’m in the industry as well, and I have different pressures. I’m a stand-up and not necessarily as famous [as Azaria]. There’s a way to balance your professional responsibility and your growth at the end of the day. I hope we do have a conversation that allows us to talk about how come there aren’t more writers of color on staff, including on The Simpsons.

One of the most compelling arguments in favor of diversity — one of those words that can shut people’s minds off as soon as they hear it, because it feels like such a chore — is that it shouldn’t be a chore. The quality of creation gets better from an objective standpoint the more diverse the people dreaming it up. Like, do you want to be doing bad comedy or cutting-edge comedy?

This is boring to some degree to me and it is cutting edge to a lot of people. There’s a backlog. Chris Rock talked about this with Marc Maron, about his time on SNL. Even though the writers were incredible writers, they didn’t know how to write black [referential] comedy. When they had sketches of them they’d use these broad stereotypical images everybody knew. They only knew the hits, they had no subtlety, no understanding of the deeper repertoire.

The deep cuts of black culture. Whereas we know all the deep cuts for white people. We have to. I think that imbalance can be frustrating. I’ve had to study white people.

If I don’t study white people, I can’t understand anything. If I watch Can’t Hardly Wait and my first thought is — they’re white, I can’t enjoy this — then I can’t enjoy anything. Meanwhile, if there’s a lead or there’s one or two black characters, it’s a black show.

They have the option to experience a totally white culture. For us, it’s much harder to isolate yourself in that way.

For our survival, we have to make sure we don’t isolate ourselves. If we keep it to ourselves it’s going to make it difficult to make money or move forward.