This story originally ran in 2017, when Joss Whedon’s version of Justice League hit theaters. Since HBO Max’s new, much different Snyder Cut of Justice League now involves some of the Jack Kirby characters discussed below, we’re republishing it.”

“Y’know,” the late Jack Kirby told his assistant, Steve Sherman, “I’m competing against myself.” It was 1970, a little over three decades after Kirby stopped being Lower East Side street brawler Jacob Kurtzberg and became a professional writer-slash-artist under his percussive nom de plume. In that period, he had dreamt up much of the visual vocabulary and dramatis personae of the American comic book. His art style was explosive: foreshortened punches smacked into the reader’s eyeballs, and impossibly detailed sci-fi machinery littered his scenes. His genius for superhero storytelling was unparalleled: Along with Joe Simon, he had created Captain America in 1941; along with his frenemy Stan Lee and scattered others, he had spent the 1960s dreaming up stories that introduced and developed most of the Marvel pantheon, including the Avengers, the X-Men, the Fantastic Four, the Incredible Hulk, Nick Fury, Doctor Doom, Black Panther, and even the anthropomorphic tree-creature Groot.

But Sherman recalls the so-called King of Comics feeling dissatisfied at age 52. “I’m competing against myself because I did all these characters and stories,” Kirby mused, “and now I need to come up with something different.”

So he did. In that year, Kirby jumped ship from Marvel and made a much-ballyhooed arrival at its blood-rival, DC. “The word from high is — THE GREAT ONE IS COMING,” read the company’s house ads. “People! Places! Things! So powerful in concept — it’s almost terrifying!” When Kirby’s first DC issue finally debuted, the ads upped their verbiage: “Kirby is coming. Kirby is coming. Kirby’s coming? NO! He’s here … with his first BLOCKBUSTER!” In 1970 and 1971, the King took over one existing series and launched three new ones, all of them winding around a single grand narrative. That narrative bore an odd-but-memorable umbrella name: the Fourth World. No one in comics had tried its kind of storytelling technique before, and Kirby had never been given so much leeway to write and draw whatever he wanted. It told of a new pantheon of gods — some angelic, some fascistic — and was illustrated with vistas so wondrous that even Superman stared at them in awe.

It was the first great work of auteurism in superhero fiction. It was the biggest swing ever taken by history’s greatest superhero storyteller. And it became his most epic failure.

There were other Kirby efforts over the years that sold more poorly or were met with more critical derision, but none had such a yawning and humiliating gap between ambition and reality. Instead of leading readers to believe the hype it received at its launch, it was met with profoundly mixed reviews; instead of running for hundreds of issues, as Kirby had intended, it was canceled within three years. The unfinished status of the Fourth World is one of the great tragedies of comics. There was an ill-fated attempt at tacking on an ending in the mid-1980s but, by then, the momentum had been lost and Kirby’s original plans for a serialized graphic novel had been dashed. Nevertheless, the Fourth World has had a remarkable afterlife, popping up in DC stories with increasing frequency.

Now, it’s being enshrined on the big screen. This month’s Warner Bros. mega-tentpole, Justice League, centers on the mythos that Kirby built: Wonder Woman, Batman, and their cohort do battle with Fourth World villain Steppenwolf, his legion of frenzied Parademons, and looming in the background is those baddies’ ultimate overlord, the endlessly sinister Darkseid (pronounced “dark side” — Kirby had a fondness for off-kilter naming). Just as important, the movie’s MacGuffins are Mother Boxes, advanced devices that first came out of the King’s pen. The real-world story that began with Kirby trying to top himself at the dawn of the ’70s has reached a zenith. But the ride it took to get there was as bumpy as any in comics history.

