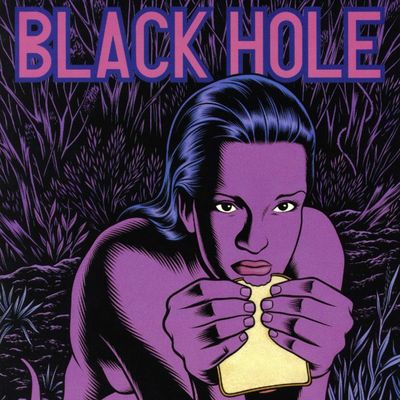

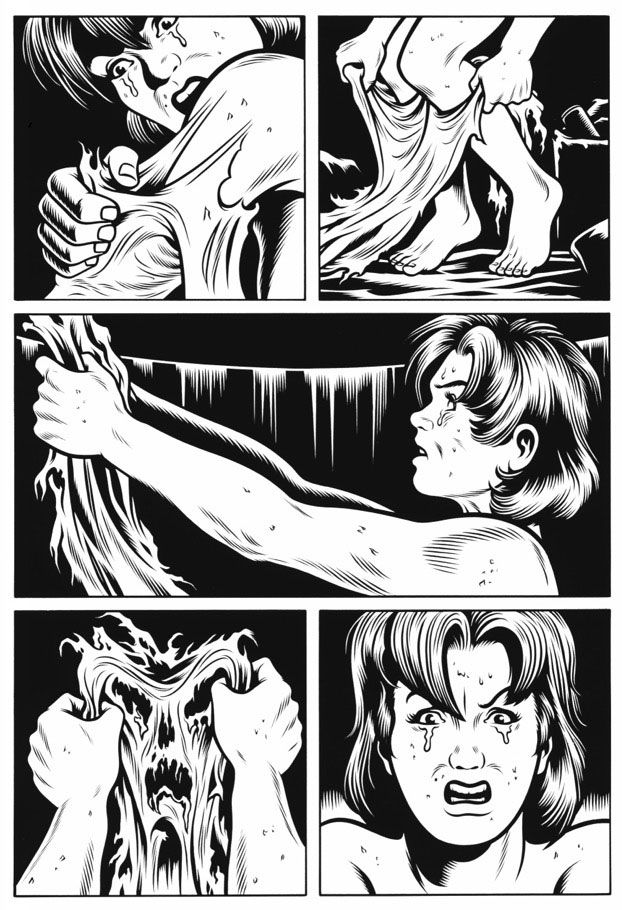

A handful of comics have made it into the canon of respectable modern literature, but none of them are as jarring as Charles Burns’s Black Hole. First published as a serialized story from 1995 to 2005, it’s a grim tale about doomed love and the outbreak of an STD that gives its victims hideous deformities. When Burns began it, his stark chiaroscuro and thick, wood-block-esque line work were already staples of the alternative-comics scene, but it represented a huge leap forward for his talents and fame. In the 12 years since Pantheon first collected the issues into a single volume, Black Hole has come to be a staple on lists of comics for people who are skeptical about comics, as well as syllabi for lit classes. Now, more than two decades after it began, portions of Black Hole have been reissued in an oversize “studio edition” from Fantagraphics that features scans of Burns’s original, unadulterated pages. We caught up with Burns to talk about the book’s legacy, how he sees it as more of a romance than a horror story, and whether or not The Simpsons’ Mr. Burns is named after him.

This is an odd question, but I promise I’m going somewhere with it. Do you watch Riverdale, that dark Archie Comics teen drama? Has that crossed your radar?

No, no it hasn’t.

I ask because I interviewed one of the stars, Cole Sprouse, who plays Jughead, and asked him what fictional works he thought the show was similar to. He responded by saying something along the lines of, “Oh, well, definitely Charles Burns’s Black Hole.”

[Laughs.] That’s funny. There’s just something about the name “Jughead,” which just made me laugh. Anyway, I think I’ve read about it, maybe some article about it, but I’ve never watched it. It just hasn’t crossed my radar, as you said.

