Wormwood is about Eric Olson, an eloquent, edgy man in his early 70s. He is haunted by the death of his father, biochemist Frank Olson, who jumped out of a 13th-floor window of the Statler Hotel during a trip to New York on November 28, 1953. Or maybe he was pushed. Or forced to jump. By the CIA. Which made him take LSD.

Like every Errol Morris documentary, the Netflix series Wormwood, which opens simultaneously in limited release as a 241-minute, two-part theatrical feature, is a story about storytelling. It’s obsessed with different ways of seeing, with hiding and seeking the truth, and with the place where subjectivity shades into speculation or falsehood. It’s a documentary, but also a historical drama with actors and imagined dialogue. After a while. the pieces fuse in a manner that makes categorical distinctions seem quite beside the point.

This is an amazing story on its face. But the longer that Eric Olson, the film’s main witness, talks about his father’s murder and his lifelong obsession with it, the more layers it discloses, and the more tangled and contradictory and mysterious the details seem. Without giving too much away — though I don’t know how much a word like spoilers really applies here, considering that Morris never definitively determines what happened — Frank Olson and some colleagues got involved with the agency’s experiments with LSD. The Rockefeller Commission report of 1975 revealed that the CIA had in fact dosed Frank with LSD without his knowledge, via a spiked drink, and after that, his personality changed and he became obsessed with a particular aspect of U.S involvement in Korea, and …

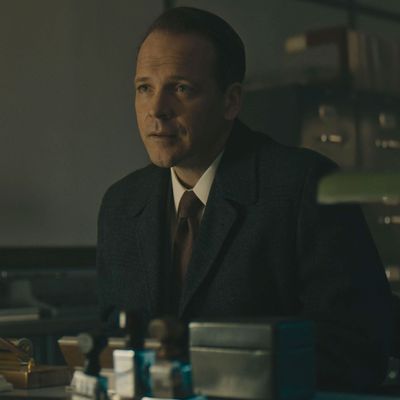

Well, maybe it’s better if you let Wormwood explain the rest, through a mix of visually fragmented present-tense interviews, newsreel footage, headlines, photos that have been treated to look like microfiche imagery, and lengthy, scripted dramatic scenes that star Peter Sarsgaard (note-perfect as Frank Olson), Tim Blake Nelson, Bob Balaban, Molly Parker, and other actors who look like they’d be at home in a circa-1953 issue of Life magazine.

What’s most compelling here isn’t the tale itself, much of which is 40 to 60 years old, is riddled with ellipses, and feels like one of those hepcat paranoid thrillers James Ellroy cooked up when he wanted to be Norman Mailer; it’s the way Eric Olson and other witnesses (including legendary-slash-notorious investigative journalist Seymour Hersh) try to put the pieces together. Morris, who can also be seen onscreen asking questions and listening, looms over the whole thing. As in most of the work he’s made in the aftermath of 1988’s The Thin Blue Line, in which he finally traded in a once-minimalist style for a kind of grandiose maximalism, this one is a tour de force of image and sound and music (by Paul Leonard Morgan, working in a churning, hypnotic-dire mode that seems to make time stand still even when there’s a lot going on).

Wormwood is framed in wide and narrow CinemaScope ratio. The director treats the skinny rectangle as a canvas upon which he can visually work through metaphors explored during the interviews. The cinematography (by Ellen Kuras, who shot the interview scenes with ten cameras, and Igor Martinovic, who shot all the 1950s scenes) often gets chopped up or arranged in glittering mosaic patterns. These seem random and pointlessly ostentatious until you spend a bit of time with Olson the younger and realize that, as he so often does, Morris is painting a portrait of the inside of this man’s mind, trying to find a filmmaking corollary for his subject’s preoccupations, the connections he makes, and the darker places in his heart.

There’s a fair amount of discussion of reflections, mirroring, concealing, and revealing, the fracturing of established narratives or “clear” pictures, and the like, as well as moments where the picture becomes blurry, goes dim or black, and blazes back to clarity. Such flourishes will either challenge or alienate the viewer, depending on their tolerance for that sort of thing. But while they risk overwhelming us, they never feel completely unjustified. They jump off from things that people said, or from ideas or images contained in news stories or government documents pertaining to the mystery. They also connect with all the discussion of LSD, which not only induces hallucinations, but also disrupts ingrained thought patterns and encourages free-association.

The clips from Laurence Olivier’s Oscar-winning 1948 film version of Hamlet, for instance, wouldn’t be in there if Olson didn’t liken himself to the title character, and his predicament to the story laid out in the play itself. The title of the series is taken from Hamlet’s aside in the play: “Wormwood! Wormwood!” Wormwood is also a star falling to Earth in the Biblical Revelations (translated from a Hebrew word for “curse,” a woody shrub that can be turned into an aromatic dark green oil or used as an ingredient in absinthe, and an alleged antidote to hemlock, which some have speculated is actually the poison used in Hamlet (though Shakespeare used the word hebenon to describe the poison poured into Hamlet’s father’s ear by his brother Claudius). Of course, all this talk of poison syncs up with the speculation on how Olson the elder ended up with LSD in his system in the first place, possibly against his will. That Morris used the ’40s film version of Hamlet, which a man of Olson’s generation probably saw as a child, rather than of any of the other adaptations that have been filmed since is just one indicator of the level of care that’s gone into this production.

The filmmaking gathers all the bits and pieces of the story together and arranges them in ways that are clever, surprising, and so aggressively (and deliberately) self-conscious that there are times when the whole thing gets close to turning into an intellectualized formal exercise. There are times when you might question whether six hours was necessary to tell this particular story — I often wonder that about Netflix productions — but there’s never a moment where Olson or Morris fail to fascinate. The hardened grief at the center of this imaginative labyrinth anchors all of Morris’s filmmaking experiments and keeps the totality of the series from disappearing into its own navel. Olson’s sorrow is evident no matter how much delight he takes in philosophizing with Morris, connecting dots, and playing amateur sleuth with his own memories. As long as he lives, he’ll always be that boy whose father died falling from a window. Wormwood never forgets that.