The Fourth World may have been born, in part, out of frustration with this website’s parent publication, New York magazine. In 1966, while Kirby was working at Marvel, a reporter named Nat Freedland penned an article about the company for New York’s antecedent, the Sunday magazine of the New York Herald-Tribune. Writing about Marvel at the time was something of a no-brainer, as the company was in the ongoing process of revolutionizing superhero fiction and bringing it to a more mature audience. Kirby was more responsible for that than just about anybody, but the public perception was that the showmanlike Lee deserved the lion’s share of the accolades — in no small part because the comics’ credits didn’t bill Kirby as a co-writer, just as an artist. Freedland’s article spoke of how “Stan Lee dreamed up the ‘Marvel Age of Comics’ in 1961” and of “Lee’s vision to bring human reality into comic books,” while Kirby was described as secondary and resembling “the assistant foreman in a girdle factory.”

The publication of the piece was a watershed moment for Kirby. According to his biographer and assistant Mark Evanier, “Both men later recalled that the collaboration was never the same after that day, and it was more than just an injured ego at work.” Indeed, it was a matter of a professional creator receiving proper recognition for the sweat of his brow. Around the same time, Kirby was the prime mover on a Thor story about a prophecy of the end of the title character’s legion of Norse gods. It concluded with their home, Asgard, being destroyed in an explosive apocalypse, only to eventually be replaced by a new world of young deities. Kirby had ideas about stories featuring these new gods, but was reticent to tell them. Evanier tells me Kirby presented his concepts to Lee, “who said, in effect, ‘Yes, we want them,’ but [Lee] wanted to just fold them into existing comics; Jack would be expected to just give them away for the same deal he always had. No additional pay, no special credit.”* That didn’t sit well with Kirby. “He thought at that point, That’s too good of an idea to give them, the way they’re treating me,” recalls Evanier. Meanwhile, various other publishers tried to court Kirby, who may not have been primarily regarded as a Marvel writer but was widely regarded within the industry and fandom as the company’s finest artist. Never one to rest on such laurels, Kirby sought to impress these suitors with secret character designs for his gods, but he wasn’t satisfied with any of the offers he received in return. He remained at Marvel, glum but driven.

A surprise visit from an old friend changed that professional calculus and presented Kirby with the chance to fundamentally alter the way a superhero creator could operate. Seeking a new lease on life and better air quality for his asthmatic wife and youngest daughter, he had moved from his native New York to California in early 1969, and soon afterward, DC editorial director Carmine Infantino visited the Kirbys for a Passover seder. When the dining and prayers died down, Kirby brought Infantino to his office and showed off designs he’d drawn up for three potential comics series about his new gods. Infantino was awed and told Kirby he was game to bring the projects to DC. Kirby pondered the possibility while his dissatisfaction grew at Marvel — new ownership came in and presented him with a contract requiring him, among other stipulations, to give up any claims that he created the Marvel characters. That was it. Never again would he play the under-credited second fiddle. He took Sherman and Evanier out to lunch at Los Angeles’s Canter’s Deli in February of 1970 and laid it out for them: “I’ve made a deal,” he said. “I’m gonna leave Marvel for DC.”

“When he left Marvel and came to DC, it felt like Nixon going to China,” recalls historian and former DC publisher and president Paul Levitz, who was a fan, comics journalist, and freelance writer at the time. What the stunned baby-boomers who’d been spending the ’60s devouring Lee-Kirby collaborations didn’t know, was that this move wasn’t just about a creator hanging his shingle in a new spot. “He wanted to take comics further than they had gone,” says Sherman. “He had seen European comics that had come out in printed hardback editions and he wanted to do that. He wanted to do different stories.” He had also seen the contemporary love shown for J.R.R. Tolkien’s collected Lord of the Rings books (even though he himself hadn’t read them) and wanted to create a story in a similar format: individual installments eventually collected into a single epic, something that had never been tried in comics. Most of the story would be told in three ongoing series with delightfully hyperbolic names: The Forever People, Mister Miracle, and The New Gods. He was asked to take over an existing DC book, too, but didn’t want to steal steady work away from anyone, so he opted to do the low-selling Superman’s Pal Jimmy Olsen, which had no regular creative team. It, too, would be part of the nascent Fourth World. The story cycle began with issue 133 of that series, whose cover bore the publication date of October 1970 and the words “Kirby Is Here!” When you flipped it open you’d see on the first page that Kirby was billed as writer and artist. The lack of credit and recognition that haunted him at Marvel was banished.