Your influence spreads far and wide, is what I’m trying to say.

That’s funny. Jughead is taking it seriously.

Why do this studio-edition reprint? What was the impetus behind it?

The impetus behind it was pretty much I’ve got a flat file that’s still filled with my originals, and I look at it periodically. There’s something about just the size, and the scale, and the look that I still enjoy. I got in touch with Eric Reynolds at Fantagraphics, because I realized they were doing a similar size-scaled book of Jaime Hernandez’s work. I just asked if they were interested.

That’s surprising — I sorta figured it was an idea on the publisher’s side. How often do you go back and revisit Black Hole?

Actually, not that often. It’s one of those things where, like I said, it’s a huge flat file that’s sitting in a room. I’m rolling open the drawers, because I never remember which place to search for our origins. It’s something that I see stacked in there. So yeah. I don’t think … I haven’t … I don’t know when the last time I reread the actual book. It’s been a while. I think when I got the book of the Fantagraphics edition, I sat and read through a few chapters.

What did you make of it when you were rereading it? What was that experience like?

Looking at it in this scale, sitting on a tabletop, it seemed a little like experiencing, closer, for me to actually making the artwork. There’s a closer kind of connection, I guess, of just how it looks and feels, and the scale. It’s interesting in that it’s bound to a big giant book that’s hard to read.

Were there any moments of going, Dammit, I wish I could change this detail?

There’s plenty of that. At some point, you can spend your life fixing everything. Which I do spend a lot of time fixing things. But most of it, I just let go. I’m trying to think if there’s anything that was glaring. I told friends that sometimes, I look at a figure and it looks embarrassingly weird. They didn’t see it, but I saw it. It was glaringly obvious to me, but you kinda have to find that balance of getting it right and/or getting it right enough. You’ll spin your wheels forever.

Let’s jump back in time a little bit. What were the earliest origins of Black Hole? What were the first seedlings that got planted?

I was doing some shorter stories that kinda dealt with the whole idea of a disease or plague, this kind of teen plague. The idea was kinda bouncing around in my head for a while. For a while, I had a syndicated weekly comic strip, and I had a story that kind of touches on that whole idea of the plague, or teenagers with some disease that’s manifesting itself. I think it was just something that I realized I had been contemplating, thinking about, and wanted to get into it, and dig deeper.

One thing that strikes me in looking at the timeline of your work is how much of a sharp turn Black Hole represented for you in a number of regards. What did you want to do with Black Hole that you hadn’t done with previous comics?

