In awkward stutter step, corporate comics have attempted to get woke in recent years. The Big Two publishers, Disney-owned Marvel and Time Warner–owned DC, have made changes that put a few nonwhite and female characters into the spotlight: a woman assumed the mantle of Thor, Iron Man was replaced by an African-American girl, and a Pakistani-American girl became Ms. Marvel, among other switch-ups. There have been a handful of high-profile hires of women and people of color into creative positions, including Ta-Nehisi Coates, Roxane Gay, Rainbow Rowell, and others.

In an entertainment landscape where inclusivity is increasingly de rigueur, such moves make sense, but they often ring a little hollow. There was a black Captain America for a little while, but he eventually relinquished his star-spangled shield. There’s an Afro-Latino Spider-Man, but he’s regularly upstaged by the still-around white one. And their adventures are almost always written by white men, as they still form an overwhelming majority of the comics industry’s key employees.

In light of all that, David Steward II and Carl Reed aren’t impressed with the mainstream’s slow crawl into the 21st century. Both African-American men, they’re co-founders of Lion Forge Comics, an upstart publisher that recently launched its own superhero universe starring and created almost entirely by people who aren’t white males. Sitting in a pan-Latin steakhouse in Hell’s Kitchen, they calmly express their disdain for the big boys on the block.

“When they do diversity, it’s all almost …” Steward says, trailing off.

“Reactionary,” Reed finishes from across the table.

Steward nods and adds, “It’s almost kind of an advertising gimmick of sorts. They take Thor and make female Thor, but female Thor is going to go away, you know? If you’re really going to invest in that at that level, then it needs to be a new character with its own origin that you’re going to push and pull and really get behind.”

Reed is on the same wavelength. “We’re just coming up with characters that represent the world as we see it,” he says.

For them, inclusivity isn’t merely a high ideal. “There’s an opportunity there, too,” Steward says. “You can carve out the right niche. There’s a way to blaze a new path.”

In other words, being progressive is arguably Lion Forge’s biggest selling point. They’re not alone. The company is part of a new vanguard of small comics publishers who are attempting to grab eyeballs and dollars by embracing progressive politics both behind and inside the pages of their products. There have historically been other indie publishers who have brought people other than white men to the fore, but never before have this many companies made it a part of their bedrock mission. It’s a bold and largely unprecedented experiment for a notoriously innovation-averse industry — and it’s an uphill climb.