But new curses appeared at DC right away. I ask Evanier when Kirby started to get frustrated with his new home and he replies, “I would say day two.” Some points of contention were small; others, large. Kirby found out that DC didn’t approve of the way he drew Superman and Jimmy Olsen’s faces, and they were redrawn against his will. Kirby didn’t actually want his saga to be a work of auteurism: he aimed to craft the first few stories, introduce his bevy of characters and notions, and then hand the titles off to Evanier, Sherman, and other creators to write and draw, with Kirby acting as an artistic overseer. DC, on the other hand, had invested in Kirby and wanted audiences to see the man in action, not stuff that he’d merely influenced. In Kirby’s vision, he would have gradually moved on to write and draw more series unrelated to his new gods and handed those off, too, but Infantino and the rest of the DC brass wanted to get as many new pieces of intellectual property (which they would own, but Kirby would at least be credited for creating) out of Kirby as quickly as they could, and pushed him to introduce new characters at a dizzying pace. Internal creative fervor and external corporate pressure made for a potent combination.

So it’s no wonder that the first few issues of Jimmy Olsen, The New Gods, The Forever People, and Mister Miracle are overwhelming reads today. In some cases, the avalanche of concepts leaves you scratching your head in confusion, most notably in Jimmy Olsen. On the very first page of that first chapter in the Fourth World (though it was not yet called that — the name didn’t pop up until it appeared on covers a few months later, and to this day, no one’s sure who came up with it), Supes’s sidekick walks into the garage of the Newsboy Legion. This must have been bizarre for the average reader at the time — the Legion were a Kirby-and-Simon–created group of kids who hung around with a superhero named the Guardian back in the 1940s, but who had barely appeared since then. And this wasn’t even the original Legion; it was their kids. Another brand-new character, media titan Morgan Edge, had sent Jimmy to accompany the Newsboys on a journey that introduces them to all kinds of new proper nouns. They go to some place called the Wild Area, where they run into long-haired bikers known as the Outsiders, who live in a giant wooden structure called Habitat, and who fear a giant truck known as the Mountain of Judgment. Soon, they all encounter a government initiative called the Project, which produces genetically engineered creatures called DNAliens (who were not actual aliens), and which has a rival operation run by evil (actual) aliens named Simyan and Mokkari. Oh, and Clark Kent gets hit by a car and a giant clone of Jimmy fights Superman and the Guardian. To make matters worse, Kirby had no ear for naturalistic dialogue: “Kill! Destroy! I have been programmed by the forces who created me, to eliminate whatever lies before me! You must die!” the Jimmy clone tells the Guardian, who replies, “Only if you prevail! But, you won’t! Not while there is strength in my body — and agility to compensate for your ponderous size!” It was a hard pill to swallow.

