At this point, so many films have depicted the assassination of John F. Kennedy that an enterprising editor with some time on her hands could probably cut and splice the various stagings together in a real-time 360-degree reenactment. Last year, we saw the infamous motorcade ride and the Air Force One swearing in through the eyes of Jackie Kennedy, in Pablo Larraín’s grief-stricken shriek of a film Jackie. That film dove into the personal abyss of a woman whose lifelong labor of appearances had been shattered, and offered very little in the way of reassurance. Rob Reiner’s LBJ, which also recounts the days leading up to and following the assassination, has the look and feel of something quite the opposite: a traditional, triumph-of-decency American fable, complete with mournful trumpet and distant military snare drums. Strangely, though, its title character is very nearly as emotionally unavailable as Natalie Portman’s Jackie, and the film’s takeaways just as hard to call “uplifting.” I’m just not sure the film realizes that.

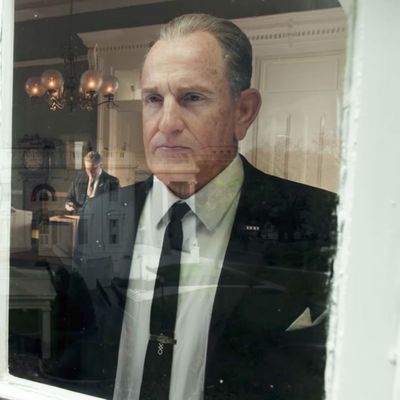

The first half of the film crosscuts between November 22, 1963, and the chain of events from Johnson’s 1960 presidential bid to his becoming Kennedy’s vice-president, and the party schism that led to the trip to Dallas. Johnson, played amiably by Woody Harrelson, is a generally liked 52-year-old Senate Majority Leader when the rising star Kennedy beats him in the primary. They clearly represent the past and future of the Democratic party, and Kennedy brings him into his administration as a means of keeping the old-timers on his side.

Johnson’s early defeat is one of the few character beats in LBJ that feels truly fresh, and not like a rehash of any number of ’90s presidential and military dramas. Here’s a man whose good-ol’-boy Texas bluster only barely masks a desperate need to be liked. Harrelson plays the moment with great emotional intelligence, a crack in a façade that has always been there, but is just now showing itself. But soon that need to be liked morphs into something a little more banal, and Johnson becomes an obstruction for Kennedy’s Civil Rights Act, always pumping the breaks, warning the president of all the feathers he stands to ruffle.

It’s not that Johnson isn’t a compelling dramatic figure, but Reiner’s film is too broad and simplistic to capture why that is. It feels like a film about a righteous hero whose time in the sun was a little later than he expected, but every one of Johnson’s good deeds come with a caveat. Even the film’s postscript, three title cards long, feels like it’s huffing and puffing to acknowledge Johnson’s shortcomings. So why make this movie, this way? Why now?

There’s something underwhelming and out of time in LBJ, down to the microaggression of watching Jennifer Jason Leigh, an actor enjoying a vibrant and memorable comeback this year, being on hand mostly to fetch sandwiches for her husband. The film’s final speech, given by Johnson on the senate floor to announce that he will be moving forward with the Civil Rights Act, and passionately advocating for a better quality of life for people of color, is given to a room without a brown person in sight. Of course, this is all historically accurate, but it’s hard to feel victorious about it, particularly with our 2017 hindsight about how glacial the change has been for the most vulnerable people in society. LBJ is a story about how the legitimacy of the rights of the disenfranchised weren’t an action item until one morally average man decided they were an action item. And there’s a movie there, but it’s not this respectful, retro thing Reiner has created. It’s a pitch-black satire.