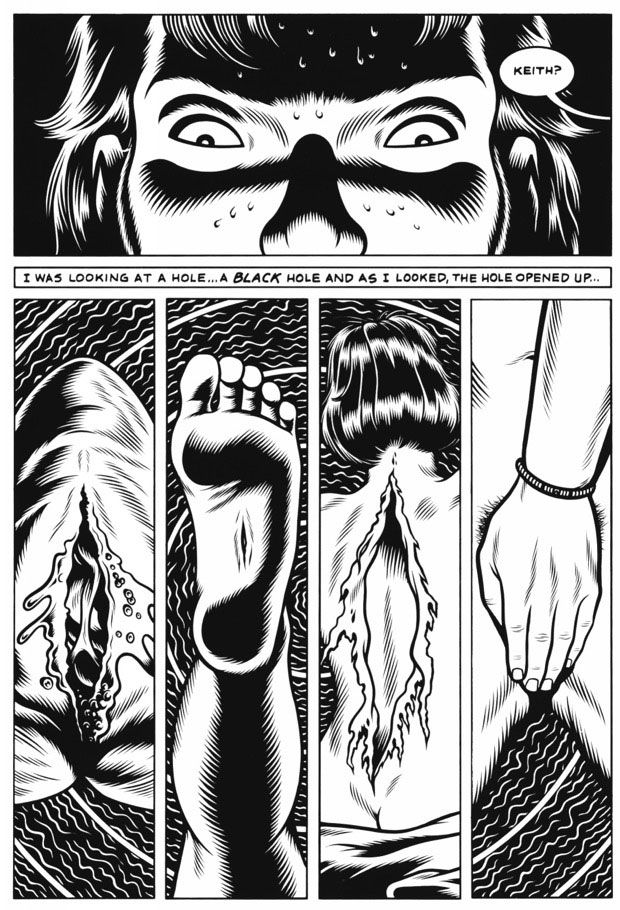

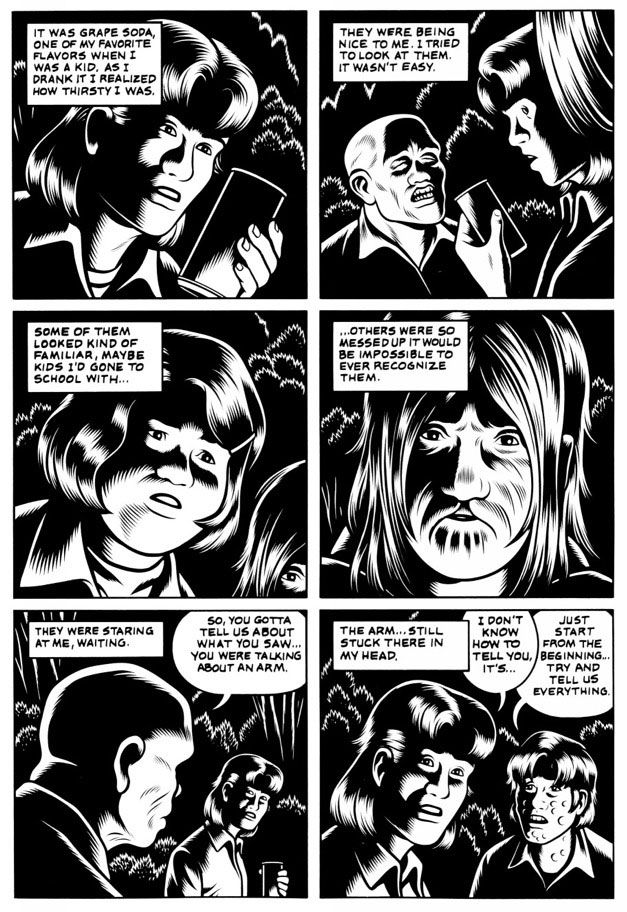

It probably looks a little less cartoony. I wasn’t trying for realism, per se, but I was trying to dig deeper into the characters, or the idea of focusing much more on the actual characters, as opposed to an idea. A lot of my earlier work had to do much more with the plot, but not so much the interior world of the characters. I think that was my focus: concentrating on that.