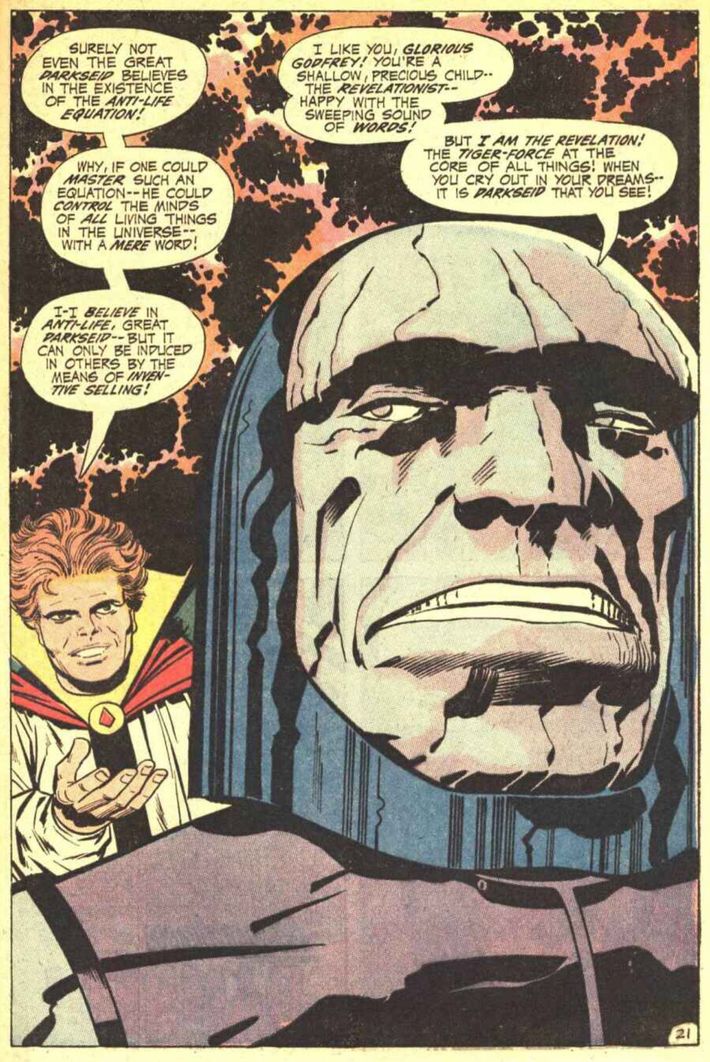

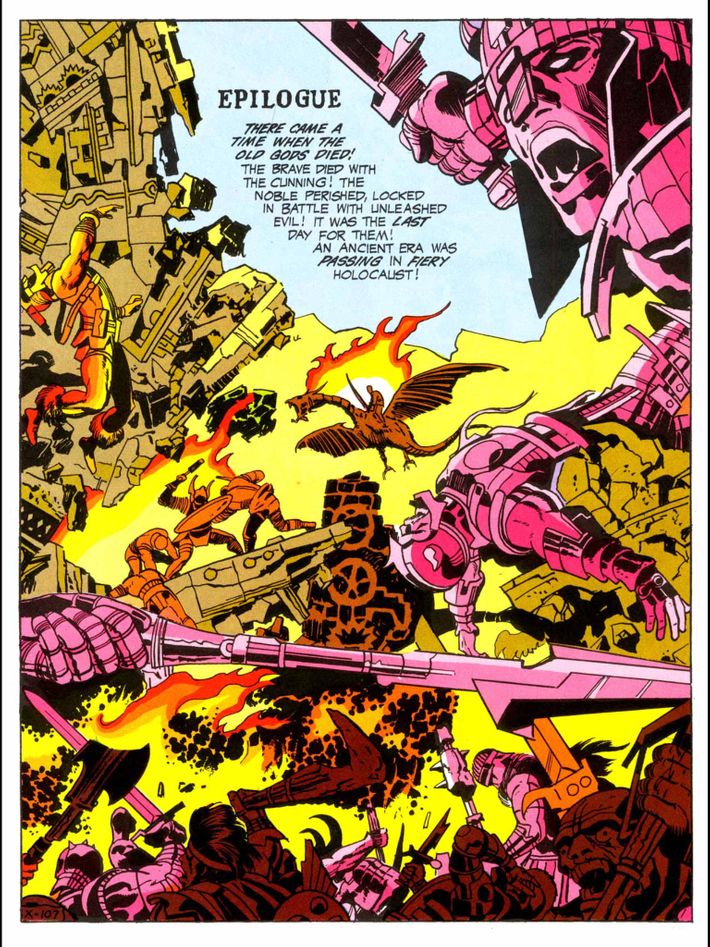

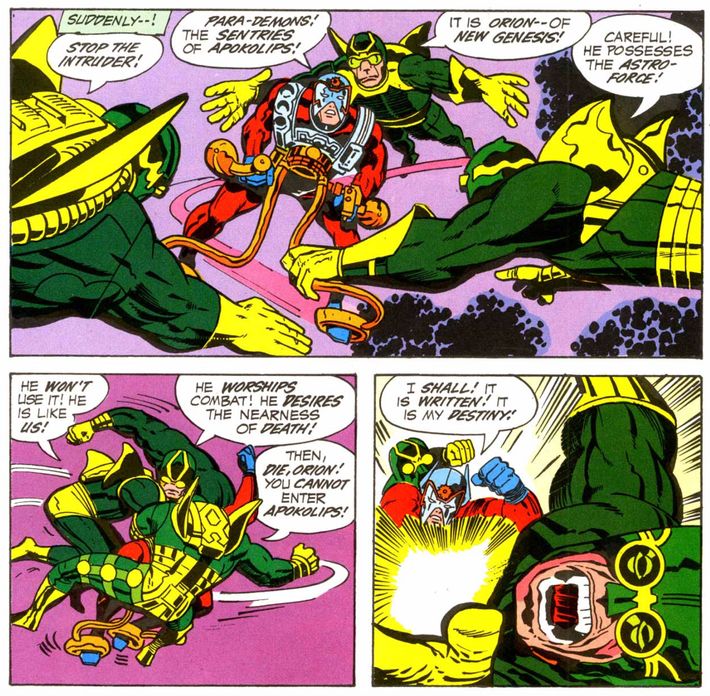

But the introductory issues were often stunning in their grandeur. There’s no better example than The New Gods No. 1, which has one of the all-time-great first pages. It consists of a single panel in which weapons, bodies, and buildings crumble in crackling flame, all rendered with Kirby’s signature surreal mechanistic detail. “EPILOGUE” is the curious opening word, followed by the nigh-Biblical announcement, “There came a time when the Old Gods died! The brave died with the cunning! The noble perished, locked in battle with unleashed evil! It was the last day for them! An ancient era was passing in fiery holocaust!” We soon learn that these mysterious Old Gods split their home world in two, leaving two “giant molten bodies, spinning slow and barren — clean of all that had gone before — adrift in the fading sounds of cosmic thunder.” Two new worlds were formed and populated by gods: heavenly New Genesis and satanic Apokolips. We meet the bitter, angry hero of New Genesis, Orion, and we see him travel to Apokolips and battle the shock troops known as the Parademons. Only in the final panel do we see the greatest character of the Fourth World, Apokoliptan dictator Darkseid, accompanied by a terrific tease for the tales to come: “PROLOGUE: As it was in the time of the Old Gods — the titanic struggle for the fate of mankind is to rage once again!! The New Gods wield greater power — for in our day, it’s we who live in the dark shadow of the outcome!” Kirby was a Jew with a firm belief in God, and this was the stuff of religion, barely contained by the comics page.

The other two series were just as ambitious and strange. The Forever People was Kirby’s tribute to the chilled-out youths of the just-gone ’60s, following a group of young New Gods who trip around Earth while running from Darkseid. Mister Miracle was at once the most straightforward and most odd: its title character, an Earth-based refugee from Apokolips, is a costumed superhero who fights a shifting cast of bad guys, but his unconventional shtick is that he’s an escape artist, constantly getting chained up or boxed in, only to bust out at the last minute. (His real name was Scott Free, har har.) He, the Forever People, and Orion all rely on handheld New Genesis machines known as Mother Boxes, which have wondrous and varied powers — it’s become a mundanity in comics criticism to point out that Kirby more or less predicted the iPhone. Reaction to this cavalcade of new and oft-bewildering stuff was, as you might expect, mixed. “Jack Kirby, writer, is as good as Jack Kirby, artist … In summary, may I say that you’ve got a great mag? Keep up the great work,” read a letter published in The New Gods No. 3. Alternatively, dig this line from a missive published in Jimmy Olsen No. 136: “Kirby’s artwork is very good, but the story about the Newsboy Legion was one of the worst things I’ve ever read! The ‘Wild Area’ bit was terrible, and Jimmy’s new attitude — especially toward Supie — is lousy.”

