It’s been a strange year for Hollywood (to say the least), full of resistance and revelations. Still, the industry is determined to celebrate — and this week we look at a few of the performances, directors, achievements, and, in one case, prosthetic jowls most likely to be honored.

In 2016, makeup artist Kazuhiro Tsuji received an email from Gary Oldman. The two men had met when Oldman was considering signing on to Tim Burton’s Planet of the Apes remake, which would have necessitated Tsuji turning him into a gigantic monkey. (Tim Roth took the part instead.) Now, Oldman had another transformation in mind: He was going to become Winston Churchill for Joe Wright’s Darkest Hour, and Tsuji was the only person he wanted to do his makeup. If Tsuji declined, the actor said, he wasn’t going to take the role.

Oldman wasn’t lying. “Me doing this was partly contingent on getting Kazuhiro,” he told Vulture. “One of the reasons I wanted Kazu was he was really one of the only people on the planet who could pull it off.”

The challenges were apparent. There are many things in this world that resemble Winston Churchill — babies, pugs, surely somewhere there’s a very lucky apricot — but Gary Oldman is not among them. “They don’t look like each other at all,” Tsuji said. “The proportions of the face, the placement of the eyes and nose and mouth, if they are close to each other it’s easy to make him look like Churchill. But it’s almost totally opposite. Churchill’s eyes are buggy and farther apart, Gary’s eyes are deep-set and close to each other.” That, Tsuji said sadly, is “impossible to change.” There are many things a makeup artist can do, but even they must bow to the limits of the human skull.

And there was another factor to consider: Tsuji had spent ten years trying to get out of the movie business, which he found emotionally unhealthy. He’d finally succeeded, and was enjoying his new life as a visual artist. Now Oldman was trying to pull him away. “It’s almost like a relationship,” he said, laughing. “I feel like I’m cheating.”

Tsuji did the mental calculus. It was an honor for Oldman to come to him with the job. The actor had long wanted to play Churchill; he and Tsuji had first discussed the idea years earlier, when Oldman had been circling another biopic of the prime minister. If he turned the job down, Oldman might never get the chance. Or the actor might decide to go with another makeup artist, and they might do a horrible job.