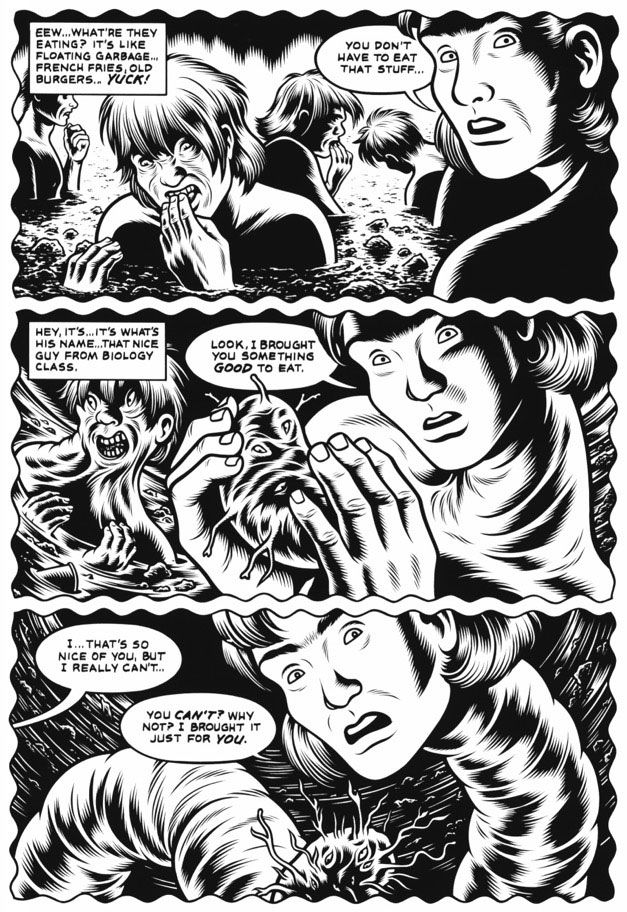

In rereading it, I was once again taken aback — as everyone is — by your mastery of the gross. You capture disgusting images very evocatively. Were you fascinated by gross stuff as a kid?

I guess so. I guess in an abstract sorta way. I wasn’t a kid that wanted to look at, I don’t know, autopsy photos or anything like that. It’s not something I can look at. I’ve had people show me photos like, “Oh, you’ll love looking at this,” and I don’t know, it’s some horrible dental surgery photo. I’m like, “No, you’re missing it. That’s not what I’m interested in.” I don’t know where that came from. I’m not really sure. I guess I wasn’t a kid that was interested in gross things, per se, but there was an attraction to some sort of darker world. I’m not coming up with a good answer for you on this one.

No, no, you’re doing great. Black Hole also has a lot of moments that almost feel like romance comics of the ’50s and ’60s. Did you read those at a formative age? They were a little before your time, I guess.

This sounds weird, but as an adult, I looked at romance comics. There’s something about them that’s fun to read. Usually they’re pretty bad stories, but at least on a surface level, they’re kinda fun to read. I think of Black Hole more of a romance comic than a horror comic. That’s my take.

I agree 1,000 percent. More often than not, the characters, like those in romance comics, are motivated by lust, passion, and jealousy. Or, at least, that’s my interpretation. Speaking of interpretation: Is it weird to know that Black Hole is taught in college literature classes?

It is really strange, to tell the truth. I’ve met enough people who tell me, “Oh, I teach that in my literature class,” or whatever class that happens to be. My daughter was at the Cleveland Art Institute, way back, and Black Hole was on the list of books that they were supposed to read, and she did not want to read it. As far as I know, she still has not read it.

Your daughter’s never read Black Hole?

I have two daughters. My eldest daughter read it, and my younger daughter opted for letting that go, which is fine by me.

Fine by you? That sounds like a betrayal of one’s father, to me!

I don’t know. It’s some pretty explicit imagery and ideas, and I don’t know, maybe she doesn’t want to associate that with her dad, so that’s fine with me.

What did the older one think of it?

It’s something I haven’t questioned, or I haven’t discussed that much. It’s kinda like, “Yeah I read it,” and then we kinda moved on, I guess. It’s an odd thing, to talk about all these things.

Did you gravitate toward any superhero comics as a kid?

I moved around and was always interested in comics and kinda searching those things out. You had limited resources. There’s X amount of comic you could either afford or had access to. Very early on, the first kind of superhero-y sorts of comics would be Batman and Superman, and the things that were just more readily available. Later, by the time I was, I don’t know, maybe like in fifth grade or sixth grade, I lived in Seattle. I would go down and I would search out Spider-Man and things like that. You kinda looked at everything on the rack and you made a decision of what you wanted to read. I had access to black-and-white reproductions of MAD comics, when it was actually a comic. Those really had, visually, a real impact on me. There were some spooky-looking black-and-white artwork. But yeah, if I had to choose between Superman and Batman, it would be Batman, because Batman looked darker and creepier.

You then discovered underground comix. What was the first one that made an impact on you?

Early on, you would go to the head shop, and there weren’t that many available. There was a sudden boom of them after a certain point, but early on, it was Zap. It was Robert Crumb’s early issues of Zap. Those probably had the biggest impact on me.

When you say they had an impact, how did that manifest itself? Did your drawing style change?

Oh yeah, sure. It was one of those things. With comics especially, I think you start as an artist primarily by copying things at first, or emulating the things that you enjoy or respond to.