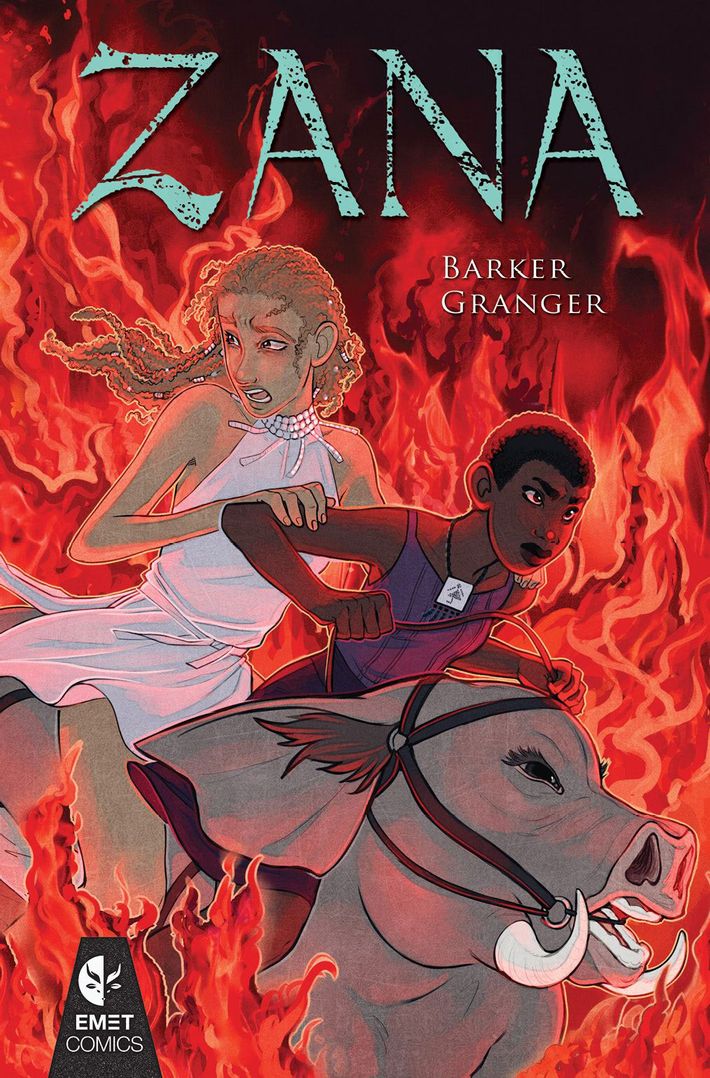

“The big challenge is just, how do you get the book in front of the right people? How does a book find its audience?” says Maytal Gilboa, founder of Emet Comics. The company, founded in 2015, has put out an array of comics that place women and girls in the spotlight, and it’s struggled to gain a foothold. Emet has drawn critical acclaim for works like Jean Barker and Joey Granger’s Zana, which depicts two girls’ adventures in an alternate universe where South African apartheid never ended; and Melissa Jane Osborne and Veronica Fish’s The Wendy Project, in which a girl confronts trauma by engaging with the Peter Pan mythos. But for the first two years of Emet’s existence, Gilboa wasn’t able to convince the industry’s near-monopolistic distributor to comics shops, Diamond, to carry her titles. It wasn’t a matter of bigotry, just lack of confidence on Diamond’s part that a tiny company like Emet could move enough product.

The key to convincing them, in Gilboa’s mind, was building a grassroots fan base online and at conventions by wearing her politics on her sleeve. “Our mission statement is very clear: We are a place that is 100 percent focused on empowering female creators, in expressing a female point of view on the world,” says Gilboa. “I think that’s why we’ve been able to build a company relatively quickly, and be relatively successful: because of how clear our brand and our messaging is.” Last year, Diamond finally took the plunge and started distributing her.

Not everyone takes Gilboa’s route of trying to break in with Diamond. C. Spike Trotman is one of the biggest success stories in the progressive small publisher movement, and when the distributor comes up, she doesn’t mince words. “Diamond can suck my taint,” she says in a dulcet lilt. The company she founded and runs, Iron Circus Comics, largely eschews the comics-shop market, preferring to focus on libraries, bookstores, and online sales. That’s unsurprising, given that Trotman has always held a special disdain for the gatekeepers of the mainstream comics world. She’s loved comics since she first discovered the funny pages in her youth, but growing up as an African-American girl, she didn’t see herself represented in the strips she perused. After getting a degree from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago at the turn of the millennium, Trotman pondered comics as a career. She quickly realized that there was virtually no one who looked like her in positions of leadership.

“I remember making a decision early on with my first exploratory forays into the comics industry that there was no seat for me at this table, and if I wanted to do this, it would have to be under my own steam,” she says. It was the dawn of the era of webcomics, and she began writing and drawing her own, an idiosyncratic slice-of-life strip with a diverse cast of characters called Templar, Arizona. Making money was a challenge — she relied on a digital “tip jar” and on flouting PayPal rules against preorders for collected editions of her books. But she relished her freedom. As she puts it, “There was no one sitting behind a desk looking at your work going, ‘But can I sell this to a 35-year-old white man?’”

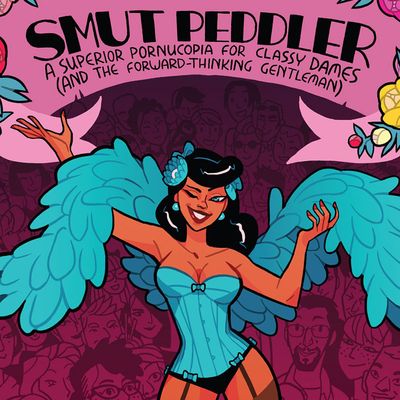

Templar, Arizona received shouts of praise, but Trotman’s greatest fame has come as a publisher. She founded Iron Circus in 2007 in order to sell her own work, but within a few years, she turned her attention toward that of other people. The company made its biggest splash in 2012, when it launched a Kickstarter for Smut Peddler, a collection of erotic comics made solely by women. She asked for $20,000 but made $83,100 after the effort went viral, thanks in no small part to Trotman’s distinctive voice on social media. Since then, Kickstarter campaigns have become Iron Circus’s backbone: Trotman has run 15 of them and raised $1,052,399 to date. She says the company is debt-free and even looking to hire its first non-Trotman employee this year.