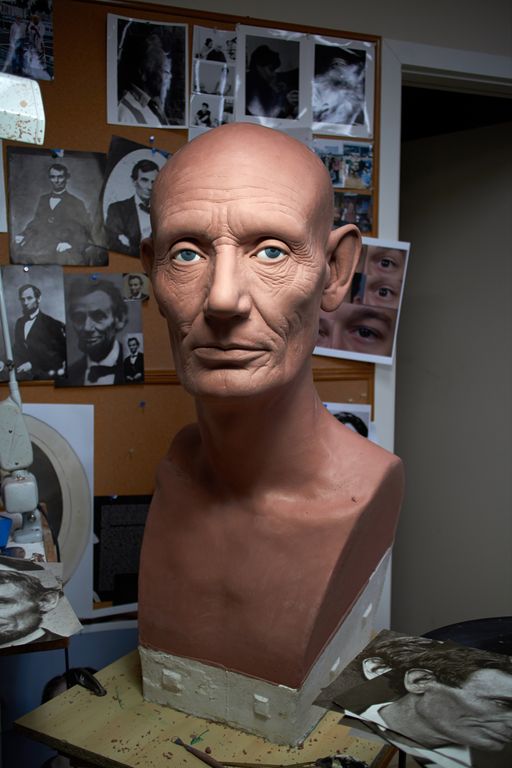

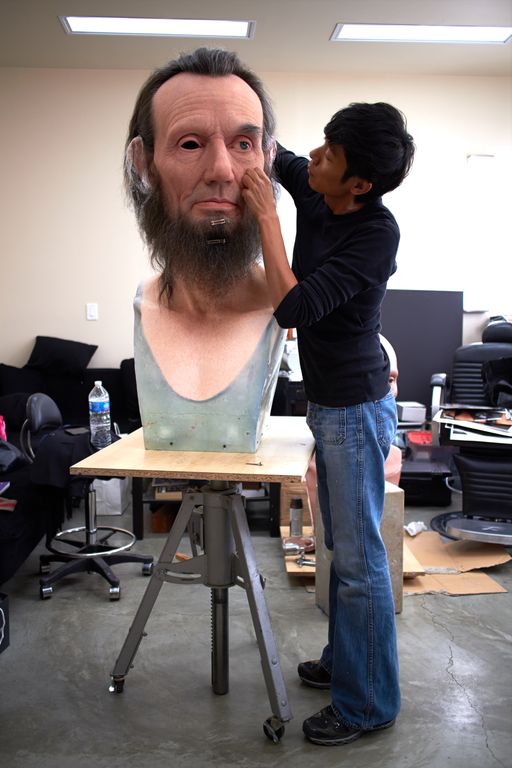

He also remembered the image that made him want to work in movies: As a teenager in Japan, he’d seen an image in Fangoria magazine of legendary makeup artist Dick Smith turning Hal Holbrook into Abraham Lincoln. ”All my career I wanted to do this kind of job, but it rarely happened,” he said. He was in.

Tsuji grew up in Kyoto. He did not have a happy childhood: He says his father was an alcoholic, and his mother was abusive. He spent a lot of time alone, drawing, sculpting, and catching insects. “Kyoto is kind of a strange place,” he said. “People pretend like, Oh, we have no problems and make a good face, but behind it there’s a lot of issues. I was confused by it and I had a hard time trusting anyone.”

After seeing the photo in Fangoria, Tsuji started his own experiments with special-effects makeup, using plaster, dental stone, foam latex, clay — “whatever I could grab.” He was his own model; sometimes he’d try to make himself Abraham Lincoln, others an old man. After a few months of tests, Tsuji happened to find Dick Smith’s PO box in the back of a magazine and soon the Japanese teenager and the Oscar-winning makeup artist struck up a correspondence. When Tsuji sent over photos of his latest attempts, Smith would send back critiques. “His advice was that there’s no good school out there right now,” Tsuji said. “The best school is to practice yourself.”

By chance, Smith was set to visit Tokyo as an adviser for the Japanese horror film Sweet Home. He helped Tsuji get a job in the makeup department, making molds of scars and dead bodies. On Sweet Home, Tsuji also met another young artist, Eddie Yang, who would turn out to be his entry into America. By now it was the 1990s, Japan’s Lost Decade, and Tsuji had left the failing Japanese film industry for a gig teaching makeup at the Yoyogi Animation Institute. The money was more reliable than the direct-to-video jobs he’d been working, but he felt he’d given up on his dreams. Yang, meanwhile, was working for Smith’s old protégé Rick Baker, who’d made his own name on Star Wars and An American Werewolf in London. “I made a phone call to Eddie,” Tsuiji said. “I told him, ‘I’m going to move to Hollywood and I need you to help me get a job.’” Baker was staffing up in advance of Men in Black, and Tsuji came highly recommended. He got the job, a visa, and an illegal sublet in a giant warehouse. “In Japan, if we had $10,000 and a month, that would be amazing,” Tsuji said. “In Los Angeles, we had six months to prepare one movie and a few million dollars to do the job.” He had arrived.

It was on Men in Black that Tsuji had his first breakthrough. He was helping Baker with Vincent D’Onofrio’s character, Edgar, whose corpse is used as a suit by a malevolent interstellar cockroach. In Baker’s design, Edgar’s skin would be like a burlap sack that slowly fell apart over the course of the film. It called for a certain softness and transparency that foam latex, the industry’s usual material, couldn’t quite manage. “Everybody was eager to find a new material,” Tsuji recalled. Gelatin broke down in heat; urethane rubber was harmful to skin. Silicone was semitransparent, resilient, and safe to use, but it had its own issues: It only came in two varieties, hard (really stiff, doesn’t move with the face) and soft (almost a liquid, can’t support its own shape). Tsuji came up with the idea of covering soft silicone in a thin skin of hard silicone, “basically a bag of gel.” It worked — when D’Onofrio turned in a characteristically twitchy performance, his new face twitched with him.

