About 23 minutes into Now, Voyager comes one of the most resplendent transformations in all of cinema.

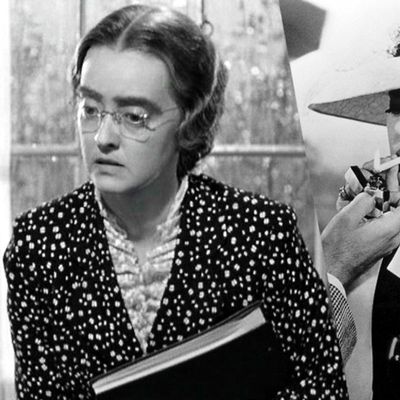

Charlotte Vale (played with trademark intensity and brutal grace by Bette Davis) begins the film as an archetypal spinster figure. Her eyebrows are unruly, clothes dowdy, and a definitive air of anxiety cloaks her. She comes across as an exposed nerve. But at that 23-minute mark, Charlotte is transformed. When the camera tilts upward to her luminescent face, half-shrouded by her hat, sheÔÇÖs glamorous and beautiful in ways she hadnÔÇÖt been before. The change isnÔÇÖt just cosmetic. ItÔÇÖs a reflection of an interior transformation thatÔÇÖs still in progress ÔÇö thanks to an extended stay in a sanitarium ÔÇö from a mentally strained spinster to a woman charting her own path.

In the years since its release, the film has garnered a reputation as DavisÔÇÖs best performance and a quintessential example of the womenÔÇÖs picture, a proto-feminist subgenre that took shape in 1930s Hollywood that made the interior lives of complex women its terrain. When I watched the 1942 film ÔÇö which celebrates its 75th anniversary this year ÔÇö for the first time as a teenager, it wasnÔÇÖt the glamour or even the stirring romance that captured my imagination. It was the knotted story about CharlotteÔÇÖs struggle with mental illness that I was drawn to because it offered something I hadnÔÇÖt seen before or since in cinematic madwomen: hope.

Today, Now, Voyager remains a timeless portrait of a woman who pulls herself back from the edge of madness to create a life sheÔÇÖs proud to live, with the help of both psychiatry and her own willpower. The film is buttressed by sleek, highly efficient Hollywood production and the moving performances of the cast, notably Davis and Claude Rains as Dr. Jaquith, who helps usher Charlotte into this next phase of her life. Most poignantly, Now, Voyager is a curious outlier in the pantheon of American cinema that concerns itself with women living with mental illness. Few films offer the kind of blistering hope and empathy that has made Now, Voyager endure.

Films featuring mentally ill characters ÔÇö consider Glenn CloseÔÇÖs maniacal portrayal in Fatal Attraction, Angelina JolieÔÇÖs charismatic turn in Girl, Interrupted, and the hothouse women of Tennessee Williams adaptations ÔÇö often treat these women with emotional distance. Their contorting faces and bodies are a spectacle, while the particulars of their mind remain opaque. It would be difficult to cover all the permutations of madwomen, but they often fall into a few categories: cautionary true-life tales (Sylvia; The Three Faces of Eve), deliriously fun vixens who give way to toxicity and violence (Girl, Interrupted; The Craft; Fatal Attraction), vehicles for brutalization (A Streetcar Named Desire), and women in horror films (Black Swan being a notable recent addition to the canon). Others slink through noir, like the overheated Technicolor Leave Her to Heaven and sharp The Dark Mirror. This is a pantheon of women whose aches and ailments, desires and downfalls I have been studying for years ÔÇö partially out of need. Through most of my life grappling with mental illness, I have had no friends or family who, at least openly, dealt with similar issues. So I turned to the screen to find communion. While I personally love many of these films, and the performances that anchor them, I am acutely aware that in almost all of these cases, female madness is a tool, an archetype, a symbol. To be branded mad as a woman can sometimes feel like a black mark you canÔÇÖt escape from that allows people to disregard your voice and personhood. This is a culture that film often perpetuates through its bloodthirsty femme fatales and treacly biopics offering saccharine endings in which madness is swept away by the love of a good man. Rarely are these women seen as people with interior lives.

Based on the novel by Olive Higgins Prouty, Now, Voyager centers on Charlotte Vale (Davis), a repressed spinster and only daughter of a prominent Boston family, whose life is brutally controlled by her aristocratic mother, Mrs. Windie Vale (Gladys Cooper). Mrs. Vale heaps emotional abuse upon her daughter to such a degree, Charlotte is perpetually on the edge of a nervous breakdown. Her sister-in-law, Lisa (Ilka Chase), intervenes by introducing Charlotte to Dr. Jaquith (Rains), a wryly humorous and caring psychiatrist whose sanitarium becomes a haven for the young woman. The filmÔÇÖs legacy is often tied to its tender romanticism: the moving yet doomed relationship between Charlotte and the married Jeremiah ÔÇ£JerryÔÇØ Durrance (Paul Henreid). But what truly makes Now, Voyager memorable is how it centers on CharlotteÔÇÖs interior life, including her mental illness, above all else, and how Davis capably brings this to life.