I don’t wanna psychoanalyze too much, but you’ve spoken in the past about how high school was a rough period for you. Was reading comics an escape from hell?

That’s a good question. I think the place that I probably escaped to was through drawing. That was a way that I could focus. Obviously, I was reading things as well, and they had an influence. But as far as a real escape, I would say that was through drawing at that point. It’s an odd thing to be in that part of your life, and spending that many hours sitting at a table working on something, or focused on something that way. That was mine.

So you went to Evergreen State College alongside The Simpsons creator Matt Groening. I’ve heard rumors that Mr. Burns is named after you. I want to clear that up, once and for all. Is it true, or an urban legend?

It’s an urban legend, I guess. Yeah, there’s nothing conclusive. Sometimes I’ll answer it, and I’ll say, “Oh yes, it definitely is,” but no. I knew Matt, and he was the editor for a semester while I was working at the paper there. I think that he jokes about it as well. I saw him talking with Lynda Barry at some point, and someone asked that question. His answer was, “You’ll have to talk to my lawyers about that.” He was playing along with it as well. Maybe it was just kind of the subliminal sort of, I don’t know, lost memory of his of remembering that I was sitting there pasting up ads in the newspaper office. Who knows?

What did you learn in art school at UC-Davis? Did it transform you at all?

Not really. It didn’t transform me, I was there to do fine art. I think it was more having a period of time that I could experiment and try anything out. I knew it was a time that I could step out of what I had usually been doing, which was, I think, my focus was drawing. I did sculpture and photography, and I did some paintings and bad performance videos. [Laughs.] I think probably it was more being around a community of artists, and talking to people, and that had more of an impact on me than anything else.

I’m going to fanboy out a little bit here and ask what it was like to work with Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly in the early days of Raw. Did you guys have a feeling like you were on the cutting edge, or was it just another day at the office?

I’m trying to think of the best way to explain it. For me, meeting them and working on the magazine was really a very important early part of my life as a cartoonist. It was kinda meeting someone who understood what I was trying to do, and also just seeing who they were putting in the magazine. It was kinda like, Oh here’s proof of what I’ve always thought would be a great idea of a magazine. My first impression of the magazine was I didn’t love every single piece in there, but I loved the idea of what that looked like as a physical object: oversized and having weird little booklets stapled in there. There’s something about that that really left a very strong impression on me. I think what was really important was being introduced to a lot of amazing cartoonists. Whether they would be in the United States or people that they brought in from Europe, Spain, Italy, France, and all over the world, that had a huge impact.

With Black Hole, when did it become clear to you that this thing was a bigger deal than your previous work?

Well, first it was serialized and Fantagraphics put it out as a comic. I can’t remember how many issues they would sell, but it wasn’t a huge amount. It wasn’t suddenly this huge phenomenon. I think it was after everything got collected into a book that it started to have that kind of impact. That was my sense. Earlier, if you knew where to look, you’d go to a specialty comic-book store and find it. If that wasn’t your world, or something that you weren’t searching things out, you didn’t find it. There’s a lot of folks that say they had never read comics before, and this was their first comic. They discovered it in a [non-comics] bookstore, and just picked it up because it looked interesting, and then realized it was a long comic. Personally, I think it was once it was published as a hardbound book that it seemed like it had some kind of impact.

Why did the initial collection publish with Pantheon instead of Fantagraphics?

It was just a matter of wanting to give it its best chance for getting it out in the world, and promotion, and all those things, getting into bookstores, and all that. That was my take at the time.

I want to ask you about symbolism in general. In the more abstract moments of Black Hole, did you have specific meanings for the various cryptic words and images? You don’t have to tell me what the meanings were, I just want to know if they had meanings in your head, or if they were more instinctual.

I think it was both those things. There were certainly things that were instinctual, just like, Pay attention to this, because this image keeps on cropping up in my head. I think there’s also very specific things that a reader can interpret the way they want, but I certainly had very distinct ideas about what they represented, when I was thinking.