Tsuji didn’t do the on-set application on Men in Black. For that, you have to be in the union, which he was for 1999’s Life. (Martin Lawrence wrote a letter.) He discovered that the promotion meant lots of human interaction, often with actors who were not thrilled to be spending hours in the makeup chair.

Production on How the Grinch Stole Christmas was not easy for Jim Carrey. He was encased head-to-toe in green fur, in a design that kept changing, and the fake snow on set kept getting into the gigantic contacts he was forced to wear. The way Tsuji tells it, he took these frustrations out on the crew. “Once we were on set, he was really mean to everybody and at the beginning of the production they couldn’t finish,” he said. “After two weeks we only could finish three days’ worth of shooting schedule, because suddenly he would just disappear and when he came back, everything was ripped apart. We couldn’t shoot anything.” (According to his publicist, Carrey was unavailable for comment, but he once told the L.A. Times that making The Grinch was “a real lesson in Zen.”) One day was particularly terrible. “In the makeup trailer he just suddenly stands up and looks in the mirror, and pointing on his chin, he goes, ‘This color is different from what you did yesterday.’ I was using the same color I used yesterday. He says, ‘Fix it.’ And okay, you know, I ‘fixed’ it. Every day was like that.” Mentally exhausted, Tsuji met with Baker and one of the producers, who were also unhappy with the slow pace. They came up with a solution: He would go away for a while, which would make Carrey see how valuable he was. After a week of hiding, Carrey called. Tsuji didn’t answer, and he didn’t call back. Then director Ron Howard called. He left a message saying Carrey had sworn to change.

“I went back under one condition,” Tsuji said. “I was talking with my friends, and they all told me, ‘You should ask for a raise before you go back.’ I didn’t want to do that — kind of nasty. Then I got the idea: How about I ask them to help me to get a green card?” He returned, and Carrey kept his temper in check the rest of the shoot. The filmmakers wrote Tsuji letters of recommendation for the green card, though it took him winning the BAFTA for his work on The Grinch — the most attention the ceremony has ever received in America — for his application to get approved.

Tsuji sees that movie as a turning point: He started seeing a therapist afterward, and it made him realize how unhappy he was on set. “I’m really an introvert,” he said. “I don’t like to be in many groups of people, or work under those conditions.” Makeup artists have to be some of the first ones on set in the morning and the last ones to leave at night. They work constantly in between doing touch-ups, so 16-hour days are not unusual. “And the anxiety of what could happen in the next moment — maybe the actor freaks out or changes their mind — always being ready for it.” He remembers thinking: If I had a choice, I would not be in this mental state all the time.

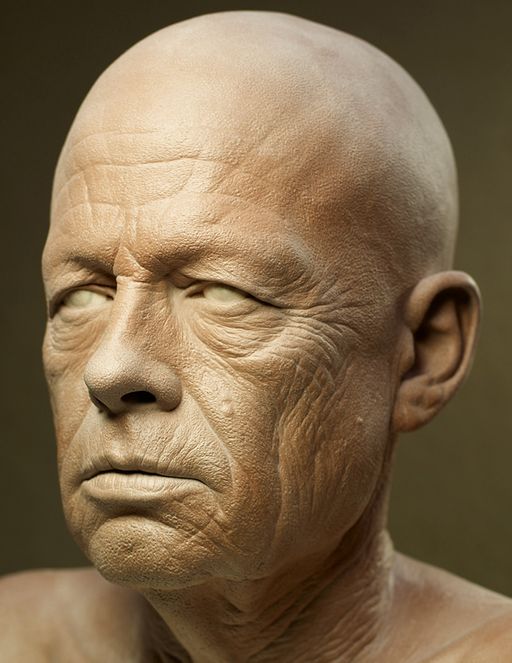

He knew he needed to leave the movie business. By coincidence, Dick Smith’s 80th birthday was approaching, and Tsuji had decided to honor his mentor with a hyperrealistic sculpture, two times life-size. “After I finished that portrait, I showed it to Dick and he was really touched,” he said. “He was literally crying.” Art suddenly seemed like another career option, but the film industry is full of people who have other good career options.