There are masterworks that were misunderstood in their own time and universally regarded as triumphs long afterward, but the Fourth World is not one of them. Debate over its merits rages on to this day, even among Kirby superfans. “I kind of appreciate the stories abstractly and I appreciate Jack’s creative vitality, but for me, that whole Fourth World series never coalesced into a coherent creative vision,” says Gary Groth, longtime publisher of The Comics Journal and diehard Kirby backer. “I think Jack, without the constraining influence of Stan, was almost too … I mean, he needed that constraining influence.” Novelist Jonathan Lethem concurred in an essay on Kirby: “At DC, Kirby seemed to have flown off into his own cosmic realms of superheroes and supervillains without any important human counterparts or identities. The feet of his work never touched the ground. The results were impressive, and quite boring.” That said, there are those in high creative places who swear by the stuff. “The New Gods and the Fourth World are landmark works,” writer Junot Díaz tells me, “and, whatever faults he had as a writer, his ideas are still being pilfered by everyone.” As novelist Michael Chabon, who first encountered Kirby in the ’70s, puts it to me, “He was clearly building this mythology overtly, by saying, ‘The old gods died and there arose the new gods.’ Just that sentence really captured my imagination, and I just loved that stuff so much. I became a confirmed Kirbyite.”

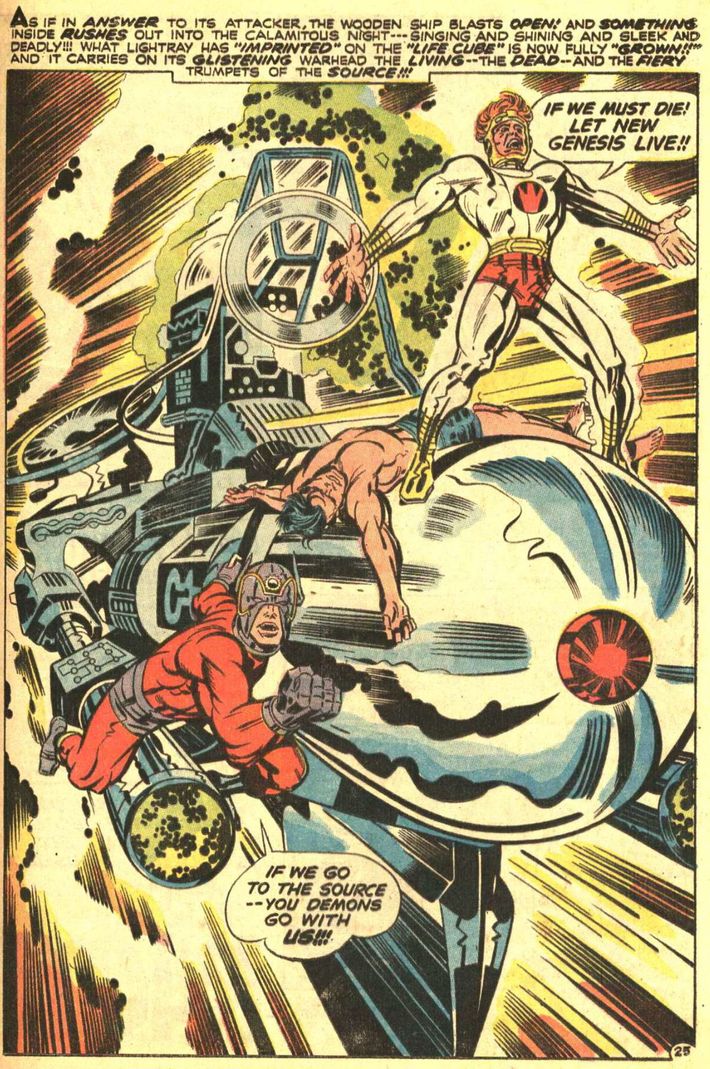

Chabon wasn’t the only one, and if you were won over by the early material, you were blown away by what came in the second stage of the saga. Once it became clear that there was no backup waiting to take over for him, Kirby had to embrace his role as an auteur and take a more passionate investment in the Fourth World stories. They reached their apogee in three consecutive issues of The New Gods, numbers six through eight. First came “The Glory Boat,” a story in which Orion and Lightray’s fight with some seaborne enemies takes a back seat to a philosophical duke-out between a human father and son over the merits of violence. Then “The Pact,” where we learn about the origins of the New Genesis/Apokolips conflict and Kirby grapples with the question of whether it’s worth treating an enemy with dignity during war. Finally, there was “The Death Wish of Terrible Turpin,” about an ordinary cop who resolutely refuses to back down or die in his effort to arrest both Orion and Kalibak as they fight in his city, thus proclaiming Kirby’s belief in the essential worthiness of every mortal human, so long as they held a moral code. Throughout those issues, you encountered artwork as good as any Kirby had ever produced, from the sweeping “Glory Boat” image image of Orion, Lightray, and the antiwar son exploding toward the reader on a massive projectile riddled with intricate Kirbyish circuitry; to the brutally scarred face and unyielding body language of Turpin as he refuses to give in to death. No one drew like Kirby, and Kirby never drew better.

