In November, Rachel Bloom, the co-creator and star of the CW’s Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, had trouble breathing during the table read for the final episode of the show’s third season. By the time she arrived to the conference room in the North Hollywood soundstage where Ex-Girlfriend tapes, she’d been working since 6:30 a.m. and had filmed three scenes for the season’s penultimate episode, including a puppet-filled music video called “Buttload of Cats,” and was scheduled to shoot again that afternoon. “Those table-read days are the worst for me,” she says later. “But this was the first time in three seasons where my body shut down. I got cold. I got chills. I was shaking. My throat closed up and I was like, I think this is a panic attack.”

At any given moment during production, Bloom can be found writing, recording, acting, dancing, or giving notes on songs, scripts, storyboards, or rough episode cuts. She’s the prodigious talent at the center of Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, which may be the most ambitious show on network TV — a madcap musical comedy with two or three original numbers per episode often shot in seven days. For Bloom, making the show is like running on a treadmill backward in heels while singing a show tune. Or to use a bawdier metaphor she might build a song around: “I’ve described it in porn terms,” says Bloom, “in that all of my holes are filled.”

Crazy Ex-Girlfriend was born when Bloom’s co-creator Aline Brosh McKenna, best known for writing the screenplay for The Devil Wears Prada, reached out to her after seeing Bloom’s 2013 music video “Historically Accurate Disney Princess Song.” (Even that early work has many of the high-low trademarks of the show: catchy hooks and punchy, off-color, feminist lyrics.) “I see this whole show as a conversation between two ladies that started when we met and continues to this day,” says McKenna, sitting next to Bloom. “It was the only blind date that ever led to anything.”

From the outset, McKenna and Bloom envisioned Crazy Ex-Girlfriend as a four-season show. “There are very few shows where you’re like, ‘Oh you’ve got to really watch season seven.’ It’s like, ‘Eh,’” says Bloom. “We’re going through four different cycles: denial; love; turned on him; rebuilding. It was always in those four stages.”

In the pilot episode, originally shot for Showtime in 2014 (that network passed on the show before the CW snapped it up), Rebecca Bunch (Bloom) is a successful, unhappy New York attorney who bumps into her first love from summer camp, Josh Chan (Vincent Rodriguez III), near her office. He tells her he’s moving back to his hometown of West Covina, California, and she impulsively decides to follow him. The second season brings Rebecca and Josh together, only for Josh to leave her at the altar in the finale. The devastation upends Rebecca’s life, and she spends the first half of season three on a vengeance quest in the mode of a Fatal Attraction–style thriller, stalking Josh, smearing him on the internet, and mailing him poop cupcakes. All of this culminates in an emotional breakdown and her attempted suicide in episode five, followed by a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. “It was one of the things that we felt we owed,” says McKenna. “We had planted all of these seeds: In the pilot we say she throws out medication. We hear that she’s had a previous suicide attempt. We know that she hasn’t been happy with her psychiatric treatment. So we felt like she was going to bottom out before she got her diagnosis, and that’s where the attempt came from.”

In the back end of season three, Rebecca’s recovery is a one-step-forward, two-steps–back process. She’s having an affair with her boss, Nathaniel Plimpton III (Scott Michael Foster), behind his girlfriend Mona’s back (Lyndon Smith). In the final two episodes, Rebecca’s own crazy ex-lover Trent (Paul Welsh) come back into her life as she’s having a will-they-or-won’t-they moment with Nathaniel; donating an egg to another superior at her law firm, Darryl (Pete Gardner), so he can have a baby via surrogate, her roommate, Heather (Vella Lovell); and falling out with her best friend Paula (Donna Lynne Champlin).

The season-three finale, titled “Nathaniel Is Irrelevant,” is a reckoning: Rebecca realizes she needs to take responsibility for her actions; Nathaniel declares his love for her (through song, of course); and Heather gives birth to Darryl’s baby. It was a deceptively tricky episode to make, like “a carnival ride,” says McKenna. “It starts out kind of slow and gradual and you’re thinking like, This is not gonna be a big whoop. How hard is this? And then there are times where you’re screaming like a lunatic.”

For McKenna, in addition to all the other responsibilities of writing, producing, and directing (yes, she also directs the finale) a miniature musical that shoots in just eight days, there is also the ever-important job of taking care of Rachel Bloom. So when she realized Bloom wasn’t feeling well after the table read last fall, she sprang into action. “Even though Rachel’s an executive producer, it would hard for her to say, ‘I’m not feeling good and I need a nap.’ She wants to please everybody. So I say to the other producers, ‘We need to stop this,’” says McKenna. “We protect Rachel. She’s in every second of the show, so we can’t work her to the bone.” McKenna huddled with her assistant director Roger Udwin and line producer Sarah Caplan, and they flipped the shooting order of Bloom’s next scene with one of Trent’s so Bloom could rest for two hours. “And then she still had to work,” says McKenna.