The series took about a decade to complete. When you started with your notebooks and sketchbooks, did you know what the last page would look like?

Probably not right at the beginning, but I had a core idea. I knew what that last page was gonna be for, let’s say, seven years. At the very beginning, we’re floundering around trying to find a way in to tell the story, and to tell it the way that feels right. There’s a lot of missteps. I did maybe three pages of like a first version, and I was writing it and drawing in the way that I had kinda worked previously, and I realized I had to step away from that.

Three pages of the last issue, you mean?

No, I’m sorry. When I was just starting out, when I was starting out with the idea. I was kinda working in a way that I was used to with the way I was telling the story, and the way that I was drawing, and the way everything was kind of unfolding. I realized that it was not gonna work that way, and I kinda pushed myself in another direction, and that somehow worked.

You’ve said in the past that creating can be a bit of a painful process for you.

Mm-hmm.

How painful was it to create a given issue of Black Hole?

It’s usually a pretty good sign if it’s a struggle. That usually means you’re working hard and digging in. On the rare occasions when I’ll put out a notebook from that period, it’s just that I construe a real struggle. Once it’s drawn, it somehow just seems concrete in my brain, there it is. Until you’re holding that physical object, that book in your hand, it’s not done. It’s hard to place myself back in that time period, I feel like another person now.

I guess it’s been 20-odd years since you started it.

[Groans.] Oh.

Sorry.

“Audibly groaning.” Write that down.

How long did you initially think it was gonna take you to the do the whole project?

I think I was hoping for working on it faster. I think it started out with trying to get out at least two issues a year, and it ended up being one a year, or one every ten months or something like that. It took as long as it had to take. It was always a matter of kinda balancing working on a comic, which was took a huge amount of time, and energy and focus, doing that, and having other paying jobs, doing illustration work and things like that. It was a balancing act of doing that. At least half my time was spent working on other projects as well.

You’ve said, in the past, that you contemplated doing the script for a movie adaption of Black Hole. Why didn’t you go ahead and complete one?

Did I say that? God, I sure don’t remember. I think that it’s just in a much more theoretical basis. I don’t know where I was going with that. I’ve written scripts before, of things that haven’t been made into movies or TV shows. I scripted that weird Dog-Boy thing that was on MTV years and years ago. Turned into a very odd final product.

That’s the best kind of final product, really.

Yes.

Did you ever communicate with Neil Gaiman about the Black Hole script he worked on?

No, all the back and forth always was just through an agent or a producer or something like that. There was never any direct contact, as far as I was concerned.

Black Hole is filled with people who are motivated by fear. What scares you? What keeps you up at night?

Oh my God. What keeps me up at night? Everything. All this adds up by saying I take sleeping pills, how’s that?

Oh dear.

That was kind of dramatic sounding, but I sure couldn’t be specific.

That’s fine.

The physical world is fearful, I’m afraid of the physical world. How’s that? All-inclusive.

That works. What do you when you need to chill out and relax? What’s sort of a happy thing you do to get into that zone?

You’re asking really difficult questions now. I walk. That’s something I do to relax, and get out of that space of sitting in studio. Walking helps.

What’s an average day for you these days? Are you in the studio everyday?

Pretty much, I hate to say that, but yeah pretty much. That doesn’t mean that I can work nonstop. It’s trying to work and trying to focus, and trying to get things done, so yeah, pretty much that. Get up early, go out for a walk, get in the studio, take a lot of breaks.

What’s the wildest theory that someone’s told you about the meaning of Black Hole?

Nothing too extreme. I think a lot of the story’s open-ended enough. The end of the book is fairly open, and I’ve had people explain to me that it’s very clear that there’s a suicide in the end of the book, but that’s not how I see it, so that’s extreme.

Well, thank you for taking the time to speak with me.

Sure. I hope you have something. I’m not one that’s … I think I’m also out of habit of doing interviews. It’s been a while. But anyway, it’s like, Yeah, Black Hole, yeah, I remember that book. I’ve got some vague memory of that. Sure, ask away.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.