The kidnapping drama All the Money in the World is an elaborate demonstration of the idea that the very rich are not like you and me ÔÇö and also that the oil magnate J. Paul Getty was barking mad. In 1973, when the movie is set, the octogenarian billionaire was regarded as the wealthiest man in the history of the world. He was also an infamous skinflint who installed a pay phone for his guests at his baronial English mansion. The film centers on GettyÔÇÖs apparent indifference to the life of his 16-year-old grandson and namesake, Paul III, kidnapped by Italian radicals who would, after several months, sell the boy to the Mafia. Getty was adamant in refusing to pay ransom or even to discuss the matter with his daughter-in-law Gail, who was divorced from GettyÔÇÖs alcoholic, drug-addicted son, Paul II, and had no funds of her own. The kidnappersÔÇÖ spokesman ÔÇö who phoned her regularly with demands and threats ÔÇö was actually more courteous to her than was her billionaire former father-in-law.

ItÔÇÖs impossible to divorce the film itself from its offscreen drama, which also turns on the abuse of wealth and privilege. As soon as the floodgates opened on stories of Kevin SpaceyÔÇÖs alleged sexual predations, the director, Ridley Scott, made the unprecedented decision to expunge all traces of SpaceyÔÇÖs Getty Sr. from what was an essentially finished film and replace him with (the more age-appropriate) Christopher Plummer. YouÔÇÖll want to know whether the seams show, and the answer is they donÔÇÖt, at all. But that shouldnÔÇÖt be a surprise. GettyÔÇÖs scenes are discrete entities ÔÇö heÔÇÖs not directly involved in the main suspense plot. And even normal films involve outlandish artifice. Because of shooting schedules, an actor entering a doorway might well come out of it six weeks later on a different continent. The only hint of Spacey I could discern was in PlummerÔÇÖs readings. The lines were clearly shaped for SpaceyÔÇÖs icy, sneering intonations. His malevolent poltergeist hovers.

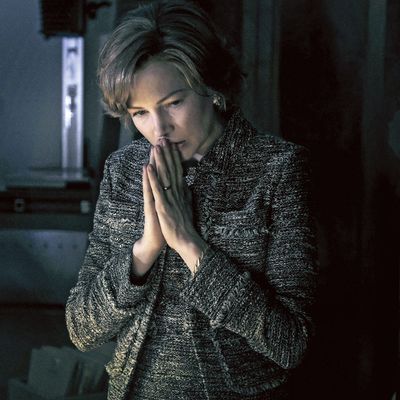

My guess is that there was one overriding factor in ScottÔÇÖs decision to rebuild sets and summon back his actors: The fear that SpaceyÔÇÖs presence would distract the world (which includes Oscar voters) from the marvelous performance of Michelle Williams as Gail. ItÔÇÖs a real transformation.

IÔÇÖve never heard this diction from her before ÔÇö sharp, with a hint of North Shore (i.e., old money) Long Island and perhaps a Kennedy or two. (The real Gail grew up in San Francisco but was well acquainted with the cadences of the East Coast rich.) Through the tension in her body and intensity of her voice, Williams conveys not just the terror of losing a son but the tragic absurdity of bearing the illustrious name Getty when family ties confer zero power. After Gail, desperate, attempts to sell a valuable gift from Getty Sr. given to her son, Williams sags to the stairs outside an Italian art museum and canÔÇÖt seem to settle on laughing or weeping. Her expression crystallizes the entire bizarre story.

The film needs her. Working from John PearsonÔÇÖs Getty-family saga, screenwriter David Scarpa adds a couple of shoot-outs that never happened and eliminates some fascinating nuances ÔÇö one of which was the elder GettyÔÇÖs terror of the Italian Mafia. The movieÔÇÖs Paul III is too much of a cipher. (I suspect scenes were cut.) The more disappointing change is in the nature of GettyÔÇÖs top security consultant, Fletcher Chace, whom the billionaire finally brought in to negotiate for the best possible deal (i.e., one that would involve no money). In PearsonÔÇÖs telling, Chace cocked things up, not only deducing that the kidnapping was contrived by the boy himself but also going to bed with a woman who turned out to be a carabinieri spy. The movie portrays some of ChaceÔÇÖs lapses but doesnÔÇÖt milk them for mordant effect; and, as played by the reliably stolid Mark Wahlberg, heÔÇÖs not the wild card youÔÇÖd hope for. Wahlberg has a gentle presence, though, and partners well with Williams. But WilliamsÔÇÖs true counterweight is the French actor Romain Duris as the Italian kidnapper who calls himself ÔÇ£CinquantaÔÇØ and shows an unpredictable mix of decency and business sense. (Trouble is not his business.) Duris almost brings off the suspenseful but ridiculous climax ÔÇö which is laughable not because it didnÔÇÖt happen in life but because it happens all the time in dumb kidnapping melodramas.

How is Plummer? Crafty, as he usually is. Sixty years ago, when he was a randy sexual adventurer and troublemaker (he confesses as much in his entertaining autobiography), he could hardly have dreamed hed be the venerable, wholesome alternative to an alleged predator. But J. Paul Getty  an avid philanderer  is right in his wheelhouse. Plummer knows how to segue from whimsical theatricality in long shot to dead-eyed mendacity in close-up. Holding forth on the immortal beauty and escalating value of art and sculpture in contrast to the instability of people, he suggests both the clarity and tragedy of Gettys tunnel vision. All the money in the world  to buy a life in a vacuum that corroded his soul.

*This article appears in the December 25, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.