The Writing

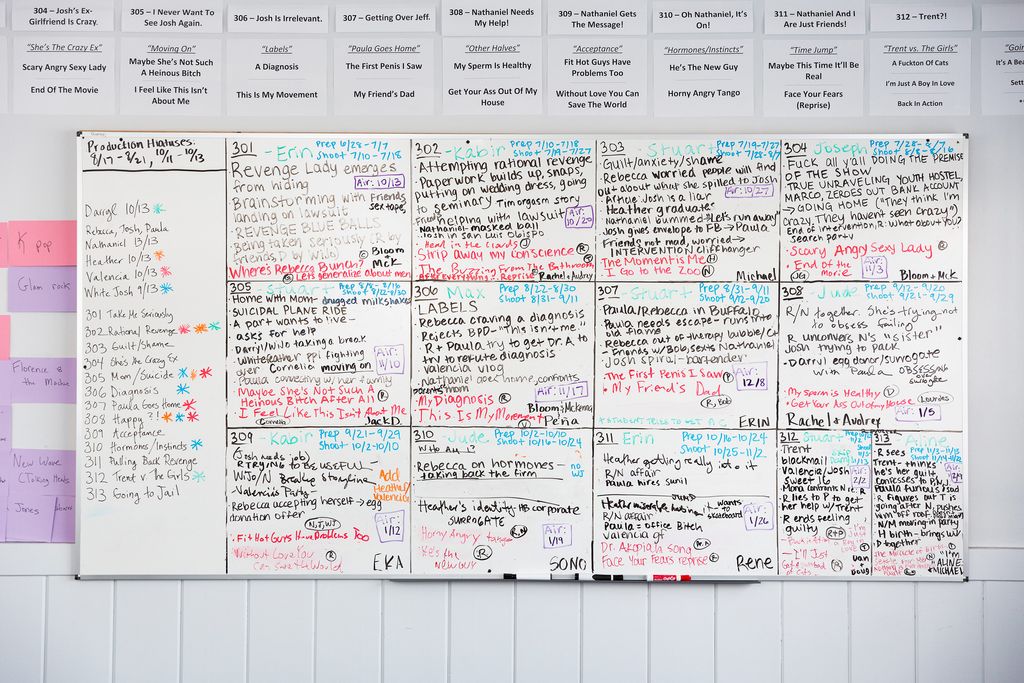

Bloom and McKenna started outlining Crazy Ex-Girlfriend’s third season in February 2017, just after they wrapped the second season. For these relaxed early brainstorms, the pair often works at McKenna’s house, and Bloom brings her dog, a terrier mutt named Wiley that McKenna calls her “niece.” They hammered out a 15-page outline of plot points and themes they wanted to hit, which they presented to the writers room in mid-May, about two months before production began. “When Aline and I are just having these sessions together, it’s a true blue sky,” says Bloom. “When Aline has a really exciting idea that’s, like, really out of the box and unexpected, she’ll be like, ‘We’re not doing this, but … ‘ And then she’ll pitch the thing, and I’ll be like, ‘That’s amazing.’”

McKenna later led the writers, a team of 13, all of whom have been with the show since season one, in breaking — i.e., plotting — the finale. They outlined the major story beats in late October, and then Michael Hitchcock, a writer and executive producer who also plays Bert on the show (many Crazy Ex-Girlfriend employees follow Bloom’s lead and do as many jobs as physically possible), spent a few days writing a first pass on the script, and passed it off to McKenna, who wrote a second. But McKenna knew it wasn’t working. “It was like I had Mr. Potato Head, but I only had the arms and legs and noses and I didn’t have the Mr. Potato Head,” she says. So she showed a draft to Bloom for notes. “Rachel was like, ‘I’m so tired that I can’t analyze it for you, I’m just going to say how I feel,’” McKenna says, flipping through an imaginary script. “She was like, ‘This is boring. I’m really confused here. What show is this? Why is this in here?’” “I think at one point I was like, ‘This made me feel sad.’” says Bloom. “This made me feel uncomfortable.” “It was great because it wasn’t constructive feedback,” McKenna says. “It was just feelings.”

Meet the Writers

Rachel Bloom

Background: Co-creator, writer, actor, producer of the show who made viral videos like “Fuck Me, Ray Bradbury” and spent many thousands of personal dollars on UCB classes.

Specialties: Musical theater, doing everything at once

Wrote the joke: Every lyric in “The Math of Love Triangles”

Favorite number: “The Math of Love Triangles” (although it could change tomorrow)

Meet the Writers

Aline Brosh McKenna

Background: Screenwriter for The Devil Wears Prada, 27 Dresses, Three to Tango, and early on the Paula to Rachel’s Rebecca. Co-creator, executive producer, writer, and director on the show.

Specialties: Romantic comedies, organization, and encouraging people to shop

Wrote the joke: When Greg tells Rebecca: “This isn’t going to be like a roll in the hay and you go home. This is going to be three days of you and me just ruining each other. And not emotionally.”

Favorite number: “Jap Battle” (It was her idea.)

Meet the Writers

Sono Patel

Background: The youngest staff writer of the group at 28, Patel grew up in Battery Park in Manhattan, before working as an assistant to screenwriter Arash Amel before working on A to Z.

Specialties: Half-hour comedies, pop music, Darryl’s midwestern sweetness

Wrote the joke: “Holy Ruth Bader Ginsburg!”

Favorite number: “What’ll it Be?”; “Buttload of Cats”

Meet the Writers

Rene Gube

Background: A former teacher of world and U.S. history, he met Bloom through UCB. He also plays Father Brah on the show.

Specialties: Mean jokes, Valencia’s narcissism, Filipino culture, SoCal, improv

Wrote the joke: Valencia telling Josh, “Ghosts are obsessed with me.”

Favorite number: “Thought Bubbles”

Meet the Writers

Rachel Specter and Audrey Wauchope

Background: A comedy-writing pair who have worked together for almost 15 years since they first met as working actors while cocktail waitressing at Lucky Strike in Hollywood. They’ve worked on Cougar Town and One Tree Hill.

Specialties: Dating while female, dirty jokes

Responsible for: The scene where Tim learns the truth about orgasms from a women’s magazine

Favorite number: “Strip Away My Conscience” and “What’ll It Be?”

Meet the Writers

Jack Dolgen

Background: One-third of the songwriting team, he’s also in the writers room and a supervising producer. He first started working with Bloom on her viral music video “Fuck Me Ray Bradbury.”

Specialties: Rock music

Wrote the joke: Heather’s catchphrase, “I’m a student.”

Favorite number: “We Tapped That Ass,” “Let’s Generalize About Men,” “We Should Definitely Not Have Sex Right Now”

Meet the Writers

Elisabeth Kiernan Averick

Background: Began as McKenna’s personal assistant, before coming on as a writers’ assistant and getting promoted to staff writer. Played the airline stewardess who realizes Rebecca committed suicide.

Specialties: Karen’s whiny voice, encyclopedic memory

Wrote the joke: Rebecca’s runner, “I’m going to hit the ladies … room, I’m not a football player.”

Favorite number: “West Covina”

Meet the Writers

Erin Ehrlich

Background: Wrote on King of the Hill, and co-showrunner of Awkward before coming to the show as an executive producer, writer, and director.

Specialties: Keeping calm, winning bets

Wrote the joke: Paula’s son saying, “Mom, I’ll get the door” because his mother just had an abortion.

Favorite number: “I’m the Villain in My Own Story”

Meet the Writers

Michael Hitchcock

Background: Writer on Mad TV, Glee, he’s best known for appearing in multiple Christopher Guest movies like Waiting for Guffman, Best in Show, and A Mighty Wind. He’s an executive producer and plays Bert on the show.

Specialties: Midwestern optimism, improv, ‘70s films

Wrote the joke: When Valencia’s teenage client says she wants a Riverdale-themed birthday party, Valencia replies, “Please. None of your friends are hot enough to be on Riverdale.”

Favorite number: “You Stupid Bitch”

Meet the Writers

Ilana Peña

Background: Writers’ assistant who got her first credit with “Josh Is Irrelevant,” which she wrote with Bloom and McKenna.

Specialties: millennial culture, tech, musical theater

Wrote the joke: When Rebecca tells Trent, “I thought you were in Iowa,” and he replies, “Io-was.”

Favorite number: “Let’s Generalize About Men”

Meet the Writers

Dan Gregor and Doug Mand

Background: Comedy-writing duo who work as consulting producers, first met in a “terrible” NYU writing class, have previously worked together on How I Met Your Mother.

Specialties: Jewish humor, random asides, improv, inability to control bowels

Wrote the joke: Greg arrives at Rebecca’s party: “Wow, this party’s a real who’s who of … who?”