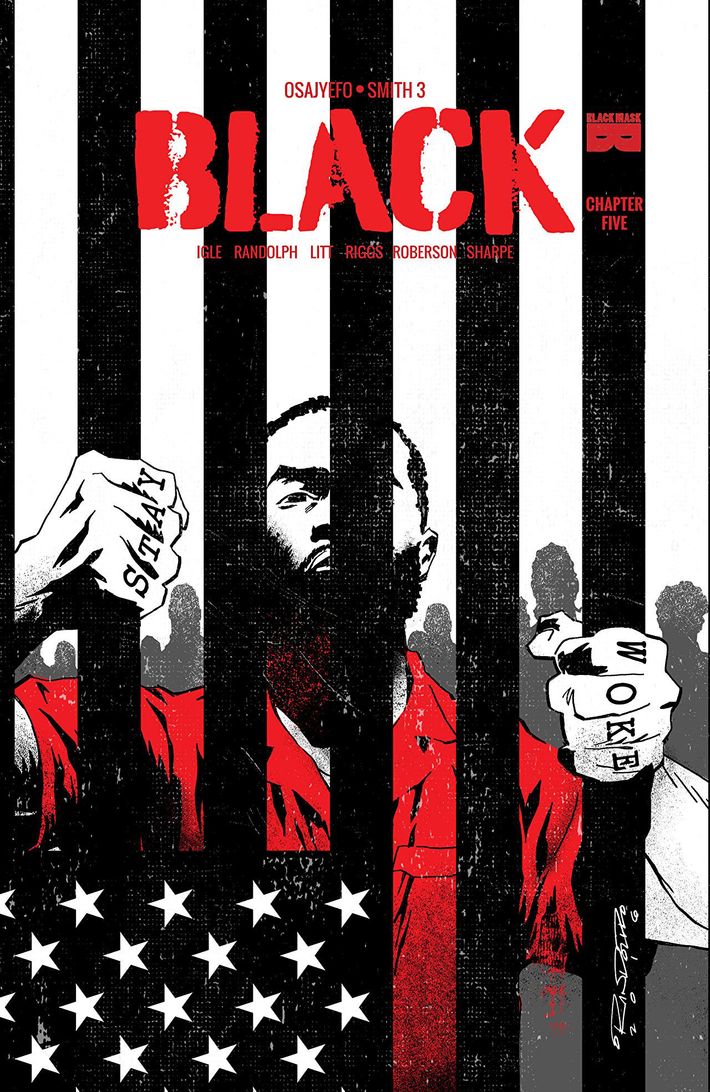

Kickstarter has been, in no small part, the paradigm-shifter that made this movement possible. For a generation of progressive geeks whose politics are primarily expressed online, being able to show your support for inclusivity by hitting a pledge button feels easy and natural. That’s the reason Kwanza Osajyefo’s BLACK exists. One of the most provocative comics on stands today, it posits a world where only black people have superpowers and was a runaway hit on the fundraising site. The appeal was in its racial politics: sight unseen, people were voting for the existence of something that would challenge the norms of superhero fiction.

Once Osajyefo and his collaborators — Tim Smith III, Khary Randolph, and Jamal Igle — had the cash, they decided to publish with another company that has made its bones by being progressive, albeit in a way that’s much more brash than Iron Circus or Emet: Black Mask Studios. Founded in 2012 by Brett Gurewitz, Steve Niles, and Matt Pizzolo, the firm has always aimed to afflict the comfortable. The company’s prologue was the publication of a Kickstarted anthology of comics about Occupy Wall Street, the proceeds of which went to buying necessities for the protesters in Zuccotti Park. The trio were able to raise the money, but Pizzolo says they couldn’t find a publisher willing to put out something so intense.

