This review originally ran during TIFF.

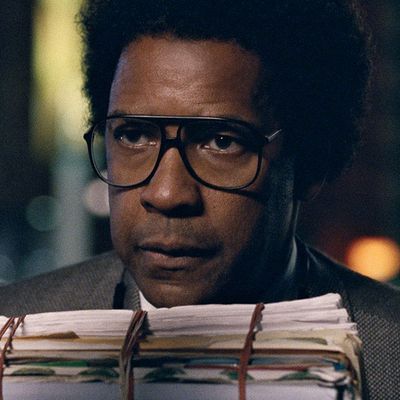

In the ethical drama Roman J. Israel, Esq., Denzel Washington plays an activist lawyer on the spectrum (Washington used the now-unfashionable word Asperger’s at the Toronto International Film Festival premiere), and the film has been shaped around his character’s every stammer and awkward, dissociative glance. There’s no one else of consequence onscreen: It’s all Denzel all the time. One of Washington’s specialties is cocky fast talk, so it’s like watching a great pitcher take something off his fastball, his wobblers somehow finding the plate. And it’s enjoyable seeing him dig into the mind-set of a man who finds injustice and inequality everywhere and tenaciously clings to the identity (and Afro and wardrobe) he had in the 1960s and ’70s, even when his manner alienates clients, prosecutors, and judges. Roman’s tics and obliviousness to social cues make the legal system seem even less responsive — further beyond the reach of the little guy.

Writer-director Dan Gilroy’s first film was the crawly melodrama Nightcrawler, and although his protagonist in Roman J. Israel, Esq. is vastly different, Gilroy has the same theme: corruption. A man who has worked diligently in the shadows for little money, recognition, or gratitude finds a morally bankrupt way of getting richer quick and likes having power for the first time — or at least for the first time in 40 years.

Roman — who knows every case and statute in the book by heart — has for years been the “man behind the curtain” for his flamboyant and beloved partner. Then that partner has a stroke and Roman has to enter the “white man’s courtroom.” In his first time before a judge in decades, he gets a $5,000 fine for contempt. What galls Roman — what he has dedicated his life to fighting — is the prosecutorial strategy of overcharging an accused (generally indigent) criminal so that he or she will feel pressured to take a lesser plea, the resulting sentence the same as if the defendant had gone to trial with the appropriate charge and lost. That’s a form of blackmail, of course, and Roman wants nothing less than to make new law. “Each of us is greater than the worst thing we’ve ever done,” he says. Throwing kids in prison for long sentences all but guarantees that the worst thing they’ve ever done will define them for life.

The change comes when, in a peculiar but exciting turn, the impoverished Roman takes a job at a tony L.A. firm run by Colin Farrell as a former student of Roman’s partner. The lawyer, George, is creepily sleek in his made-to-measure suits and appears to have little social conscience. But he thinks Roman’s “savant” tendencies will be of use to him. And maybe George does have a social conscience. Maybe. Hard to tell. Farrell has chosen to make his face a complete blank, either because the plotting is too obvious (if Roman doesn’t sensitize him, there’s no drama) or because he knows Washington will be the focus of every scene no matter what he does. It’s a very strange, estranged performance. Nice suits, though.

What Roman does to change his fortunes is a terrific piece of plotting — wrong but not too wrong (the psycho in Nightcrawler made the world a worse place) and for ends that could be seen as valid. Then Roman tells himself he deserves having money and not having to suffer insults or illegal construction outside his rundown apartment building (which the city persistently ignores).

This is a formula movie but Gilroy is no hack. He hits the expected beats but with more color and depth than you expect. The legal issues seem thought-through. And he comes up with a doozy of a twist, which leads to a sharp, vise-tightening final act. James Newton Howard’s score is an urban concerto with a shiver of jazz.

But all one’s little quibbles with the plot accumulate. Gilroy half gets away with the character of the young, ingenuous progressive who looks past Roman’s oddball demeanor and wants to drink in his idealism, but only because Carmen Ejogo is so winning. (A love interest? The idea is teased, although she looks 30 years younger at least.) The lack of supporting characters of stature really hurts. The drama is muted because Roman never really goes to the Dark Side: Washington wears his guilty conscience like a shroud, and whenever he glances at the photo of ’60s activist Bayard Rustin in his apartment, you think he’s going to cry.

I saw the ending coming about ten minutes beforehand and quietly prayed it wouldn’t be what I feared. The climax is ludicrous and the dénouement unforgivably corny — it’s everything that many of us liked the movie for not being. What diminishes Roman J. Israel, Esq. is the same thing that holds you: Denzel’s magnetism. The problem with too powerful a magnet is that it pulls stuff off the tables and walls and leaves everything out of whack.