Favorite number: “Remember That We Suffered”

The main trajectory of the finale, which aired in final form on February 16, tracks Rebecca’s attempts to atone for some recent misdeeds. In the previous episode, “Trent?!,” her ex-lover Trent reappears and blackmails her, threatening to reveal that she solicited a hitman on the dark web to kill Mona, Nathaniel’s girlfriend. This prompts Rebecca to ask Paula to help her find dirt on Trent. Paula initially refuses, because she’s in law school and trying to turn over a new ethical leaf, but agrees when Rebecca tells her Trent has compromising information about her too (he doesn’t).

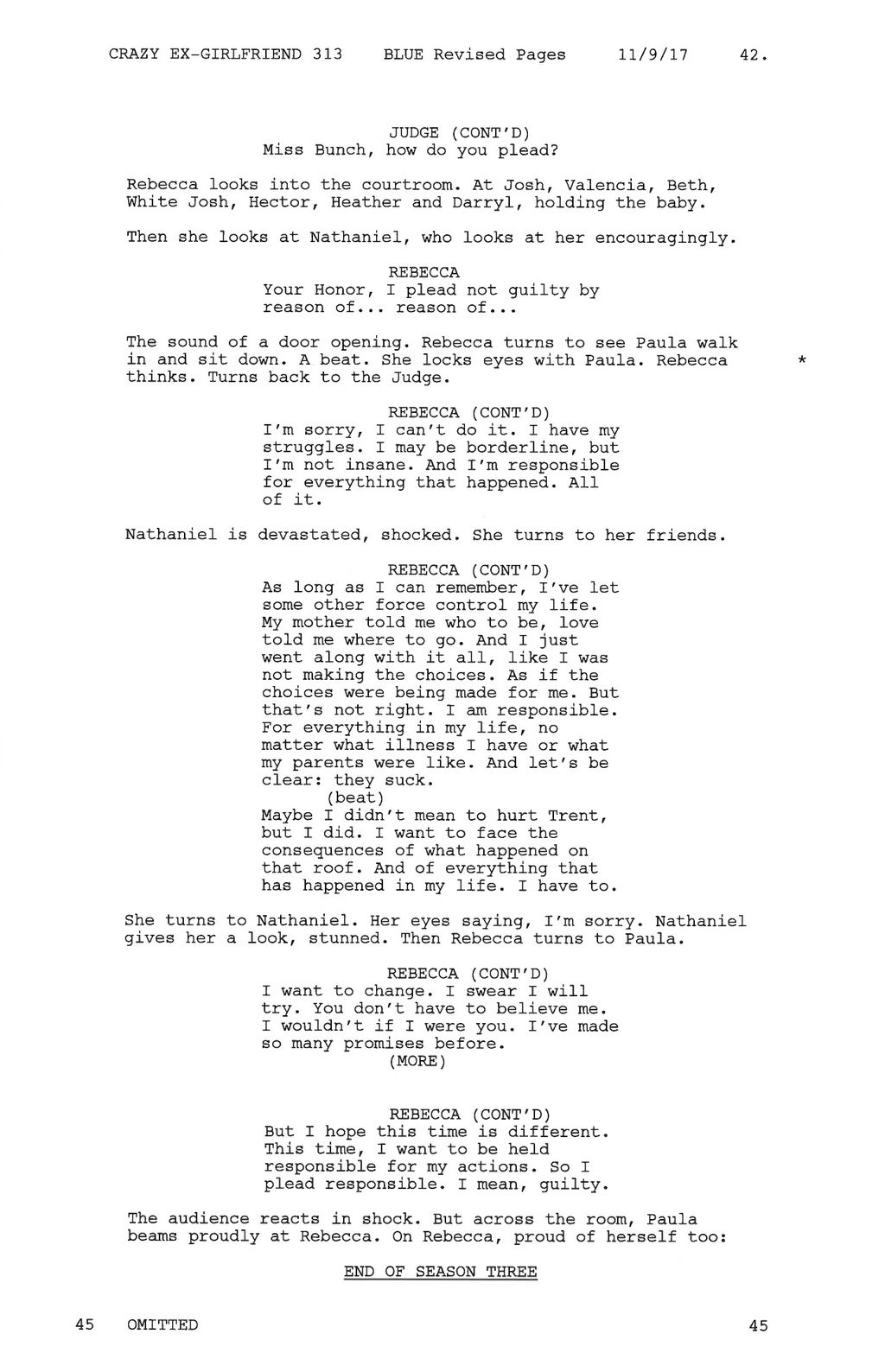

In the finale, Rebecca comes clean to Paula, telling her she lied. Meanwhile, Rebecca also discovers that Trent is planning to kill Nathaniel. And Nathaniel has reaffirmed his commitment to Mona, and the two move in together and throw a rooftop party — to which Trent shows up, disguised as a cater waiter, and makes an attempt on Nathaniel’s life. Rebecca arrives just in time to shove Trent off the rooftop and into the swimming pool, breaking every bone in his body. The police arrest Rebecca and charge her with attempted second-degree murder. Nathaniel visits her in jail, confesses that he loves her and says he’s broken up with Mona, and volunteers to represent Rebecca in court. He says her best defense is to plead insanity, and pitches her on it with the love song “Nothing Is Ever Anyone’s Fault.” Later in court, though, Rebecca makes a speech about owning up to her actions and enters a guilty plea.

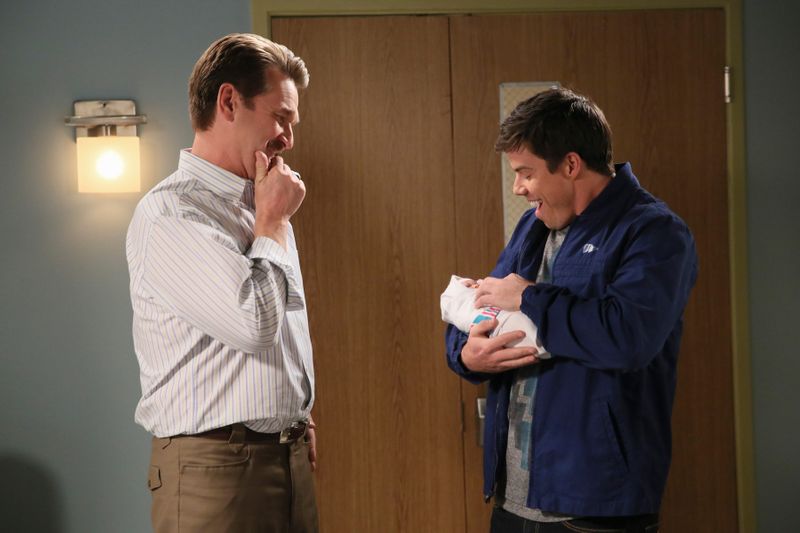

The B-plot involves Darryl’s baby, carried by Heather, Rebecca’s roommate. In the musical number “Miracle of Birth,” Paula sings to Heather about the horrors the female body undergoes during childbirth. Meanwhile, Darryl misses his ex-boyfriend, White Josh (David Hull), with whom he split because White Josh didn’t want children. Heather gives birth, and White Josh visits Darryl, and the pair reconnect.