“I know many people who complain about the film industry but they cannot get out,” Tsuji said. “And I realize why it’s so hard to get out. Because in a way it’s almost guaranteed. If you are good, there will be a job that comes in and you make plenty of money and everything will be provided for you. Everyone treats you like a special person if you work in the film industry. When you travel and stay in a good hotel and fly in business class, you know, that becomes normal.”

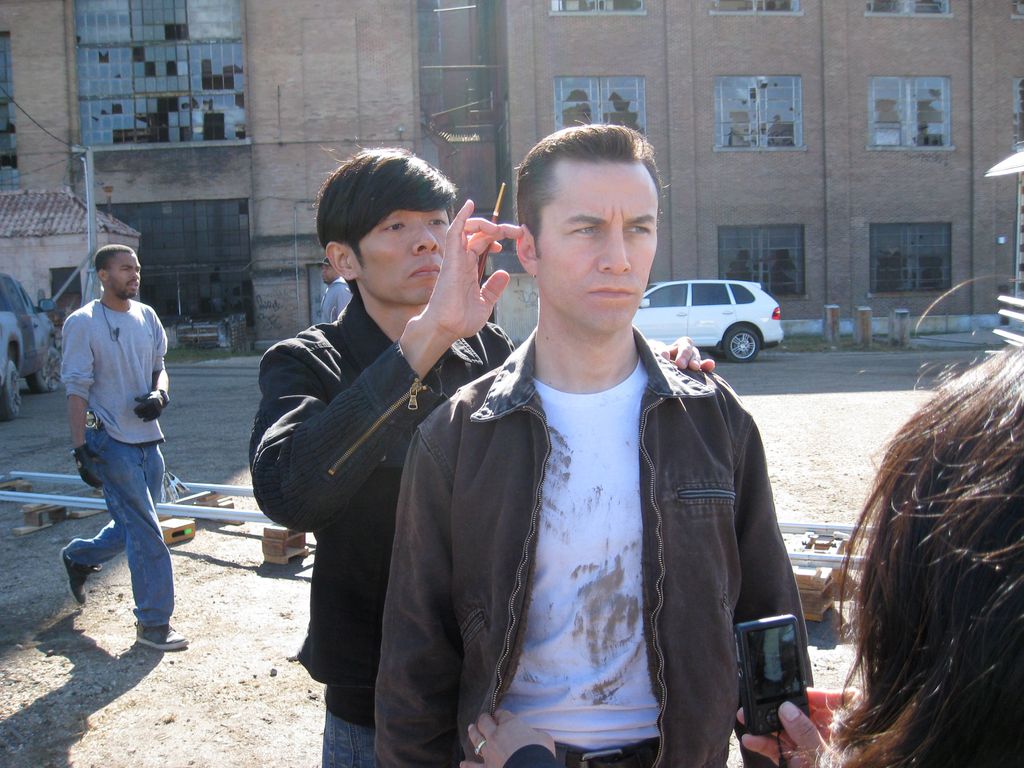

So he kept working. He turned Tim Roth into a monkey for Planet of the Apes. (He remembers Baker asking the filmmakers to cast actors with small noses, so of course “they ended up with the actor with the biggest nose in Hollywood.”) He created a silicone model that was the basis for the CGI elderly Brad Pitt in Benjamin Button. And, in his last film before making the jump, he transformed Joseph Gordon-Levitt into a young Bruce Willis in Looper. Though his work on that film was widely praised, Tsuji remains ambivalent about it. “I told them it’s not going to work because it’s just impossible,” he said. “I turned it down once and they came back to me. I told them, as long as you pay for it and you can accept that I cannot guarantee the outcome, I will do the design.” Willis famously won’t spend more than ten minutes in a makeup chair, and so instead of meeting in the middle with the two men’s faces, Tsuji had to make Gordon-Levitt into somebody who looked like he might age into Willis’s face. “I made a facial piece — the nose, upper lip, and lower lip — and a plastic piece to pull back his ears. But actually, not much could be done to make Joseph look like Bruce Willis. They’re just way too different.”

Finally, in 2011, after a decade of working up the courage, Tsuji left the film industry and became a sculptor full-time. Following in the tradition of his Dick Smith portrait, he makes gigantic busts of people he admires: Frida Kahlo, Salvador Dali, Abraham Lincoln. Each of them features a similar enigmatic expression. “When I was a kid and I had a problem with my family, I had a habit of looking at people and without words trying to understand what was going on inside of them,” he said. This fascination is present in his art. “The important thing is sculpting one moment in a way that mixes many different emotions. It doesn’t move, but I always try to put in movement by sculpting almost the beginning of an expression. It’s like a tipping point of something happening.”

