Released almost exactly 25 years after the start of the siege of the Branch Davidian compound, Waco tries to illuminate the worst law-enforcement-driven massacre in American history from the perspectives of U.S. law enforcement and the Davidians simultaneously. I can’t speak to the totality of this six-part series, since the Paramount Network only released the first three episodes for review, but on the basis of the first half, I tentatively recommend Waco to those who only know the outline of the event. It helps to do a bit of reading for a fuller picture, though, as the storytelling elides some of the more troubling facts about David Koresh (namely allegations of statutory rape and child neglect and abuse) in order to amplify the already justifiable outrage against the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, which stormed the compound twice and is primarily responsible for the deaths of 76 Davidians and four ATF agents.

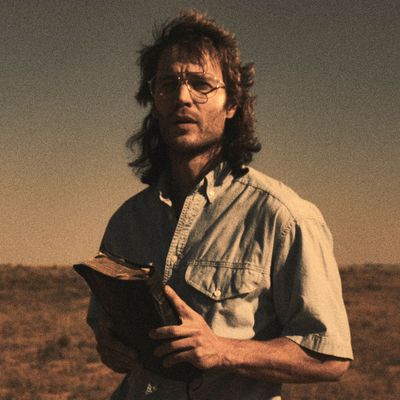

My point here is not to suggest that the series needed to paint Koresh and the Davidians more unflatteringly in the name of phony “balance,” but that a more straightforward and unflinching portrait of that aspect of the story — as well as the Davidians’ homegrown sexual and theological beliefs, which were well outside the American mainstream — might’ve better served the notion that nobody deserves to die like that, no matter who they are, how they worship, or how strange their culture might appear to outsiders. One of the most pernicious ideas in American popular culture is that it’s only a tragedy when innocent or nice people, or people who are somehow “just like us,” die at the hands of law enforcement. Waco was uniquely positioned to refute that idea, given that it’s populated almost entirely by the sorts of people who appear in sentimental New York Times articles about Trump loyalists. But it doesn’t go nearly as far as it could’ve, given what a quietly charismatic star it has in Taylor Kitsch as David Koresh, and how immediately human all of his followers seem.

All that being said, this is still a necessary and sometimes powerful series, particularly in the third hour, which depicts the initial assault on the compound that led to the two-month siege. At a time when police misconduct and the militarization of law enforcement is a constant subject in the news, Waco shows the pre-9/11 version of that mentality, as well as some early attempts within law enforcement to warn where it might lead. Created by John Erick Dowdle and Drew Dowdle, makers of the horror films No Escape, Quarantine, and Devil, the series draws on two primary sources, one from the Davidian side, the other from the FBI. These turn out to be more complementary than you might think. One is A Place Called Waco, by David Thibodeau (played here by Rory Culkin), one of the few survivors of the April 19 massacre. The other is Stalling for Time: My Life As an FBI Hostage Negotiator, by Gary Noesner (Michael Shannon), who forcefully advocated for deescalation and other nonviolent means of resolution at a time when the attitude at the FBI, the ATF, and pretty much every state or local police organization was, “Scream and curse at people continuously to disarm and surrender immediately, and if they don’t, shoot them or burn them.” That’s still the mentality in the U.S., by and large, though at least more people are questioning it, including the people who made Waco.

The story starts a year earlier with a different siege, at a compound in Ruby Ridge in Idaho, where right-wing isolationist and presidential candidate Bo Gritz (Vic Crowder) is brought in to negotiate a surrender of end-times survivalists because they didn’t trust the ATF or the FBI (why would they anyway, even before an FBI sniper shot the place up for no good reason?). Taking more dramatic license that was probably necessary, the mini-series places Noesner at that scene even though he wasn’t there, according to his own memoir — presumably to better illustrate the idea that this is what happens when you don’t listen to guys like Noesner who advise a more cautious approach. “The more force you bring to a situation, the more likely you are to meet resistance,” Noesner cautions a colleague, who looks at him as if he’s a hippie with flowers in his hair.

From there, Waco parallels Noesner’s attempt to force accountability for Ruby Ridge with life inside the compound. It’s a jumbled, unhygienic-looking place, basically a gigantic dorm that’s run like a 1960s commune. All the men pledge to remain celibate except the soft-spoken apocalyptic visionary Koresh, who takes available women as his sister wives and baby mamas, including Judy Schneider, played by Andrea Riseborough, the wife of former theology professor Steve Schneider (Paul Sparks). Allegedly he has sex with underage girls as well, according to one newspaper story that angers him, though the series never ventures an opinion as to whether these sorts of accusations were true. There are Bible study classes, rousing sermons, and quiet conversations between members of the sect (including Melissa Benoist as Koresh’s wife, Rachel) that define a different sort of normal than outsiders could envision. An FBI agent named Jacob Vazquez (John Leguizamo) takes up residence in the house next door to conduct surveillance while telling Koresh he’s a rancher who’s just bought the property. He becomes a voice of reason as well, once he goes inside the compound and looks around and concludes that while the Davidians aren’t conventional, and may be self-destructive or self-justifying in certain ways, they aren’t violent, and probably wouldn’t be unless provoked. The material in the compound occasionally evokes Big Love, in the way it envisions a subculture that exists within a larger society that would find its values and practices abhorrent if they ever posed an immediate threat to them.

The ATF unilaterally decides that the Davidians are a threat, accusing them of stockpiling $200,000 worth of weapons for some kind of end-of-the-world scenario, and of abusing children. The series’ point of view on this is that it’s a publicity move, a means of racking up a “win” after the disaster of Ruby Ridge. This has become the commonly accepted narrative now, and Waco communicates disgust with it through Shannon’s steel-willed nice-guy performance, an old-school star turn with glimmers of Henry Fonda in 12 Angry Men; his poker-faced reaction upon meeting a “special agent in charge of publicity for the ATF” is proof that a real actor can communicate alarm and disapproval even when he’s barely blinking. A secondary tragedy unfolds parallel to the one inside Mount Carmel, and it takes the form of Noesner and Vazquez (a typically superb supporting turn by Leguizamo) trying to convince the ATF and FBI that they’re headed toward disaster here for no other reason but bullheaded male pride and a wish to redeem themselves in the exact same manner that brought them disgrace a year earlier.

Waco fudges the timeline a bit between that and the start of the siege, but the larger points are forcefully made and hard to refute: U.S. law enforcement’s pointlessly macho, confrontational attitude toward its own citizens leads only to bloodshed, followed by refusals to take responsibility, which in turn leads to even more bloodshed. If the second, final assault is depicted as harrowingly as the first one, I might need to flip a coin to decide whether I want to subject myself to it. As a young writer at Dallas Observer living about 90 minutes away, I followed every day of news on the siege, heard Koresh’s words broadcast on the local radio station KRLD, and watched the compound burn on live TV. Friends in Waco told me they could see the fire and smell that crematorium smell. If Waco can revive outrage about the massacre, it will have performed a valuable public service, apart from its merits as a story.