After talking with Bloom, McKenna realized that part of the problem with the finale began with the episode prior, “Trent?!” She decided that, between both episodes, there was too much focus on Rebecca’s heartbreak over Nathaniel and on Trent’s plot for revenge. What they needed instead was conflict between Paula and Rebecca as a way to set up Rebecca’s monologue in the finale.

The next morning, McKenna, dressed up for Halloween as the show’s executive producer Sarah Caplan, gathered the writers. “I so rarely rip things up, but I told them ‘We’re going to rip some of 12, and then 13 is going to have a different spine,’” she says. “I gave them the finale draft and was like, ‘This is a hot mess.’ But from there it was a very quick rewrite.” In the original script for “Trent?!,” Paula agreed without hesitation to help Rebecca stop Trent. So it was tweaked to make Paula more of a reluctant accomplice. “A thing we wanted to add was the idea that Rebecca might actually do something to harm their relationship,” says Dan Gregor, Bloom’s husband, who co-wrote “Trent?!” with his writing partner, Doug Mand.

Pre-production had already begun on episode 12, so Gregor and Mand were careful to make edits without disrupting the production schedule too much. “All of the wheels were moving. We had the set, we had this music video figured out,” says Gregor. The changes “happened late in the process, but we were able to connect the dots and make it all work again.” For the episode 12 musical number “Back in Action,” a parody of buddy-cop movies, they tweaked the lyrics and choreography to make a running joke out of Paula’s lack of enthusiasm for Rebecca’s plan. “It definitely became a matter of fixing through the path of least resistance,” says Gregor.

The thematic arc of the finale came into focus. In the original draft of the script, Trent is stalking Rebecca for the first half of the episode. But in the revision, Rebecca (and the viewer) thinks she’s hallucinating him as a manifestation of her guilt over lying to Paula — until she actually encounters Trent in an elevator and confirms that he’s real. That she is so preoccupied by conscience helps tee up her courtroom speech, in which she apologizes to Paula.

Even though Crazy Ex-Girlfriend hasn’t yet been renewed for a fourth season, McKenna wrote this finale assuming that it would be. “It sets up the next season very nicely,” said Bloom. We’ll catch back up with Rebecca in “some sort of prison setting. We stripped away all the things she was because they were never her choices. She’s starting back at square one, because she is a stunted child.”

The Songs

“We’re trying to rhyme ‘vagina’ if you have any ideas,” says Adam Schlesinger, bassist for the band Fountains of Wayne and one of Crazy Ex-Girlfriend’s three main songwriters, along with Bloom and Jack Dolgen, who’s seated next to Schlesinger on a couch in the recording studio in the writers’ offices on set. (Dolgen is also a writer on the show, and keeps Schlesinger briefed on plot points.) Today, the day after the table read for the finale, Schlesinger and Dolgen are fleshing out “Miracle of Birth,” a song in which Paula describes the process of childbirth in excruciating detail to Heather, who’s about to go through it. “Behind-ja. Carolina,” he mutters, getting his acoustic guitar. “You can sing an octave down if you want,” Dolgen suggests. “You don’t like my falsetto?” asks Schlesinger. “I get compared to Joni Mitchell a lot.”

“Miracle of Birth” began as a discussion among the show’s writers. “The joke in the writers room is always how someone will talk about what a nightmare something is with their kids, and I’ll just say, ‘It’s a beautiful process,’” says Dolgen. “The song is about the painful, horrifying, disgusting, traumatic aspects of birth being told in a way that’s flowery, and beautiful, and trying to reassure someone: Don’t worry, it’s going to be totally fine! Your vagina tears wide open; blood and mucus come pouring out; you vomit; you shit yourself. That kind of thing.”

For research, Dolgen and Schlesinger collected anecdotes from female writers in a five-page document named “Gross Mom Stories” that covers everything from mucus plugs to walking epidurals to the placenta. (“When you need a song about childbirth, you definitely need two dudes,” jokes Schlesinger.) “I had a severely traumatic 40-minute conversation with the moms,” says Dolgen. “It’s honestly horrifying. I don’t know how they all do it.” “I’ve never seen anyone be real about birth on TV,” says Rachel Specter, one of those mom-writers. “We gave him all the really nitty-gritty details and scarred him.”

Despite its lyrical content, “Birth” is a light, folksy tune. “The music is the straight man in these songs,” says Schlesinger. “What we try to do is pick a genre and put something on top that you wouldn’t expect. That contrast is always where the comedy comes from. The music has to be the most cliché version of whatever that genre is so you understand the contrast.”

Schlesinger sets his guitar aside and pulls out a laptop, loading a few medical websites for reference and reading aloud: “Labor generally progresses more quickly for women who have already given birth vaginally.” Dolgen quips, “The good news is the next time it’ll just plop right out!”

“I like plop,” says Schlesinger, laughing, and he works it into the lyrics. “Maybe it’s funnier if it doesn’t rhyme.” He picks his guitar back up:

“Tear tear tear goes your vagina

Never will it be its cute little self again

But the good news is if you have a few more kids

The rest will really plop right out.”

Dolgen laughs, adding, “Basically plop right out!” Schlesinger likes “basically,” and the bridge is finished. About an hour later, Schlesinger plays the song for McKenna, who sits in a leather armchair and snorts as she listens. All told, it’s a smooth delivery.

The finale is supposed to include two other musical numbers: “Settle for Her” a tap-dancing number Nathaniel sings to convince himself to stay with his girlfriend Mona; and “Nothing Is Ever Anyone’s Fault,” a twisted duet between Nathaniel and Rebecca whose lyrics argue that our parents mess all of us up so badly that we can’t be held accountable for any of our actions.

Bloom and Schlesinger wrote “Settle for Her” as a callback to one of the show’s best-loved numbers, “Settle for Me” from season one, a lovesick plea from Greg, a best-friend type, to Rebecca to lower her standards. Bloom came up with a tune for the new version, and Schlesinger revised it. “Her original melody was kind of slower and a little bit more drawn out, and I gave it a little bit more bounce,” said Schlesinger. “I made it more ‘50s or ‘60s jazz rather than ‘30s or ‘40s. It feels a bit more contemporary for Nathaniel.”

The writing for “Nothing Is Ever Anyone’s Fault” came down to the wire. For a time, it was in competition with another twisted love song, “Everyone Is Crazy,” written by the trio, to be the one Rebecca and Nathaniel sing to each other. “That was just a straightforward, serious song about how Rebecca doesn’t want to plead insanity, but Nathaniel’s saying, ‘But, everyone’s crazy. That’s what you’ve shown me,’” says Bloom. “The kicker of that song was, ‘When you plead insanity, you’ll just be telling the truth. You’ve shown me I’m crazy. I’m in love with you, and that’s irrational, so I’m just as crazy as you.’ That’s a beautiful sentiment.”