“In the movie industry, we wait for the next job and once a job comes in we live for a while and then take another job,” he said. “But in fine art, I am the one who has to make a move to make something happen. That’s a great realization about the whole concept of life: Okay, it’s not easy, but it’s very important to have control over what happens next. I think the quality of my life is better — maybe not financially, but mentally.”

When it comes to Looper; Tsuji is his own harshest critic; Darkest Hour director Joe Wright was blown away. “I thought that was astonishing,” he said. “Because it wasn’t showy, and it hit that sweet spot of being totally believable and yet fulfilling the quite dramatic narrative requirement. It made me think he was definitely the man for the job.”

In prepping for Darkest Hour, using heavy prosthetics on Oldman was always the plan. As the actor put it: “I didn’t want to gain 60 pounds and mess with my heart and my liver.” Makeup was always going to be “the roadblock,” he said. “If you see it done badly, then you are always aware of it. I didn’t want to look ridiculous — a man in a rubber face.” Oldman knew Tsuji through their mutual friend Juliet Landau, and had always loved his work. “He’s a real artist. It needed that, because we’re asking someone to believe that I’m Winston Churchill.” Coincidentally, Tsuji’s workshop was close to Oldman’s house. “It was great, because it wasn’t, you know, ‘He’s great, but he lives in Finland.’ He was actually 25 minutes away.”

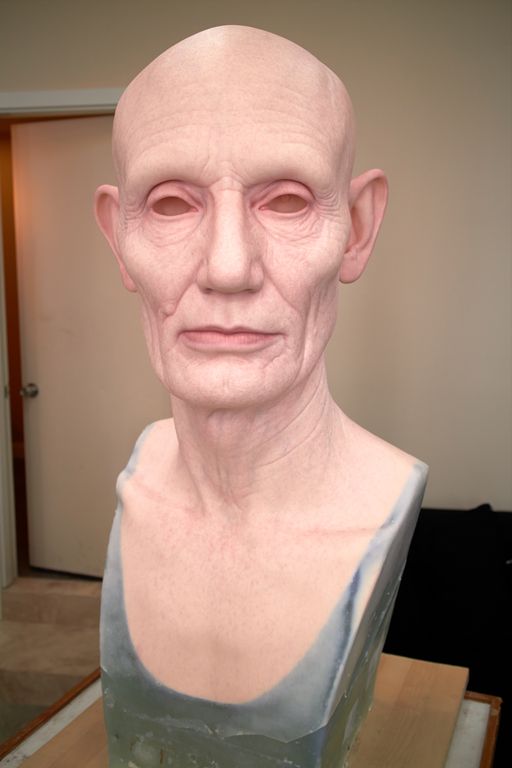

After Oldman convinced Tsuji to come out of retirement, the three men began six months of makeup testing. “There were a number of iterations,” Wright said. “The first iteration, I asked for three versions: most, least, and somewhere in the middle. The first version we saw was the ‘most,’ and although it looked even more like Churchill, one could certainly feel the prosthetics. More importantly, one had lost all accessibility to Gary and his performance. And that was really the challenge for me. I trusted Kazu, that he was going to make the thing look utterly believable, but I had to make that leap of faith.”

