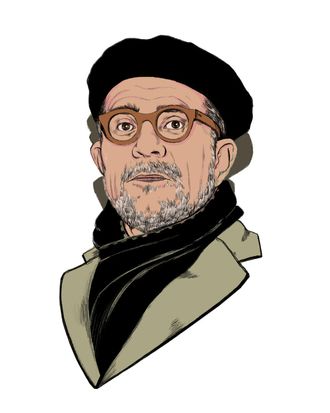

On a sunny, mid-February morning in Santa Monica, California — a far cry from the dingy, wintry, late-1920s setting of his new crime novel, Chicago — David Mamet sat down with Vulture to discuss his latest project, his love of James Cain, and his desire to eat dinner with Pancho Barnes.

My first question is about James M. Cain. You mention the real-life Ruth Snyder–Judd Gray case in the novel, which was the inspiration for two of Cain’s novels, Double Indemnity and The Postman Always Rings Twice.

David Mamet: Oh, I didn’t know that!

Yet adapting Postman is how you got your start in Hollywood.

Curiously, it was through my then-brother-in-law, a wonderful writer named Tim Crouse. He asked me if I’d read James M. Cain. I said I hadn’t since I was a kid. So I went on vacation and read every novel of Cain’s I could get my hands on. After I came back, my then-wife was going to an audition with Bob Rafelson for the movie. I told her I wanted to get a job writing the script. She said, “I’m sure he’s got a writer.” I said, “Tell him he’s a fucking idiot if he doesn’t give me the job.” So he called me up. And I got the job.

It feels like your preoccupation with crime narratives — even though it was there in the early plays, like American Buffalo — really started with the Postman screenplay. Since you work in so many different forms, how did you know this story needed to be a novel?

I don’t know. No idea. I’m basically nuts. I sit by myself every day, most days, eight hours in this little room. It feels like either a torment or an adventure. The only way I can still the torment or appreciate the adventure is to write it down.

The book’s being marketed as if you’ve been planning to write it for 20 years.

I wrote a pretty good Vermont novel [The Village]. Then I spent years working on an L.A. novel. I have over a thousand pages of it that I need to boil down into something that works. The best way to get a writer to create something is to get him to do another thing.

Is the L.A. novel also historical?

No, it’s kind of contemporary. I gave them both to an agent. Earlier agents had said, “No one wants this fucking book.” Ricky Jay, who’s my close friend, suggested this agent [David Vigliano], so I sent both novels in utero, asking him, “What do you think?” He said, “What do you think?” I said, “Fuck, I dunno.” He said, “Write the Chicago novel.” So I did. God willing, this book will get sufficient success that I’ll go on to write the other novel.

What do you view as sufficient success?

It means anything other than “Well, why don’t you curse God and die?”

Okay, that’s fair.

My hero is Patrick O’Brian [author of Master and Commander, among many other novels]. It’s basically impossible to write that well. And I read all of his books many, many times. I’ve read them so many times I can’t read them anymore because eventually you know the whole book by heart.

You’ve mentioned previously that when you were writing the screenplay for Hoffa, Shel Silverstein gave you some advice about research: Never do research. When you do research, all you’re doing is reading books by other people who didn’t do research. Did that apply to this book as well?

I know a little bit about a lot of stuff in the book. You grow up in Chicago and people are talking about gangsters all the time. Here’s where Nails Morton’s horse was shot; there’s the Holy Name Cathedral where they shot Dion O’Banion. I went to school across the street from the garage where they had the Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre. You were always aware of it because it’s all part of the myth. “My uncle knew Al Capone”: Everyone says that.

But how many uncles can really know Capone?

Of course. You know, someone asked me, “If there was anyone in the world you could spend an evening with, who would it be?” I said Pancho Barnes. Do you know who that is?

No.

Oh my God. She was a very wealthy debutante in Pasadena. They married her off to the Reverend Barnes. On their wedding night, he ran screaming from the room, and she said, Fuck this. Took some money out of his clothes, left the Beverly Wilshire hotel, hitchhiked onto a boat, passing as a guy, and went to Mexico. She was a gunrunner. She came back over here and came into her inheritance. She raced speedboats. She became a champion aviator. Then she established a little hotel up at what later became Edwards Air Force Base. Eventually it became a hangout for fighter pilots, then it became a bordello, Happy Bottom Riding Club. She had this fantastic life! Kim Stanley portrayed her in The Right Stuff. I could never meet Pancho Barnes, so I wrote a play about her, a little monologue.

Will it be staged?

Sure, it’ll be staged. I got all sorts of stuff coming up. I might secretly be doing a play on Broadway this summer.

Are you still attached to write a script based on Don Winslow’s The Force?

I wrote it.

Where are things at with it?

I wrote this great script for Jim Mangold. He took it to the producers. They said it was a wonderful script, but would you mind making it a little bit worse? That’s the way the process works out here. I’m trying to walk a thin line between making the studio happy and not disgracing myself in front of God and the world.

You’ve praised Patrick O’Brian, John le Carré —

And don’t forget to mention George V. Higgins.

Right, he’s one of your favorites, too. What other crime writers do you admire?

I’m crazy about the Richard Stark books. You don’t do better than The Hunter. That book changed my life.

How old were you when you read it?

Twelve? I used to spend all day reading. I’d read four books in a day. Why not? Everything in science fiction, all these “Kick ’em in the balls” books. What fun!

Obviously, books influenced not only what you wrote but your worldview.

As my rabbi says, all knowledge is culturally based. You see what the culture is committed to or has trained you to see. That’s the world I grew up in. The mayor was running a whorehouse, people coming day and night, cops on the street. One time, Bill Mauldin, the cartoonist, was outside on the street taking pictures; they beat him halfway to death.

How much of that Chicago is still in the city today?

No idea. I’m going back to do an event for the book, and I’ll see my beloved stepmother. When I grew up, you could see the fires of Gary, Indiana, every night, burning orange. Now the cities are beautified. Chicago is the most beautiful city. But it’s a different city. In 1835, it was one mud hut. Things change.

*This article appears in the February 19, 2018, issue of New York Magazine.