But the night before the table read, Bloom talked through the scene with McKenna, and they decided to go with “Nothing Is Ever Anyone’s Fault.” “Rachel saw this love song as an opportunity for them to excuse all of the bad things that they’ve done, and we just held onto that,” says McKenna. “Nathaniel is trying to justify his love for her. She’s desperate to excuse her behavior.” All of which turns Rebecca’s final monologue into a twist: She might have been swept up by Nathaniel’s love song, but when facing the judge and her friends, she decides to plead guilty and take control of her mental illness after all.

A song can go through a few stages: Sometimes, if they’re in a rush, they’ll record a scratch track just so everyone can hear it, otherwise, they’ll record a proper demo with someone singing the song in the right key. Then comes the “playback” track the featured actor sings with final or near-final instrumentals that they’ll later lip-sync to while shooting the music video. Then, sometimes, if necessary, they’ll do another pass at the vocals after shooting the music video if they want to hone in on certain phrasing elements.

In the case of “Miracle of Birth,” after Dolgen and Schlesinger wrote the song, Schlesinger later performed the song for the writers, which they recorded on his phone and and sent to Bloom and to Steven M. Gold, the show’s music producer.

Next, Schlesinger laid down the acoustic-guitar track in the studio, and since they had extra time before production, he asked his friend, a singer-songwriter named Kelly Jones who had recently given birth herself, to record a placeholder vocal track, “for everyone to hear it in the right key, with the real melody, and for Donna Lynne to learn it,” says Schlesinger.

Champlin spent the weekend with the song and did a “prerecord” of her vocals for the playback track that she’ll lip-sync to while shooting. She experimented with different readings of spoken lines like “It’s what your body’s made for.” “Rachel would say, ‘Do we have a take of her throwing it away a bit more, or going slower?’” says Gold. “So after the recording session, there’s a lot of creative back and forth to get the best take.”

After Gold and Schlesinger cut together a track from the best available takes, and Champlin has filmed the scene, they’ll watch a rough edit of the music video to see how the audio and video sync up. For “Miracle of Birth” they replace some of the prerecorded spoken lines with ones Champlin did live during the video shoot. “Rachel loved her performance on set and wanted to get her actual recorded audio,” says Gold.

Watching the “Miracle” video inspired Gold and Schlesinger to add a few overdubs to the song, including a cascade of wind chimes in the part where the rose petals are raining on Paula. “We ended up sweetening the track,” says Gold. “Although it’s still a folksy, intimate song, we added an oboe and some pizzicato strings. That was our post-scoring.”

The timeline for “Nothing Is Ever Anyone’s Fault” was tighter. After breaking the song with McKenna, Bloom played it for her husband, who may or may not have teared up (she claims he did; he denies it). She sent a recording of herself singing the track with some rudimentary piano chords to Schlesinger, who arranged it and filled out the melody, with “All the Wasted Time” from Parade as his main stylistic reference. She sang her part for the prerecord, and Schlesinger sang Scott Michael Foster’s part. Then, Schlesinger sent a copy to Foster, who recorded his own vocals the next day.

After Bloom and Foster shot the music video for “Nothing Is Ever Anyone’s Fault” on set, Schlesinger and Gold worked with conductor David Chase, the Broadway arranger and composer with whom Schlesinger worked on the show Cry-Baby, in New York to record the orchestral arrangement — four violins, two cellos, four woodwinds, a French horn, two trumpets, a trombone, and a rhythm section with a piano, bass, drums, and mallet percussion. Orchestration recordings are in the arena of $10,000 for a three-hour session, and they have four songs to get through, including “Nothing Is Ever Anyone’s Fault,” “Settle for Her,” “This Session Is Gonna Be Different” from episode 11, and “Horny Angry Tango” from episode 10.

While recording “Nothing Is Ever Anyone’s Fault,” Chase and the musicians wear headphones so they can play along to Bloom and Foster’s vocal tracks. “The musicians are hearing the song for the first time,” says Gold. “But [Chase] knows it very well. He knows how it moves rhythmically, so he’s able to, on his baton, conduct the players to the vocal.”

Gold and Schlesinger give notes and make adjustments where necessary, and there’s a music copyist on hand to transcribe any major changes (like a key or octave change) that might require new sheet music. “One of the biggest notes on ‘Nothing Is Ever Anyone’s Fault’ was to make it bigger as it built,” Gold says.” “It builds from being intimate, with a very, very light orchestra, mostly driven by the piano track, to a lot of emotion and drama.” They ask the rhythm section to play louder in the second half.

After the music video shoot for the song, Bloom wants to rerecord the vocals “to picture.” That is, she and Foster will sing it again while watching the video. “It’s a pain in the ass, but I love rerecording to picture, because I’ve now performed the scene, I have actually felt what the emotional sweep is, and I can put that into the vocal performance,” says Bloom. “Plus, Scott and I had only learned the melody, and Adam made some significant — but great — changes to the chords. So the vocal needs to be a little more emotional from both of us.”

Bloom and Foster rerecorded their parts to picture in mid-January. Bloom directed Foster in the recording studio in L.A. while Schlesinger and Gold watched from New York via FaceTime. Bloom added “comedic, emotional, lyrical clarifications,” says Gold. For instance, when Foster sings the end of the first verse, “I understand what makes me frightened and sad. So yes, I still do bad things. But are they actually bad? No-o!,” Bloom wanted to make sure the comedy came through in that “No!” “It was like a big ‘No-o!’ and it was a very good piece of direction that made us laugh afterwards,” says Gold. “It ended up being a funnier performance than when he did it the first time.”

Meanwhile, “Settle for Her” goes through the entire process — prerecord, production, and orchestration — but is ultimately axed for story-related reasons (more on this later). “We were very, very sad it was cut,” says Gold. “The good thing is that the orchestral part recorded ended up becoming part of the score for the episode, so it wasn’t just thrown in the garbage.”

The Production

Donna Lynne Champlin sits atop a raised throne, dressed in silk chiffon, making birthing faces. The soundstage has been transformed into a vaginal wonderland with arching, membranous screens above her arranged into a proscenium for the musical number “Miracle of Birth.” It’s quiet on set save for Champlin’s grunts, squeals, and groans, ranging from the dainty to the very pregnant, which prompts stifled laughs from McKenna, the director of the episode, and the rest of the crew members who just want to ensure they get clean audio. Champlin does different cries and faces to Camera A, then Camera B, and Camera C. She adds an, “Oh! There it is!” on one pass. “How many more you got in you?” asks McKenna from the video village. “I was in labor for 15 hours,” replies Champlin, who has a 6-year-old son. “I’ve got 15 hours of that.”