Tsuji soon learned not to do too much. “Because Gary is at an age where the skin is so flexible, when we put something on, it doesn’t move as good as his,” he said. “Every time we have fake skin on the actor’s skin, the movement will be diffused. Gary’s such a great actor. He has a lot of subtle expressions — a little twitching of the eyes or a slight expression on the forehead. I didn’t want to kill those.”

And changes somewhere in the face could lead to problems elsewhere. Take the difference in the two men’s head shapes. If Tsuji made Oldman’s face wider and rounder to mimic Churchill’s infantile proportions, that would also make his eyes look even smaller and closer together. “It’s like walking the wrong way,” he said.

After plenty of mixing and matching — “the chin and the nose with the brow, without the brow, the eyebags with the chin but not the nose,” as Wright put it — they found the sweet spot. The engines of Oldman’s acting, his eyes, forehead, and mouth, would be prosthetic-free. (To attain the illusion of the actor’s eyes being bigger, Tsuji decided to pluck his eyebrows.) The cheeks, jowls, neck, and chin would be makeup, and a small bit on the nose would give Oldman a hint of Churchill’s famous pug nose. He also shaved his head, so that a wig could get the hairline just right.

To mimic Churchill’s elderly wisps, that wig was made out of the most delicate materials possible. “Baby hair is the most expensive hair, because it’s very fine, very thin, and has great texture. It’s of great quality.” Tsuji said. Baby hair? “No one is killed. A baby grows hair and sometimes they decide to cut it. The problem with baby hair is that that it’s so short, usually like five or six inches. but it’s great hair to use on the hairlines because the hairline has finer hair.” Production ended up using a mix of adult and baby hair; because the wig was so fragile, Tsuji needed to make a new one every ten days.

Besides the prosthetics, the makeup job also called for, well, makeup. Tsuji did an “incredible painting job,” Wright said, “every day creating the pink, blotchy, boozy complexion.” That’s not a shade seen often in Los Angeles, so Tsuji filled his studio with visual references. “His wall by his makeup chair became plastered with these grotesque macro closeups of English pink complexion and blood vessels,” the director said, laughing.

To hear everyone tell it, the experience was absent the tension had driven Tsuji into retirement. “Kazu is one of the sweetest people I’ve ever met in my life,” Oldman said. “He is very direct, and I think that’s partly because of the language. If you say, ‘Will this work?’ he doesn’t say, ‘Well …’ He says, ‘No. That’s no good.’ And you go, ‘Okay.’ He’s very no-nonsense, but I find Kazu utterly adorable and charming.”

As part of his deal for signing on, Tsuji didn’t have to do any of the on-set application that had given him so much anxiety; that was handled by David Malinowski and Lucy Sibbick, who worked off his detailed instructions. “I realized that there’s a way to work on a film job without stressing myself out,” he said. “As long as I do the test makeup and design and everything works right, I don’t have to be on set.” Instead, Tsuji worked the entire time from his studio in Los Angeles, where he’s most comfortable.

“His studio is in this warehouse downtown, but not trendy downtown, with kind of high security fences around it, and this whole security entrance to get in,” Wright said. “And in it is Kazuhiro … he sleeps there, eats there, works there. It’s just this extraordinary world that he’s created for himself to be able to do his work. He’s a very, very single-minded individual.”

Additional reporting by Kyle Buchanan.

* This piece has been updated to clarify Tsuji’s work on Benjamin Button.

* A version of this article appears in the November 27, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.