“They were nervous about doing anything political,” he says. In their discussions about what to do, the topic of Alan Moore and David Lloyd’s late-’80s anarchist masterpiece V for Vendetta came up. “What Niles said at the time, his observation from the reaction that we were getting, was that if V for Vendetta were created today, there would be no publisher for it” because it would be seen as too ideologically radical. There was a time when the Big Two took bigger risks, Pizzolo says, but now that their comics and the characters in them are lucrative cross-platform corporate products, Pizzolo thinks the powers that be are afraid to take the risk of offending.

He and his collaborators decided to self-publish and start bringing others along for the ride. “There’s something missing to support those types of works,” says Pizzolo, “and we might as well build the infrastructure in a sustainable way, to support other creators who might not have been able to find a home for something that is a little bit more politically radical, a little bit more subversive, or even just an authentic message that has a political component to it in some way.”

That mentality has been part of their DNA ever since. Black Mask’s books’ premises speak for themselves: Kim & Kim follows a pair of intergalactic queer bounty hunters, Calexit depicts a California that has seceded from the union following the election of Donald Trump, The Dregs is about gentrifiers who murder homeless people, and so on. BLACK is six issues in and launching a spinoff called BLACK [AF]: America’s Sweetheart at the end of the month, and Osajyefo believes a key reason the series became one of Black Mask’s biggest sellers is how openly progressive it is. One can see that particularly in the form of artist Randolph’s covers, which depict jarring scenes like superpowered energy coming from the arms of a lynched black man or a hoodie-wearing black teenager escaping racists on a Donkey Kong–esque journey to defeat Trump. “People aren’t gonna be able to walk past this and not at least pick it up,” he says.

However, a good cover and good corporate messaging can’t be all you have to offer. “The work, itself, needs to be good, and if it’s inclusive, all the better,” says Bay Area–based industry analyst and comics retailer Brian Hibbs. “If you’re just going in saying, ‘It’s inclusive, so people will love it,’ that’s a much, much harder sell.” It’s a sell made all the harder by the fact that the major publishers already dominate so much of the marketplace. Comics shops tend to stock nearly all of the titles put out by the Big Two and only have so much shelf space left over. “I once calculated that after retailers got through all the major publishers and halfway through the minor ones in the back of the catalogue, they’d bought 95 percent or more of the books they were going to,” says industry analyst John Jackson Miller — meaning the remaining 5 percent is a free-for-all. “On the publisher side, that means that unless you’re coming in with a name creator or a familiar license, getting retailers to notice you will be a struggle.”

All of which means you have to win over retailers with good content and a promise that the content will keep coming out. As Steward and Reed of Lion Forge point out, it’s a lesson for progressive publishers that’s as boring as it is essential. “Retailers have to understand we’re not just this company that’s saying, ‘Hey, we came up with a good idea and we’re going to push that on the marketplace,’” says Steward. According to him, when talking with retailers, “we start off with that, but then it goes through a very rigorous process of who’s going to buy it, where do we need to position it, where’s the marketing behind it. Getting them to understand does it make sense to actually put this book out to market.”

Doing so has been a learning process for Lion Forge. After the company first started in 2011, their initial touts were a licensing deal with NBCUniversal (they put out comics adaptations of old shows like Knight Rider and Punky Brewster) and a digital-first philosophy that made paper comics a lower priority than online ones. However, the licensed comics could only generate so much buzz and digital-comics sales have plateaued in recent years, so they pivoted toward inclusivity, selling themselves with the motto “Comics for Everyone.” One of the centerpieces of that effort was last year’s launch of Catalyst Prime, the aforementioned diverse line of superhero comics, where the leads run the gamut from a Mexican-American super-speedster to a hero with Down syndrome. Steward and Reed also trumpet the critical success of a non-superhero effort they put out last year: Katie Green’s graphic memoir about living with an eating disorder, Lighter Than My Shadow.

But Steward and Reed — as well as everyone else in this movement — are fully aware that they’re currently microscopic players in the comics game. One has to keep expectations low and ideals high. Everyone has their own strategy for staying motivated, and Trotman, in particular, draws strength from the idea that she’s defying the Twitter and message-board trolls who tell her that comics doesn’t want voices like hers. “I’m the person who’s making a queer witch rally-racing comic; I’m that person publishing a book about what it’s like to read banned books in South Korea under fascism,” she says. “They’re the ones posting on 4chan. I’m the one making a million dollars on Kickstarter. Who are you going to believe?”