It’s Saturday morning, also known as Day Four of Eight on the production schedule. Crazy Ex-Girlfriend usually shoots an episode in seven days, but since this is the finale, they budgeted extra time, even adding a Sunday of rest in the middle. (Incidentally, the cast spent that day leading a sing-along at Vulture Festival L.A. on November 19.) “Miracle of Birth” is the first of three music videos on slate.

The first three days of production were spent on scenes in the everyday world: On Wednesday (Day One), they filmed at the Whitefeather offices, the law firm where Rebecca, Nathaniel, and Darryl work; on Thursday (Day Two), at Home Base, the bar where the gang hangs out, and a couple of offsite locations nearby; and on Friday (Day Three) on a rooftop nearby in North Hollywood. They group the shots together by location for maximum efficiency, so the scenes at Whitefeather included Rebecca confessing her transgressions to friends, Nathaniel telling her she’s not invited to his rooftop party, and another in which Rebecca looks at Trent’s Snapchat. Scheduling the music videos later allows the show’s songwriters more time to polish songs and the actors more time to learn the lyrics and choreography.

“It’s pretty traditional coverage,” says McKenna of the camerawork for Crazy Ex-Girlfriend’s non-musical scenes. “I like things that are classic, clean, because that grounds the comedy. Early on, directors would try trick shots, where the shot is funny, and it didn’t work. The show is too silly to begin with, and it would just feel like a joke on a joke. So we toned it to this very simple style — with some flair.”

That flair emerges in subtle ways, for instance in a shot of a guilt-stricken Rebecca talking to Paula in the Whitefeather kitchen. McKenna wanted to do a low shot that she called her “Star Wars shot” to get a view of the honeycomb ceiling. “It’s just cool graphically, so I wanted to see what it would look like to dramatize that she is in a paranoid low feeling — like, literally the ceiling is caving in on her,” says McKenna.

In that scene and others, McKenna and director of photography Todd Dos Reis tried to frame shots of two people facing off as symmetrically as possible. For the scene in which Nathaniel visits Rebecca in an interrogation room before they sing “Nothing,” a plaque hanging on the wall was moved to be in the center between the two actors. Unfortunately, there was also an immovable uncentered radiator in the same shot. “I was like, ‘You know what? It’s okay.’ No one’s going to notice this completely nerdy thing we’re doing,” said McKenna, so they moved on.

The symmetry was a way to visually suggest that many themes and plot points — Trent’s revenge-seeking return, for example — were redolent of seasons past. “Rebecca is in an echo chamber where things are recurring,” says McKenna. “Trent mirrors her. And what’s happening here mirrors previous events, like her needing to come clean to Paula, because she lied to Paula. There’s a lot of symmetry and evenness. You’ve been here before.”

The show favors over-the-shoulder medium shots when they’re shooting dialogue and eschews close-ups or wide shots on people’s faces. “My normal lens is probably a 40mm or 65,” said Dos Reis. “A 40mm is almost like how the human eye sees. We don’t do a lot of zooming, but the normal reality of Whitefeather and Rebecca’s life is a normal lens. With the musical numbers, though, we try to push the envelope and do things that we haven’t done before.”

Work on “Miracle of Birth” began a week before the finale started shooting. Two days after the table read, the heads of various departments including McKenna, Bloom, choreographer Kathryn Burns, costume designer Melina Root, and production designer Stephen McCabe met for the “dance concept meeting.” They discussed the visual references for the number, including The Nutcracker, Beyoncé’s Instagram birth announcement, Mughal architecture, Botticelli’s “Birth of Venus,” and vaginas. Bloom had the last-minute idea to have child dancers emerge from a curtain beneath Paula’s throne.

McCabe and his team had about a week to build the throne, which involved affixing an antique chair, purchased from an antique store specializing in Indian and Middle Eastern furniture, to the top of a small pyramid, and painting it so the two parts all looked like a single unit. McCabe’s team had to be careful that the height did not exceed 45 inches; the structure had to be tall enough to allow space beneath it for child dancers but not so tall that it lifted Champlin out of the frame. “Donna Lynne has to be within the height of the children so the camera can see both of them together, ” says McCabe. “Plus we have ceiling restrictions. We don’t have a very high stage here.”

Meanwhile, Burns set to work on casting six professionally trained, SAG-card-carrying child dancers short enough to fit in the crawl space in the base of the throne. “Casting is a little difficult because the dancers have to be under three-eight, which is tricky because kids grow,” says Burns. “And they have to be technical. I would like them to be good dancers, because the song is slow, and it takes more control to move slowly.”

Still, Burns reached out to five L.A. dance agencies and found six girls who fit the bill. Once she had her crew of tiny dancers, she hired an assistant, Melinda Sullivan, to help choreograph the number. “We played in the studio just us two, but when we did moves we filled up so much space and it took more time,” says Burns. “But once you see all these tiny little bodies that are like three feet tall … We had to cut our counts in half, because they move so much faster through the world than we do.”

All six girls were highly technically proficient, and originally, Burns and Sullivan choreographed a more difficult routine. But after they saw it, McKenna and Bloom asked for a simpler dance. “Rachel and I felt like it needed to be little girls dancing sweetly like they would around a maypole in a forest and not so much the kids version of So You Think You Can Dance,” says McKenna. “So we toned it down significantly.”

There was some initial concern that the girls’ parents might balk at the content of the number, but luckily, they approved. Burns recalls: “One of the moms was like, ‘Well you came out of my vagina,’ and the little girl was like, ‘Mom!’ And she was like, ‘Well, it’s true. I gave birth. It’s in the song.’”

It’s Saturday morning, and it’s time to shoot. Champlin got into hair and makeup at 9 a.m., and followed the theme of goddess worship. The process, which took about two hours, began with setting Champlin’s hair with curlers to create “mermaid waves.” Then she headed to the makeup department, which used a palette of bronze and gold, and amped up her look by giving her individual lashes, and a shimmery body lotion to better reflect light. “We wanted her to look really stunning, and glowing, and earthy. You know, like how birth will make you so beautiful?” says Sabine Roller-Taylor, the head of makeup. “Which, of course, is not true.” Then Champlin went back to hair. “We gave her this very long, luxurious hair, so we added a whole bunch of hair extensions,” says Jeanie Duronslet, the head of the hair department. The extensions were trickier, because Champlin has a specific shade of red hair. “We hand-colored all of them,” she says. “It was really a trial and error to get the exact color. So, like, four hours of sitting there late at night trying to figure it out.”

They eventually settled on the right formula, mixing three different color glosses from Redken called Red Kicker, Papaya, and Cayenne, and then using a copper shampoo called Gem to give it more pop. “We want her to look the most beautiful she’s ever looked,” says Duronslet. “Like, if she couldn’t be more beautiful, that’s what we want. Like a fairy tale.”