DavisÔÇÖs reputation as an actress is that of unmatched intensity. She consistently played women who make shirking societal rules into an art form ÔÇö martyrs, bold Southern belles, villainesses, city dwellers fueled by blinding anger. Charlotte Vale proves how deftly subtle and quiet Davis could be, despite her reputation for histrionics. Now, Voyager came relatively early in DavisÔÇÖs five-decade-long career, but by this point, Davis already had a total of five Academy Award nominations and one win. Now, Voyager would be her sixth. She had also earned a reputation among directors, reportedly including Irving Rapper, who directed Now, Voyager, as being difficult, exerting her own vision to shape the films she worked on. These same traits that directors and studio heads despised in Davis ÔÇö a dedication to her characters, an auteur-tinged streak, an interest in emotional and physical authenticity when bringing characters to life, no matter how repellent that may be ÔÇö are the very reasons that her performance as Charlotte Vale remains so potent. WhatÔÇÖs extraordinary about watching Davis in this role is her deft communication of CharlotteÔÇÖs interior life through her physicality ÔÇö the rigidity of her back as she walks, nervous hand-wringing, her wet saucer eyes darting across the room as if looking for an exit, and the startling grace and directness that comes after her transformation. She begins the film as taut as piano wire, ready to snap; by the end, sheÔÇÖs softened into a languid repose. There are still flashes of that intensity ÔÇö like in the moving final scene ÔÇö but now her energy is channeled gracefully and toward better targets. The rich emotional life Davis weaves for Charlotte, bringing nuance to even the smallest moments, is just one reason Now, Voyager is such a powerful narrative about mental illness. Ultimately, the empathy is woven into the story itself.

Now, Voyager was adapted for the screen by Casey Robinson and had a lot of material to work with, thanks to the original novel. Prouty was a pioneer for how she considered psychotherapy in her own work, eschewing the typical imagery of controlling, even malevolent doctors eager to perform lobotomies or circumscribe the lives of the women in their care, a trope that gets particular use in horror. WhatÔÇÖs fascinating is how Dr. Jaquith forgoes the usual Freudian touches that defined cinematic representations of such doctors at the time, focusing instead on ideas of self-acceptance.

ProutyÔÇÖs careful consideration of mental health and psychiatry, and the filmÔÇÖs portrayal of it, would feel stirring even if released today. But in the early 1940s, it was radical. As mental-health activist Darby Penney and psychiatrist Peter Stastny write about one victim of trauma in the 2009 book The Lives They Left Behind, which explores the stories of people institutionalized in the Willard Psychiatric Center during the 20th century: ÔÇ£Throughout history, violence and loss have sometimes driven women mad. Psychiatry has been generally complicit in this process. Today, a woman like Ethel Small who enters the system at least has a chance that she might be asked ÔÇÿWhat happened to you?ÔÇÖ rather than ÔÇÿWhatÔÇÖs wrong with you?ÔÇÖ In certain places, she might even be referred to a specialist who has experience working with trauma survivors. But in the 1930s, a woman beaten by her husband and mourning her children would not have been considered a trauma survivor.ÔÇØ In real life and its cinematic reflections, women struggling with trauma and mental-health concerns were rarely granted the interiority and care they deserved. Now, Voyager is unique in that it understands the links between CharlotteÔÇÖs mental duress and her motherÔÇÖs abuse above all else; furthermore, it shows the possibility of overcoming traumas, not being consumed by them.

Charlotte may have a level of privilege and access that makes getting care for her illness easier. But how she navigates that care is strikingly familiar. In watching the film, IÔÇÖm reminded of something a psychiatrist told me the second time I was institutionalized at 17: ÔÇ£For you, medication will only do 10 percent. The rest, the hard work, is up to you.ÔÇØ I didnÔÇÖt truly understand what he meant at the time. But as I grew older and was forced to navigate tragedies without a support system, I came to understand how precarious mental health can be. Now, Voyager forces Charlotte to consistently reconsider how she wants to live, whether sheÔÇÖs navigating her motherÔÇÖs attempts to manipulate her life or Dr. JaquithÔÇÖs tender probing into the sides of herself she keeps hidden. At every point, itÔÇÖs CharlotteÔÇÖs understanding of herself that informs its visual landscape, mood, and approach to mental illness. What Now, Voyager ultimately demonstrates is that mental-illness narratives need not be unerringly realistic but resolutely human to work.

Charlotte Vale and I are separated by race and class, culture and access. But in my late teens, shuffling between mental hospitals and new medications, Now, Voyager gave me what I couldnÔÇÖt find in reality ÔÇö the reality of chilly mental-hospital halls, the shameful gaze of my mother, the tender embrace of my brother trying to calm me down when I sought new ways to hurt myself: the ability to be seen and even understood.

Mental illness is complex. Hope is often withheld. Empathetic treatment can sometimes feel like a fantasy. For me, Now, Voyager offered a spark of motivation and hope, the ability to imagine a future for myself when I was too poor to get therapy and too depressed to leave my bed. It was a small joy I held on to in dark times, a salve, a form of self-care. This is how a film can save your life.