It wasn’t enough for DC. Sales were fine, but Kirby was supposed to be better than fine. “They wanted it to really knock the block off Marvel when they got Jack,” Evanier recalls. DC was in dire need of a megahit, too — the comics industry was in a slump, and DC was hit especially hard after Marvel started undercutting them with a price decrease from 25 cents to 20. DC kept launching new series — not just Kirby’s — and abandoning them at the first sign that they might not explode, just so they could make room for the next attempt. DC begged Kirby to simplify his plots and do stunts like adding existing superhero Deadman to a few issues of The Forever People. A good company man, he tried to do as he was told, but it’s hard to streamline such Byzantine material, and his characters were so sui generis that they couldn’t mesh well with the rest of the DC universe. If the higher echelons of the company had fallen in love with the Fourth World, things might have been different, but no one seemed to get what was going on in the books. “I tried to read them,” DC editor Julius Schwartz was quoted as saying in Ronin Ro’s Kirby history Tales to Astonish. “Let’s put it this way: He was not nearly as good a writer as he was an artist.”

Oddly enough, the death knell for the Fourth World came partially as a result of Kirby being a victim of his own talents. DC asked him to come up with new character ideas and he generated a rhyming beast known as the Demon (according to Evanier, Kirby dreamed up the entire character’s gist and design over dinner one night) and a postapocalyptic boy adventurer named Kamandi. While Kirby was working on the 11th issue of The Forever People, Infantino called him to say DC was so excited about the new figures that they were “suspending” The Forever People and The New Gods. His run on Jimmy Olsen was to end, as well. Kirby went to tell Evanier and Sherman what had just happened. “It was one of the worst moments of his life that I ever witnessed,” Evanier recalls. “He was trembling. He looked like a guy who had been punched repeatedly in the face.” Kirby hadn’t had an exact plan for how the Fourth World would play out, and was famously given to improvisation, but he had certainly intended to have it last longer than 11-odd chapters per series. Mister Miracle was allowed to run until issue 18, but the stories were weak and sloppy. “A moment stirs! A moment lives! A moment passes on!” read narration in the final page of The Forever People. “Will they return someday? Destiny will answer this question, too!”