The number gave costume designer Melina Root a chance to stretch, too. She often buys clothes from Macy’s or Sears, because those are the stores native to West Covina. But for “Miracle of Birth,” she created a draped gown with three layers of silk in a shade she calls a “labial pink” or “menopausal pink.” “I’ve given birth,” Root says laughing. The children’s dresses were also made of hand-dyed silk chiffon in similarly warm hues of orange and pink. “All the colors are ones we associate with birth and regrowth and regeneration,” says Root.

On the soundstage, director of photography Todd Dos Reis created backlighting to give Donna Lynne Champlin and the child dancers a “halo,” and lit the stage with clean, white beams. “The way Steve cut out the vagina walls, he had holes in them so I could have shafts of light with a little bit of smoke,” explains Dos Reis. “But when you have Donna Lynne singing, you can just let her carry the number. There’s not a lot you have to do visually, because you’re just going to be enthralled by her voice.”

As cameras roll, Champlin’s vocals — recorded a few days prior — are played through speakers, and she sings along. “You don’t have to sing out, especially not if it’s like a Mama Rose number, but you have to phonate, breathe, and sing it,” says Champlin. The key to an accurate sync, she says, is breath, cutoffs (where you end the note), and certain consonants like R’s, F’s, and T’s.

Compared to some of her other numbers, “Miracle of Birth” was a breeze for Champlin. “Normally on a musical-number day, I won’t have slept and I’ll just be anxious,” she says. “But I slept like a baby last night. This morning, I was like, ‘Ahh! I’m just going to sit in a chair and sing for some people!’”

The most adorable obstacle of the day is a 4-year old named Hazel, daughter of one of the show’s writers, Audrey Wauchope, who’s playing a flower girl who’s supposed to spread petals from one side of the stage to the other. But when it comes time to shoot, Hazel is more content to stand aside and watch the dancers. McKenna crouches on the side, beckoning her over. “There are M&M’s in it for you,” McKenna promises, and gets the shot.

After “Miracle of Birth,” McKenna was off to another part of the soundstage to block-shoot the hospital scenes with Heather (Vella Lovell) and Darryl (Pete Gardner). “It was three different scenes,” says Lovell, “the epidural, giving birth, and sleeping after birth,” two of which required a pregnant-belly prosthetic, and all three shot from multiple angles. So they would shoot all three scenes from one vantage, and then move the camera and run through them again. “Every time we changed the angle, I’d have to change out of the gown, into the belly, out of the belly, with or without sweat. I was so loopy that I just didn’t know what scene or what belly or what stage the baby was at at all!” Lovell says. “I had proper pregnancy brain by the end of that day.”

She did enjoy wearing the belly this season, though. “My character will wear midriffs, and not super-revealing clothes, but sometimes my stomach is out, and with the belly, I just didn’t have to worry about that at all.” While the male actors — Vincent Rodriguez III, Scott Michael Foster, and David Hull — had to get shredded for their Magic Mike–style number in episode nine, “Fit Hot Guys Have Problems Too,” Lovell could take it easy. “It’s crazy how the men on this show have to work out and take their clothes off, and I’m in comfy clothes eating sandwiches. It’s usually the other way around.”

We don’t actually see Heather’s labor, but Lovell did her research anyway, for the epidural scene. “I wanted it to be as accurate as possible, so I went down a home-birth YouTube hole,” says Lovell. “I never want to give birth now.” She did manage to make the contraction scene fun, though. The show encourages “fun runs” — that is, takes in which the actors, many of whom have backgrounds in improv comedy, try ad-libbing. In the shooting script, the contraction scene ended when Heather tells Darryl, “All right, let’s go, get the car.” But they shot a take in which the camera stays on Lovell as she starts calling names of ‘90s R&B singers: “Ohh, Toni Braxton. Ohh, Brandy and Monica. Aaliyah? Anybody?” “My improv usually comes at the end of scenes,” says Lovell. “Once I feel like I’ve gotten information across, I’ll add something to the end of a line. In that scene, I was just going through some ‘90s singers I thought Heather would call on in her time of need.”

If you have a birth scene in your TV show, you need a baby. And so Crazy Ex-Girlfriend needed a newborn for the scene near the end of the finale in which we see Darryl holding his new daughter. But instead of hiring a real one — infants are only allowed to work 20 minutes at a time — Crazy Ex-Girlfriend propmaster Thomas Cahill rented a $15,000 silicone baby named Dana for $1,200 for the week from makeup effects company MastersFX. Dana has an extensive résumé that includes appearances on This Is Us, The Good Doctor, iZombie, The Leftovers, and The Night Shift. At 16 inches and six pounds, she also comes with an optional penis accessory for when the script calls for a male baby.

“That doll was terrifying and awesome,” says Lovell. “It was freaky! But I guess it would have been even freakier to have to hold a real baby.” A real baby wouldn’t have looked any better, though, says Cahill. “Did you see [the silicone baby’s] skin? It’s almost translucent, they look so real.” The placenta was harder to get right. Cahill called in four different options from a few medical-supply companies. Getting the color right was tricky, because the model they chose was an unrealistic beige. “We painted it three times because it’s trial and error,” says Cahill. “Once you start putting the blue over it, everything turns purple and it doesn’t look right. So we had to start over and repaint it pink.”

The last days of production, the week before Thanksgiving, were especially difficult, because many of the cast members started to get sick — and there were still two musical numbers to shoot: “Settle for Her” and “Nothing Is Ever Anyone’s Fault.” Worse, both involved patient zero, Scott Michael Foster, who began to feel unwell on Saturday, while he was recording his vocals for the playback track for “Nothing Is Ever Anyone’s Fault.”

Two days later, Foster filmed the duet with Bloom. “I was popping DayQuil like candy and I was trying to hold it together,” he says. “But as soon as I shot that scene, which took a few hours, I slept for the rest of the day. That’s when my body finally let go, and I was sick for about ten days.”

The set for “Nothing Is Ever Anyone’s Fault,” in which Nathaniel confesses his love for Rebecca and says he’ll defend her in court, was simple: a small interrogation room. The challenge was making a small 12-by-12 room visually interesting. “As television-watchers, you’ve all seen an interrogation room,” says Dos Reis. “It’s basically a box.” So he built a 360-degree track around the two actors and surrounded them with six lights attached to a dimmer switch that would go up or down depending on the location of the camera, to always light the actors from the side or back, never the front. “They were in a black void at some point, so it’d just be lighting their faces,” he says. “We were hoping that, during the song, as the lights drop down, you wouldn’t know you were in the interrogation room. You’re just in their heads feeling this great love song.”

