ItÔÇÖs hard to get excited in January, that darkest, coldest month when the hard work of resolutions begins and the best movies, shows, and midterm elections seem so far away. But you donÔÇÖt have to wait long at all for the best books (the first one arrives in a week). Here are the ten weÔÇÖre most excited about ÔÇö a partial list, because who knows what autumn will bring? ÔÇö but a very good one.

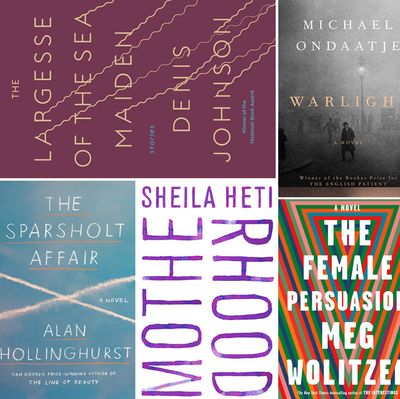

The Largesse of the Sea Maiden, by Denis Johnson (Random House, Jan. 16)

The late Denis Johnson didnÔÇÖt write enough short stories, even after getting more attention for his casually stunning 1992 collection JesusÔÇÖ Son than for his many novels. He died last May, at 67, before the publication of this second batch. The two collections complement each other ÔÇö the first concerned with wasted youth and the (richer, wearier) second with the realization that the end is closer than the beginning. But Johnson himself didnÔÇÖt burn out or fade away; he died in his prime.

Feel Free, by Zadie Smith (Penguin Press, Feb. 6)

Lots of novelists can write a pretty good essay, but there are Smith fans who believe her nonfiction surpasses the fictional works she has created. In this broad collection of pieces, SmithÔÇÖs intelligence roams up and down the culture scale ÔÇö Key & Peele, Karl Ove Knausgaard, Jay-Z, J.G. Ballard ÔÇö freely and associatively but always ready to crack the whip of judgment that binds everything together. You donÔÇÖt have to agree with every argument to admire the wit and soul of nearly every sentence.

The Line Becomes a River: Dispatches From the Border, by Francisco Cant├║ (Riverhead, Feb. 6)

WeÔÇÖre surely bound for a year of immigration stories, but this one will stand out for its dramatic emotional arc and its many perspectives. Cant├║, a writer whose Mexican mother had been a Texas Ranger, decided to work with the border patrol in order to really understand the issue. Five years later he left, disillusioned by the violence and callousness he witnessed. But when an undocumented friend gets into trouble after a cross-border visit to his dying mother, the narrative becomes both sharply political and deeply personal.

The Sparsholt Affair, by Alan Hollinghurst (Knopf, March 13)

The British reviews have it that HollinghurstÔÇÖs new novel has surpassed even his Booker Prize-winning 2004 novel, The Line of Beauty. WeÔÇÖve been promised an intricately plotted, tone-shifting look at several interconnected generations of gay men: first the codes and liaisons of World War II, then the loucheness of the 1970s, followed by the gradual tug of war between mainstream, married maturity and the zipless app-enabled culture of now. ThereÔÇÖs even a political scandal thrown in for good measure.

The Female Persuasion, by Meg Wolitzer (Riverhead, April 3)

Wolitzer has always found a way to write engrossing, smart, and breezy books that also cut to the heart of the conundrum of living as a woman in the world. Her first novel since the best seller The Interestings will focus on the generational tensions among modern feminists. A college woman named Greer finds empowerment from a much older feminist on campus, only to grow dismayed and confused as the latterÔÇÖs outlook clashes with todayÔÇÖs hashtag intersectionality.

Motherhood, by Sheila Heti (Henry Holt, May 1)

Autofiction written by women can touch on different concerns than the male variety (Knausgaard, Ben Lerner) ÔÇö though thereÔÇÖs plenty of sex and politics in both. Like HetiÔÇÖs first novel, How Should a Person Be?, this one straddles essay and memoir and philosophy. But where Person was about coming of age, Motherhood signals a turn to the next phase of life. The twist is that the central question is not ÔÇ£How should a person motherÔÇØ but ÔÇ£should one mother at all?ÔÇØ

The Mars Room, by Rachel Kushner (Scribner, May 1)

KushnerÔÇÖs last novel, The Flamethrowers, crisply brought to life the radical art and politics of the 1970s through the eyes of a passive, albeit very observant female witness. The authorÔÇÖs roving political awareness will now alight on the American prison system ÔÇö specifically the life of a California woman whose life has gone wildly astray, resulting in two consecutive life sentences. From another writer it might sound lurid or, worse, like homework. But KushnerÔÇÖs writing and thinking are always invigorating, urgent, and painterly precise.

Warlight, by Michael Ondaatje (Knopf, May 8)

In the 25 years since Ondaatje published The English Patient, which won a Booker and spawned an Oscar-winning film, heÔÇÖs written three equally good novels but lost some fair-weather readers. This one returns to World War II, the terrain of his greatest hit, albeit on the London home front. A brother and sister are taken in by a strange group of grown-ups after their parents leave for an unexplained trip to Singapore ÔÇö one of many mysteries that will take a dozen years to unravel.

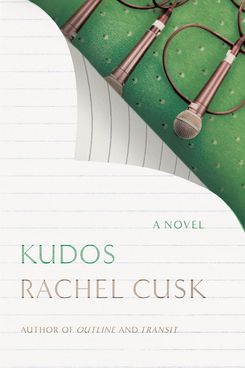

Kudos, by Rachel Cusk (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, June 5)

Literary writers have caught on to the genre trick of building loyalty and buzz (and worlds) by doing a series. CuskÔÇÖs trilogy began with OutlineÔÇÖs unnamed writer teaching a summer seminar in Greece. Transit gave her a name (Faye) along with two kids and a half-built London house. Kudos will send her across Europe to survey a continent whose center isnÔÇÖt holding. CuskÔÇÖs Faye is a deeply compelling voice but also a medium for people around her, ever telling their stories. ItÔÇÖs an ingenious way to build a world ÔÇö toward what end, weÔÇÖll soon find out.

Lake Success, by Gary Shteyngart (Random House, Sept. 4)

ItÔÇÖs been seven years since weÔÇÖve had a novel from the helplessly funny author ÔÇö during which he did grace us with Little Failure, a comic memoir with a few deftly placed sucker punches. His last novel, the long-ago Super Sad True Love Story, will be hard to top ÔÇö funny and tragic and a shockingly prescient piece of dystopia to boot. But Shteyngart thrives when treading new ground, and this story ÔÇö of a narcissistic hedge-funder who flees his family to travel cross-country in search of his lost youth ÔÇö is certainly that.