For the remainder of Kirby’s time at DC, destiny’s answer was mostly just, “No.” He dutifully did The Demon and Kamandi until they, too, were canceled. He did a short-lived series called O.M.A.C., short for “One Man Army Corps.” He did war stories. He did a single issue of a story about a barbarian warrior named Atlas. He revived an old Simon/Kirby character called the Sandman. His Kamandi run went 37 issues, but nothing else survived very long. There were murmurs about putting Kirby on a book about a staple character like Superman or Batman, but Evanier says the editors were wary about giving control to a creator 3,000 miles away from the DC offices. He was stuck. “The work he’d been doing for the last year or so of the ’70s DC deal was such a trivial use of such a major talent,” recalls Levitz, who by then had started working a low-level job at the publisher. “As an artist, he wasn’t being put on anything that made a difference. It didn’t feel like that could last.” Sure enough, it didn’t, and without much ceremony, Kirby reluctantly took an offer to go back to Marvel in 1975. He cranked out some work there until 1978, but it, too, failed to garner the kind of audience Kirby had commanded in his ’60s heyday. As Evanier puts it, “For the first time in his life, he was operating from a position of failure.”

But the failure wasn’t total or permanent. If you want to understand why the Fourth World has had such a lasting afterlife, you have to look to the reason it brought Kirby back to DC in the mid-’80s: the quality of its bad guys. By that point, Levitz was a senior official at the publisher. “We were doing a major new toy line and the DC mythology, particularly at that point in history, was fairly weak on villains,” he recalls. “So we came upon the idea of incorporating Darkseid and the Fourth World characters and came upon the idea that we could use that as a way to give Jack a taste.”

That taste he’s referring to was a sharing of revenue for the characters he created. Levitz and publisher Jenette Kahn reached out to the aging Kirby and asked him to do some revised character designs for various Fourth World characters for use in the toys, thus allowing him to share in the money brought in for their use there and elsewhere. They also invited him to create an ending to the Fourth World and the result was a shambolic 1985 graphic novel called The Hunger Dogs, which was beset by production issues and creative differences. No one was quite happy with it, but at least Kirby was able to put his once-heralded mythology to bed before he died in 1994. “Someday, New Gods will be a hit,” he said near the end of his life. “You’ll see.”

That was yet another example of Kirby seeing the future. Over the decades since the publication of The Hunger Dogs, the Fourth World has become one of the core DC texts in a broad range of mediums. What’s fascinating is that, unlike most such texts, the element that has had the sturdiest staying power isn’t superheroes like Orion or the Forever People. It’s Darkseid. He and sinister allies like Steppenwolf have popped up in DC’s comics events, cartoons, video games and, now, movies. The Fourth World is about mythic absolutes, and nothing in it was more absolute than the pure brutality of Darkseid and his ilk. To use a gaming metaphor, he became DC’s final boss: the antagonist you use when you want to trump everything that’s come before.

Even if there is no Fourth World movie anytime soon, the dreams Kirby dreamt in that short period at the dawn of the ’70s show no sign of disappearing. Right now, one of the most acclaimed comics on shelves is DC’s Mister Miracle revival, written and drawn by superstars Tom King and Mitch Gerads, respectively. King is well aware that the series’ antecedent is an uphill climb. “People ask me, ‘What do I need to read to prepare for your Mister Miracle?’” he tells me. “It would be nice if I could just say, ‘Go back and read the original Mister Miracle. But if you straight read it, it’s like sticking your head into the id of the country. It’s like you get drowned under the ideas of it. Jack Kirby’s writing is not the subtlety of Hemingway, it’s the scream of myth.”

King is doing a bang-up job interpreting that scream, but one can imagine Kirby being a little dissatisfied in the young man — not because of the quality of his intrepretation, but because he’s retreading old ground, however brilliantly. “Jack had very little respect for the kids who came to him and said, ‘I really want to write the Hulk’ or ‘I want to draw like you, Mr. Kirby,’” Evanier recalls. “He did not want people to imitate his style. He wanted them to imitate his way of thinking and to take it and do something new.” That was what Kirby, himself, tried to do with the Fourth World, and though it wouldn’t play out as he’d intended during his lifetime, its innovation has set a benchmark for creativity in the years that have followed. Kirby may have been competing with himself, but to this day, no one quite competes with Kirby.

*This article has been updated to reflect the fact that Kirby discussed his concepts for the New Gods with Lee.