The last day of production was the Wednesday before Thanksgiving, and they were scheduled to begin with Foster’s other number “Settle for Her,” and end with the final courtroom scene in which Bloom delivers her monologue. But Foster was full-blown sick. He’d been to see a doctor, who told him it wasn’t the flu, but he still felt like it was. “I knew right away when I saw him that there was just no way it was gonna happen,” says McKenna. “Scott was so sick that we had to cancel his dance number. He had four lines in that [courtroom scene] and we tried to keep him seated as much as possible. It was really warm on set. Two people had migraines. It actually turned out to be great because it shortened the day and everyone was so tired. “

McKenna adjusted the cast’s call times so they could shoot the courtroom scene early and wrap for the day. “Everyone was all hands on deck as early as possible, and what I loved about it is that everyone was ready to do whatever they could for poor Scott, who could barely talk that day,” says Gabrielle Ruiz, who plays the social-media obsessed party planner and ex-girlfriend of Josh Chan, Valencia. “His body was like, ‘Enough!’”

As for Rebecca’s monologue, it was a simple production. The team built a basic courtroom set, and the costume designer outfitted Bloom in a deliberately ill-fitting orange jumpsuit. The focus would be Rebecca’s speech to the judge, and really, Paula. While the monologue is a breakthrough for Rebecca, it wasn’t an acting challenge for Bloom, because she was finally saying things that she herself might say. “It almost felt like Rachel speaking about Rebecca,” says Bloom. “It’s still Rebecca, but it’s the biggest moment of clarity that she’s had in the show. It wasn’t really a stretch to act. It was just apparent. It was just really, really apparent.”

She nailed it on the third take. “I walked over to her and said, ‘That was just really fucking good acting,’” says McKenna.

Bloom knew it, too: “Yeah, that was good.”

Editing

The soundstage is mostly empty by early January, long after production has wrapped and most of the cast and crew have gone home, except for Rachel Bloom, Aline Brosh McKenna, and the editors who handle post-production. “I think there’s meant to be a therapeutic aspect to people coming and working in post. I mean, they’re literally on a sofa,” Kabir Akhtar, one of the editors, says as he gestures to the sofa facing a wide-screen TV in his editing suite where McKenna and Bloom are sitting, Bloom in a T-shirt that reads “I’m on my period.” (She clarifies for the room: “I’m not on my period.”)

Bloom is giving her notes on the episode before they send a cut to the network, and since this is the editing process, all adjustments are extremely specific. “Her first line,” Bloom reads aloud from her notepad. By which she means the audio is slightly out of sync near the beginning of “Miracle of Birth.” Akhtar fixes it. “Yeah, that’s pretty good,” says Bloom, and they move on.

They check the other musical numbers for similar issues. “In the industry, we like to say, ‘We put it in her mouth’ if something is off lip-sync wise. That means that we move, by milliseconds, the syllables around so that it syncs better and looks more authentic,” says Steven M. Gold, who takes another look at the music videos with Schlesinger later before the final music mix. “Those are just minor little tweaks that a lot of people don’t even notice. We just try to keep it really tight with the movements.”

Bloom, McKenna, and Akhtar spend only about five minutes or so on each note before coming to a quick consensus. Bloom’s other suggestions included cutting Darryl’s reaction after Paula says, “It’s your baby!” in “Miracle of Birth” (“It undercuts the humor”). Bloom also wants to bring back McKenna’s Star Wars shot one more time during the Rebecca-Paula scene in the Whitefeather kitchen.

Akhtar is fast, and has been with the show since season one (he’s also directed many episodes), and the trio falls into an easy shorthand as they zip through edits, with a few digressions along the way: they talk about how they’d love to do something with Top Chef, how Padma Lakshmi used to take improv classes at UCB, whether “felicitate” is a word (it is), and Bloom’s plan to take the cast to Knott’s Berry Farms on Golden Globes Sunday.

Akhtar made his rough edit of the episode the first week of December. At about 52 minutes long, it included all the scenes they’d shot. Then, per DGA rules, it goes to the director, in this case McKenna, and she and Akhtar spent the next few days going through each scene. Since Crazy Ex-Girlfriend is a network show, they had to hit a very specific runtime: 42 minutes and 15 seconds. “But they let us be a bit shorter sometimes so they can sell more commercials,” says Akhtar. He likes the constraints. “It forces you to be efficient and concise in the storytelling. Sometimes it’s a drag, because you get down to within 20 seconds. Like, we’re gonna have to take this joke that’s working and we all love out.”

There were some major cuts to the finale, most of which were made to avoid spoiling twists later in the episode. Many of these had to do with White Josh’s surprise visit to Darryl at the hospital after his baby is born. One of the deleted scenes involved White Josh lamenting to his friend Hector at Home Base that he missed group hangs; another was a waiting-room scene in which a nurse ushered White Josh into the recovery room. The goal of the cuts was to make the scene where White Josh finally does show up that much more impactful. “You can imagine: you hear a knock at the door, and Josh walks in, and now we’re all feeling what Pete is playing on his face there. He’s like ‘Oh my god, what are you doing here?’ And we’re all like, ‘Oh my god, there you are.’ Like, as fans you’ve been wondering what happened,” says Akhtar.

The biggest cut, though, was the song “Settle for Her,” the tap-dancing number they rescheduled because Foster was sick. “We all watched it, and we all turned to each other and were like, ‘This doesn’t need to be here at all,’” says Akhtar. “It got in the way of the story. One of the cardinal sins is for the audience to get ahead and to know what’s coming.” They were two minutes over their allotted episode length and watching the scene, there was one particular line that stuck out:

“Despite it all, if Rebecca called, I’d be there on bended knee.

Cause deep down I still hope that maybe she’d settle for…”

“It was killing the surprise at the end,” says McKenna. The song wasn’t lost completely, though. They added a bit of the orchestral music from the November session to the rooftop scene where Nathaniel looks at Mona. “We still use that beautiful orchestral piece, and so you still have that sense,” said McKenna. (McKenna declined to share the full deleted number with Vulture “because I’m still not sure we won’t use it again somewhere else.”)

McKenna plans to watch the finale live at her house with Bloom, the cast, and some of the crew members who worked on the episode. “It’s just a fun cumulative experience. I’m sure I will see it differently than I would have seen it during the scrum of making it,” says McKenna a few days before the airdate. “It feels like a big responsibility because it’s a summation of the season, where we had to calibrate so many tones and narrative threads.”

This finale is a tricky maneuver: It needs to give closure to the third act of the show while setting up (they hope) the fourth and final season. While McKenna still hasn’t heard from the CW about a renewal, she says she wouldn’t change anything about the episode. “If the network had told me during the season, ‘This is your last,’ I’d have sort of written it differently, but I just always write as if we’re getting another season. I do think out of the ones we’ve done, this is the most cumulative and that’s because it’s so far into the story. So I guess if it was the end, it wouldn’t be the worst thing. But I do think you can tell from watching this episode that we have a fourth leg of Rebecca’s journey yet to go.”

“I hope it feels like a gymnast going over the vault,” McKenna adds, “and landing on both feet.”